Author Spotlight

The David Shields Interview (Paperback Edition)

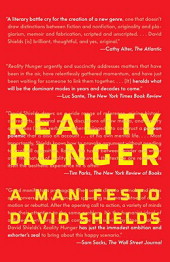

Flaubert claimed: “The value of a work of art can be measured by the harm spoken of it.” Reality Hunger, by David Shields, was one of the most controversial and talked-about books of 2010, reviewed nearly everywhere. Shields debated with journalists, writers, and artists such as Nicholson Baker, Simon Critchley, Leonard Lopate, John Cameron Mitchell, Rick Moody, Michael Silverblatt, Zadie Smith, DJ Spooky, Judith Thurman, and Simon Winchester. This past February saw the paperback release of Reality Hunger. Recently I met with Shields to analyze the polemics and decipher the carnage.

Flaubert claimed: “The value of a work of art can be measured by the harm spoken of it.” Reality Hunger, by David Shields, was one of the most controversial and talked-about books of 2010, reviewed nearly everywhere. Shields debated with journalists, writers, and artists such as Nicholson Baker, Simon Critchley, Leonard Lopate, John Cameron Mitchell, Rick Moody, Michael Silverblatt, Zadie Smith, DJ Spooky, Judith Thurman, and Simon Winchester. This past February saw the paperback release of Reality Hunger. Recently I met with Shields to analyze the polemics and decipher the carnage.

CALEB POWELL: The constructive response to Reality Hunger drowned, at times, amidst negative reviews. Walter Kirn said that he was “amused to see some of the hysterical reactions it’s provoked.”

DAVID SHIELDS: About negative reviews, the book is called a manifesto. It’s raison d’etre is to generate discussion. To provoke. I cannot object to any fiercely critical review. One reviewer said, “The discussion surrounding the book is more interesting than the book itself.” Well, what generated the discussion? My book.

CP: In their reviews…James Woods defended the traditional novel, and Michiko Kakutuni attacked.

DS: Neither of them talked about the book, they just mention it in passing. They are total spear carriers for conventional fiction…neither remotely engage with the argument. They mulch in a kind of drive by…Woods said something like…it’s good to be reminded of these arguments but Shields needs to define his terms better. Michiko called it “deeply nihilistic,” that’s so…

CP: It’s not the sharpest comment…it reads as hyperbole. I mean, you say the novel is worthless, but you praise a lot of art.

DS: She…and Woods, they are the megaphones of conventional fiction. The New York Times and The New Yorker, highly venerable institutions, whatever…they articulate nineteenth century conventional fiction…are you a Franzen fan?

CP: I’m Switzerland. But Franzen was friends with David Foster Wallace, and they both have third person authorial presence.

DS: I know what you mean. That heavy breathing.

CP: One blog put Freedom and Reality Hunger side by side as “the books of the year.”

DS: I think the blog goes on to say that basically you’ve got to choose. You can’t like both. I think that’s true. The 19th century—“Tolstoy of the digital age” – there can be no such thing. Or the other way forward to the 21st century: the Danger Mouse of the digital age.

CP: You say citation domesticates the writing. I say that quotation adds context, guides the curious.

DS: When one cites within a work of nonfiction, one turns it into a work of journalism or scholarship…we thereby refuse it entry into the realm of sublime literary art. I wanted the reader of Reality Hunger, halfway through the work, to say, hey, this work is full of passages from other people. I was hoping readers would Google these passages. I did not want to take credit for what Vivian Gornick or John D’Agata or Lauren Slater said. The book is an argument about provenance of genre; it was crucial that provenance extend to quotation as well.

CP: Google? David Foster Wallace wrote, in the essay on Roger Federer, “It’s all just a Google search away. Knock yourself out.” The writer earns authority by doing research…not by sending the reader to the library or computer.

DS: All Wallace is saying is that there’s this hilarious convention of middle-brow magazine journalism that, two/fifths through a piece, you have to give this painfully boring paragraph about where he was born, what school he went to.

CP: Exposition can be tedious.

DS: That essay on Federer is gorgeous: Wallace is making a connection between the perfection of Federer’s body and the horror-show of a little boy’s cancer. Wallace is saying that whatever “god” created existence and the perfection of Federer also created a kid who has cancer at age eight. Whatever entity created genius also created madness. Deal with that. It’s an oblique suicide note on Wallace’s part. He’s saying he has extraordinary intelligence and one self-punishing brain. He’s trying to say, “How am I going to solve this?” It wasn’t written that long before his suicide.

