Nervous Device by Catherine Wagner

Nervous Device

Nervous Device

by Catherine Wagner

City Lights Publishers, October 2012

City Lights Spotlight Series No. 8

73 pages / $13.95 Buy from City Lights or SPD

I’ve had a copy of Catherine Wagner’s latest collection, Nervous Device, for three days and already it’s beat up, pages are folded and scribbled over, and the whole book is bent in half (the result of a heavy bashing I gave it against the side of my desk). Many of my most-loved books end up looking similarly destroyed, but the physical damage I’ve done to Nervous Device stems from a different impulse—what I can only call frustration.

So why am I frustrated with this unassuming, 73-page collection, particularly since I’ve been a Wagner fan since her first book, Miss America, came out in 2001? It’s because I don’t know how to find coherence in this collection and yet—here’s the frustration—I can’t stop reading it.

When I begin a new book of poetry I don’t look for cohesion of any particular kind, nor do I think all collections need to, or benefit from, coherence. However, in reading Nervous Device I felt that I was missing some critical structure that created a through-line in the book. I kept asking, why these poems? How is this a collection?

Then I realized maybe that was the point—Wagner isn’t interested in packaging the poems for us—we must do this ourselves. In an interview with Elizabeth Coleman at Art Animal (September 2012), Wagner speaks of her own concern with these poems, saying “‘I worry that in this book I’ve tried to be smart in some places because publishing with City Lights felt like a big deal…That’s a deadly thing—the wish to appear smart’” [full interview here]. I immediately stopped reading the interview, re-read Nervous Device, and realized I was trying to force a larger structure on the book when what I needed to be doing was enjoying it because of its language, poem by poem.

November 26th, 2012 / 12:00 pm

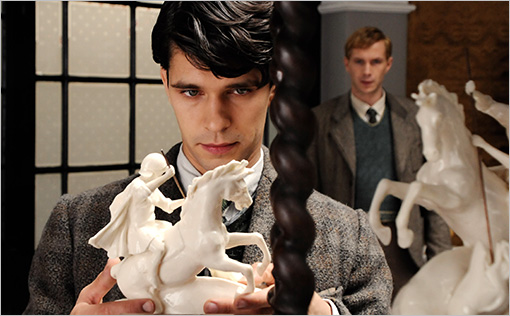

25 Points: Cloud Atlas

1. Dear God did I want to like this.

2. I’m something of a fan of the Wachowskis. Bound and Speed Racer are fun, and I adore the Matrix Trilogy (yes, even the sequels). And I have nothing against Tom Tykwer, either. I enjoyed Run, Lola, Run, and admired his stab at making a Kieslowski (Heaven). I wish there were more filmmakers out there like the three of them.

3. Cloud Atlas is pretty well-directed. It presents six different plots across six different timelines, and (speaking for myself) it was easy to follow, narratively. That’s not nothing.

4. I’ve long argued that Titanic is a very well-made film. It’s three hours long, with dozens of characters, and it never becomes confusing, never drags.

5. This will not be the first time I compare Cloud Atlas with Titanic.

November 26th, 2012 / 8:01 am

Sunday Service: Alex Dimitrov Poem

I Wanted To Write It For You

Someone has written it lightly in dark paint.

Did you come here to be with yourself?

Did you finish that day you couldn’t begin?

That’s not what was written but what I came to ask.

I wanted to live with you.

I wanted to know where you leave yourself

and who you live inside.

Someone has written it lightly in dark paint.

I wanted to call you, I wanted to hear

just you. Talking. To me.

I wanted to see your mouth move.

I wanted to write you.

A novel, no letter.

Do you understand?

I wanted to write

without a beginning or end.

I wanted to write just the love part for you.

Someone has written it lightly in dark paint.

Above a window. Near a fire escape.

Because we have no escape

I wanted to write it.

Someone has written it lightly in dark paint

like I wanted to write it for you.

Just the love part.

That’s the only thing I wanted to write.

That’s what it says. Above a window.

Framed by a fire escape.

That’s what someone has written.

Just the love part.

There’s no plot. Nothing happens.

