Reading Matthew Stokoe’s High Life

I finished reading Matthew Stokoe’s High Life

I finished reading Matthew Stokoe’s High Life (Little House on the Bowery, 2002) last night, after spending the past three or four days with it. I read it in bed, in the bathtub, on both the couch and the big chair in our living room, on the beach at St. George Island, and in my car sitting at various locations in Tallahassee. It put me through an experience, which I consider proof of artistic excellence. But beware, excessive brutality of sex and violence permeates this text. Prepare to be unsettled…

To remember this idea after waking: An Interview with Christopher DeWeese

Recently released from Octopus Books, Christopher DeWeese’s The Black Forest is a slim, refreshing volume, intent on bending time and expectation in language carefully measured, calm and clear. It was described by James Tate as such: “These poems sock home truth and enact poetic somersaults that leave me out of breath. It’s a pleasure to recommend them to anyone brave enough. Chris DeWeese is the real thing, a poet true to his calling.”

BB: The Black Forest is your first book, while also one of many you have written over the years in coming up to it. Did you know this book was a specific project when you began the poems in it, or how did it come together as what it is?

CD: For three years while I was getting my MFA I only worked on this one thing, a sequence of poems called The Confessions. When I started that project, I had just been blown absolutely away by Berryman’s The Dream Songs and Berrigan’s The Sonnets, and I had this feeling that maybe writing a book-length poem was the solution to all of my problems. I remember at the time being very confused about how to write poems: before grad school, I had been writing pretty much on my own for a few years, and the poems I wrote were not very good, and all of a sudden I was around all of these people who seemed to already have really confident, singular styles, and I felt like I didn’t know what I was doing or (more importantly) even what I wanted to do in writing poetry.

The most helpful thing about just writing this one project for so long was that it gave me a stable architecture of form to write into. And that was huge for me, because I felt like just starting to write an individual poem was a process weighted down with huge decisions, decisions about form and content that needed to have complicated rationales lurking behind them. So for three years, I didn’t have to worry about that, because I was totally committed to just working on this one thing. And by the time I finished working on it, I was ready to realize that the way I had thought about the process of making poems before was actually totally wrong (for me at least) and that one good and valid way of composing poetry is to just start writing and to see what happens. So when I started writing the poems that would eventually compose The Black Forest, there were no ideas about the poems going together or belonging together as a certain project: there was just this feeling of freedom, and a desire to be loose and wild with my imagination. I had just started running when I began to write these poems, and a lot of the first lines would occur to me while running, and then I would spend the rest of the run saying the line over and over to myself to try and remember it, and by the time I got home the line would have achieved this power, this importance borne of repetition, so I’d write it down and often the rest of the poem would come out very quickly. And over time, I did realize that a lot of the poems I was writing belonged together, that they shared a lot of language and concerns, and it felt good to realize that the consistency of the book had come together in a fairly organic way. READ MORE >

Let’s talk about James Merrill

James Merrill died in Tucson. Tucson is a city where men walk around with Rottweilers and wheelbarrows. Sometimes inside the wheelbarrow will rest a console television. These men do not wear shirts.

Some writers were afraid of James Merrill. It’s like that time Dick Cavett interviewed Marlon Brando. (Go to 5:45 for some inspiring tension) Cavett was shaking. He was addled and rattled. He was overwhelmed by the Hugeness of this Thing, Brando.

Factoid: People think Calvin Cordozar Broadus, Jr. is all that, but James Merrill was the first to sing, “Come dusk lime juice and gin.”

Remember to remember!

James Merrill’s most famous quote is obviously, “Life is fiction in disguise.” I’m trying to decide if John Gardner would approve. Oh, fuck Gardner, man. I just realized Hemingway is always talking about how he doesn’t like to talk about writing, and even saying that is talking about writing and anyway Hemingway actually wrote and talked about writing all of the time. But I digress. Better quotes from Merrill would be, “I’ve watered the geraniums, the pot of basil + the pot of pot” or “If nobody ever wrote a book, do you imagine it would be possible to catch up?”

Or

Then I addressed to a closed door a little speech about how the Great Ideas, far from being the achievement of men of genius (or look what happens when they are—Nietzsche + Hitler, Einstein + Hiroshima), are the work of thousands of anonymous generations, and take the form of those brain-coral reefs, slow myths + taboos, which keep the shark from the shallows our children swim in, and now if you don’t mind I have taken a pill and must try to get some sleep.

One time James Merrill made a concrete poem in the shape of a Christmas tree. I find concrete poetry as sort of airbrush T-shirt level of entertainment.

Champagne. Mythology. Technical mastery. Memory. Atomic science. The big bang and black holes. Quatrains. Environmental degradation. Key West. AIDS. Neckties. Similes. Flashlights. Elizabeth Bishop. Small mirrors. The Piano. Good outdoor lighting (example, Peru). Waving through windows at people. O’Keeffe paintings. Dogs. A well-considered title.

I don’t like titles that applaud the author’s seriousness or whatever, titles like “Necessities of Life” or even, forgive me, “Responsibilities.”

Many lovers.

Sometimes, while rereading Changing Light at Sandover, the irony keeps me at a distance, but then again it might just be something I ate.

Factoid: You can say what you want about Dick Cavett, but in 1969 Jefferson Airplane sang on his show and it was the first time the word “fuck” was uttered on live television.

We’re going to spend a lot of our life alone in rooms.