CP: You quote Wallace…that only art can “construct a bridge across the abyss of human loneliness.” To me, that relates to one of the three epigraphs of Reality Hunger, the one by Graham Greene: “When we are not certain we are alive.” Wallace wasn’t certain, yet he couldn’t live. Art couldn’t assuage his loneliness, despite his success.

DS: I’m not sure where you’re going. Art saves nobody. Neither does anything else.

CP: He recognized that only art could keep him from suicide; I’m not sure if that’s the correct interpretation.

DS: It is, actually.

CP: Art failed. There are so many people that need certainty.

DS: I see what you mean. That certainty saves them. They’re not great artists, though.

CP: My anti-Google aesthetic is minor compared to my, er…objections regarding your take on Frey. You can’t make yourself more tragic, more heroic,comic, or sympathetic; Frey did that. On purpose. Why defend him?

DS: I would never defend Frey per se; he’s not a good writer. But I want to say the invective that greeted Frey is terribly telling regarding how utterly confused we are about what’s real and what’s fiction…and also what the nature of the essayistic memoir has been since the beginning of recorded civilization. From the generals’ made-up speeches in Thucydides’ History of the Peloponnesian War to the dialogues of Edmond Gosse’s Father and Sons to Orwell’s “Such, Such Were the Joys” to de Quincey’s faux recovery in Confessions of an English Opium Eater: every essayist who has written a book length work has taken enormous liberties with the so-called truth. Memory is by its very nature a dream machine. Composition is a fiction-making operation. At its very best, essay confronts the nature of memory and the working of consciousness. I’m trying to reframe nonfiction upward as art.

CP: I think many readers already consider nonfiction art. But Frey went beyond embellishment, whereas Orwell did not.

DS: I got a “thank you” email from Frey.

CP: Did you save it?

DS: I may have.

CP: What did he say?

DS: He said, “Thank you; you’re the first person who got it.”

CP: That speaks well of his character. You wrote that he willfully performed hari kari when the culture beckoned.

DS: I don’t know whether he read the chapter partially about him, or parts of it, or whether he read the whole book or not, but I would imagine he liked the emphasis I placed on his being used as a scapegoat for the culture’s sins and the culture’s misunderstandings. I don’t admire or like his work, but I do think the culture tried to use him to get well, to cover the inconsistencies with fake-glue.

CP: You deride the novel as commercial, as entertainment. Your argument applies to horror or romance, but not to literary fiction.

DS: That’s not what I’m saying. It has nothing to do with sales or commercialism. It has to do with the motor of plot. The essential impulse of the novel is to tell a story. The essay’s impulse is to think hard about something. I’m a thousand times more interested in the latter.

CP: No no…I get that. I like what you like; I question your dislikes. Your reasons apply only to bad fiction. From passage 609 in Reality Hunger: “Onecould say that fiction, metaphorically, is a pursuit of knowledge, but ultimately it’s a form of entertainment.” Not with good fiction.

DS: I want simultaneously a more modest and more ambitious art. I want it to be on a scale that I believe in. After Sassure – language, after Heissenberg – perspective, after Wittgenstein – language, after Levi-Strauss – perspective, I can no longer believe that person X can gain access to the mind of person A through K. He can’t. He can gain partial access to his own mind and, granting his own subjectivity, he can then think about himself and the world, but he has to first grant the radical subjectivity of his analysis. Once he does that, and grants the necessary “modesty” and limit of what he’s doing, he can do something immensely ambitious. He can’t create a 3rd person novel full of plot and character and setting and “psychology” per Freud. I don’t believe it, and if he is a thinking and in any way contemporary person, he doesn’t believe it, and if he doesn’t believe it and is doing this, he’s writing in serious bad faith.

CP: The modern novel diverges considerably from the nineteenth century novel. The economy of story, technological vocabulary, war, history, et al, the entire landscape and subject matter have all evolved.

DS: No kidding. The novel of 2011 may be nominally different from the novel of 1878, but the elements are the same. Glacial plot that violates the speed and pace of contemporary life. An understanding of character that derives entirely from Freud rather than from contemporary cognitive science. A devotion to coherence that suggests god is in heaven and the world makes sense. An immersion in setting that is contradicted by how we live our lives. To the degree that contemporary work violates these antiquated desiderata, I tend to be somewhat interested in it, but the genre-obliterating essay does this as well or better than most novels, even postmodern ones, which are still to my ear circling the drain of useless narrative.

