Luis Panini is one of the most talented writers you’ve never heard of. With writing that recalls the best of Franz Kafka, Lydia Davis, David Foster Wallace, and Julio Cortázar, it is a regret that his writing can not be read in English (until now! see below). I recently sat in on a class at CalArts where he was a special guest in my friend Laura Vena’s class on Latin American literature, and it was a huge pleasure to hear him talk about his writing and thought processes. Laura Vena translated a few of his short stories (or fragments) into English, the results of which can be found below, and so I’m hugely happy and excited to share this interview here and debut these new translations of his work into English.

Luis Panini is one of the most talented writers you’ve never heard of. With writing that recalls the best of Franz Kafka, Lydia Davis, David Foster Wallace, and Julio Cortázar, it is a regret that his writing can not be read in English (until now! see below). I recently sat in on a class at CalArts where he was a special guest in my friend Laura Vena’s class on Latin American literature, and it was a huge pleasure to hear him talk about his writing and thought processes. Laura Vena translated a few of his short stories (or fragments) into English, the results of which can be found below, and so I’m hugely happy and excited to share this interview here and debut these new translations of his work into English.

Janice Lee: In your other life, you’re an architect and furniture designer. I’m interested in how this work and mode of thinking influences your stories. For example, the preciseness of your language, the constructedness of your stories as rigid and stable structures, your attention to spatial details and spatial relationships, and the existence of people and objects in physical environments rather than in relation to each other.

Luis Panini: My academic background has not only influenced the way in which I think about stories before I actually write them but also it has made me think about overall structures when I am constructing (not writing) a book, whether is a collection of short fiction, a novel, a book of poems or some piece of writing that does not necessarily falls into these ankylosing categories. Spatial awareness is very important for me since it is ultimately where the “game is played” and this is why I frequently try to inject some sort of symbolic meaning to both, the spaces my characters inhabit and the objects they come in contact with. In a way, what I am trying to accomplish is to integrate these “architectural objects” into the narrative in such a way that these become as important as the characters or the story itself. It is about translating the mere functionality of a space or an object into an emotional component in the writing process or how this space or object is acknowledged and assimilated by the reader. Duchamp’s “Fountain” comes to mind. He managed to transform a simple urinal into an object charged with many layers of meaning by placing it within the confines of a “sacred space.” Outside the museum, Duchamp’s piece is nothing but a urinal. Inside the museum is everything but a urinal because the reading conditions of this object have been transgressed. This is the sort of relationships I like to establish between my characters and the space they move about.

JL: You’ve described your stories as vignettes or fragments, and I think they operate in this way, but too, at the same time, they seem like such self-contained and intentionally built structures that do have set boundaries. Can you talk a bit more about the general shape of your individual stories?

LP: I did refer to those texts (the ones collected in my second book) as vignettes or fragments because that is truly what these are. They are absolutely self-contained pieces of writing. I like to think that the most interesting building block in writing is not the sentence, the paragraph, the chapter, etc. but the fragment, because a fragment does not require a beginning or an end, it does not need to tell a whole story to work, it does not have to acknowledge the fragment that precedes it or follows it and I find this to be truly liberating, a sense that I do not get when I take a different approach. About a year or two ago I finished writing a book that deals with memory and it is comprised of more than one hundred fragments. There are two versions of that book. In one version the fragments follow a chronological order of events and in the other version the fragments appear in the order in which they were written, the order in which I remembered a loved one who died recently. I chose to write about that story through fragments because in a way I wanted to emulate the mechanisms of memory and a fragmentary approach made perfect sense since I could experiment with the elasticity of the overall structure (or lack of one) by allowing a virtually infinite number of permutations. This also allowed me to set very strict boundaries on a fragment bases that I had to respect as I was writing each line. Every time I deviated in any way from those boundaries, the fragment did not work. It felt like an ill-conceived part of a whole. Through this method of writing I learned about the shape of not just individual stories but also how these can be connected in a book and how they interact among themselves by borrowing, cannibalizing from each other, etc. A book composed of fragments can be dozens of different books, only limited by the sequence you end up choosing.

