The Talented Mr. Ripley

Dear Marge,

Sorry for not writing earlier, but I’ve joined Mors Tua Vita Mea, a writer’s colony outside of Rome. It’s run by Giancarlo Ditrapano, the editor of Tyrant Books, and Chelsea Hodson, a literary darling. Everyone is very grateful to be here, the way Americans are when they are not in the United States. They all look like they are in Joy Division or Counting Crows.

Workshops meet every morning for two hours. At first, Giancarlo used a small chalkboard panel to communicate, but often misplaced the eraser; by the end of the workshops, it looked like he was holding a Cy Twombly masterpiece. After some encouragement to jump forward a century, he bought a white board which, when we considered the subject matter of everyone’s manuscript, became known as the “white bored.” The only person of color there was Giancarlo’s personified member, whom he invoked incessantly. And the color is purple.

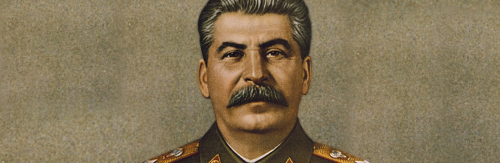

READ MORE >Some Good Books About A Bad Man

Stalin

Edvard Radzinsky, H.T. Willets (Translator)

Once, while partying with his comrades, Stalin wondered aloud whether a star in the night sky was Cassiopeia or Orion. Comrade Molotov and Comrade Kaganovich couldn’t agree on the answer, so they decided to call the planetarium. The man who answered the phone was a security officer, so he didn’t know. He promised to call them back. He then sent two other security officers in a black limousine to fetch the most well-known astronomer in Moscow. This was during the Great Terror, when Stalin had prominent scientists, writers, doctors, etc, randomly arrested in the middle of the night, then tortured, shot, or sent to the gulag. When the black limo pulled up at the first house, the astronomer, whose friend Numerov was arrested just the previous week, had a heart attack before he could answer the door. They decided to visit a second astronomer. When the second astronomer saw the black limo pull up, rather than risk torture and imprisonment, he threw himself out of the window. The third astronomer shot himself. The fourth astronomer answered “Cassiopeia” then urinated himself. By the time word got back to the party, everyone had gone to bed.

Stalin: Volume I: Paradoxes of Power, 1878-1928

Stephen Kotkin

When Lenin and the Bolsheviks took power, they no idea how to run a country. They made stuff up as they went along. They commandeered a girls finishing school in Smolny, the headmistress of which kept her office next to Lenin. Stalin was randomly appointed head of the People’s Commissariat of Nationalities, his first real job in years. He sat in his office with his deputy Pestkowski and waited for phonecalls. Trotsky tried to take over the tsar’s Ministry of Foreign Affairs building, but the employees just laughed him out the door. When Trotsky came back with a small group of armed men, the employees fled. Trotsky stole what money they left behind. When Pestkowski succeeded in stealing a portion of the cash from Trotsky, he was named head of the State Bank.

Young Stalin

Simon Sebag Montefiore

Young Stalin’s unofficial role in the early days of the party was to rob, hold people for ransom, and extort funds for the revolution. He spent many years “expropriating funds” in oil rich Baku, a city in Azerbaijan with flame-spewing refineries and elaborate palaces built by its many oil barons. One oil baron named Musa was kidnapped by the Bolsheviks, but refused to give them money. “Of course, you can slice me up,” he said, “but then you’ll get nothing.” Stalin, who normally preferred to work in the shadows, decided to meet in private with Musa. After a 10 minute conversation, the oil baron decided to pay up. Later the same year, Musa was kidnapped by the Bolsheviks a second time. This time, he paid up immediately. Musa, like most wealthy peasants after 1917, was stripped of his fortune, but not before he received a note from Comrade Stalin that read, “Thank you for your generous contributions to the revolution.”

Maison Book Girl / karma -Mii remix-

I think I’m drawn to bands with “book” in their name.

