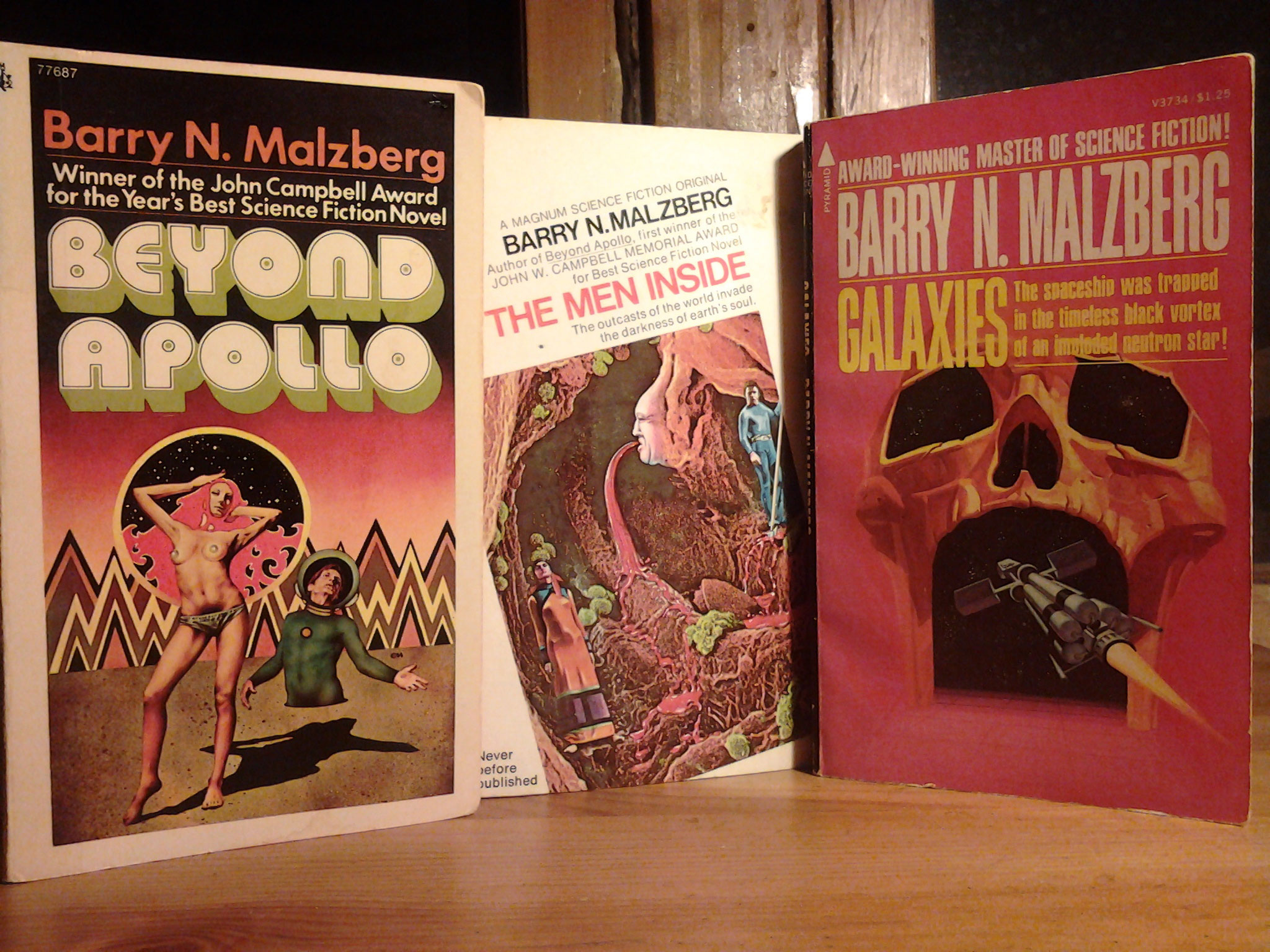

25 Points: Mad Girl’s Love Song

Mad Girl’s Love Song

Mad Girl’s Love Song

by Andrew Wilson

Scribner, 2013

369 pages / $30 buy from Amazon

1. After reading the Bell Jar and the biographical note in the back, the next piece of information about Sylvia Plath that I encountered was the only point of reference I had about her for a very long time. Alice Miller’s For Your Own Good features an essay called “Sylvia Plath: an Example of Forbidden Suffering,” in which Miller illustrates a scene of young Plath presenting to her mother and grandmother a pastel piece on which she has worked hard. The ebullience she demonstrates in showing off her achievement made a searing impression on me—I was not used to seeing female artists proud of their work; I was used to seeing them compromised and unfulfilled. The conclusion of the scene is equally powerful and so devastating, it remains my primary reference point regarding Plath as a depressed person: when her grandmother stood up, she smudged the pastel enough to ruin it. Plath’s flat affect, her inability to situate her disappointment where it belonged, has never not occurred to me when I’ve read about her, even though this scene does not recur with the canonical relish of, like, the St. Botolph’s Review launch party. By virtue of this scene’s inclusion in Andrew Wilson’s Mad Girl’s Love Song, I was swayed at first.