JL: I know you are a Béla Tarr fan too, and I find that there are some resonances in your work with Tarr’s fans. For example, the focus in your stories is often on a person’s existence in a space or situation, and the story settles in on the details of the environment, constructing a scene that becomes a sort of story, rather than a story that is based on action and resolution. This reminds me of the indifference of the camera in Tarr’s films too, where often the setting is there before a character enters, and remains there after the character is gone. What are your thoughts on this observation?

LP: Sometimes I think that filmmakers are the ones who truly influence my creative process and writing methods, much more than literature in general or specific writers and books, and this has nothing to do with the fact that I live in Los Angeles, a city in which if you mention that you are a writer most people immediately ask you what screenplays have you written. Béla Tarr is one of these auteurs (I can’t tell you how much I enjoyed seeing that old man peeling potatoes in “The Turin Horse”), but also I am fascinated with the way other directors choose to tell stories, like Michael Haneke, Yorgos Lanthimos, and my personal favorite Ruben Östlund. I am not trying to say that my literary work has a cinematic quality or that it could easily be translated onto the screen, but this element becomes quite obvious since I tend to favor heterodiegetic narrators in most of my texts. I like to take it to the extreme, turning them into machine-like narrators which can be perceived as actual cameras panning through multiple rooms in a residence to create some sort of long shot composed by zoom-ins, abrupt cuts, blurs, etc. My vignette titled “The Event” is an example of this. After the character has “disappeared” in a very tragic way the camera goes back into the apartment where it all began and stays in recording mode to capture the solitude of the space, which to me is far more important than the demise of the actual character. In another vignette the narrator also acts as a camera that moves inside of a mansion to capture many of the possessions of a lonely man dying of complications related to an immunological disease. I was not interested in that man’s story specifically, but in how I could construct one by describing the pieces of furniture and ornaments he owns, the art hanging on his walls, and the materials and finishes of his home. I guess by doing this I am trying to illustrate some sort of terror that sometimes keeps me awake at night, the fact that after one dies everything else remains in its place, unaltered, because we are that insignificant. And it is this sense of pervasive malaise what informs most of my writing.

JL: I’m affected deeply by level of compassion and human dignity present in Tarr’s fans. On this subject, Andras Balint Kovacs writes:

“The man, whose philosophy despises ‘humanist’ feelings like compassion and pity, suddenly and certainly unwillingly, manifests the deepest compassion for a helpless living being, a beaten horse. This event, says Krasznahorkai, is ‘the flashing recognition of a tragic error: after such a long and painful combat, this time it was Nietzsche’s persona who said no to Nietzsche’s thoughts that are particularly infernal in their consequences.’ This is the example which leads to a conclusion about the universality of this feeling: ‘if not today, then tomorrow… or ten, or thirty years from now. At the latest, in Turin.’ … an attitude or an approach to human conditions, which Tarr fundamentally shares with Krasznahorkai… Both authors have a fundamentally compassionate attitude toward human helplessness and suffering in whatever situation it may manifest itself, and of whatever antecedent it may be the result.”

In Tarr films, compassion can exist without moral judgment, or, in other words, “In the Tarr films human dignity is not based on morality. It is based on the fact that in spite of their absolutely hopeless and desperate situations the characters remain what they are, however low what they are brings them.”

This simultaneous closeness and distancing, this empathy is ever-present in your stories for me too. For example, in “Mathematical Certainty,” there is a deep care in the description of the hat, but also in the generous curiosity afforded to the man with the brain tumor. I also recently heard Lydia Davis talk about description, and said something like, “In order to describe something, you have to love it. Even if it’s ugly, like an old shoe, you have to love it in a way to really describe it.” The preciseness of your language and the kind of curiosity afforded by such a detail as the length between the interior wall of the hat and the tumor, seems like a generous gesture in a way. What are your thoughts?