YOU FEEL ME

I HALF THOUGHT I WAS GOING TO KILL MYSELF IN 2018, a few months before the launch of my debut novel. All I ever wanted was to be loved, to feel loved, and to write books. I woke up nearly every day reading and writing for the past ten years and suddenly, in October 2018, I didn’t want that shit anymore, my body could not write, my body was not hungry, I wanted to die and disappear instead. King of Joy was to be published in March 2019 and I wondered if I would be alive in March 2019.

Clouds move at my favorite speeds. Walking up hills makes me dream and want to live again. I burn my knees walking everywhere. No matter how I feel about nature, no matter how much in love I am, my face stays the same, my swagger endless monotone. There is a part of me that will always want to call you, Baby. I turn everything that has nearly killed me into entertainment. I put all my eggs in one basket and I smash the basket.

I am walking down some street in Los Angeles and I can see the Hollywood sign. I am here for Brad Listi and his podcast. Aloe Vera plants, palm trees, cracked sidewalks: all of this, I remember, is my shit. I hate it so much here. It is Friday, March 15th, and I am blitzed out of my skull. I smoke fatty, I smoke fatty, I smoke fatty. I can see Brad and Twiggy on the front steps of his house and I have an out-of-body experience; it’s as though the sky around my face clouds and watches me like a camera. I have barely slept, I miss New York, I miss Seattle, and my body moves like a ghost from room to room, following Brad Listi into his incandescent pool house.

In the interview, I feel enlightened as hell. I say something like, “If I had a choice of writing ten books and killing myself versus writing four books and living a happy life, I would hope to choose the latter.”

You have to know that rest is writing, too. Finding love is writing, too. Doing fucking nothing is writing, too.

Brad has a handsome face. I can feel his whole life from the careful way he walks through his house, and I can tell he is a kind man. Cars nearly run me over. The sun is gorgeous. I leave Los Angeles the fuck behind.

There is a calm to the world, a drop in the ocean. I have to pull it out of me like a sword in a stone, like a knife in the abdomen, like a very good reminder. I attempt my life. My friends love me. I came here, like a reckoner, to belong in your room. I have so much more to say.

Ily

At some point, I started to notice I wanted to modify adverbs with a word before the adverb. Instead of writing, “He quickly ate the mango in a distracted manner,” I wanted to write, “He distractedily quickly ate the mango,” because, among other reasons, I wanted to be more concise.

I talked to some people about this a little. In 2018, for example, I tweeted this. Later, I named the new-seeming type of word “ily” because to use it you just add “ily” to the word you want to become an “ily.”

An “ily” is a word that qualifies—or adverbs—an adverb. I was going to put ilies in my next novel, and had some in it for a while (“acceleratingily increasing complexication,” “unconsciousily habitually dissimulating”), but then took them out.

More examples:

She put the large door—that we’d found and carried around—endearingily awkwardly in front of the home area.

A longily concisely written account of skydiving.

Werewolves and White Men: A Conversation with Filmmaker Nick Verdi

Nick Verdi’s films are ragged. Staggeringly no budget but brimming with hideous feeling, each feels like a dry infection. As informed by the work of Jem Cohen and Kelly Reichardt as they are straight-to-video schlock, Verdi’s films function as direct lines into his fascinations: the ease with which communication breaks down; the violence inflicted by (and upon) the young; a creeping sense of apocalypse that no one else seems to notice.

Last year Nick asked me to perform in his latest short film, Angel of the Night, centering around a 35-year-old university employee whose only sincere interactions are when he’s harassing the student body. During a pre-production workshop, Verdi showed me videos of Sam Hyde, John Maus and werewolves for reference. “We’re such strange creatures, aren’t we?” he said. “White men, I mean.”

Nick Verdi: There’s this one movie Moon of the Wolf. It’s such a middle of the road, ABC movie-of-the-week from 1972. It’s a murder mystery set in Louisiana swamp land, and there’s this rich family that owns the town who lives on this giant plantation. And of course, the head of the family—this guy Andrew Rodanthe—ends up being a werewolf. He’s killing people. He kills this girl Ellie—this poor girl. “Why would this poor girl know Andrew Rodanthe—this rich white guy who owns the town?” And it’s because they were lovers and all this shit, you know. But Andrew Rodanthe is like the perfect “unreflective, refusing to reflect, emotionally detached white guy” that has spent all day completely pent up and in hell, and at night it all comes out and he does awful things, the worst fucking things because the more he doesn’t look at himself the worse it is.

