Ed vs. Yummy Fur by Brian Evenson

|

Ed vs. Yummy Fur

by Brian Evenson

Uncivilized Books, 2014

128 pages / $12.95 buy from Uncivilized Books

Rating: 10.0

|

A comic like Chester Brown’s Ed the Happy Clown isn’t one that’s easily discussed in polite company. It’s replete with scatology, hyper violence, and vomiting penises that look like Ronald Reagan. “[I]t’s hard to recommend Yummy Fur or Ed the Happy Clown to just anyone without offering a few caveats/qualifiers/warnings,” writes Brian Evenson. Nonetheless, the book is worth talking about—even more specifically, the journey from mini-comic to “a graphic-novel,” which is what Brian Evenson does with incisive detail in Ed vs. Yummy Fur or What Happens When a Serial Comic Becomes a Graphic Novel.

Brian Evenson is the perfect critic for the first installment of Uncivilized Books’s Critical Cartoons series (which also promises a book of criticism on Carl Barks’s work on Donald Duck comics—now available for preorder). As an author renowned for fiction and scholarship that bridges the gap between high- and low-brow cultures—after all this is the author of both Altmann’s Tongue and two Dead Space novelizations—Evenson lends a sense of legitimacy to Ed the Happy Clown as he meticulously examines Chester Brown’s work. Comic books—especially alternative mini-comics—are seldom the subject of serious literary criticism. I can go on and on about the injustices of the Ivory Tower-ensconced literary elite, but Evenson does this with far more aplomb throughout the work, deploying asides questioning the very nature of a “Graphic Novel” versus a comic book or “a graphic-novel” as well as quotations from other critical greats such as Douglas Wolk (although Evenson’s dissection of Wolk’s previous criticism of Chester Brown also becomes a point of contention in Ed Vs. Yummy Fur).

Brian Evenson contends that Chester Brown’s early work—albeit as crass as possible—is important because it redefines an entire genre of sequential art. Evenson places Brown within the same pantheon of deconstructive, comic book auteurs Grant Morrison and Alan Moore, but what’s even more notable than Evenson’s thesis is his own redefinition for what literary criticism can do. Criticism encourages a level of scrutiny that, ultimately, raises the original work up, regardless of its individual merit, and this is exactly what Evenson has done.

October 7th, 2014 / 12:00 pm

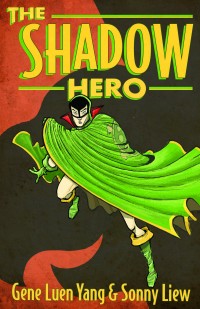

The Shadow Hero

|

The Shadow Hero

by Gene Luen Yang and Sonny Liew

First Second, 2014

176 pages / $17.99 buy from Amazon

Rating: 10.0

|

The Golden Age of comics in the 1940’s was thusly named for the influx in popularity of comics during that time. Publishers operating under a shotgun approach filled the market with every outlandish concept possible, hoping that they’d happen upon the next Superman or Captain America. Comic books have yet to regain that same level of popularity, but for those who frequent comic shops today, they can get a sense of the glut of new comic book characters that flooded the market in the beginning years of comics. The Green Turtle, a shirtless masked man with a cape sporting, well, a turtle shell was one of these transitory characters only lasting five printed issues. As is understandable, The Green Turtle has been forgotten by the mass culture and comic book obsessives alike, so why is he the subject of Gene Luen Yang’s new graphic novel?

Yang has established a strong oeuvre out of deconstructing the super hero mythos while blending it with his Chinese American heritage. His previous works, such as American Born Chinese and Boxers & Saints,combine Chinese mythology with American super hero action. In Boxers, the members of the Boxer Rebellion actually transform into superhuman warriors to defeat European missionaries and soldiers.

With this pedigree it’s no wonder that Yang and artist Sonny Liew found fruitful ground with The Green Turtle. Yang reveals that the hero was created by Chinese immigrant Chu Hing, and that it is conjectured that there was conflict with Hing and his publisher to make the Green Turtle Asian American—the basis of which lies in how Hing never drew The Green Turtle’s face, always obscuring it with a cape or an elbow or depicting him from behind, cape blowing in the wind. Also, Yang is perplexed by the use of racial stereotypes in Chu Hing’s artwork: “the impossibly slanted eyes, the buckteeth, the menacing Fu Manchu grins, the inexplicably pointed ears.” Yang asks whether this “ugly” depiction of The Green Turtle’s Japanese Axis enemies is Hing’s deconstructive commentary or pandering to American publishers, but the truth has been lost to history. As a result, Yang and Sonny Liew endeavored to create a new origin story for The Green Turtle in The Shadow Hero.