LP: I believe empathy and compassion is what drove me to write the vignettes included in my second book, as strange as that may sound given the dark nature of the overall subject matter of those texts, which is ill will. In fact, I can pinpoint the exact moment that acted as the catalyst. Back in 2006 there was a terrible brush fire, which consumed an enormous area near Los Angeles. For some reason that I yet have to comprehend a news show chose to broadcast a recording with no “viewer discretion advised” warning beforehand. I saw the body of a fallen hare partly carbonized. It was still moving, shaking the rear legs, convulsing, agonizing. And it affected me so much because animal suffering is something I simply cannot deal with. So this visceral reaction prompted me to explore this feeling in different ways, in fact so many that soon became a book about ill will. Ill will towards animals, patients with terminal diseases, sexual partners, art, even towards the reader. The main character in “Mathematical Certainty” is a man who soon will die of a brain tumor he has chosen not to have surgically removed. Instead, he decides to buy a white hat to conceal, maybe in an unconscious way, this organic tissue developing inside of him. Growing up in a predominantly catholic environment I heard many people say that the real reason why a man or a woman got cancer was the result of divine punishment, as if sinful behavior (whatever that means) could trigger it. So, in a way, that particular vignette is about religious ill will, the supposed shame caused by the disease, thus the comparison between the hat and a crown of thorns. Again, I was not too interested in the life of this character, but in presenting a juxtaposition of elements, such as a man fully dressed in white with something truly dark growing inside of his skull, and more so in determining the distance between the interior wall of the hat and the tumor, because those particularities or insignificances are what fuel my desire to write. I don’t want to write about the victims of a serial killer or the reasoning behind his actions, instead I want to write about the way in which this terrible person peels potatoes.

JL: The last time I saw you, you mentioned an anecdote about reading from your work with another Mexican writers, and being accused of not being “Mexican” enough in your writing. Can you speak a little bit to this and the identity expectations at large associated with being a writer from a certain category, identity, race, gender, etc.?

LP: I have never been too keen on assigning locality to my work. Unless it is absolutely necessary for the story, I prefer not to mention cities, countries, currency, etc. that could trigger preconceived notions while someone reads one of my stories or novels. Nameless entities give me the opportunity to engage the reader in a different way since the lack of geographical specificity will ultimately force him/her to build one, whichever best fits his/her imagination. In fact, two years ago I finished writing a novel that, at least in my mind, takes place in Brasilia, I am not sure why, perhaps it has to do with the fact that Brasilia was one of the cities I read about the most while I was studying Architecture and I wanted to replicate some of its urban elements in my novel. Most of my stories can take place in many different corners of the world. I truly do not see the need to couple them with recognizable places. That anecdote you are referring to happened a couple of years ago. I read in public Mathematical Certainty and by the end there was an eerie silence. If memory serves me well, I believe I heard a woman coughing. It was that quiet. Then, another writer read a story about a man wearing a pair of old and dusty boots, walking on a dry piece of land with scarce vegetation; tumbleweeds were rolling in the background. And this man was searching for a lost love, a woman he had met several decades before but had not seen during all of this time, I do not remember why. The audience went absolutely mad. Many of its members got up to give the writer a standing ovation. And he was smiling, he was very proud of his work. And I was smiling too because I was happy for him, but I was also very happy to have read Mathematical Certainty because I got to tell a story I still believe is interesting, at least to me. During the Q&A, a member of the audience accused me of “not being Mexican enough” (he knew I no longer lived in Mexico, it was in the bio that was handed out), as if Mexican Literature could be reduced to a certain number of topics and literary formulas to tell any story. He also mentioned that my story had no “ending” and was inferior to the other one because in that other one “the guy got the girl”, as if some sort of redeeming quality must be integrated into any successful piece of writing. To this day that comment puzzles me because sometimes it makes me question myself about what is expected of me as a Mexican/American author? In any case I like to think that nothing is expected of me. Many authors write about their roots, their people, identity, the social and political environments that rule the place where they were born, and there is nothing wrong with that, but I consciously choose not to write about those topics simply because I am not interested in them.

JL: Who are some other writers you’re reading now that you are particularly excited about?

• Hungarian author László Krasznahorkai is the first that comes to mind. I have read most of his work available in English and Spanish. A couple of months ago I read the beginning of Seiobo There Below, his latest novel to be translated, and I was mesmerized by it, so I just bought it as part of my “Christmas Book Haul.” Those were, perhaps, the most beautiful lines I have ever read. Krasznahorkai is, by far, my favorite writer at the moment.

• Hungarian author László Krasznahorkai is the first that comes to mind. I have read most of his work available in English and Spanish. A couple of months ago I read the beginning of Seiobo There Below, his latest novel to be translated, and I was mesmerized by it, so I just bought it as part of my “Christmas Book Haul.” Those were, perhaps, the most beautiful lines I have ever read. Krasznahorkai is, by far, my favorite writer at the moment.