And it’d always been, the explanation for the werewolfism in the movie is the sister character— who’s Barbara Rush—talking about Granddaddy. “Granddaddy always had these spells upstairs.” Then years later she realizes it was because he was drinking. And then Andrew is having these same spells. And it’s like, that’s the thing right there. The drinking is the werewolfism. You think about having some blocked memory of seeing your drunk father. The transformation. You know what I mean? It’s the eeriness, the uncanniness of the home being the safe place, but also where the most fucked up things happen. And this sense of: it’s the man with the button down shirt that is the worst thing you know. It’s all these strange, strange things I feel. It’s the main thing I always think about, you know what I mean?

B.R. Yeager: You’ve said that’s one of the things that draws you to John Maus—the way he looks like he’s about to burst out of a tight button down shirt.

NV: Exactly. It’s like I want to see the truth come out in the most violent eruption at whatever expense. The limit of this—this physical body, this form. You come against the limit of your body, and you realize you are not your body. What are you? You know, all this stuff. It’s a tornado inside this person, like what the fuck is going on inside this person, you know?

BRY: You’re talking about wanting the truth to come out, even when (or especially when) the truth is monstrous. Like letting the monstrosity out to be acknowledged. Even though that might be objectively better than holding it in, it’s still terrifying, and maybe confirming things you wish weren’t true.

NV: No, totally—like, the core is a refusal to accept truth. The more you refuse it, the worse it comes back.

BRY: Right.

NV: So it’s always like the refusal to actually self-reflect on whatever—on what you are, on who you are and those things. On things you feel and things you think, you know? Where it’s like you simply have an inability or refusal to self-reflect, or deal for whatever reason.

This topic [werewolves]—this sounds like we’re talking about white men. You know what I mean? This sounds very much like we’re talking about white men right now—the refusal to accept truth, the refusal to accept the truth in yourself. The refusal to accept.

BRY: Which only makes you more monstrous. By hiding it. Because you think that hiding your monstrous aspects will keep you from being a monster. When it’s the opposite. If you don’t figure out how to self-reflect and acknowledge the shitty parts inside you, like address that stuff, the monstrous stuff just bursts out.

NV: Right. Right. Yeah. The other attributes between werewolves and white men is this sense of … you know the Universal The Wolf Man, the Lawrence Talbot character? It’s this shameful, tortured existence. You know what I mean? Like hiding his crying all the time. And that kind of weird sense of faking it through the day but you’re nothing inside. You know? You’re absolutely nothing. And then at night that nothing completely overcomes you. In a simple sense it’s like when someone goes home and gets hammered, and the only way they get any sense of release is through getting hammered and being the worst, as opposed to having some sort of cathartic love of yourself, like selflove being the impossible thing for guys to do. It’s like you’re pretending forever that you’re still doing the 14-year-old dude thing where it’s like “whatever,” when you really have to let that go.

So really I think that tension comes from the refusal of reality, and reality continuously hitting you in the face. And with the werewolf, the tension gets to the point that the fight back is just an absolute nightmare and you succumb to it.

Watch Nick Verdi’s films on Vimeo

Angel of the Night will be released in late September on nobudge.com

August 26th, 2020 / 12:53 pm

Writing Against the Censor

Before Covid arrived and ruined everything, I was emailing with a writer I look up to, asking him about—I guess you would call it—procrastination. This was maybe January. I’d developed a bad habit of spending my Sundays chained to the computer, worrying over writing, sometimes trying to get blood from a stone, feeling like I wasn’t productive if I ripped myself away and did things. It was a bad state of mind and a worse state of creation—even worse when you think about what was coming. The writer I was talking to said:

I’d say–when you’re ready, write with fury and keep going–when you get tired, go out, take a walk, don’t think about the story; then when you’re ready, go back in and keep going. The writing mode is the opposite of the writing mode; the writing mode is a dream mode, similar to a daydream mode, or even more, a reading mode.