And what’s best about the book is that although the book does interrogate American racism—our hero calls the Dick Tracy-inspired Detective Lawful on calling the local crime syndicate “sneaky slant-eyed bastards”—the comic is much more than a simple criticism. What makes the comic a success is that it is a pure superhero origin story on top of being incisive cultural criticism. Yang and Liew follow the tropes of classic comics and create an action-filled book while also managing to make their readers think about race and culture, too. It’s the same genius we’ve seen in Yang’s work before. He uses stereotypes, but also pathos to show readers of all ethnicities what it means to be an outsider and what it means to be a hero.

August 21st, 2014 / 1:33 pm

Crystal Eaters

|

Crystal Eaters

by Shane Jones

Two Dollar Radio, 2014

172 pages / $16.00 buy from Two Dollar Radio or Amazon

Rating: 10.0

|

So my dad’s an alcoholic. (That’s really hard to admit. In fact, this is the first time I’ve typed it out, as I’m drafting.) He’s not a monster. He never beat me or did any physical harm to me. Just had outbursts and left me with daddy issues.

So the reason why I’m sharing this is because Shane Jones’s Crystal Eaters helped me come to terms with some of my childhood. If you haven’t heard the premise of the novel here’s the rub: people in this village have a crystal count. Crystals are depleted when people get hurt, age, etc. When you reach zero you’re dead. There’s a rumor that eating rare, black crystals will increase your life count, but it’s just a rumor. Black crystals do work like psychedelic drugs though. Basically, The Crystal Eaters is a novel of addiction. Everyone is addicted to something, whether it’s their self-image as a good parent, the idea of extending their life, or they’re addicted to imbibing the psychotropic black crystals, themselves.

So the son, Pants, of the main family in the novel feels guilty because his mom is dying and he can’t really do much about it because he’s in jail for tripping balls on black crystal in public. In prison, Pants realizes that he’s an addict because his parents beat him instead of not taking the time out to understand him. That means a fuckton to me because I’m an addict, too—only to porn and alcohol. What I’ve come to realize, and what Jones reinforces in his novel, is that my dad’s fucked-upness is not my fault. It’s just how his parents equipped him. “Her father had done the same to her, and so did Dad’s, and it worked, look at them, adjusted people. She didn’t necessarily believe what she thought, but her family history was stronger than her head.” As a result, the same becomes true for Pants. And even though he feels super guilty and blames himself for his mother and dad and little sister’s misfortunes, it’s not actually his fault.

“The universe is a system where children watch their parents die,” which I take to mean, the world just spins, the city grows, the sun gets hotter. Of course there’s the chance that we’ll become addicted, too: it’s a way for our bodies to heal—a coping mechanism. We just need to examine the source of our desires. Why do I need to write? Why do I need to live forever? Why do I need to drink until my brain shuts off? If we can get a grasp as to what our motivations are, maybe we can have an easier time through life. The best we can do is not to fixate on the counting down to zero—because we will all reach zero—and, if we’re lucky, touch a heart or two on the way. Read the novel. Maybe it will help you come to an important realization, too.

August 19th, 2014 / 12:00 pm

An Anonymous Email to Shane Jones

|

Crystal Eaters

by Shane Jones

Two Dollar Radio, 2014

172 pages / $16.00 buy from Amazon

|

Shane Jones,

To this day, I have still never seen these movies: Ray and Walk the Line. There are probably a few reasons why I haven’t, but one of the most important reasons concerns the fact that these movies were extremely hyped upon their release. Everyone was blowing their load. And by everyone, I guess I mean critics and my parents. So, I never saw them. I have a tendency to shy away from things that have received too much positive hype. I know myself and I can usually expect that I will be let down.

Crystal Eaters. I awaited the release of your book for months. And when it came out, I ordered it. And when it arrived at my house, I didn’t read it, at least not for a while. I wanted to pick it up and start it, but I kept seeing all of these intensely wordy and existential reviews popping up on Twitter (I’m reasonably new to Twitter). I usually don’t know what to make of intensely wordy and existential reviews, people who say that reading Crystal Eaters is like setting your brain adrift in the primordial muck of your ancestral wandering and watching it develop a higher consciousness as you stand stuck on the shore of your own punitive physicality. What?