Nothing will happen in this poem.

Nothing much happens in life.

Nothing worth knowing about really.

Just the love part.

No beginning or end.

I wanted to write it for you.

Alex Dimitrov’s first book of poems, Begging for It, will be published by Four Way Books in March 2013. He is the founder of Wilde Boys, a queer poetry salon in New York City. Dimitrov’s poems have been published in The Yale Review, The Kenyon Review, Slate, Poetry Daily, Tin House, Boston Review, and the American Poetry Review, which awarded him the Stanley Kunitz Prize in 2011. He is also the author of American Boys, an e-chapbook published by Floating Wolf Quarterly in 2012. Dimitrov works at the Academy of American Poets, teaches creative writing at Rutgers University, and frequently writes for Poets & Writers.

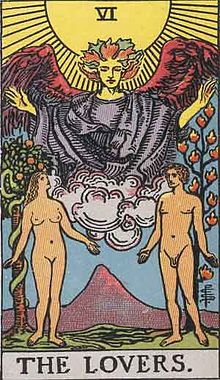

I Wanted To Write It For You was inspired by The Lovers card of the tarot deck.

(Charles)Book&Record – Tradition

Author/editor Zack Wentz (The Garbageman and the Prostitute, newdeadfamilies.com) has teamed up with Taj Easton and Shelby Gubba to create a new multi-media project called (Charles)Book&Record. “Tradition” is the third video in a triptych, part of what they call “sci-fi-surrealist-soul.” The first video, “Pointing South,” premiered at Juxtapoz, and the second, “Sentimental Ape,” at Geek.

Their debut album, Leftover Magic, was recorded and mastered at Singing Serpent studios in San Diego, CA., and will be released digitally by the band in January, 2013.

Remixes are forthcoming from Rafter, Xiu Xiu, and FUNERALS, as well as a serialized movie, related to the band/album, entitled Bad Dreamer. Taj Easton and Zack Wentz were also commissioned to create a soundtrack for the short Andy Mingo film Romance, based on a short story by Chuck Palahniuk (Fight Club), which debuted in London at the Raindance Film Festival in the fall of 2012.

Living to tell the tale

Joseph Anton: A Memoir

Joseph Anton: A Memoir

by Salman Rushdie

Random House, September 2012

656 pages / $18 Buy from Amazon

On the cover of this utterly compelling book, two names belonging to five different individuals introduce the reader to a life abruptly interrupted by politics. First is that of the British author, Salman Rushdie, who deserves praise for the beautiful prose that follows. His surname was adapted by his father from Ibn Rushd, the twelfth century Muslim philosopher whose vein of Islamic scholarship had left its mark on the Rushdie family. Below Rushdie, “Joseph Anton”, a name unknown to history, is inscribed in large letters. This is an invented name which, when taken as a whole, is fictitious, but when separated into two parts, becomes a composite of the first names of Joseph Conrad and Anton Chekov, two of Rushdie’s favorite authors.

Although Joseph Anton is a name invented by the author, the relationship between them is quite different from, say, Oliver Twist and Dickens. The invention here had not been the result of an artistic choice. It was necessitated when Rushdie wrote a novel, in 1989, about the origins of Islam, earning the hatred of Ayatollah Ruhollah Khomeini, the Supreme Leader of Iran.

Khomeini accused Rushdie of blasphemy and issued a fatwa to all Muslims, informing them that the writer of The Satanic Verses as well as “all those involved in its publication who were aware of its content” were sentenced to death. The death of the author, however, had been a wish that was not granted. Rushdie survived and is here to tell the tale. (Others, though, were not as lucky: the Japanese translator of the book was murdered in 1991, the Italian translator was stabbed and his Norwegian publisher attacked at his house.)

Rushdie’s account begins when a BBC reporter calls him to ask how it feels “to know that you have just been sentenced to death by Ayatollah Khomeini?” It doesn’t feel good, he replies before rushing downstairs to lock the front door of his London apartment.

