Reading what’s extraneous

Last week at Big Other, Paul Kincaid put up a brief but intriguing post in which he asks to what extent various factors surrounding a text influence the way we think about it or its author. He gives the following example:

The program I use for databasing my library pulls down information from a wide variety of sources ranging from the British Library and the Library of Congress to Amazon. More often than not, this can produce some very strange results. I have, for instance, seen novels by Iain Banks categorized as ‘Food and Health’, and novels by Ursula K. Le Guin categorized as ‘Business’. In all probability, these are just slips by somebody bored, though you do wonder what it was about the books per se that led to such curious mistakes.

Paul’s musings raise many interesting questions. For one thing, we might wonder whether the factors he’s describing are indeed extraneous or external to texts. Because I can imagine a good post-structuralist immediately objecting that texts more porous than that, and that it’s all just a sea of endless texts slipping fluidly into one another.

Me, I don’t have a problem with treating texts as discrete and coherent entities, but I admit the situation is complicated.

A bit more on Susan Sontag and “Against Interpretation”

I’m still bogged down with school (almost done) but I thought I’d throw a little something up, pun intended. Two months ago I wrote an analysis of Susan Sontag’s “Against Interpretation” where I argued that, rather than being opposed to all interpretation, as some believe, Sontag was instead opposed to “metaphorical interpretation”—to critics who interpret artworks metaphorically or allegorically. (“When the artist did X, she really meant Y.”) I thought I’d document a few recent examples of this—not to pick on any particular critics, mind you, but rather to foster some discussion of what this criticism looks like and why critics do it (because critics seem to love doing it).

The first example comes from Chicago’s Museum of Contemporary Art, in particular the exhibit “Destroy the Picture: Painting the Void, 1949–1962” (which is up until 2 June). One of the works on display is Gérard Deschamps’s Tôle irisée de réacteur d’avion (pictured above, image taken from here—I didn’t just stretch out a swath of tinfoil on my apartment floor). The placard next to it reads as follows:

Experimental fiction as genre and as principle

A few years ago at Big Other I wrote a post entitled “Experimental Art as Genre and as Principle.” That distinction has been on my mind as of late, so I thought I’d revisit the argument. My basic argument then and now was that I see two different ways in which experimental art is commonly defined.

By principle I mean that the artist is committed to making art that’s different from what other artists are making—so much so that others often don’t even believe that it is art. As contemporary examples I’m fond of citing Tao Lin and Kenneth Goldsmith because I still hear people complaining that those two men aren’t real artists—that they’re somehow pulling a fast one on all their fans. (Someday I’ll explore this idea. How exactly does one perform a con via art? Perhaps it really is possible. Until then, I’ll propose that one indication of experimental art is that others disregard it as a hoax.) Tao visited my school one month ago, and after his presentation some folks there expressed concern, their brows deeply furrowed, that he was a Legitimate Artist—so this does still happen. (For evidence of Goldsmith’s supposed fakery, keep reading.)

Eventually, I bet, the doubts regarding Lin and Goldsmith will fall by the wayside. Things change. And it’s precisely because things change that the principle of experimentation must keep moving. The avant-garde, if there is one, must stay avant.

That’s only one way of looking at it, however. Experimental art becomes genre when particular experimental techniques become canonical and widely disseminated and practiced. The experimental filmmaker Stan Brakhage, during the 1960s, affixed blades of grass and moth wings to film emulsion, and scratched the emulsion, and painted on it, then printed and projected the results. Here is one example and here is another example. And here is a third; his films are beautiful and I love them. (The image atop left hails from Mothlight.) Today, countless film students also love Brakhage’s work, and use the methods he popularized to make projects that they send off to experimental film festivals. (Or at least they did this during the 90s, when I attended such festivals; I may be out of touch.)

Those films, I’d argue, while potentially beautiful and interesting, are not necessarily experimental films. As far as the principle of experimentation goes, those students had might as well be imitating Hitchcock.

The difference between a concept & a constraint, part 2: What is a constraint?

OK, back to this. In Part 1, I traced out how in conceptual art, the concept lies outside whatever artwork is produced—how, strictly speaking, the concept itself is the artwork, and whatever thingamabob the artist then uses the concept to go on to make (if anything) counts more as a record or a product of the originating concept. (This is according to the teachings of Sol LeWitt, as practiced by Kenneth Goldsmith.) Thus, we arrived at the following formulation:

- Artist > Concept > Artwork (Record)

Now, I’m not going to argue that every conceptual artist on Planet Earth works according to this model. But LeWitt’s prescription has proven influential, and continues to be revolutionary—because choosing to work with either a concept or a constraint will lead an artist down one of two very different paths. To see how this is the case, let’s try defining what a constraint is, aided by the Puzzle Master himself, Georges Perec . . .

The difference between a concept & a constraint, part 1: What is a concept?

Sol LeWitt: “Wall Drawing #1111: A Circle with Broken Bands of Color” (2003, detail). Photo by Jason Stec.

[Update: Part 2 is here.]

I wrote about this to some extent here, but I wanted to expound on the issue in what I hope is a more coherent form. Because I frequently see concepts confused with constraints, and the Oulipo lumped in with conceptual writing. For instance, this entry at Poets.org, “A Brief Guide to Conceptual Poetry,” states:

One direct predecessor of contemporary conceptual writing is Oulipo (l’Ouvroir de Littérature Potentielle), a writers’ group interested in experimenting with different forms of literary constraint, represented by writers like Italo Calvino, Georges Perec, and Raymound Queneau. One example of an Oulipean constraint is the N + 7 procedure, in which each word in an original text is replaced with the word which appears seven entries below it in a dictionary. Other key influences cited include John Cage’s and Jackson Mac Low’s chance operations, as well as the Brazilian concrete poetry movement.