2. Plath’s writing is very important to me, and I love biographies where she is treated as the inexhaustible writer she was. As a subject, though, the way her work is so visceral, so loaded with the feelings that connect her to contemporary readers, that access overwhelming emotion, when she was remote, blank, totally affected: that I find riveting. Death notwithstanding, the more accessible her work, the less accessible she was. One cannot experience the closeness with her as a subject that one feels through her writing.

3. Although I bought and read the book because it’s about Plath, I am reluctant to use the biography as a means to discuss her because her work is more interesting than she is, so there’s that shame: why not talk about the work? In Wilson’s case, I do agree that the events of her young life are unfairly glossed over when she was so productive and disciplined so early, and for that I was excited to read Mad Girl’s Love Song.

4. The people in proximity to Plath aren’t ghosts here, either. Wilson talked to people who remembered her petulantly in some cases and fondly in others, and all vignettes get a greater sense of who they were than who she was, which makes for a livelier telling than what occurs from corralling facts from her archives—how real personalities generally unmoved by her achievements react to the young, raw person who remains animated in their pasts.

5. Her sexual voracity is emphasized as soon as possible, and much dwelled on are the rape fantasies she confessed to correspondent Eddie Cohen. The sole editorialization by the Wilson surrounding these incidents—which occur throughout the book—is: “We have to remember that Sylvia was a young woman overloaded with a huge store of sexual energy that she was not allowed to express…” This is pretty remarkable considering how Wilson handles other events.

6. Besides the unprecedentedly thorough examination of Plath’s childhood and Smith College years, the big news of this biography is how she demonstrated the tendency to self-harm in the immediate aftermath of her father’s death, and that self-harm manifested in the deliberately extreme and suicidal manner of attacks on the throat. This new fact, central to Mad Girl’s Love Song’s purpose, was the point at which I started to feel like I was reading Us Weekly not in terms of content but in terms of how I felt like, why am I reading this, I am so full of shame.

7. An aside: in Twin Peaks: Fire Walk With Me, Laura Palmer knows she’s about to die. Agent Cooper points out how, while she did not commit suicide, she did consent to and prepare for her murder. In her last days, she warned her best friend, Donna, not to wear her stuff: don’t fetishize me, she was saying, don’t make me into a symbol or a set of aspirations, don’t channel me as a transcendent measure to get free from your boring suburban life; I am a broken person and I am in so much pain. It’s an incredible privilege that the dead girl gets – the audience is not only used to her as a structuring absence, but they’ve also seen Donna access her sexual awakening by wearing Laura’s sunglasses. Mad Girl’s Love Song is the kind of book Donna would have written about Laura Palmer: endowing talismanic power to incidents and items in lieu of presenting the facts of her life and why she is worth discussion.

8. “Although I thought [Plath] might be awfully good, I was on the cusp a little on how she might fit in. Her behavior was almost a performance, which I found a bit of a problem. You might be there another day and find an entirely different personality.” – Gigi Marion, college department, Mademoiselle

9. Eddie Cohen chastised Plath for her complete inability to be spontaneous, and the roots, extremes, and repercussions of her constant performance are explored fully in Mad Girl’s Love Song. Mademoiselle‘s ambivalence about Plath provides a great launching pad for a vital paragraph on the magazine’s own artificiality. The way the magazine fully constructed the “New York” experience that the co-ed guest editors has for too long gotten off without comment, but it is so much a part of what powers the Bell Jar, to wit, the conclusion may justifiably be drawn, it made a serious impact on Plath. It’s one thing to put on a face and look the sweetest and the most congenial, it’s another to play along with the mass hallucination that high-rise parties with hired dates have any place in reality.