As the reader walks in his shoes in the course of more than 650 densely-written pages, it becomes apparent that Rushdie’s mental state was much more complicated than his initial reaction might suggest. Fatwa becomes for him an elixir, helping Rushdie to identify his friends and his foes. The event also kickstarts a public discussion on blasphemy, religious intolerance and freedom of expression, leading to numerous political stances some of which were taken at the expense of personal safety.

November 23rd, 2012 / 12:00 pm

Noah Falck’s Snowmen Losing Weight

Snowmen Losing Weight

Snowmen Losing Weight

by Noah Falck

BatCat Press, 2012

61 pages / $30 Buy from BatCat Press

Not everybody notices you change. Most of the people, they say hey and start telling you about the bicyclist they killed on the way to work or the pistachio jelly bean they invented in their nap. It takes a special kind of person to point out your haircut. Your weight loss, your new fannypack, your sacrifice flys, your hiccups, the stains on your coat from a watermelon and peanut butter sandwich. And beyond that, it’s a rare bird who will say the soft thing about what they notice. Or will take you as you are into a noticing beyond you both.

Noah Falck’s debut poetry collection, Snowmen Losing Weight, comes with puffy eyes and melancholy jokes, but its realest strength is in its pointer finger. Which is pointed not out of judgment or self-congratulation or even to cocoon two observers against the rest of the cold world (OK, well, more on that later), but to be on the lookout, most always, for a wider circle. Measuring tape that goes forever and is always restarting. Or like it says in the very first poem: “Suppose the wind falls / in love with the wrong / season.” A goal of reckless inclusion, including until we’re out of breath, toward a large and dissolving inhabitance.

First, though: I’m not the world’s waxiest book object dude, but yeah, the physicality of this book is too immediate and elegant not to begin with. Snowmen Losing Weight is four-books-in-one, sectioned out in a double-burger dos-à-dos style. Don’t take my word for it:

I don’t want to compete with a video’s description prowess, but I do want to add two things. One, there’s a real formica nostalgia to the vinyl exterior, like I’m six and trying to find everything I dropped under all the kitchen tables I’ve ever seen. Which is further confirmed by the white-and-black speckling on the cover (inverted on the endpages), which I’m going to go ahead and admit reminds me of cookies and cream ice cream. That was the second thing. The important thing: mad props to the students of Lincoln Park Performing Arts Charter School in Midland, PA, who design and produce BatCat’s books. They’ve done something beautiful and memorable. It’s an expensive book, but that’s because you’ll want to put it where everyone can see it and coo.

November 23rd, 2012 / 12:00 pm

Pig

This is a pig.

It cannot be caught by an eagle, only a raven or a falcon.

The sound that it makes is “hut hut hut.”

Hmph

The moon is bright in this part of Massachusetts.

There is pie downstairs but nobody is eating it.

I was very drunk at one point. Now I don’t know.

People kept talking about money.

I can’t tell how much conversation about things I incited or what I might have said.

People kept talking about politics.

Everything seems fat and watery. I was in my dad’s shed in the backyard.

The Lions really fucked up, but it will have an asterisk if you think about it.

There’s always more to drink in the garage.

I walked to the high school and kicked four field goals. Some coaches came out of the locker room and looked at me. I looked at them and missed badly.

In the bed in my childhood room this morning I read the “Nausicaa” chapter.

I can’t tell if anyone fell asleep or got sick.

I downloaded five CDs of guitar music.

This isn’t what I planned to do while I was sitting on the toilet a few minutes ago.

Some people were walking around the track then drove home.

The pavement looks white from over here.

I remember I thought this morning I smelled.

Cow

While I was traveling on the train the other day, I suddenly stood up, happy on my own two feet, and began to wave my hands with joy and invite everyone to look at the scenery and see the twilight that was really glorious. The women, the children, and some gentlemen who interrupted their conversation all looked at me in surprise and laughed; when I quietly sat down again, there was no way for them to know what I had just seen at the side of the road: a dead, a really dead cow moving past slowly with no one to bury her or edit her complete works or deliver a deeply felt and moving speech about how good she had been and all the streams of foaming milk she had given so that life in general and the train in particular could keep on going.

-Augusto Monterroso