Behind the Scenes

Approaching an Ideology of Art

In order to sit down and establish any sort of ideology1 that guides my life, I really have only a single point to consider: art2 is, without a doubt, what is most important to me. Out of everything. I say this without a hint of irony, with a complete presence of sincerity: everything that has ever been important to me has been mediated by art, to some degree.

Perhaps this is easy for me to say because I equate art with pleasure. Or the idea that art is beauty (as a definition from dictionary.com would like to suggest). If this were true then I wouldn’t have anything to say here. But, the unfortunate thing is that there is a lot of bad art that makes me furrow my brow and launch into hyperbolic rhetoric or a complete insincerity (read: irony). The other negation to the aforementioned declarations heeds itself to my own ideas in an appreciation of affect over visual aesthetic: i.e., something ugly, terrifying, and evil can bring pleasure.

I am not an overly-depressed person. I am (fairly) high functioning in a pretty normal way. I have no desire to be constantly escaping from reality. Kneeling at the temple of Art is not about escapism for me, and I think that’s why I inherently hate the idea of mediating an experience of art (exclusively) through empathy (this is why I will always champion modes of art that lie outside of representation3).

I occasionally feel like when I make this declaration, I am widening a divide between myself & the general public. I say this without elitism. The problem is making a statement like this seems to establish binary opposition: if I don’t like representation, I must like crazy non-narrative abstract shit. Right? I mean, that binary presupposes the person who is contrasting her or his own approach to art with mine is able to conceive of an approach to art that is outside of representation (and this is part of why my mother has no idea in regards to what I am interested in and what I am doing when it comes to “art”).

But here’s the thing: I love narrative. I have no desire to escape narrative. Of course, throughout my experiences with art I have grown mostly tired of archetypal narrative arcs, neatly wrapped up stories, etc etc. But that’s not the point. What I look for in art, what I aim for in art, ultimately, as I’ve said many noted many times in comment threads, is affect.

My obsession with, and definition of, “affect” has been developing over the last few years. The key ingredients that have been simmering in the crock-pot of theory within my headspace include: an engagement with the theories espoused by Tel Quel (though mostly ignoring the psychoanalytical aspect), Antonin Artaud (especially his ideas on theater & cinema, but also incorporating his entire praxis), obsession with the films of Philippe Grandrieux & Martine Beugnet’s reading of Grandrieux’s films & recent French cinema, and intense consideration of what it means to be against representation (isn’t that basically a Sontag article? I should probably reread that…).4

So, to simplify what it is I mean when I appreciate and strive for art that cares about affect more than anything else is the following: an idea that a work of art becomes an experience that can directly influence the emotional or even physical state of the reader (reader here to approach the post-structuralist idea of the “text,” standing in for book/movie/visual art/whatever) directly. When I say I am against an empathetic reading, it is not because I want to be cold and unemotional, it is because I want the feelings I experience when I encounter a work of art to be MY feelings, not the caustic feelings of the protagonist of a novel, etc.

To provide an example of this, I think it’s probably best to start off with an example from the art world. Gregor Schneider is one of my favorite artists. It would be possible, I guess, to explain what he does as basically making high concept ‘haunted houses.’ Not literally, of course, but the experience is similar: Schneider creates spaces and the viewer of the artwork (who is, in this case, actually a participant) explores the spaces. Schneider often populates his spaces using ideas that relate to the uncanny: the double, a man who may or may not be dead, architectural constructions that make little sense, etc.

In 2007, Schneider staged an exhibition titled “Weiss Folter,” or, “White Torture” in English. The following description is taken from Schneider’s website:

The Kunstsammlung is presenting a new ensemble specially created by Gregor Schneider for this exhibition. A series of rooms – accessible to the exhibition- goer – has been built into the existing architecture of the museum: long corridors and confined cells equally reminiscent of intensive care wards and isolation units, of protection and confinement, that can be read either as zones of extra attentive care or of social and sensory deprivation. Individual rooms call to mind prison cells, interrogation rooms, holding areas or exercise tracts under constant surveillance. The artistic strategy of doubling and replication, that is fundamental to Gregor Schneider’s work, is again in evidence here. The exhibition is a response to images circulating on the Internet of the United States’ maximum security facility Camp V at Guantánamo Bay on Cuba, a no-man’s-land that is shielded as far as possible from the public gaze. The title of the exhibition also references the secret and the clandestine. ‘White torture’, also known as ‘clean torture’, is used of methods that are designed to destroy a person’s mind without leaving any external evidence and hence are extremely hard to prove.

