Russian Novels

Russian Novels

by Luke Bloomfield

Factory Hollow Press, 2014

Unlike the archetypal Russian Novel, Luke Bloomfield’s Russian Novels is little more than a centimeter or so thick, 60-some pages of poems with names like “The Duffel Bag” and “Fisticuffs.” Most of the poetry inside the book feels as flat as the book, a sort of day-old-seltzer meets #normcore poetics. The first poem, for example, begins “When I go 2 Paris / it is like Paris,” and goes on to blanket classically French France in stereotypical American stereotype: “Voila, Paris France! / All the cigarettes everywhere / are pronounced cigarette.” In this trick, Bloomfield spells cigarette cigarette and, abracadabra, we the audience mind-mold the word like Play-Doh. The point seems to be that language is as wild and plastic as a “bird” that appears, disappears, and reappears throughout Russian Novels, always cast as simply “bird”—and yet each of these birds, conjured in Bloomfield’s magic, manages to manifest a somewhat unique form. The limitation of such simple syntax is clear however, when, in certain poems like “The Affair I Had With Sweden,” the author tries to reveal some semi-complicated personal gunk: “It sent me over the edge. / I don’t leave the kitchen ever. / All day I hack food into Swedish shapes. / And you know what else I do.” I don’t know, do you? What are we supposed to know? I know Russian Novels is not a novel; the MARC code on the back of the book says Poetry and the Very Poetic Word “flotsam” appears in the title of a poem on page 47. I know that the cover of Russian Novels presents a blurry photograph of a nose, but I don’t know whether or not this is Bloomfield’s schnoz? And I just don’t know what Bloomfield thinks he knows that I know.

Flat affect tends to belie emotional content, and in lines like “Pity me. I have nowhere to walk,” Bloomfield has incanted a dissociative poetics reminiscent of Nintendo sidescroller. The action is pretty fun but Russian Novels, like video games, lacks a third dimension. The book’s tender moment of intimacy (MOI), imo, comes in the author’s dedication, “for my sister.” A close second: Bloomfield’s confession that he sleeps in astronaut-themed bed-sheets.

***

Manual for Extinction

Manual for Extinction

by Caroline Manring

The National Poetry Review Press, 2014

The earth in Manual for Extinction is a dour place where to be “alive was as good as dead.” The manual doubles as a field guide for understanding this wilderness-less mess, a contemporary big-boxed landscape that, lucky for us, Caroline Manring has surveyed with her poetic binoculars. Fans of “flotsam” will be pleased to find the word has survived End Times (hi flotsam!) and can be found in this book alongside lots of titles that start with the word how, as in “How to Go Extinct” and “How to Write a Debut Novel.” There are a few outliers, such as “The Cartographer’s Children Go Without Shoes,” an evolutionary meditation that invokes the proto-winged avian-ancestor, Archaeopteryx, in which “A fossil is deciding / whether to save us.” Manring demonstrates a cool familiarity with Biology while at the same time grappling with the paradox that Borges called exactitude in science. “A copy of a wolf & the wolf itself / are the same if you draw them both.”

A world of illustrated (aka dead) dodo birds, lost turkeys, and dilapidated human remains sounds shitty and scary but it is also quite literally what we’ve got. In place of live starlings and spring robins we might increasingly encounter the complexity of nature only in the complexity of research finding that predict diminishing populations of red-winged blackbirds, ruby-throated hummingbirds, and buffleheads alike. Manring writes in sympathy with these vanishing species, “I want less & less to be in present use.” Would that we were all to follow such a guide.

***

My Enemies

My Enemies

by Jane Gregory

The Song Cave, 2013

We’ve a lot to learn from My Enemies. As the title suggests, many things are often as much what they are as what they are not. Take, for example, Jane Gregory’s sonic yin and yang, “Cymbals / when washed up or out to sea are silent.” Much like the potential for both mute and crash held in tempered bell bronze, Gregory has set temporality in opposition to intuition, and by that I mean . . . listen to her ring like an animated slomotion gif of a Zildjian: “I recognize the tongue of the wolf / before it is in the wolf’s mouth.”

Wallace Stevens sez “Poems must resist the intelligence / almost successfully,” and My Enemies outmaneuvers the brain’s insistent cognition, which just cannot compute Jane Gregory. The many poems entitled “Book I Will Not Write” are, as announced, books never really written. But in the poetic summation of these non-books, the author has penned a must read.

Though unable to locate a single instance of “flotsam” inside this text, I found plenty of poetic words like “guncotton,” “ecdysis,” and “Proust.”

***

Peter Nowogrodzki lives in Hudson, NY

Inside Madeleine

Inside Madeleine You Can Make Anything Sad

You Can Make Anything Sad Can’t and Won’t

Can’t and Won’t The Whole of Life

The Whole of Life Crystal Eaters

Crystal Eaters The Selected Letters of Robert Creeley

The Selected Letters of Robert Creeley Russian Novels

Russian Novels Manual for Extinction

Manual for Extinction My Enemies

My Enemies

Made To Break

Made To Break Bald New World

Bald New World

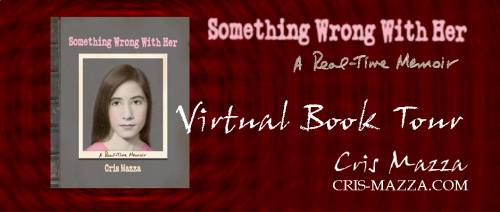

I was prepared to sit here and rant about having to change my author photo to a more friendly, smiling image, certain that practically zero men ever get told they need a smiling photo (or to “look cute” as another writer wrote about being advised). This advice (and that I felt pressured to follow it) was particularly troubling this time, for this book: because the book is nonfiction, because part of it is about female sexual dysfunction, about not feeling sexy in a sex-hungry, sexiness-demanding world. The photo I had chosen, a selfie, showed the mood I thought the narrative conveyed.

I was prepared to sit here and rant about having to change my author photo to a more friendly, smiling image, certain that practically zero men ever get told they need a smiling photo (or to “look cute” as another writer wrote about being advised). This advice (and that I felt pressured to follow it) was particularly troubling this time, for this book: because the book is nonfiction, because part of it is about female sexual dysfunction, about not feeling sexy in a sex-hungry, sexiness-demanding world. The photo I had chosen, a selfie, showed the mood I thought the narrative conveyed. When the smiling photo was requested (not by my publisher), I didn’t have the time (and was very low on inclination) to create another photo, to “try” to smile for it without appearing conscious it had been requested. So I went back to the most recent photo I had where I was smiling (also containing my dog, the same dog, so not that long ago). Unfortunately, it was taken in the summer and I was wearing a tank top. I truly and firmly did not want to be showing skin in the author photo for this book.

When the smiling photo was requested (not by my publisher), I didn’t have the time (and was very low on inclination) to create another photo, to “try” to smile for it without appearing conscious it had been requested. So I went back to the most recent photo I had where I was smiling (also containing my dog, the same dog, so not that long ago). Unfortunately, it was taken in the summer and I was wearing a tank top. I truly and firmly did not want to be showing skin in the author photo for this book.