• Another great author I have read recently, also from Hungary, is Péter Nádas. His Parallel Stories is a massive +1,100-page novel, but it is incredibly rewarding (for the most part).

• I am currently reading a very peculiar book titled Vampyroteuthis Infernalis, written by Vilém Flusser and Louis Bec. It is some kind of philosophical/biological treatise about a very odd cephalopod, the Vampire Squid, so odd in fact that it is the only animal not extinct in a unique order: Vampyromorphida. All I can say about it is that I am really enjoying it.

• Also, I just got the 2-volume Everyman’s Library edition of The Transylvanian Trilogy, by Miklós Bánffy, yet another Hungarian author, whom I am particularly excited to read. It is supposed to be an epic tale of twisted aristocrats pre World War I, at least the first part (think Downton Abbey season one, just set in the Austro-Hungarian Empire right before the assassination of the Archduke).

• The Spheres trilogy: Bubbles, Globes, Foam (I believe only the first volume is available in English), written by German philosopher Peter Sloterdijk, is another one of my recent reads that I enjoyed immensely. This man’s erudition just baffles me. The trilogy is divided according to the scale of the interconnectivity of the micro and macro spaces Sloterdijk is exploring to tell the history of humanity through a multifocal point of view.

• One of the best novels I’ve read in 2013 was Thomas Pynchon’s Bleeding Edge. I thought the story was brilliant and kept me engrossed from cover to cover. Very rarely do I laugh out loud while reading, but this book managed to do it. Nobody else writes dialogue like Pynchon.

• One of the best novels I’ve read in 2013 was Thomas Pynchon’s Bleeding Edge. I thought the story was brilliant and kept me engrossed from cover to cover. Very rarely do I laugh out loud while reading, but this book managed to do it. Nobody else writes dialogue like Pynchon.

• Every year, since 2007, I travel to Mexico to visit the International Book Fair in the city of Guadalajara, Jalisco, where I purchase most of what I read in Spanish. Back in 2012 I was looking for La experiencia dramática, Sergio Chejfec’s latest novel, at the “Argentinian Books in Mexico” stand. I could not find it. The man in charge said to me “if you love Chejfec you should check out the work of Néstor Sánchez”, another Argentinian author. So I did. I purchased three of his books, which I read recently, and he was so right. Sánchez wrote some of the best books I have ever read in Spanish and he has to be the best-kept secret of Argentinian Literature, even ten years after his death. I truly hope his work will soon be available in English. And on that note, I just bought Modo linterna, a book of short stories by Sergio Chejfec, who is simply one of the greatest authors walking on Earth. A couple of his books are available in English. I highly recommend to everyone My Two Worlds. Everything around me disappeared while I was reading it. It is that good.

• And then there is Mario Bellatin, whom I have been reading with religious devotion for the last 15 years and continue to do so. I just finished El libro uruguayo de los muertos, one if his finest books to date. He is one of the most engaging, mysterious, disturbing, and original authors working today, not just in Mexico, but all over the world. Bellatin truly defies what literature can be by constantly refining and reinventing his own writing methods. He allows his readers to construct mental bridges between his books, to link and decipher their cryptic contents so they can gain full access to one of the strangest, most hermetic, self-referential (or not) literary universes populated by his very own personal mythology. A great starting point is Shiki Nagaoka: A Nose for Fiction, which is available in English.

• And these are some of the books I am very excited to read in 2014:

• And these are some of the books I am very excited to read in 2014:

• Mathématique, by French author Jacques Roubaud, my favorite member of Oulipo. It is the third installment in his proustian-size project he started with The Great Fire of London and continued with The Loop.

• Mircea Cărtărescu’s Blinding Volume 1, which is supposed to be some sort of delirious memoir plagued with fictional elements and one of the best books ever written by a Rumanian author.

• The Discovery of Heaven, by the Dutch writer Harry Mulisch. A couple of months ago I visited the Netherlands and one of my brothers in law, who lives in Olst-Wijhe, took me to the house that Mulisch used as the inspiration for the main architectural setting in his most famous work. This, of course, triggered my curiosity and prompted me to buy a copy of the novel.

• Perhaps I am most excited to read Reiner Stach’s biography of Franz Kafka, comprised by three volumes, although only two have been published in German. Princeton University Press has also published both in English.