While, I suppose, you could argue that the interiors are representative of pre-existing interiors (those of maximum security facilities, etc), it’s plain to see that these spaces, these interiors are literally there. You are not looking at a photograph of said space and trying to “enter the mind” of a prisoner in order to experience what that kind of room can do. Instead, you are, in your own, physical body, encountering the space. There is no level of distance that can deaden any reaction you might have. You are neither having the same experience that a prisoner of such a space would experience: you are having your own experience. Your own experience with the work is something that no one else will have, because, literally, they are not you. My interest in this work of art is that it is not passive, it is active. It is, literally, an experience, an event.

Next, let’s consider an example of this degree of “affect” that can be found in film. I will use the aforementioned Philippe Grandrieux. Grandrieux is a brilliant French filmmaker who trafficks in terror and affect. He is, in my opinion, the primary example that can be found in Martine Beugnet’s quintessential text, Cinema and Sensation.

Beugnet takes Artaud’s notes on his “cinema of the third path” as a launching point in developing the ideas set forth of “cinema and sensation.”

At present, two courses seem to be open to the cinema, of which neither is the right one. The pure and absolute cinema on the one hand, and, on the other, this sort of venial hybrid art. The latter persists in expressing, in more or less successful images, psychological situations which are perfectly suitable for the stage or the pages of a book, but not for the screen, and which only really exist as the reflection of a world

which seeks its matter and its meaning elsewhere. . . . Between purely linear abstraction (and a play of shadows and lights is like a play of lines) and the film with psychological undertones which might tell a dramatic story, there is room for an attempt at true cinema, of which neither the matter nor the meaning is indicated by any film so far produced.5

And to quote Artaud further from Beugnet’s book (Because I have a PDF of that handy & not the primary Artaud text):

The power of the cinema thus rested with ‘purely visual sensations’ (Artaud’s writings correspond, of

course, to the end of the era of the silent movie), ‘the dramatic force of which springs from a shock on the eyes, drawn, one might say, from the very substance of the eye, and not from psychological circumlocutions of a discursive nature which are nothing but visual interpretations of a text’ (Artaud [1928] 1972: 20). On the one hand, Artaud’s claim with regard to the vocation of the medium of the moving image stresses the need for a cinema that would draw its raw material from the recording of a pro-filmic reality rather than resort to the purely conceptual constructs of the proponents of the abstract film avant-garde. Crucially, if he rejects it as a formal a priori, Artaud does not rule out abstraction as part of the actual imaging process; the following description of the movement and mutations in/of the images suggests that the frontier between the figurative and the abstract remains fluid. Artaud thus calls for an initially figurative cinema, but one where film forms should nevertheless be allowed to develop independently from ‘realistic’ narrative adaptations and ‘play with matter itself, [to create] situations that emerge from the simple collision of objects, forms, repulsions and attractions’ (Artaud [1928] 1972: 21).

What I want to highlight from that text block (the entire context of which I think helps to illustrate what this means) is the following push for film [in my conception here, all art] to “play with matter itself, [to create] situations that emerge from the simple collision of objects, forms, repulsions and attractions.” This suggests, to me, an idea to let things develop their own experiential logic, and not rely on some insistence towards being representative & fitting a pre-established conception of logic.

With that said, I’d like to approach the films of Grandrieux, in a somewhat abstract manner (part of my reticence towards saying otherwise is related to the idea that these things I am talking about all exist as experiences in their own right, so my textual approximation clearly cannot express what these things do). Here’s Grandrieux in a fantastic interview with Nicole Brenez:

NB: La Vie nouvelle is a film devoted to the inaccessible, but at the same time it offers us everything. It is a film about abandonment, but it never becomes melancholic, which would be the usual way of depicting loss.