10. “It was a lunch designed for the girls to get to know one another a little better, and we were at that stage where we were watching one another very carefully, all of us groping to see what we should do, how we should behave. Very shortly after we were seated—at this nice table with a white table-cloth—a large bowl of caviar was served. The caviar was supposed to be for everyone on the table, but Sylvia reached out for it, pulled it in front of her, and began eating. She proceeded to eat the whole bowlful of caviar with a spoon. I remember thinking to myself ‘how rude’…” – Ann Burnside Love, guest merchandise coordinator READ MORE >

April 2nd, 2013 / 2:23 pm

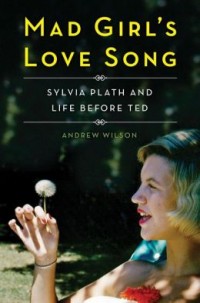

PR Today, 1928: Vice Magazine in The New Yorker

There is this all-consuming article in the New Yorker about the frequently confusing, possibly acceptable hipster-media-capitalism of Vice Magazine (the TV show), in the current cultural context. The talk of the town seems to be that Vice has sold out better than anyone else, that not selling out is failing, and that authenticity is for the poor or the soon-to-be-rich. Progressive political will, funded by corporations, and fueled by boring white-guy-Brooklyn hedonism, is the only mindgame in town.

Enter Edward Bernays: the man behind the men behind the reason you feel something when you buy something. The guy who sold soft Freud to hard markets.

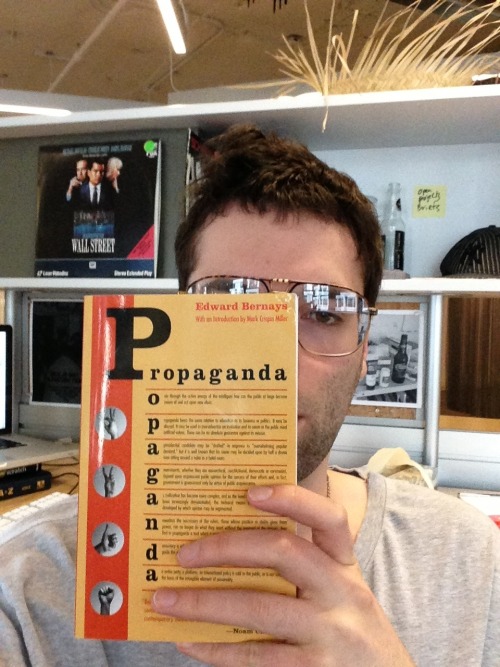

Crapalachia: A Biography of a Place by Scott McClanahan

Crapalachia: A Biography of a Place

Crapalachia: A Biography of a Place

by Scott McClanahan

Two Dollar Radio, March 2013

192 pages / $16 Buy from Amazon or Two Dollar Radio

To me Rainelle, West Virginia is synonymous with snow days. When I was growing up on Muddy Creek Mountain outside Alderson, listening to early morning school cancelations on 99.5 The Big Dawg In Country, it seemed like the kids in Rainelle always got the day off. Rainelle was in the same county as the town I went to school in but it lay just far north enough to ensure that it got an icing thick layer of snow on days when we got only dustings. As I walked to meet the school bus I thought about all those lucky-son-of-a-bitch kids in Rainelle at home in their pajamas watching T.V.

Rainelle is the hometown of Scott McClanahan and though I have never met him, part of the magic that McClanahan weaves into all of his writing is his ability to make you feel that you have known him all your life.

Rainelle is the setting for most of McClanahan’s stories, that and Danese, an even smaller community which serves as the main setting for his newest book Crapalachia: A Biography of a Place. Rainelle and Danese, the names, like those of two mythical twins, ring with memories and meanings just out of reach. Names are important to McClanahan, the names of his Grandma Ruby’s 13 children (each and every name ended in Y), the names of the 11 siblings of McClanahan’s grandfather (5 of whom killed themselves), the names of the faraway places the family moved off to, the names of the people etched onto McClanahan’s own heart.

It is McClanahan’s heart that speaks most loudly in Crapalachia. Though his prose often leans on the side of overly simple and abruptly declarative, the beauty in the writing comes from the fact that McClanahan seems to be dictating his very pulse. And in the midst of reading it you begin to realize that his pulse is matched by your own, that the room is filled with beating hearts, his, yours, and those of all of your mingled memories and “a million crazy babies.” Most importantly, McClanahan seems to be saying, he is alive and so are you and despite all odds so is this ageless place he calls Crapalachia. It is the defiance in the writing that is breathtaking, the very aliveness of this voice in the face of all those dead: the thousands and thousands of dead miners, the dead of the Hawk’s Nest Tunnel, the dead of the Sago Mine Disaster, the dead of the Buffalo Creek Flood, the dead of hunger, the dead of a death by their own hands.