• Also looking forward to reading the collection of stories Autobiography of a Corpse, by the Russian author Sigizmund Krzhizhanovsky, which just came out a couple of weeks ago in English. I have never read anything by him, but I understand he is one of the masters of the absurd and dark humor.

• Finally, two books coming out soon that I can’t wait to read by American authors are Can’t and Won’t, by Lydia Davis, and Leaving the Sea, by Ben Marcus. I am always amazed by the attention each of them pays to every single sentence they produce, like Gary Lutz or David Foster Wallace. Reading any of these authors is like venturing into something similar to a state of hypnosis.

***

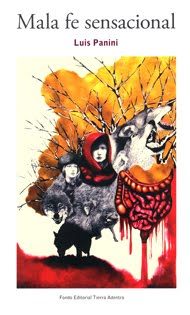

Luis Panini was born in Monterrey, Mexico in 1978. He holds a Bachelor of Architecture degree from the Autonomous University of Nuevo León as well as a Master of Architecture degree from the University of Kentucky. He is the founder of PeRiOdIcA:, a furniture design studio. He has published two books of short fiction, Terrible anatómica (2009) and Mala fe sensacional (2010), and his work has been included in numerous fiction anthologies and magazines. A book of poems and his first novel will be published in 2014.

Luis Panini was born in Monterrey, Mexico in 1978. He holds a Bachelor of Architecture degree from the Autonomous University of Nuevo León as well as a Master of Architecture degree from the University of Kentucky. He is the founder of PeRiOdIcA:, a furniture design studio. He has published two books of short fiction, Terrible anatómica (2009) and Mala fe sensacional (2010), and his work has been included in numerous fiction anthologies and magazines. A book of poems and his first novel will be published in 2014.

***

Selection of texts from the book Mala fe sensacional / Ill Will Sensational

Dos buitres

En realidad la composición de la imagen fotográfica, galardonada con un Pulitzer en 1994, es muy sencilla, tanto que cualquier especulación u opinión de tipo subjetivo resultaría fuera de lugar. Sería ridículo interpretarla como algo distinto de lo que es: una niña y un buitre esperando a que muera para devorarla, eso es todo. Una situación que encuentra en su apática simplicidad la grandiosidad que sólo los hechos más condenables ameritan. La pequeña aparece en primer plano sobre una superficie de tierra suelta, rodeada de hierba quemada por el sol sudanés. Está desnuda, tumbada en el suelo, el cuerpo demacrado por la desnutrición, a punto de sucumbir ante la falta de líquidos y alimento. El cuello lo tiene decorado con un collar blanco hecho de huesos o piedras, también lleva una pulsera del mismo color. No se le ve la cara porque mira hacia el suelo y consolida la poca energía que le queda en los codos para sostenerse y seguir arrastrándose. En segundo plano está el buitre con sus alas replegadas, las garras firmes sobre el terreno. Es muy probable que se trate de un alimocho sombrío, también conocido por su nombre científico como Necrosyrtes monachus, o bien puede que sea un buitre cabeciblanco, Trigonoceps occipitalis, ambas especies nativas de esta región. El pajarraco tiene clavada la mirada sobre la espalda de la esquelética niña; espera con inmutable paciencia su muerte para picotearle la escasa carne que aún le envuelve los huesos. El instinto le dicta que sería inapropiado arrojarse sobre el cuerpo de la pequeña mientras ésta lucha por eludir su inevitable extinción.

Two Vultures

Translated by Laura Vena

The composition of the photograph –awarded a Pulitzer in 1994– is, in fact, so simple that any speculation or opinion of a subjective nature would be out of place. It would be ridiculous to interpret it as anything other than what it is: a girl and a vulture waiting for her to die in order to devour her, that’s all. A situation in which simplistic apathy manages to achieve the type of grandeur that can only be found in the most deplorable acts. The little girl appears in the foreground atop a surface of loose soil, surrounded by grass burned by the Sudanese sun. She is naked, lying on the ground, her body emaciated by malnutrition, about to succumb due to a lack of fluids and nourishment. Her neck is decorated with a white collar made of bones or stone, and she wears a bracelet of the same color. You can’t see her face because she’s looking down, consolidating what little energy she has left in her elbows to hold herself up and continue crawling. The vulture appears in the background with its wings folded, its claws firmly gripping the ground. It’s very likely that it is a Hooded Vulture, also known by its scientific name, Necrosyrtes monachus, or it may be a White-headed Vulture, Trigonoceps occipitalis, both species native to the region. The buzzard has nailed its gaze to the back of the small skeletal girl; waiting with enduring patience for her death to then peck the little bit of flesh that still envelops the bones. Instinct dictates that it would be inappropriate to throw itself over her body while she struggles to elude her inevitable extinction.

