Let’s Plunder Baudelaire

My French hasn’t happened, barely has my English. What might allow me to translate Baudelaire any better? Have you seen the poorly Christian way being had with some of his lines?

Ses cris me déchiraient la fibre

is

Her screaming would drive me crazy

Her crying knifed the heart in me

Her screechings drilled me like a tooth

Her crying upset me horribly

Her crying tears me apart

Her nagging tore at every part of me

Save for contour, pasteurization, cluck by region, I know my reek, but this line from Le Vin de l’assassin or The Murder’s Wine or The Assassin’s Wine or The Wine of the Assassin or Sippy Vindicator is rarely caught right. Why should it be? Can we span our whip from known to felt? I’m saying it doesn’t wow to take a nineteenth century dandy with a peanut head, and of such a floral, copulating rigor, and pinch him to “drive me crazy.” He’s not young Britney batting curls. Baudelaire consistently scarfed his wig. What is the direct UN transcript of this lovely purple? The hissy fit runs deeper into Satan. He’s not workshopping; he’s pissing blood. I don’t care, because I’m translating the poem right now, out of French and without rhyme. I’m going to say Michael Robbins and few others on his level have by their genius made rhyming their property. I keep very afraid of my betters. Especially Robbins. I chose my last twenty dollars for his book when I was starving in Austin. It gave me a lot of meals to look up to, so if I rhyme it’s just a glitch in the word salad, sir. Please. I berate my own underneaths. I live in fear. Ariana Reines having brilliantly done legitimate work translating Baudelaire – let me distinguish, too: This is simply an act of poetic necrophilia, mid-lobotomy.

Brief Notes on Johannes Göransson’s Poetry Foundation Posts

Rauan Klassnik already wrote a little bit responding to the first of Johannes Göransson’s recent ‘Corean Music’: Art and Violence posts at the Poetry Foundation blog. Part 3: “The Autobiographical Account of The Diabolical Music of Translation and Kitsch,” starts with the lines:

Every immigrant knows that it’s impossible to translate.

Every immigrant knows that it’s impossible not to.

As the post introduces some of JG’s own autobiographical context into the discussion, these opening lines push me to immediately delve into my own autobiography and the troubles of translation, translating between languages, yes, but also between cultures, histories, philosophies, beings. (Also I’m taken back to Bhanu Kapil’s Incubation: A Space for Monsters…)

He also quotes Kim Hyesoon from an interview:

Yes, poems are ways of saying you clearly remember the day of your death and your tomb. When I am writing poetry, I relive my days when a woman inside me dies many times. My body is full of graves. A sepulcher is dug up, and a young girl comes out of it with her dusty hands in tears. A lady who is a young girl and an old girl at the same time feels the presence of the young girl. I feel that the 15-year-old me and the 50-year-old me come out of the sepulcher through an illegal excavation. Time is not a straight line, but just a flat hell, like a desert. I am a tomb robber who is robbing my own tomb. Things from my tomb are exhibited under the radiant sun. Every time it happens I feel crude.

This feels really apt to me. The sort of violence of extracting different versions of a self, extracting memories and translating those memories, a thousand lives and deaths trapped in the strange balance of a body, like a fucked up game of Operation.

Recently I found some of my mother’s old photo albums, an old yearbook, photos of her as far back as junior high, some from before she met my dad. I had never seen most of these photos before. I looked through each album with my dad, recording his thoughts, recollections, questions as we picked her out in group and class photos, speculated on her age and context. My dad had also not seen many of these photos before. It was a strange piecing together of an identity, an identity that is altogether very clear in our minds. She was his wife. She was my mother. And an identity, that instead of becoming magnified, clarified, starts to become shattered and fragmented. It is a violent and uncomfortable process. Who is this woman at the beach in the photos? What version of my mother is this? How do I extract her ghost, my ghost, from these old images?

It is strange to think about the violence of translation. JG writes:

It was an abusive translation project.

It was catastrophic translation.

I haven’t recovered yet.