PG: There’s no melancholy. The film was made under the sign of enormous heath, vital energy, the blazing sun. That surpasses desire, it is even more archaic and formative; it comes from the sun itself, from a star beyond us that we aspire to, in a totally chaotic way. This aspiration towards great energy and happiness, it infused the film, which we made in a wild state of joy, six weeks of shooting like a single stroke, without a second thought [arrière-pensée].6

SO, it’s pretty easy to understand how walking through architecture is an experience, an event in its own right, but how can watching a movie be an event? Grandrieux, and a select group of other filmmakers, seem to address Artaud’s idea of “the dramatic force [springing] from a shock on the eyes, drawn, one might say, from the very substance of the eye, and not from psychological circumlocutions of a discursive nature which are nothing but visual interpretations of a text.”

The cinema of Grandrieux is narrative, as in, there are related events that happen, and there is a story to be found, but the story, the characters, are not where pleasure in watching the film is derived from. As a textual example, let’s jump back to Grandrieux’s first narrative film: Sombre. Early on in the film, Grandrieux interjects a scene of a young boy, blindfolded, blindly reaching out his arms, seeming to search for something, in front of a large cube, near the ocean. A traditional cinematic reading of these scene, which is completely divorced from the narrative, characters, and even setting of anything else in the film, would, probably, insist upon the scene as metaphor or allegory. This is, of course, completely unnecessary. Grandrieux has insisted that the scene is thrown at the audience with the sole motivation of helping to create the atmosphere of tension and uneasiness, the uncanny, not within the diegesis of the film, but rather for the viewer of the film: in this way the viewer becomes, once again, a participant. The unease the participant experiences is not tied to empathy– one in not empathetically feeling disrupted because a character within the narrative, the diegesis of the film, is struck with confusion, or disrupted himself, rather, outside of the narrative, outside of the diegesis, Grandrieux is hoping that you can enter an emotional & mental space where this atmosphere exists. It’s a disruption to the traditional mode of viewing.

I started thinking about all of this– the idea of art and its affect, when I watched David Lynch’s Inland Empire for the second time in 2007. For more ideas relating to the establishment of ideas toward an “experiential movie,” (and so I don’t take up too much real-estate within this blog post), click through to my review/essay on the Lynch film.

OK, so, this far we’ve skimmed the surface regarding visual art & movies, but since this is, primarily, a blog dedicated to literature, I guess it’s time to move on to the written word where, it seems to me, it is admittedly most difficult to combine narrative with a direct experience.7 The Tel Quel group approaches this in a very, somewhat obtuse way. At least, Philippe Sollers himself does. Sollers attempts (this is not exclusively what he has done, but part of his praxis) to write from a sort of perspective that floats from Sollers as the writer as a character in the story, to the perspective of the reader his or her self, outside, once again, of the diegesis. This is not accomplished with the second person pronoun of “you,” — rather, it attempts a viewpoint that belongs to the reader alone. With this positioning, at first, there’s a sense of disorientation– generally, when one reads, they are expecting to find a perspective of representation, when there is no implicated perspective, and the positing is placed on the reader (once again, the participant), this is confusing as fuck. But, if you stick with it, shit becomes kind of amazing.

I will, perhaps regrettably, diverge from Sollers because I don’t know if I’m quite in the position to talk about him how I want to (though, if you’re interested, Barthes wrote an excellent series of essays on his work that while it does not specifically approach Sollers writing as specifically experiential, it’s a great read nonetheless). I will move on, now to Maurice Roche, another fantastic French author tied to the Tel Quel group. There’s only a single full novel available in translation (Compact from Dalkey Archives), but if you dig deep enough you can find a lot of fantastic shit in translation in neglected anthologies and literary journals.