I would argue that the Oulipo, historically speaking, are not conceptual writers/artists—although it’s easy to see how that confusion has come about, because the Oulipians have proposed some conceptual techniques, such as N+7 (which I’d argue is not a constraint). (Also, it’s each noun that gets replaced, not each word.)

What, then, distinguishes concepts from constraints? And why does that distinction matter? In this series of posts, I’ll try answering those questions, starting with what we mean when we call art conceptual.

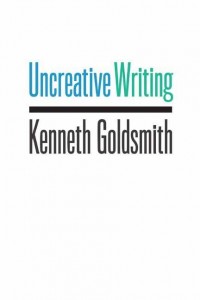

25 Points: Uncreative Writing

Uncreative Writing

Uncreative Writing

by Kenneth Goldsmith

Columbia University Press, 2011

272 pages / $23.95 buy from Columbia UP

1. Uncreative writing is situating. A détournement. A patchwriting. Goldsmith: “context is the new content.”

2. A portrait of Stéphane Mallarmé with “A Throw of the Dice” inserted three times:

3. Uncreative writing is language as pure material. Quantity over quality. The digital-age inheritor of Stein, Concrete Poetry, Mallarmé, Herbert, Apollinaire, and L=A=N=G=U=A=G=E. It sees the internet as language abundant, language swim, all text thrum. Goldsmith: “What we take to be graphics, sounds, and motion in our screen world is merely a thin skin under which resides miles and miles of language.”

4. Much of what Goldsmith says uncreative writing is is stuff I already know. Through Flarf, through FC2 and Les Figues Press, through Goldsmith’s own work like Day or Traffic or Sports, through Walter Benjamin and Gertrude Stein and Vanessa Place, through this blog, through Ron Silliman’s blog, through David Markson, through any number of conceptual writers working today.

If you’re familiar with these things too, you’ll nod your head and move along through a number of the early essays here. If you’re not familiar with these things, this book’s a solid place to begin.

5. But I’m not sure Goldsmith thinks he’s saying anything radically new with these essays as much as he’s articulating (again) a stance toward language that should be obvious to anyone writing, but still, for some reason, isn’t.

A sense of perplexity—maybe even frustration—about a large segment of contemporary writing runs through the early essays here.

Goldsmith wonders: What happened that made most 20th and 21st-century writers miss the work of Duchamp, LeWitt, and Warhol? Why did conceptualism take off so readily in the visual arts and not in the literary? What is taking writing so long to mine the possibilities of the conceptual text? What’s with all the holdover from literary Romanticism? The stuff about genius? The stuff about ego and originality? All that stuff about having a voice?

Still worthwhile questions.

6. Here’s Goldsmith’s annotated copy of Charles Bernstein’s “Lift Off,” a piece of uncreative writing Bernstein built by transcribing the characters from the correction tape of his manual typewriter.

Here’s a recording of Goldsmith performing it.

I like this poem because it’s hard to see it being made today. I like this poem because of its impossibility.

And I like Goldsmith’s performance of it because, even with all that, he shows how the thing’s still legible.

7. When’s the last time you typed another writer’s story word for word?

8. Picasso’s Portrait of Gertrude Stein with excerpts from The Making of Americans inserted: READ MORE >

February 5th, 2013 / 12:09 pm

An Evening of Poetry at the White House

If you’re wondering what Kenneth Goldsmith ended up doing when he read at the White House, here’s the video (he’s at 8:55).

The 100th (!!!) issue of Mike Topp’s Stuyvesant Bee came out this weekend. Receiving the weird little pages in my email every week is a sustained thrill, and SB has an intensely lazy awkward traumatic aura that still somehow is funny. It hurts comedy, part by part. The always-ON Joyelle McSweeney wrote this essay about Dogtooth. She got all the right words out and together about this excellent movie. And Kenneth Goldsmith is rewriting The Arcades Project, setting it in 20th century NYC and calling it Capital, with his full overview here. Then: Goldman Sachs continues to ruin! This time: food.

I Like What The Hell Is Going On Over Here And Send Me Some Stuff

Open letter from Kenneth Goldsmith on UbuWeb about UbuWeb and why the wrong way is the right way to run a file archive of unprofitable products.

Fall is because Spring is colder than winter.

Forgot to say something about Thirty days as a Cuban in Harper’s. In to it. If you’re not a subscriber, go to the library or steal it from your doctor’s office. If they ask you why you’re hanging around the lobby, tell them you’re just making sure they’re here for you.

Taking submissions for hahaclever, including and especially ebooks ~10,000 words (like the highlander, there can be only one, what I’m saying is please try to be the highlander). Rebuilding the website, new comics editor coming on board, maybe a text editor, might have a board to come on, shit like that going on. If you’ve sent something in the past and haven’t heard from me, we’re sorry. They will get back to you soon.

At Titular, we could use a Halloween piece because I like when people send holiday pieces like Christmas’s Cocoon by Amber Sparks.

The Cardini Brothers’ Catch-Up has a new website for to look at with your eyes and a new print issue for to buy with your fingertips. The print issue is slick. It’s all comics and poems done in fun and done in love with making and thinking on the future and being ready for it to be happening or to be made to happen. This is a thing they did to promote the last, first issue. READ MORE >