I haven’t recovered from the violence and I haven’t recovered from the beauty of being drowned in a foreign language, a language full of strange and alluring words like “faggot” and “weirdo.”

I’m not doing a full response of JG’s posts, and regardless, you should head over to the Poetry Foundation and read them yourself, but mostly I’m currently too self-absorbed to make any connections that aren’t related to my own peculiar and particular situation. JG’s posts are full of interesting questions, including circling around an ancient one about the potential of art. I’ll stop here for now, but curious to hear from others who might be engaging with these ideas in different ways…

The Natural Dissolution of Fleeting-Improvised Men by Gabriel Blackwell

The Natural Dissolution of Fleeting-Improvised Men

The Natural Dissolution of Fleeting-Improvised Men

by Gabriel Blackwell

Civil Coping Mechanisms, Available October 2013

Gabriel Blackwell channels H.P. Lovecraft in The Natural Dissolution of Fleeting-Improvised Men, an epistolary metafiction that serves as part of a trilogy of works connected by his earlier Shadow Man and Critique of Pure Reason. In the introduction, Blackwell reveals that he has set out to Providence, Rhode Island, to find his girlfriend, Jessica, who disappeared while he was finishing the writing of Shadow Man. During that trek to Providence, he discovers the final letter of H.P. Lovecraft and that last message comprises most of the book in a footnoted poioumena intertwining his own desperate search with Lovecraft’s pestilential descent into madness. This isn’t just a pastiche of Lovecraft though, who died of intestinal cancer and whose last years were the most painfully productive. The mystery takes on a bizarre twist when he discovers the letter is addressed to another Gabriel Blackwell. Horror gets deconstructed and Lovecraft is retrofitted in a work that is less concerned with categorization than the ‘dissolution’ of existence. Experience itself becomes suspect as does the scholarship of pain. Blackwell, the meta character in the book versus the actual author, is typing out Lovecraft’s final letter. But as he does so, he is faced with a troubling revelation:

“That is, coming to the end of the particular sentence I was typing, I would look back over its analogue in the letter and would be unable to find even a third of what I had typed… This was undoubtedly made worse by the thicket of Lovecraft’s characters, by their lack of line breaks and paragraph breaks and even space between words, but it was also a quality of the prose. The events I was transcribing had not only not happened in life but not happened in the letter, either.”

It’s a setup for a mystery, a noir doused in elements of phantasmagoria with a magical lantern projecting Blackwell’s prose. The events described within are as gruesome and macabre as a Lovecraft story and in fact could be mistaken for one of his short stories. Horrible things are happening to the people in Lovecraft’s vicinity as in “this disgusting pile” that “was the remains of a man after he had been devoured and regurgitated by some horrid fungus or slime mold!” The grippe in his belly is devouring him from within and his mental state is corrupted into a decay and darkness that overwhelms his vision as much as his being:

“This thing in the basement was some sort of central node, a convergence of nerves. It was dowered with dark properties and obedient to dark laws; darkness was its element as air is the cloud’s, as water is the sea’s- the clashing, gnashing plates of its existence, in all of their horrifying splendor, were not so much dark as in aspect as of the dark…”

What adds a twist and requires a philological scalpel are the footnotes Blackwell uses to annotate his transcription of the letter. Much of the notes involves further elaboration of the plot details he outlines in his introduction. But there are disturbing intimations that require deciphering, a linguistic sonar to extrapolate from the echoes of meta-Blackwell’s journey. As his pursuit of Jessica becomes more desperate, his physical plight degenerates in a downward progression similar to Lovecraft’s. He is starving, cold, and suffering anemia. His body gets soaked with ink to the point where he does not recognize himself. With his impoverishment, things only get worse:

“I had a chronic inflammation around my anus- it itched all of the time and stung like a cut doused with hydrogen peroxide when wetted. I worried that I had soiled myself because of the wetness there, but always it was only blood.”