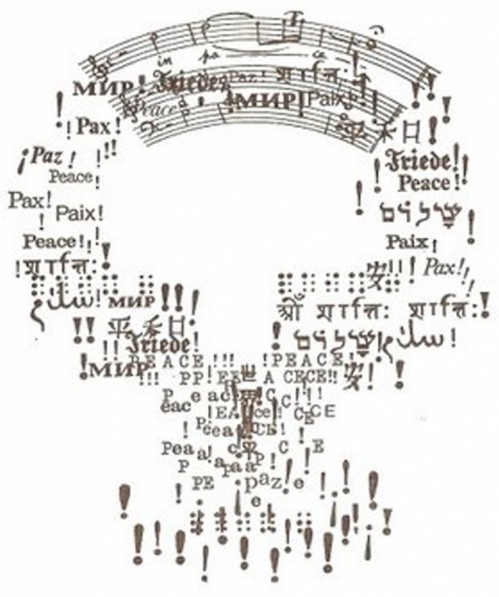

Roche writes in a highly visual style, somewhere between concrete poetry, the post-structuralist functionalism of House of Leaves, and conceptual writing by artists8. Roche always said that he wrote his texts as if he were writing a musical score (albeit in a way far distant from Michel Butor’s literal appropriation of that technique in Niagara) with many different ‘polyphonic’ voices. While the narrative itself stays distance, the experience here is decoding the signifier into a cohesive whole. It’s not a simple gimmick of cracking a code or anything, rather, the heterogeneity present in the text allows a polyvalent reading which, in turn, emphasizes the idea of reading as an experience (vs. the experience of empathy).

The Tel Quel group, in their discussion of progressive literary methodologies, spends a lot of time discussing the level of the signifier. By level the group means how the signifier is functioning. The level of a signifier in regular text, particularly in the writing of narrative text, is generally once removed, because ultimately words are representative of ideas and/or material objects.9 Tel Quel spent some headspace trying to figure out how to eliminate the distance, while still staying within the realms of words (heading towards the degree zero of writing). Tel Quel gets really confusing at times (and I don’t care for it, as I’ve mentioned, when they bring in psycho-analysis), but to me engaging with this idea is something that should not have ceased.

If you’ve come this far, you’re probably wondering what any of this has to do with my formerly established ideas that I’ve nurtured via Dan Hoy’s writings on The Pin-Up Artist, especially in contrast to what I said at the beginning of this blog post– that “I have no desire to be constantly escaping from reality.”

This is a fact. My bombastic desire for, as Kathy Acker put it, “all the food and medicine you need […] Luxury, fun, etc. everywhere all the time,” is not incongruous with my refusal to use art as mere escapism.

OK, to articulate this, let’s consider what I have already said about experiencing something via empathy versus experiencing something first hand: clearly, I have established my insistence upon the latter. This is what I mean when I say that I am tired of THIS world. I don’t want to escape into a DIFFERENT world, because that is not something that is physically possible. I want THIS world to CHANGE. As someone with a preference for experiences over escapism, I think this is the only thing that makes sense. Despite insisting upon the shortcomings of realism, I am looking for new experiencing in real life. All of this, ultimately, amounts to a desire for constant-fucking-pleasure. The pleasure of the new.

It is now the point of the blog post in which I will end by quoting Baudelaire:

Our brains are burning up! — there’s nothing left to do

But plunge into the void! — hell? heaven? — what’s the odds?

We’re bound for the Unknown, in search of something new!10

1:i·de·ol·o·gy /ˌaɪdiˈɒlədʒi, ˌɪdi-/ [ahy-dee-ol-uh-jee, id-ee-] –noun, plural -gies.

the body of doctrine, myth, belief, etc., that guides an individual, social movement, institution, class, or large group.

2:art [ahrt] –noun

an all-inclusive word used by M Kitchell to indicate any or all of the following: a text, a movie, music, dance, sculpture, performance, visual art, painting, sound, drawing, etc, etc. (The point is when I say “art” I am not limiting the word to mean “visual art” or “fine art,”– it is also how I refer to books and movies and so on)

3: My favorite author who is arguably representational is Ballard, but to me Ballard is far more exciting conceptually, for the ideas that he brings, and architecturally, for a demonstration on the affect of space, than he is in terms of characters or plot.