I read it recently. I had high expectations. I’d never had a reading experience that was like tripping balls. I still haven’t. I don’t know that I want to trip balls when reading something. So, Crystal Eaters. It had one of the coolest concepts I had ever heard of, so naturally, while awaiting its release, I started to imagine what the book might be like. Months of imagining. It was like being in high school and idealizing the girl who has the locker across from you and finally having the chance to speak to her when you both find yourselves the last ones out the door from spanish club. And boom! You walk up with the perfect opening line only to hear her squeak one out because she doesn’t notice you coming and she’s never noticed you. All of this is to say that reading Crystal Eaters was nothing like a fart. It was a book that kept me up late. It frustrated me. I talked to my fiancé about it endlessly and now she is reading it because she wants to have a better idea of what I am talking about so we can discuss it further.

July 24th, 2014 / 1:07 pm

Eating Yourself to L()ve: A Review of Autophagiography

|

Autophagiography

by A & N

gnOme, 2014

192 pages / $12.00 buy from Amazon

Rating: 8.5

|

Autophagiography, the latest release from the small pseudonymous press Gnome Books, is a documentary epistolary ‘novel’ composed of temporally-congruent email and twitter messages between two persons, followed by a short treatise which defines and theorizes some guiding principles for the weird ‘saintly’ love/friendship at the center of the story. In form and content, the book is one-of-a-kind and hard to describe. Here are some salient features:

Language/Style: the protagonists communicate in a kind of poetically inspired intellectual style that is both sublime and ridiculous. For example, “Dear One by Whom We Orient Ourselves to Ever Greater Bewilderment” (8), or, “Your words make me blush in my tomb! Idiorrythmia freaks, torment chewers, self-eating love-worms…” (92). It is difficult to imagine people actually writing to each other like this and at the same time obvious that none of it is made up. At its best, the text effortlessly spins out stormy passages of living prose-verse worthy of Lispector and Bataille (both of whom are referenced as sources of inspiration). At its worst, it repetitively babbles with baroque terms of endearment perhaps better to have been left on the cutting room floor—though to have done so would have been impossible. Overall the idiosyncratic and spontaneous authenticity of the whole thing only accentuates its mysterious hyper-fictionality, haunting the work with the sense that the writers may indeed be flirting with madness, or better, hallucinating themselves out of existence: “Love is not for this life and yet it is precisely here that it is happening” (70).

Ideas/Themes: As the clever one-word title indicates, the book records and enacts a process of autobiographical self-eating that attains and/or strives for a kind of sanctity. The (non)relationship is platonically romantic: “This is not a ‘relationship’. This is love itself (in world and not of it). But how we relate!” (72); “This is not to say that what happened is not miraculous! … Why? How? All the more that we were never alone!” (102). It also involves a number of interesting mystical dreams or visions: “Something unlike I have ever experienced really happened within me and to the whole world at the same time. No way to explain, but it was like swallowing the infinite auto-recursive spiral all the way, like eating one’s head and exiting stunningly unharmed into an other side which is more this one than this” (178). Whether or not the authors actually become saints is a silly question that the text nevertheless makes one ponder the meaning of. The reader may just as easily feel sorry for them or wonder why they do not just run off together. In the end this reviewer was left happily swimming in a peaceful existential desperation reminiscent of E. M. Cioran’s Tears and Saints (a text mentioned several times), where the divine truth of sanctity is as real as the unreality of the universe: “Can it be that God is only a delusion of the heart as the world is one of the mind?”

Identity/Authorship: This is a significant accidental experiment in documentary authorship, an ‘as-is’ book with several delightful surprises and contradictions. The formal interplay between-across email and twitter embodies the multi-channeled and erotically vexed nature of socially networked existence only to feed it back into the mouth of the book as the obvious and maybe only possible earthly offspring of spiritual friendship. Indeed the conception and editing of Autophagiography becomes an important part of the narrative itself, so that the text literally and narratively eats itself into its own real present, like some kind of monstrous love-child proverbially devouring the authors out of their inexistent sub-oceanic house and home: “The monster is here and I cannot stop it, I don’t want it ever to shut up. Whatever happens in this life there will be the fault of this cataclysmic now screaming to me, deafening me with the echo of a deformity that I always was” (73). At the same time, the book is imbued with its own palpably literal and melodramatic worldly reality. The communication-communion endures and reflects upon the difficulties it causes for the saints’ other true loves and also shamelessly relishes its own embarrassing confessional responsibility: “Not one syllable of our words would I alter, not one atom of our sigh, but from today forward, this new day of a new life, I must somehow address you more sanely, in words that proliferate and expand to befit more and more the purity of this intolerably sweet friendship, this little bond through which we are indeed becoming ‘as close to nothing as possible’” (129). The open secrecy of the work is accentuated by the discoverability of the authors’ worldly identities and their entrapment within a web of recent events and current interests (Lovecraft, Argento, Cioran, Thacker, Land, Lispector, Meillassoux, Negarestani).