A Pan-English Dictionary (for readers of Harry Mathews’s The Sinking of the Odradek Stadium)

And while on the subject of reposting literary resources: here’s a Pan-English dictionary I made for the benefit of anyone reading Harry Mathews‘s early masterpiece, the epistolary novel The Sinking of the Odradek Stadium.

And while on the subject of reposting literary resources: here’s a Pan-English dictionary I made for the benefit of anyone reading Harry Mathews‘s early masterpiece, the epistolary novel The Sinking of the Odradek Stadium.

Odradek presents the correspondence of newlyweds and amateur sleuths Zachary McCaltex and Twang Panattapam. Separated by the Atlantic, they exchange letters in which they “try to trace the whereabouts of a treasure supposedly lost off the coast of Florida in the sixteenth century, while navigating a relationship separated by an ocean as well as their different cultures.”

Twang, who hails “from the Southeast-Asian country of Pan-Nam,” peppers her letters with snatches of her native language, “Pan.” Fortunately for her husband and the reader, she also translates it on the spot. I’ve collected all of the Pan and its English equivalents and presented them below.

The Weaklings Library

An impressive compilation of Books Dennis Cooper Loved appears at The Weaklings Library.

Now available for pre-order from the always-exciting Jaded Ibis Press, NO ONE TOLD ME I WAS GOING TO DISAPPEAR, “a novel told in thick chunks of language and explosions of lines and colors” by J.A. Tyler & John Dermot Woods. Order soon to receive a limited edition print that’s sure to be gorgeous.

Here’s a nice interview with the authors about the making of the book.

And here are good words from the Los Angeles Review, including this sentence, which has me sold: “Only the barest of plots is visible, yet the story’s climax is as powerful as that of the most meticulously planned novel.”

In Real Life

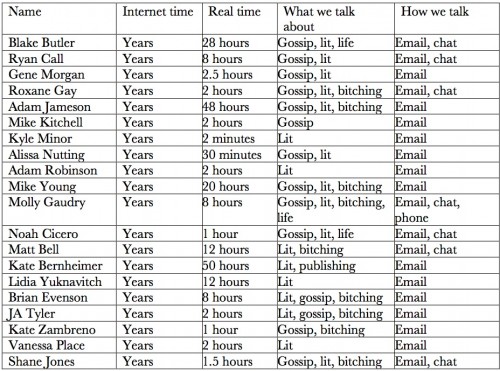

Last week, Blake was in town to give a reading. The first iteration of my intro for him detailed our friendship, how virtual it is, and all this hoop-la reminds me – again – of the fucked up nature of the intersection of our virtual writer-avatar selves v. real personhood. Most of the writers I have relationships with, I barely know. Most of the writers I know, I’ve spent less than a day with in real life. Most of the writers I have friendships with, we met online, interact online, and I know very very little about who they are, what they do everyday, what they care about aside from what they post online. We may interact regularly – daily, weekly, whatever – but they’re still not real, not until we meet face to face, and still, it’s within the artificial space of a conference or a reading, so it’s not really real. And yet, they must be real people with real cares. I know almost nothing about them.

Okay, so Derrick Rose will maybe never again play basketball like such a firefly, but that doesn’t mean you should stop believing in the triumph of the canny and soulful: for example, friend of the GIANT Heather Christle has won The Believer‘s 2011 Poetry Award for her book The Trees The Trees. Congratulations, Heather!

anonymous contribution to the ‘subgenre’ of ‘literary’ ‘essay’ known as ‘how i feel about marie calloway’

Reading Noah Cicero’s piece about Marie Calloway, it struck me that the Internet has invented a subgenre of literary essay. These essays could be easily be published in a volume called ‘How I Feel About Marie Calloway,’ collecting the torrents of writing about ‘Adrien Brody’ alongside the very small trickle of responses to ‘Jeremy Lin.’ Someone should publish this, if for no other reason than that we might see the collective bloviation of our Best Minds on a topic that eludes them completely. Tao Lin might have done, if ‘Jeremy Lin’ hadn’t so effectively outed him.

Before I get into any kind of Substantial Critique, I’d like to point out that we are discussing a young woman of twenty-two years. She’s not a symbol, she’s not a literary persona, she is an actual human being of twenty-two years. I remember when I was twenty-two years old. I could barely tie my shoes and had a problem with public drooling. Calloway is also, it must be said, a young looking twenty-two. Both by genetics and by design, she appears about sixteen years old.

The Marie Calloway Problem is pretty simply stated: we live in a society in which the mechanisms of commerce are designed to encourage us to believe that young women are randy hot sex machines, but we have a collective meltdown when one of them actually writes about sex that is anything other than vanilla. It breaks discourse. We’re that unevolved.

This was, in part, the pro-Calloway critique offered by many women writers in the days after ‘Adrien Brody’ went viral. The problem with such critiques is that almost all of them attempted to tie Calloway into a greater narrative. ‘Adrien Brody’ could not exist in a vacuum. It needed to be contextualized within its Greater Import.

This is nonsense. ‘Adrien Brody’ is a piece about a groady balding Brooklyn Intellectual who writes about Big Issues (Why is Capitalism Bad?) having sex with a twenty-one year old woman that likes his Twitter. The woman, recounting the tale, makes vague allusions to Marx, Marxism and Marxist thinkers. The Marxism is, of course, an affect.

May 1st, 2012 / 2:54 am