August 12th, 2013 / 11:00 am

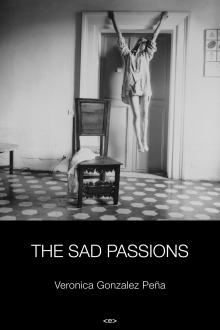

The Sad Passions

The Sad Passions

The Sad Passions

by Veronica Gonzalez Peña

Semiotext(e) / Native Agents, May 2013

344 pages / $17.95 Buy from Amazon or MIT Press

The cover of Veronica Gonzalez Peña’s novel, The Sad Passions keeps changing on me. It’s a Francesca Woodman photo—a woman or an apparition. She is suspended in air or hanging on for dear life. She is a martyr or a demon. She is in pain or in the realm of the sublime. She is being crucified or being exorcised or being made a martyr. I keep approaching the possibilities of this puzzling image and watch the figure grow porous the longer I look. She is an unstable subject and as I make my way through the novel, it’s the chair that grows more present, more formed than the person. Something in it’s gaping emptiness, the carelessly draped cloth suggesting a body, now gone. I like the way the image moves with this novel, the way the absence becomes the presence. Veronica Gonzalez Peña does not write absence as a form of lack, her absence froths and grows agitated, it fills up the page with pulsing need.

The Sad Passions follows four sisters, their lives punctuated by their mother’s mental illness, by an inheritance of cumulative ancestral pain. The sisters, while distinctly different from one another, all grapple with the fear that their mother’s madness might become their own, that their identities might slip quietly, at any trigger. One gets a sense that at the turning of the page one sister might become the other or that they might all become their mother or they might all melt into a composite figure.

It’s precisely this plurality, this repetition/duplication of identity that is at the center. In a chapter told from the perspective of the 2nd eldest sister Julia, Gonzalez Peña writes,

Each chapter is told from the perspective of a different character, often retelling the same traumatic events but with startling different sentiment. There is something in the retelling process, the approaching of truth by making different angled entries but never quite locating truth, dancing towards it—if only to say that understanding trauma, by nature is a process of de-centering, that understanding must be choral.

August 12th, 2013 / 11:00 am

The Girlfriend Game

The Girlfriend Game

The Girlfriend Game

by Nick Antosca

Word Riot Press, June 2013

174 pages / $15.95 Buy from Word Riot or Amazon

“Every time we play the game, it brings us a little closer together.” So declares the title story of Nick Antosca’s poignant and feral new collection.

It’s not incidental that the book takes its title from this story. Grittier and less gothically stylized than Midnight Picnic (though quasi-supernatural dogs are no less present), the twelve stories collected here are about human closeness – the lack of it, the search for it, and the fear of it when it comes. They open with the premise of men and women drawing one another in, and play out the game that follows until some grim resolution brings that round to an end, sometimes sparing the players and sometimes not.

There are ample rat beasts, humanoid amphibians, alien landings, and panic-inducing weather patterns crowding the sky, but what’s scariest here are the ways in which, as a professor forlornly sleeping with her student puts it, “there was no escaping it, the violent strangeness of people.” Unlike in more common horror writing, where the monstrous crawls in unbidden from the basement or from another dimension, the people in Antosca’s stories call it up in one another, and access it via others in themselves.

In many of these stories, which tend to center on depressive twentysomethings in nondescript Brooklyn-based situations, people pursue one other across spiritual and geographical distances, often out of the city and into the woods. The woods, as in Midnight Picnic, are at once a sanctum of simplicity and innocence, and an arena for unleashing extreme and unpunished violence. Their sparseness of population seems to offer relief from the city’s human weight, but, as a setting for a certain kind of showdown, they serve an opposite purpose: they draw the pursuer and the pursued closer together by purging all witnesses and middlemen.

Weirdly, the violence this enables becomes a form of innocence. Beneath all the Facebook and iPhone surface noise, The Girlfriend Game fleshes out a primitive vision of society where dismemberment with knives and meathooks is a valid and even productive mode of interaction. It’s maybe the only way to play the game without tricking the other person. As one woods-bound narrator puts it, “I began to understand that only one thing might bring me peace – not fantasies of murder, but murder. I started planning.”