In the live medium of its essential imperfections, Autophagiography is virtually-actually worse and better than this world, a worst best and best worst that would prove to open a way to paradise, if only if it were possible to read it properly. One can only hope without hope that its authors somehow find happiness in this sphere or the next, or at least in a weird new somewhere that is neither.

July 22nd, 2014 / 12:00 pm

Beijing Doll

|

Beijing Doll

by Chun Sue

Riverhead Books, 2004

240 pages / $17.00 buy from Amazon

|

In the world of Chinese lit translated, a common branding method is to plaster somewhere on the cover: China’s Banned Bestseller or The Controversial Banned Sexual Exploration, A New Generation, and so on. Goodreads has at least two lists of China’s Best Banned Books – and it’s become a sort of nerd-o-meter to detect new-to-the-genre readers by seeing if they’re lured to the Banned Bestseller stuff or to more ‘serious’ Classics or Mo Yan (technically banned, but, acceptable).

July 8th, 2014 / 5:01 pm

The Fun We’ve Had

|

The Fun We’ve Had

by Michael J. Seidlinger

Lazy Fascist Press, 2014

168 pages / $11.95 buy from Amazon

Rating: 7.9

|

How do you write a thrilling and entrancing Alt Lit novel?

Start with a chorus of disembodied voices telling us that “the waves are helloes; the incoming storm the sincerest goodbye. Like every single one of us, they are holding on. We held on until we could no longer hide. No one can hide out at sea.”

June 24th, 2014 / 12:00 pm

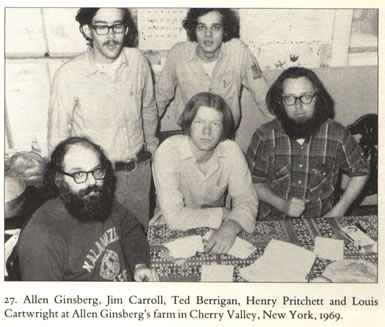

Forced Entries: The Downtown Diaries 1971-1973

|

Forced Entries: The Downtown Diaries 1971-1973

by Jim Carroll

Penguin Books, 1987

196 pages / $15.00 buy from Amazon

Rating: 8.0

|

Although The Basketball Diaries was blanched by LEO, High School English, and pop revisionism, Forced Entries, Jim Carroll’s 1987 follow up still has a lot of charm.

Subtitled The Downtown Diaries 1971-1973, this book tackles the emergence of the lost and romanticized Downtown scene. As a poet, Carroll was active in readings at St. Mark’s Cathedral and a Warhol Factory regular. It’s a short book, under two hundred pages, and it’s framing as diary entries allows Carroll a soft touch as he relates observations and anecdotes.

June 17th, 2014 / 12:00 pm

Cosplayers

Cosplayers

Cosplayers

by Dash Shaw

Fantagraphics, 2014

32 pages / $5 buy from Fantagraphics Books

Rating: 7.8

Dash Shaw’s other comics, especially 2010’s BodyWorld, push the boundaries of the comics medium in exciting ways, but they can also be daunting, especially to readers who are not comfortable knowing which panel to read when in a comic book—let alone be ready to turn the pages on their axis. However, Cosplayers is a much more accessible starting point in Shaw’s oeuvre. The one-shot does not play with form as much as Shaw’s other work, but it still showcases his lush color palette and his adventurous concepts.

June 3rd, 2014 / 12:00 pm

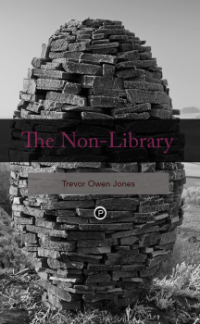

On Exactitude in Non-Library Science

The Non-Library

The Non-Library

by Trevor Owen Jones

Punctum Books, 2014

104 pages / open-access (e-book), $11.00 (print) buy from Punctum Books

Rating: 9.0

Dear T.,

Already a few years ago now you composed a correspondence to mark the appearance of Judith Schalansky’s Atlas of Remote Islands: Fifty Islands I Have Never Set Foot on and Never Will. I return to that correspondence, on the publication of your first book, The Non-Library, because to do so seems to me somehow apposite. That may be the reason I find myself writing to you, to try to understand my sense of just why. READ MORE >

May 15th, 2014 / 1:15 pm