CP: Yes, but bad novels are easy targets. You often talk about anti-novels, but let’s just call anti-novels good novels.

DS: Of course. I love a lot of novels. I’ve read them. I love In Search of Lost Time, Moby-Dick, Tristram Shandy. I like Elizabeth Costello, Barry Hannah’s Boomerang, David Markson. None of them are novelly novels. I’m talking not about how great Anna Karennina is. Obviously, it’s incredibly great. I’m talking about the kind of book that we can write now in good faith.

CP: But what does that have to do with “reality?” Is your book about your personal obsession with “reality” or society’s obsession? Or both?

DS: Neither. It’s about the fact I was driving around in a car today and Oliver Twist was on the radio for some reason. My visceral reaction was, “Get me out of here. Get me to Spalding Gray. Get me to an individual human consciousness that I believe in and is wrestling with the world, not these pasteboard cut-out ‘characters,’ contrivances, etc.”

CP: Then I’d say your book is more Anti-Reality Hunger. Society escapes through pop art or media lobotomies, and you escape by art. But neither reaches “reality” at ground level. There’s no “reality” in your man Rothko’s vibrant orange quadrilaterals.

DS: The book is about art that strives to have as thin a membrane as possible between life and art. Kafka: “A book should be an axe to break the frozen sea within us.” To me, in our highly artificial culture, more fiction can’t do that. It’s only more bubble-wrap. The work that can do that, for me, is work that aims to teach us how to endure existence rather than helps us to escape it. Leonard Michaels, Shuffle. Sarah Manguso, The Guardians. Maggie Nelson, Bluets. Simon Gray, Smoking Diaries. Spalding Gray, Morning, Noon, and Night. V.S. Naipaul, A Way in the World. David Markson, This Is Not A Novel. Amy Fusselman, The Pharmacist’s Mate.

CP: I’ve no beefs, what you like is great…but you seek art, your book’s about “Killer-Art Hunger.” But I’ll contend that great fiction remains capable of touching the “real” while obliterating our internal frozen seas.

DS: This is the James Wood reaction: I’m just praising work that I like and that my next book might be about all the novels I like. I’m not sure what to say other than that that’s not what I’m saying. I specifically argue for obliterating distinctions between fiction and nonfiction, overturning laws regarding appropriation, and creating new forms for the 21st century. McEwan and Franzen don’t do that. In fifty years, I promise you, no one will be reading Ian McEwan and Jonathan Franzen. In twenty years no one will be reading books called Solar and Freedom. Art will have progressed so far beyond these extraordinarily antediluvian works that they will be viewed as escapees from 1890. I’m trying to get us to the next movement in literary art. I’m arguing for people who are already there, and I’m trying to get there myself. I’m trying to light the way, though sometimes the light at the end of the tunnel is just a piece of burning plastic.

***

Caleb Powell enjoys culture, travel, art, food, drink, conversation, friends and family, and he’s usually up for a beer. The Rumpus recently published a related David Shields interview here.

Tags: David Shields, reality hunger

I’m not sure if I’m supposed to be impressed or saddened at Shield’s complete inability to actually engage with any of his critics’s arguments…

In fifty years, I promise you, no one will be reading David Shields. In twenty years no one will be a reading book Reality Hunger.

I like his passion. I don’t think I would like to only read genre-busting essays.

I like his ideas about blurring the line between nonfiction and fiction, especially since “real life” seems obviously a series of creations and fictions. I feel like rappers rap about their lives and it is still art, not reportage. I feel like songwriters throughout the history of popular song wrote about their lives, and sometimes it’s exactly what happened and sometimes it’s been modified or added to. I love that, that’s exciting and fun.

I think reality in fiction, however it comes into it, and however much reality is a construct—nonetheless, it means something to say “reality,” even though it means a different thing to every person—that is exciting to me, and it is an investment. The author is invested. I as a reader can feel when there is investment, or more precisely, I think I feel it, which is wonderful. I like to feel like someone alive has tried to do something while alive. I don’t want to stare at word assemblages. I want there to be a dynamic between the author and the work, not just the happenstance of he or she having the name that is placed by that work. It can always be found, I think, but when it is striking, when I think I can feel it, I’m more excited.

I do kind of enjoy the “my sloppily argued, half-formed book inspired lots of people to talk about how bad it was! I generated a lot of discussion so the book was great!” line of thinking. Lot’s of poorly made things inspire discussion. Charlie Sheen’s stupid rants have caused a lot of discussion about drug habits and domestic violence, guess he is “winning” that one.

