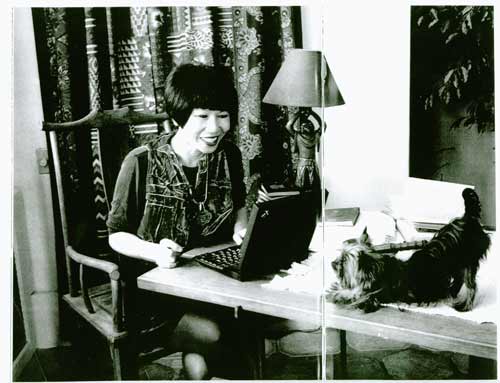

I first came across Joshua Cohen’s work a couple years ago at AWP. I walked by the Starcherone Books table and asked editor Ted Pelton which book he would recommend. He handed me a bunch, and luckily, among those was Cohen’s A Heaven of Others. What struck me then (and continues to strike me every time I read his work) is what an incredible badass he is. For one, he’s an amazing writer. His words are quite literally delicious. But beyond that, he’s the most prolific writer I know (and I know some crazy prolific writers!). Still shy of thirty, he’s got four books in print, one on the way from Dalkey Archive, and tons more sitting either on a physical or virtual shelf. Cohen is a powerhouse, but don’t take my word for it. Go buy one of his books. You won’t regret it.

I first came across Joshua Cohen’s work a couple years ago at AWP. I walked by the Starcherone Books table and asked editor Ted Pelton which book he would recommend. He handed me a bunch, and luckily, among those was Cohen’s A Heaven of Others. What struck me then (and continues to strike me every time I read his work) is what an incredible badass he is. For one, he’s an amazing writer. His words are quite literally delicious. But beyond that, he’s the most prolific writer I know (and I know some crazy prolific writers!). Still shy of thirty, he’s got four books in print, one on the way from Dalkey Archive, and tons more sitting either on a physical or virtual shelf. Cohen is a powerhouse, but don’t take my word for it. Go buy one of his books. You won’t regret it.

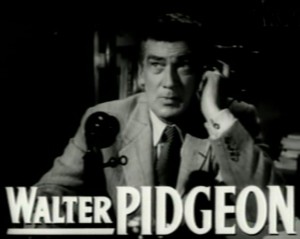

— Lily Hoang

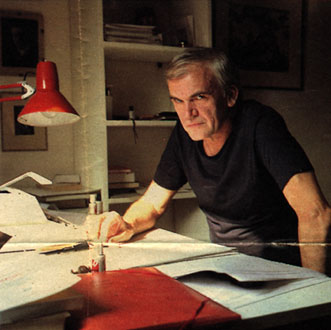

LH: Something that really strikes in about your writing is the very distinctive voice your characters have. In A Heaven of Others (from here on out known as Heaven), the narrator has an extremely urgent voice, one that compelled me to read faster & faster, until I was practically skimming. (Then of course, I had go back and read the whole thing over again to really savor the language!) Cadenza for the Schneidermann Violin Concerto (known as Cadenza), however, has a much more patient narrative voice. Can you tell me more about the development of these narrators in particular? Please feel free to talk about your other works as well.

JC: The voices of both my novels are fictions within fictions, and, as that, they’re opposites: The voice of A Heaven of Others is that of 10-year-old Jonathan Schwarzstein of Tchernichovsky Street, Jerusalem. The voice of Cadenza for the Schneidermann Violin Concerto is that of Laster, an octogenarian, perhaps nonagenarian, concert violinist from eastern Austro-Hungary. Again, both are fictions, meaning both are ultimately Me. I think what I’ve done in all my books so far comes, primarily, from speech rhythm. The rhythm of how I want to speak. How I speak to myself. As for echoes, A Heaven of Others derives from poetry, especially 20th century Hebrew poetry (Dan Pagis), and German-Jewish poetry (Paul Celan), while Cadenza comes from comedy, and despite its typographical trickery owes more to the history of the novel, and much, specifically, to Saul Bellow.

READ MORE >

I first came across Joshua Cohen’s work a couple years ago at AWP. I walked by the

I first came across Joshua Cohen’s work a couple years ago at AWP. I walked by the