Taipei

Taipei

by Tao Lin

Vintage, June 2013

256 pages / $14.95 Buy from Amazon

Tao Lin is a writer whose novels, short stories, poetry, and essays have won many admirers, and inspired what seems like an equal amount of detractors (it’s a conversation being energetically carried out on the Internet, for the most part). His recent novel, Taipei, is his most publicised book. It’s about a young writer living in Brooklyn who ingests lots of illicit and non-illicit drugs, uses his MacBook to ‘work on things’, goes on a book tour, visits his parents in Taipei, ingests more drugs, and tries to connect with people.

Though I’d come across bits and pieces of Tao Lin’s writing online, my response was emphatic in neither a positive or negative direction, and it would hardly constitute a bias. The thrill, therefore, I got from reading the first sentence of Taipei was pure, and due as much to my having an immediate feeling as it was to the sentence being good. I’ll reproduce it here, for the pleasure of doing it, and possibly to annoy anyone who doesn’t agree with me: It began raining a little from a hazy, cloudless-seeming sky as Paul, 26, and Michelle, 21, walked towards Chelsea to attend a magazine-release party in an art gallery. As far as sentences go, it’s accessible, controlled, and idiomatic. Its tone, too, is consistent throughout the novel – which could pass as one definition of good writing. In regards to Tao Lin, whose prose veers so close to ‘bad writing’ that it sometimes reads like parody of bad writing, it’s an important distinction to make.

I’ve read that Tao Lin completed his bachelor’s degree in Journalism. Although it’s a bad habit to speculate on a writer’s influences, I can’t help but draw a connection between this biographical fact and his third novel. For one, Taipei is an autobiographical account covering 18 months. The novel is, for the most part, chronologically linear, and much of what happens finds its genesis in Paul’s (journalistic?) impulse to self-document. There is the absurd, fake documentary Paul and Erin decide to make about the ‘first’ McDonald’s in Taipei; filming themselves on MDMA and other drugs to post on YouTube; live-tweeting X-Men First Class while on heroin; writing accounts of their first ‘drug fight’ (both Paul and Erin render it in a ‘Raymond Carver-esque manner’, as it happens); Paul emailing himself a bullet-point account of a dinner with Erin parents, etcetera.

What’s most interesting, though, is the manner in which Tao Lin uses as a model journalistic prose. In doing so, he upends certain expectations of artistic and imaginative writing. For instance, there is a pretence to objectivity that characterises much reportage, and it results in writing that is cold and impersonal; this is a quality mimicked in Taipei, whose sentences are often flat and literal. However, while this is what the surface of the prose conveys, what it’s actually presenting is a third-person voice so close (and indistinguishable from Paul) that it is radically subjective. Tao Lin adopts stylistic traits associated with the opposite of ‘literary’ writing; a denotive, sub-literary style becomes prose whose innate quality is not what it seems. The agility and nuance of the syntax can balance multiple clauses, and take the reader off-guard with the most unlikely images.

On the plane, after a cup of coffee, Paul thought of Taipei as a fifth season, or ‘otherworld,’ outside, or in equal contrast with, his increasingly familiar and self-consciously repetitive life in America, where it seemed like the seasons, connecting in right angles, for some misguided reason, had formed a square, sarcastically framing nothing -or been melded, Paul vaguely imagined, about an hour later, facedown on his arms on his dining tray, into a door locker, which a child, after twenty to thirty knocks, no longer expecting an answer, has continued using, in a kind of daze, distracted by the pointlessness of his activity, looking absently elsewhere, unaware when he will abruptly, idly stop.

One specific example of a stylistic signature that Tao Lin has made his own is the noting of the age of any person in Paul’s social life (as in the novel’s opening sentence). I’d say this does at least two significant things. Firstly, as I’ve mentioned, it’s reminiscent of purposely bland, direct reporting; and secondly, it satirises a contemporary social reality. Among creatively ambitious people (and the twenties might be its most intense manifestation) age is tied to notions of precocity and perceived achievement. Socially, these are two things many people want to embody, and which are the cause of much anxiety. As trivial though it may seem, the curiosity surrounding a social rival’s precise age, for many of us, is hard to overcome (often it’s the only thing we want to know).

His style also makes use of what can appear an egregious placement of adjectives. ‘Dancey’ music, or, a ‘vague’ amount of time: these are just two instances of a writer who might seem bored with writing. After all, it’s the sort of silly shorthand we use when we’re being lazy in real life. On the other hand, however, it’s also unsettling close to how many supposedly over-educated people speak, and narrate internally (as Paul is doing). To me it’s funny for its accuracy. And more than just comic effect, it captures the way clever, emotionally-isolated people can use language to distance themselves from their concrete surroundings, other people, and their own feelings. (A similar thing is achieved by the use of stock phrases and cliche, as contained in those now ubiquitous ironizing quotation marks.)

This all being the case, I’m not going to deny there was a point about mid-way through the novel when I put it down with the thought I’d had enough. Some of the long, diffuse sentences seemed unnecessarily confusing: It had seemed like they would never fight, and the nothingness of the future had gained a framework-y somethingness that felt privately exciting, like entering a different family’s house as a small child, or the beginning elaborations of a science-fiction conceit. But when I did put it down, I found the novel’s voice was stuck in my head. There is something about a sentence like the one I’ve just quoted which, to my mind, resembles pre-articulate thought. The spirit of Henry James hovers over the pages of Taipei. A Jamesian sentence does the impossible, it gives an impression of the inchoate process of consciousness, and at the same time, it crystallises multiple thoughts (all in what appears to be a single thought). A Tao Lin sentence makes the journey from inside Paul’s head, onto the paper, untransformed; in other words, it is an underdeveloped version of a Jamesian sentence in which nothing is crystallised. Tao Lin’s portrayal of the inner life is similar to the common experience of thinking like a genius, and when it comes to articulating the thought, speaking like an idiot (I’m misappropriating Nabokov.)

Which brings me to a final comment. It is tempting to read Paul (Tao Lin’s fictional avatar) as intended to be representative of an entire generation (or at least one of its more visible sub-groups – namely, Brooklyn-dwelling literary poseurs). But I don’t think that is the intention. To me, Paul is strange (and maybe even unique); and despite frequent moments of recognition, reading Taipei is not like looking into a mirror. For all its representation of a life lived through the internet, the novel’s aim is a traditional one.

…[Paul] uncertainly thought he’d written books to tell people how to reach him, to describe the particular geography of the area of otherworld in which he’d been secluded.

***

Tim Curtain writes fiction and lives in Melbourne, Australia. His reviews and stories have appeared online and in print.

Taipei

Taipei Great Guns

Great Guns

Videotape

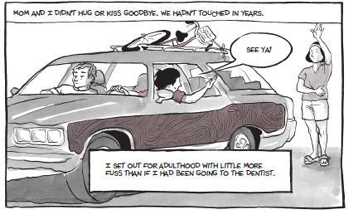

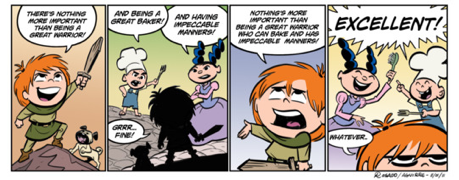

Videotape The Best American Comics 2013

The Best American Comics 2013

The Circle

The Circle