I’ve let that guide me these last sixish months of trying to write—despite knowing that the world as it was before March might never return—writing which sometimes resembles simply freaking out at the difficulty of writing, let alone finishing anything, and which at such times results in my simply migrating to social media and engaging in the supreme ease of participating in the cycle of rage and anxious irony that defines it, in particular making mountaintop-sounding proclamations about politics in long, bitter posts on Facebook (a favorite hobby of mine). In those moments writing fiction feels singularly useless. There is a world of active, fast conflict happening online. But the page is slow and no one likes it until it’s done, and probably not even then.

I think that hesitation before the page comes, like most mental paralysis, from fear. Will I be able to do it today? Am I a fake? Am I writing the wrong thing? In therapy sessions, I call it a “censor.” I might write a sentence, or a paragraph, and it’ll turn out less than good. So better to write nothing at all. Nothing lost, nothing attempted—but everything lost, because that fear you (I) felt at the computer screen echoes through the day and into the night and invades my dreams—the dream mode is no more a dream mode. Once it takes hold, I find, the censor censors everything.

But then there are mornings when the censor shuts off, or it’s like it wasn’t ever there, or maybe like it’s revealed to have been something that was somehow only ever the product of my own will, my own decision making. There’s no incessant “no”—no groans of, “You can’t do that because you might fail”—only daydreaming at the keyboard, playing a bit, kicking around images and sounds and half-remembered imprints of, for instance, a gas station in Tampa from twelve years ago. Then everything opens up and ambition and ego go mostly quiet—you can still hear them but they’re whimpering somewhere in the background, and it’s all about the expansion and contraction of an invented voice through the always-weird medium of words. Writing, in other words. The other mode—the censored mode, driven by fear—I don’t think I’d call that writing. It’s typing. It also might be a necessary part of the process, those many nothing attempts.

Anyway, welcome back, HTMLGiant.

Toys

by sung

Ed: There is depiction and/or mention of suicide and child sexual abuse in this, jsyk. Take care of yrself.

If you hold your breath, doesn’t time stop.

In her world there’s no wondering what to wear and everything fits. She can stand for hours without getting tired and she always feels at home. Her name is molded a thousand times in glossy plastic so she never has to wonder who she is.

I want her pore-less skin. I want her fixed smile. I want to be her. You have no idea how bad it gets.

The thing about a Polly Pocket is that there’s not much you can actually do with one.

They come in plastic cases that open like clamshells to reveal tiny dollhouses inside, decorated according to common girlish themes such as tea parties, mermaids, and beauty salons. The classic Polly Pocket doll is less than an inch tall with stiff, joint-less arms. Her feet are fused together forming a circular base that snaps into pre-determined slots in a few locations such as in the kitchen or at the bathroom vanity. The house is in large part purely decorative.

It’s the kind of toy you stare at more than play with. It’s the kind of toy I stare at and cherish too much to touch.

I’m sitting on the balcony with a pink umbrella when it’s dry out. It’s summer. I’m five years old.

I’m sitting under the umbrella and daydreaming. I pretend the umbrella is my own little house. Some day someone will tell me this is a very autistic thing to do but the fact is not everything can be afforded the luxury of a name. My mother doesn’t remember this game but I sit here staring into space often. Everyone thinks there’s something wrong with me because this is how I wile away so many hours. I sit and stare a space into being.

Someone in a movie says things seem so big when you’re a kid.

I remember being a tall, ungainly thing. I remember being in the way.

There was this commercial in the early 90s where a little girl opens a bright pink box and out pops a doll. As the doll is engulfed in CGI sparkles, the narrator’s honeyed voice tells me to imagine a doll that grows up with me. She’s called My Little Friend. The doll emerges from the glittering fog transformed into a life-size version of herself, rosy face pressed against the little girl’s as they embrace.

I imagine she’s warm.

I imagine the future.