There are no misfires, but my four favorite stories are “Mammals,” the most purely horrific, “Winter Was Hard,” the baddest-ass, “Migrations,” the saddest and most enigmatic, and “Carnal Quartet,” which nails the vibe of darkening post-coital rooms where a hint of dread – maybe just passing time, maybe something demonic and amiss – creeps in to divide the dozing lovers, while at the same time enveloping them both.

August 9th, 2013 / 11:00 am

Joseph Lease’s Testify

Testify

Testify

by Joseph Lease

Coffee House Press, 2011

63 pages / $16 Buy from Amazon or Coffee House Press

In his latest collection, Testify, Joseph Lease pulls words from a wide stream of diction, using vastly different textures to make the fullest contact with his readers. Re-casting lines from multiple news sources, Lease sets up the problematic linguistic backdrop of the current media and the gaping lack of a faithful source of social, economic, or political truth. The action of writing, even the intention to “turn off the shooting try our new / daydream and / try our // new rights,” offers an intervention, an alternative to the automatic moving walkway that propels us always in the direction of consumerist distraction, militarized deception and political numbness.

This mixing of language sources runs horizontally and vertically throughout the poems, always accompanied by what seems like the intention to write into language a new kind of critical and essential love. With lines like “We’re going back home to / night pushes through money” and “write to your congressional representative, / write to, keep imagining—,” these poems literally invite readers to return to a more compassionate model of democracy, in which there is a “home” to return to, perhaps the home of collective action around the demand for true social investment outside of capital or military “growth.”

Made of four discrete sections, “America,” Torn and Frayed,” “Send My Roots Rain,” and “Magic,” Testify sings from a lyric “I” that is at once outraged, grieving, tender and hopeful. Lease retraces phrases and rhythms to build tremendous richness and depth over the seventy-five-page work. Bleeding through the borders of its separate movements, the book circles back, widening and deepening the connection between speaker, listener and poem. Some of Testify’s parallel undertones are subsurface as a pulse—and I can’t be sure if it’s my heart that’s making them or Lease’s. To me, this is the central force of Lease’s work; this beautiful tangle of breathing and moving makes direct contact, which Lease has forged through a kind of shared organ. Take, for example, the opening lines to “America,” the poem that comprises Testify’s first section: “America // Try saying wren. // It’s midnight // in my body, 4 a.m. in my body, breading and olives and / cherries. Wait, it’s all rotten. How am I ever. Oh notebook.”

From this first line Lease roots down immediately in both body and voice. His focus on effort and embodiment in the face of disorientation, dismay and deception, creates a space for shared experience and hope.

Moving quickly into war on the next line, Lease connects a national identity crisis, “A clown explains the war….Oh CNN,” to a personal one, “I have to run, eat less junk.” The effect is to model a consciousness of citizenship that never seeks to isolate the self from the collective: “say democracy: say free and responsible government, say / popular consent.”

August 9th, 2013 / 11:00 am

The Novelist?

Fun new game where you get to control, via a ghost, a depressed novelist trying not to destroy his family. Read the full article (I recommend the video) over at Kotaku.

“I started a micropress, published my own chapbook, and got in a car to drive around the country promoting it at any place that will return my e-mails and phone calls not because I think the system is broken. I just think the system is bigger than it appears to be.” — from a really entertaining and no-lavender-aerosol take on DIY micropublishing and touring by Ryan Werner at Passages North

Thank You For Your Sperm

Thank You For Your Sperm

Thank You For Your Sperm

by Marcus Speh

MadHat Press, 2013

188 pages / $15.00 buy from MadHat Press or Amazon

Rating: 8.9

Marcus Speh explores the tender side of absurdity with Thank You for Your Sperm. Though this is flash fiction it lingers in the mind for much longer. Entire histories are suggested in these small pieces. Not a word is wasted either. From the title to the last line Marcus Speh uses language economically. Words playfully jump across the page opening entirely new histories within histories. Geography is a key part of these stories as geography too can suggest a mood with a simple word or two. Berlin specifically gets rather affectionate treatment. How all of this comes together is quite impressive. READ MORE >

August 8th, 2013 / 12:10 pm