***

Certeza matemática

Para encontrar el departamento de caballeros, él toma como guía la ruta señalada en los letreros iluminados que cuelgan del plafón. Lleva puesto un traje blanco. La camisa, los zapatos, el cinturón y la corbata son del mismo color. Tiene un tumor maligno en la cabeza, del tamaño de un chícharo, alojado entre la glándula pituitaria y el hipotálamo. Se lo diagnosticaron hace un par de semanas, pero eligió no someterse al procedimiento quirúrgico recomendado por su oncólogo para extirpárselo. Le pronosticaron seis meses de vida, quizá ocho, pero podrían ser dos, no es fácil determinarlo, le confesó el médico. En la sección de caballeros le llama la atención un sombrero que decora la cabeza de un maniquí en el interior de un mostrador de cristal. Le pide a una de las empleadas que por favor se lo muestre. La señorita lo toma con delicadeza y se lo ofrece al hombre del tumor, quien se lo prueba con sumo cuidado, como si se tratara de una corona de espinas. El sombrero, estilo Fedora, es de fieltro de lana blanco y corona de forma triangular. Tiene un listón de seda, también blanco, que rodea el perímetro donde la corona y el ala se intersectan. El hombre, de pie frente a un espejo situado sobre el mostrador, ajusta la posición del sombrero hasta quedar satisfecho y decide comprarlo. Le pide a la señorita que le retire la etiqueta porque quiere dejárselo puesto. Si pudiera dibujarse una línea imaginaria entre la pared interior del sombrero y el tumor maligno, ésta sería de aproximadamente siete centímetros de longitud.

Mathematical Certainty

Translated by Laura Vena

To find the men’s department, he uses the path designated by the illuminated signs hanging from the ceiling as a guide. He wears a white suit. The shirt, shoes, belt and tie are the same color. He has a malignant brain tumor the size of a pea, lodged between the pituitary gland and hypothalamus. It was diagnosed a couple weeks ago, but he chose not to undergo the surgical procedure recommended by his oncologist to remove it. They predicted he had six months left to live, perhaps eight, but it could be two, it isn’t easy to determine, the doctor confessed to him. In the men’s section his attention is drawn to a hat decorating a mannequin head inside a glass case. He asks one of the employees to please show it to him. The young lady picks it up delicately and offers it to the man with the tumor who tries it on with extreme care, as if it were a crown of thorns. The hat, a Fedora, is made of white wool felt and features a triangular shaped crown. It has a silk band, also white, around the perimeter where the crown and wing intersect. The man, standing in front of a mirror placed on the counter, adjusts the position of the hat until he’s satisfied and decides to buy it. He asks the young woman if she would remove the price tag because he wants to wear it out. If an imaginary line could be drawn between the interior wall of the hat and the malignant tumor, it would be approximately three inches in length.