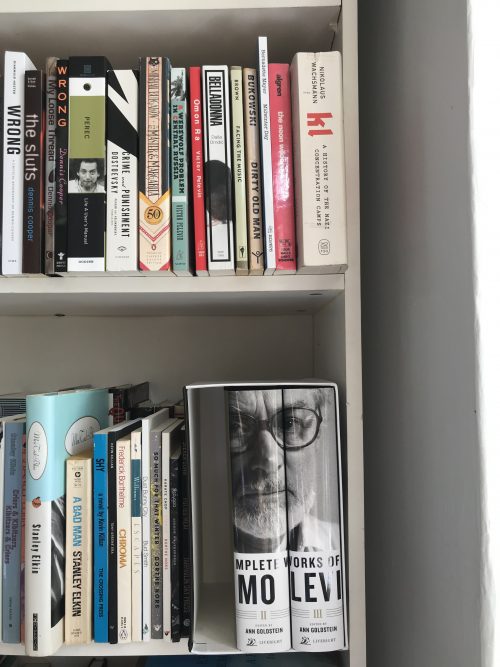

READ MORE >Places Where I Read Primo Levi’s If This is a Man

I bought The Complete Works of Primo Levi with unemployment money. It comes in a box and when the spines of the three volumes are put together they form the face of Primo Levi. When I am in my living room I can see Primo Levi and he watches me. We make eye contact. But I took the first volume out of the box and now he is missing a quarter of his face.

* * *

I am reading Levi’s first book, If This Is a Man, a memoir of his experience as an Italian Jew in Auschwitz. When the book was published in America it was given the title Survival in Auschwitz, a title almost as bad as Auschwitz for Dummies.

Put Auschwitz in the title or they won’t know it’s about Auschwitz, an editor must have said.

* * *

My great-bubby, Ethel Belgratsky, fled pogroms in what is now Ukraine long before the Holocaust and she lived in Montreal during the Second World War. But I don’t know what happened to the cousins and other relatives who never left. My Uncle’s wife’s mother survived the camps and fell in love with a Russian soldier. My grandfather—I call him Papa Howard—doesn’t know where our Novaks originate but the legend is that we are Lithuanian Jews. Litvaks. None of this is concrete to me. All of these people I never met swirl around in my head.

* * *

I like this book a lot. It is not a long book. I am reading it slowly because the sentences are rich and unique, simultaneously simple and complex, and the subject matter isn’t something I find myself able to breeze through. Every chapter is about life and death and pain and humiliation and hunger and thirst and hope and hopelessness and language and fear and the random stupidity of evil and innocence and cunning and chance and disease and excrement and chemistry and clothing and bowls and spoons and soup and bread and humor and fatigue and judgement and memory and war and almost no peace.

* * *

I read some of If This Is a Man on the blue couch in the living room in the morning. My back hurts. I don’t like our bed. Sometimes I sleep on this couch when I am sick of the way our bed is treating my back. It is winter and Primo Levi is in a crammed boxcar headed to Auschwitz. The men, women, children, and infants suffer “from thirst and cold.” Finally, after a long journey from Italy to Poland, the train stops. Primo and the woman who has been pressed against him for the entire journey, an acquaintance of his, say to each other “things that are not said among the living.” They say “farewell and it [i]s short; everybody s[ays] farewell to life through his neighbor.” Then the train car doors open and the men and women and children are separated by SS guards. The able-bodied men go one way and as for the women and children and old people, “the night swallow[s] them up, purely and simply.” The book is heavy in my hands. Each volume is a hardcover and Volume I is 747 pages long. IfThis Is a Man is the first book in Volume I and it ends on page 165. I am on page 16 and my eyes are wet after reading about a three-year-old named Emilia who had to be killed because she was a Jewish three-year-old. My hands and arms have to work to keep the book from falling onto my face.

READ MORE >What A Book Means

I’ve spent nearly all the hours since March in my apartment. So my attention in these last months has focused on, flitted by, or ignored my books—shelves and shelves of books—more often than in any other period of my life. Yet I’ve read little. I can blame distraction, fatigue, despondency—and I do. But the presence of my books, of so much paper and ink, is also for me a series of unanswered questions: What am I? What part of you do I serve? Do I serve anything at all?

Here is for me what a book has meant.