April 1st, 2013 / 12:00 pm

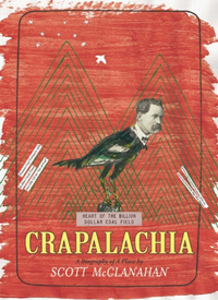

25 Points: 3 Novels by Barry N. Malzberg (Beyond Apollo, The Men Inside, & Galaxies)

Beyond Apollo | 1972, Random House | 156 pages

The Men Inside | 1973, Prestige Books | 175 pages

Galaxies | 1975, Pyramid Books | 128 pages

(Note: all three of these books are out of print, but cheap used copies can be found. In Chicago, I bought Beyond Apollo for $2.95 at Myopic Books (in Wicker Park) and The Men Inside for $3 at Bucket O’ Blood Books and Records (Logan Square). Galaxies I purchased used through Amazon for $1.25 + s/h.)

1. On 15 August 2011, my pal Jeremy M. Davies emailed me and said that I should look for a book called Galaxies by Barry N. Malzberg because it was “seriously beyond belief.”

I’m ashamed to say it took me until earlier this year to pick up a copy and read it. However, once I got started, I finished it under 24 hours.

2. Barry N. Malzberg was born in 1939. Since 1968, he’s written at least 66 books, if not more. (He’s worked under ten different names that I know of, which complicates compiling a full list.) Dozens of them are science-fiction novels—at least in theory. He’s also written story collections, essay collections, movie novelizations, crime novels, and pornography.

3. Galaxies (1975) at first glance tells the story of a young astronaut, Lena Thomas, the sole crew member of the spaceship Skipstone. Her cargo is an immense tank of goo filled with 515 human corpses. It’s the year 3902 and a person can pay to have his/her body ferried into space after death in the hopes that cosmic radiation will revive them.

Midway through the voyage, the Skipstone falls into a black hole, and the majority of the novel’s plot deals with Lena’s attempt to escape the ensuing hallucinatory free fall. During that timeless time she repeatedly dies and is reborn, recalls her lover John, consults with cyborg engineers, and communes with the dead, who have psychically reawakened.

But that’s not really what Galaxies is about.

4. Rather, Galaxies is a work of metafiction, concerned with its own creation, and presented as Malzberg’s notes on how he would write the novel Galaxies, if only he could. (He maintains that the novel is impossible to complete with present knowledge.) As such, most scenes are outlined rather than dramatically depicted. For instance, Chapter 29 begins:

And here could run yet another moody flashback concerning Lena’s relationship with John, dropped in to provide color and poignance, augmenting the mood of despair. Long sexual passages here could alternate with painful streams of consciousness in the present. Sex and space, orgasm and isolation could run counterpoint, and the author’s gifts for irony, which are not modest, would be exhibited to their fullest range. Also, in the traditions of modern science fiction, the sex scenes could be quite titillating, render the novel some extraliterary interest. A construct like this could use all the extraliterary interest it could get.

But even that’s not really what Galaxies is about.

6. Rather, Galaxies is about what science-fiction should look like in the year 1975. Malzberg is surveying contemporary literature and asking: How should science-fiction respond to the then-recent literary experiments of John Cheever, John Barth, Donald Barthelme, Joyce Carol Oates, Philip Roth, and others?

7. I’m not making this up. On page 48 Malzberg writes:

For instance, as the ship falls, there could be some elaboration on the suggestion that neutron stars might be pulsars which would be most intriguing, if the reader has not been intrigued sufficiently by the notion that all of “life” as we understand it when we glimpse the heavens may be merely an incidental by-product of the cycle of neutron stars.

So there, Cheever, Barth, Barthelme, Oates. What in the collected works would touch that for angst?

8. Malzberg calls those authors out again on page 85:

“Madness,” Lena says, shaking her head, “that’s utter madness,” but the author, busily pulling the handles of this little dumb show, sweating behind the canvas, casting a nearsighted, astigmatic eye every now and then through the cardboard of the set to see whether the audience is paying attention, how the audience is taking all of this, is thinking take that Barth, Barthelme, Roth, or Oates! Pace Bellow and Malamud, and may your Guggenheims multiply, but what have any of you or those unnamed created to compare with this?

9. If I haven’t convinced you yet to spend $2–3 on a used copy of Galaxies, you might as well quit reading now.

April 1st, 2013 / 8:01 am