***

El evento

Al introducir la llave en la cerradura de la puerta de su apartamento, antes de emprender su acostumbrada visita semanal al supermercado, la anciana no sabe que ésta es la última vez que lo hará. La llave gira en el interior del cerrojo hasta que el pestillo produce un sonido mecánico al encajarse en el muro. Levanta el canasto vacío del suelo y oprime el botón que llama al ascensor para que sus puertas se abran en el piso que habita. El interior huele a orina seca y está decorado con graffiti de color negro y rojo; dibujos de genitales masculinos dominan la temática. Afuera la gente camina en las calles aprisa al asomarse las primeras gotas de lluvia, gente sin rostro, automática. Un perro anda en busca de algún lugar para resguardarse, le ladra a un automóvil que pasa junto a él y al cielo que ya parpadea con relámpagos. Ella espera a que el hombre del semáforo se ilumine antes de cruzar la avenida. Cuando la silueta se enciende, baja con cuidado del cordón de la acera hacia el asfalto de la calle y con el mismo cuidado sube a la del lado opuesto, justo antes de que una manada de coches se lance apenas la luz roja del semáforo le devuelva el turno a su compañera de color verde. Conoce el número de segundos en que la silueta del hombre permanece iluminada; un tropezón, un calambre en la pantorrilla, significaría su violenta e irremediable muerte, por eso acostumbra protegerse con la señal de la cruz antes de disponerse a cruzar, para que Dios remueva los obstáculos del asfalto que su visión cansada no le permite anticipar y para que sus débiles piernas no la traicionen con un espasmo en los músculos. Sobre la acera, una serie de tenderetes que ofrecen fragancias de moda y cintas piratas obligan al tráfico peatonal a convertirse en una masa apretada que trata de no aplastar con sus múltiples pisadas la mercancía desparramada en el suelo. La puerta principal del supermercado se abre para recibirla y por allí consigue desgajarse de la multitud. Pero algo sucede dentro, algo que hace retumbar al edificio hasta sus cimientos y despedaza los cristales de la fachada principal y que luego la muchedumbre, confundida debido al portentoso estruendo, le describe a los agentes de la policía como una fuerte explosión de gas natural, un terrorista suicida, la turbina que a un avión se le desprendió en pleno vuelo o un meteorito de malhadada trayectoria. Mientras paramédicos y samaritanos atienden y ayudan a los heridos, separan a los vivos de los muertos y embolsan lo que a primera vista puede reconocerse como restos humanos, en el interior del apartamento de la anciana un canario enjaulado dormita. Hay tres o cuatro vasos de vidrio sucios en el fregadero que planeaba lavar antes de irse a dormir. Un mantel de macramé, de incalculable valor sentimental, cubre la mesa del comedor. Sobre los burós de noche, junto a su cama, descansan un par de lámparas con flequillos de seda. En el recibidor se encuentran anclados a los muros una serie de anaqueles que decoró con su colección de figurillas de cerámica y porcelana: payasos de gesto melancólico ataviados con ropas de vagabundo.

The Event

Translated by Laura Vena

As she inserts the key in the lock of her apartment door, before setting off on her usual weekly visit to the supermarket, the elderly woman does not know that this is the last time she will do it. The key turns inside the lock until the bolt makes a mechanical sound as it sets into the frame. She lifts an empty basket from the floor and presses the button that calls the elevator so that its doors open up on the floor she inhabits. The interior smells of dried urine and is decorated with black and red graffiti; drawings of male genitalia dominate the theme. Outside, people walk in the streets with haste at the first sight of raindrops, faceless people, automatic people. A dog is looking for a spot to shelter himself, he barks at a car that passes by and at the sky that now flashes with lightning. She waits for the little traffic signal man to light up before crossing the street. When his silhouette lights up, she carefully steps down from the curb onto the asphalt and with the same care she ascends on the opposite side, just before a herd of cars is released as the red light turns the shift over to its green-colored companion. She knows the number of seconds that silhouetted man will remain illuminated; a stumble, a cramp in the calf would bring to her a violent and irremediable death, this is why she protects herself with the sign of the cross before preparing to set out for the other side of the street, so that God would remove obstacles from the asphalt that her tired vision wouldn’t let her anticipate and so that her weak legs would not betray her with a muscle spasm. On the sidewalk, a series of stalls offering designer fragrances and pirated DVDs force the pedestrian traffic to become a tight mass that tries not to crush the merchandise scattered over the ground under its multiple footsteps. The supermarket doors open to welcome her and she manages to break away from the crowd. But something happens inside, something that shakes the building to its foundation and shatters the windows of the main façade, which later the crowd, confused by the ominous roar, describes to police officers as a strong natural gas explosion, a suicide bomber, a turbine fallen from an airplane in flight or a meteorite with an unfortunate trajectory. While paramedics and good Samaritans attend to and help the wounded, separate the living from the dead, and recover what at first sight can be recognized as human remains, inside the elderly woman’s apartment a caged canary slumbers. There are three or four dirty glasses in the sink that she had planned to wash before bedtime. A macramé tablecloth of priceless sentimental value covers the dining table. A couple of silk-fringed lamps rest on the nightstands beside her bed. In the entrance hall there are a series of shelves anchored to the walls that she had decorated with her collection of ceramic and porcelain figurines: clowns with melancholic gestures dressed in vagrant’s clothes.