I’m five. The book is a cradle, but one held right in front of me. I can somehow be in it and outside of it. It’s a gift, a book—but a gift that doesn’t go away. A book is a place I can go anytime from anywhere. I’m not yet able to go there myself, or go alone, but I sense the possibility of this privacy. This possibility is scary, like a shadow of a bigger, stranger possibility that seems like the lives my parents live. An inexplicable life. A book is a path towards that life, but it’s also an escape from it because each book’s colors are so clearly more vivid, more real, than the life outside a book. I’m amazed that my parents don’t talk about this, this secret they open for me whenever we sit down to read.

I’m ten. I seek the secrets of books whenever I can. I’m convinced the worlds they contain are more real than the life of my bedroom, than the life of school. I suspect the books I run away into and the land of my back yard I run across are related in some deep way: that there is a shared wilderness in them, a wilderness which quietly and patiently rejects the status of the fence. I want desperately to make more of this wilderness. So I write. I write because writing and reading are both the act of bearing in my mind what must in all circumstances live. I know that the imagination is a realm which must be protected from the grays and metals and routines of the clothing racks, the grocery store, and homework. I know that what must live is being attacked by regular life, or what everyone else but regular readers call regular life. I hoard books, because of the perspicuity of my situation. And I hoard them because I love their shape, the grain of their pages, the smells they hide, the glint of their spines in every kind of light. I am a fugitive in the world because of the truth of books.

I’m fifteen. There are books, just a few, that scream the unsayable. This scream and its agony are a shelter. These books hide me. These books also make plain the fact that other people have worked so hard to reveal what’s hidden. That this is the role of a book: to reveal, to unearth, to dig up and tear open and point and stare. Reading and writing books is a way—the way, the only way—of being honest. I realize that not only must I continue to structure my life around books, but that books are escape tunnels leading away from the ordinary lies of living. I realize more vertiginously that I am responsible for building these tunnels. And that these tunnels must be beautiful—that books must be beautiful, as objects—because they must be habitable in case someone like me gets caught in them. Because, I suspect, we only ever get caught in them.

I’m twenty-one. The book is an event meant for other people. In making them, in editing and designing and soliciting them, I realize that books are events by which likeminded people are brought together. I view each book as an announcement, too: I have something important to say and I did my best to say it. Books can thus be judged by the social and financial context in which they were produced. Is this book’s announcement simply a commercial for its publisher, a little boon to the capital of that publishing company’s owners? If so, it can be scorned. Mocked. Or, ideally: ignored. The real shit, the real books announcing plain truths newly articulated, live among what our culture’s nervous gardeners call the weeds. The small press, the indie press: watchwords of those with good taste. Books are for and against: for the truth, for improvisation and innovation; against the dumb and redundant lies of the marketplace, against the formulaic and respectable. A book is an event for those rare good people to find and hold onto each other.

I’m twenty-six. A book is a piece of an infinite conversation, maddening in its scope and disunity, revelatory in its accidental harmonies which span thousands of years. To write or produce a book is to participate in this conversation. Yet the intensity and concomitance of this chaos and order makes walking through a bookstore or library exhausting, humiliating. A book, then, is a kind of sacrifice—because it is painful and costly to enter this conversation. The cost for a person who’s serious about books is that they can no longer speak with any grace during all those other conversations called “conversations” in day-to-day life: niceties, weather observations, constant nervous check-ins about the body and the mind and the state of the nation. Why? Because a great book is like a crystal whose form shapes great questions. In order to form these crystals, an author must permit themselves only the cold and arid air of solitude, distance, erudition, and honesty. Being open to this air requires a distance from one’s friends, one’s family. A book requires one’s blood.

I’m thirty-one. As I type this sentence, I’m looking at the rows of books I own. Despite making and spending money, I don’t like the sound of that: that these are my books. They’re not mine. They’re just temporarily living with me. And they do that: they live. They live because a book testifies to life. Not to the bland, back-of-the-cover-copy version of life, with its glib emphasis on the human and the joys and sorrows of social existence. A book testifies to the wider, stranger, more terrifying and fulfilling life we know when we are most inexplicable to ourselves. I’ve known this wider life when I’ve experienced any love whose existence I couldn’t fit into my vision of the order or disorder of things. Every gift points at this wider life; I’m sure of this. And I’m sure that each book is a gift.