Re: the bubble wrap comment – Exactly!

It’s funny that Evan Lavendar-Smith is in the post right before this one because I know for a fact that Shields read a manuscript copy of ELS’s From Old Notebooks while he was working on Reality Hunger and the similarities between those two books are sometimes remarkable, although FON is like the thing that Shields is saying people should write but Shields doesn’t seem to actually have the balls or the brains to write himself.

*Lavender-Smith

I really do think you can defend those statements too plus many others (“every good story is at heart a comedy!” “every good story is a heart a tragedy!” etc. etc.)

But at some point, I just wonder what the point of saying “every story is a tragedy and a comedy and a myth and a form of realism and a form of surrealism and a fairy tale and a romance and a fantasy and a….”

whoops.

Stories, mythology… they work. Or can work. If they’re good, and you allow them to. Like how a snake will scare you even if you don’t know what a snake is. It’s old, storytelling is in our evolutionary biology. They can DO stuff to you (oh, the banality!) You can make people “think hard about stuff” as much as you want, fine, great, that’s necessary too. Other people will try to communicate on the snake level. These people will always be fighting. I’M BETTER AND YOU DON’T GET IT whackitywhackity.

I’ve read multiple interviews featuring Shields concerning “Reality Hunger”…to piggyback the first commenter, I find it frustrating and unrewarding to see his inability to engage the critics. It’s become a “copy and paste” response at this point. I actually enjoyed “Reality Hunger” for the ideas it suggested, yet I railed against it because, by the sheer construction of the book, he used the voices of other people far more articulate—and perhaps ballsy—than him. That’s my main beef for what it’s worth: right ideas (or at least ones worthy of debate), wrong spokesman at the podium.

i’ve been meaning to read this book. this interview made me want to even more.

“Yo, David, I tried to read your book, but just couldn’t do it.”

“What stopped you, man?”

“I just wasn’t entertained.”

“Such a pleb, Darian, such a pleb.”

CP: Then I’d say your book is more Anti-Reality Hunger. Society escapes through pop art or media lobotomies, and you escape by art. But neither reaches “reality” at ground level. This. And what is shield’s ‘reality,’ anyway, other than those mildly obnoxious lists of various works he keeps reciting, in place of definition or explication. The guy’s continual plaints against the various engines of conventionality that make up ‘the establishment’ seem more a tribute and endorsement of the baleful influence they exert over his own headspace than anything else. Bet the New Yorker and Jonathan Franzen and Woods/Kukatani wish they could corral and monopolize our consensus reality the way shield’s seems to think they do.

shield’s may rail against the cosy conventionality and trite characterization etc etc of the traditional novel but I’m glad to see he’s up for a bit of reductive pop psychologizing when it suits him – The federer piece ”is an oblique suicide note on Wallace’s part.” Horse’s ass

“He’s trying to say, “How am I going to solve this?” It wasn’t written that long before his suicide.”

Um, it was written 2 years before his suicide?

Shields seems less to be arguing for newer forms and more for ‘more geniuses’. Which is obviously what we all want/to be. Tessa Hadley is obviously far from a genius; with a few exceptions, there are probably almost no geniuses alive and writing today. Which doesn’t mean that Tessa Hadley’s work doesn’t have value, however small it may be.

[…] here). To coincide with the paperback release, we interviewed again, published 3 places online at HTML Giant, The Nervous Breakdown, The […]

[…] David Shields interview at HTML Giant. Paused when he said, “Art saves nobody. Neither does anything else.” […]

[Yawning] Is it over yet? There is a vast amount of the kind of writing that Shields hungers (yep) for, but it lies in the decrepit and impoverished ghetto of sci-fi/fantasy. Of course, very few of you aesthetes would even trouble yourselves to venture into such an area. Your loss, dearies.

Here’s one of the best. I’d love to see Shields take him on in debate.

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=PaWltr4aq4s

[…] the Cascades and threw down, building upon past quibbles, including interviews at Gulf Coast, HTML Giant, The Quarterly Conversation, and The Rumpus. Below, Shields finds ”Riding a Mower” […]

[…] into the Cascades and threw down and revisited differences, including interviews at Gulf Coast, HTML Giant, The Quarterly Conversation, and The Rumpus. The result was a book, announced 4/26/13 at Publishers […]

[…] threw down. The focus? Art vs. life. We revisited differences, including interviews at Gulf Coast, HTML Giant, The Quarterly Conversation, and The Rumpus. The result was announced 4/26/13 at Publishers […]