***

El tamaño de la familia

Tenía mucho tiempo de no ver a su hijo participar en un campeonato de lucha grecorromana. Prefería evitar esos enfrentamientos pues la alteraban sobremanera. La posibilidad de que el contrincante lo lastimara le impedía disfrutar del encuentro y siempre terminaba cubriéndose los ojos cuando veía que el rival apuntalaba a su hijo para que sus omóplatos hicieran contacto con la colchoneta y así vencerlo. Por lo general era el padre quien asistía a las contiendas, pero desde su inevitable deceso a causa de un cáncer pancreático que lo consumió en menos de tres meses, la madre era quien lo acompañaba a los gimnasios cuando se trataba de campeonatos estatales o quien volaba con él cuando el evento adquiría magnitud nacional, como en esta ocasión. Hacía más de cuatro años que no lo veía con el uniforme puesto. Los tirantes del maillot acentuaban la fortaleza de sus hombros y dejaban al descubierto la musculatura de su espalda, características en las que no había reparado debido a la imperante moda en la forma de vestir que los jóvenes habían favorecido en los últimos años al usar prendas de tallas mucho más amplias de las que requerían. Esta vez no se cubrió los ojos. Su destreza atlética la impresionó. Lo vio flexionar las rodillas, girar la cadera, aplicarle a sus adversarios rusas, lianas, turcas, tijeras y un suplé a su último rival que el público ovacionó con frenesí y por el que logró obtener la copa del campeonato. Cuando el árbitro lo declaró vencedor, él se apresuró hacia la butaca desde donde su madre había presenciado el evento. Al momento de abrazarla con su cuerpo todavía caliente y el cabello empapado de sudor, le tomó por sorpresa la volumetría de los genitales de su hijo contra su vientre, quien luego de unos segundos se despidió para ir a ducharse a las regaderas antes de que la ceremonia de premiación diera comienzo. Regresó vestido con un maillot diferente, de color blanco, que evidenciaba en mayor grado el abultamiento de su entrepierna. Ella lo contempló desde su asiento. Era el hombre de la familia.

The Family Size

Translated by Luis Panini

She had not seen her son competing in a Greco-Roman wrestling match in a very long time. She preferred to avoid such tournaments as these affected her greatly. The possibility that the opponent could hurt him prevented her from enjoying the match as she always ended up covering her eyes when the adversary pinned her son down so his shoulder blades would make contact with the mat to defeat him. It was usually his father who attended these events, but since his inevitable death due to a bout of pancreatic cancer that consumed him in less than three months, the mother accompanied her son to the gymnasiums when it came to state championships or flew with him when the event took on a national scale, as on this occasion. It had been more than four years since she last saw him in uniform. The straps of his wrestling singlet accentuated the strength of his shoulders and exposed the muscles of his back, features she had not noticed due to a prevailing fashion trend to wear clothing much larger than the required size that was favored by teenagers in recent years. Only this time she did not cover her eyes. His athletic dexterity impressed her. She saw him bending his knees, turning his hip, applying Russian ties, headlocks, reverse lifts, Half-Nelsons, and a highly praised suplex to his last rival for which he managed to get the championship cup. When the referee declared him the winner, he rushed to the spot where his mother had witnessed the match. As he hugged her, she felt that his body was still warm from the match and his hair was soaked in sweat. The size of her son’s genitals pressed against her abdomen took her by surprise. After a few seconds he said goodbye as he ran to the locker room to shower before the commencement of the awards ceremony. He returned wearing a different singlet, a white one that made his protruding crotch much more obvious. She stared at him from her seat. He was the man of the family.

Tags: bela tarr, Krasznahorkai, Luis Panini, Lydia Davis, Mala fe sensacional, Mario Bellatin, Mexican Literature, Miklós Bánffy, Thomas Pynchon

this is extremely very incredible

[…] Read the whole thing here! […]

[…] HTML Giant, una de las más prestigiadas páginas de literatura de Estados Unidos, acaba de publicar Luis Panini, autor de Mala fe sensacional, publicada en el Fondo Editorial Tierra Adentro en 2011. […]

I love this. Are any of his books being translated?

holy moly

macbook repair arlington heights

Interview With Luis Panini | HTMLGIANT