4: I get the impression that a Deleuzean approach to art would fit in here too, but I’m ridiculously under-read when it comes to Deleuze, so I’ll leave him out for the time being.

5: I should note that I, of course, am not satisfied with “psychological situations [as] perfectly suitable for the stage or the pages of a book,” but that’s not the point here

6: Pretty neat huh? Grandrieux is clearly showing his ties to Bataille here, which makes him a man after my own heart.

7: You might ask: “If it is hardest to accomplish what you’re after in writing, M Kitchell, then why the fuck do you spend more time writing than working in any other medium?” Well, the answer to that is that: writing is a lot fucking cheaper than making a movie well or constructing a fucking building to walk through. It sucks but hey that’s life.

8: This idea of conceptual writing is separate from the project engaged by such contemporaries as Kenny Goldsmith, Vanessa Place, and Robert Fitterman.

9: Current trends in philosophy (object-oriented ontology & speculative realism, specifically) add and engage with this idea in a really amazing way, but I’m not as yet engrossed in & familiar with the ideas they present to feel comfortable in introducing them here. However, if you’re interested, Meillassoux’s After Finitude is a great place to start.

10: “Le Voyage,” translated by Edna St. Vincent Millay, Flowers of Evil (NY: Harper and Brothers, 1936)

Tags: affect, artaud, baudelaire, gregor schneider, kathy acker, philippe grandrieux, tel quel, the future is now, the pin-up stakes

Blog w/ footnotes; you crazy.

if you think you can create an ideology for yourself, then you don’t know what ideology is.

great comment man!

i was trying to be helpful. consider what i am saying.

what you’re saying is “you’re doing it wrong.”

how is that helpful?

that’s an interesting translation, but it is not what i meant. what i meant, if i have to translate myself, is that you cannot “establish” an ideology which guides your life, because that is not how ideology works. ideology, in fact, establishes you.

i don’t mean to make you look bad or whatever. i just want to encourage you (and whoever else may be interested in more than a dictionary level def. of the word ideology) to read more about the subject, esp. considering its overwhelming effects.

while I understand where you’re coming from here, as it, perhaps, seems “unfair” to completely abuse highly prevalent terminology (i.e. “if words can mean whatever you want them to mean then they don’t mean anything”), but I also believe, intensely, that words are one of the things that we can assign a truly plural heterogeneity to in our search for the construction of meaning. my insistence upon choosing the word “ideology” (which I only approach at the beginning of this post, choosing mostly to abandon it as I move through what is at the heart of what i’m writing about here) is based on my appropriation of the dictionary definition that I cite– i’m well aware that it suffers an historicity that colors its meaning, but i refuse to accept that the idea behind a word can be fixed in such a stoic nature.

this is off topic and i apologize, but i figured it’s a good place to ask: would you mind throwing out a few art critics you hold in high esteem? also, i’m looking for a good art history book or two, mainly of the twentieth century. i’m not looking for highly theoretical writing (or maybe a little), but stuff leaning a bit more toward the historical and aesthetic. for instance, there’s an excellent book (mainly about post-modern lit) called Literature and the City, which traces po-mo’s development contiguously with development of urban areas. not just like this, right, but sort of like this, but for art. or something like Kenner’s A Homemade World.

i liked this post and there are a ton of people in it i know nothing about except their names.

“I also believe, intensely, that words are one of the things that we can assign a truly plural heterogeneity to in our search for the construction of meaning.”

this sentence is pure ideology. you are taking a thought which is not your own and defining yourself by it. i don’t say we all don’t do it. i am just pointing out the fact that this is important. why/how did this thought take your mind and not another?

also, citing a dictionary is its own kind of ideological call (which you don’t actually do, i.e. where did you get your information? that’s the point of citing…). it calls for the agreement of people who don’t know about (or care to think more about) ideology than whatever def dictionary you fed them. take this easy bit and agree with me…

and i know you only use the word at the beginning, but a more complex understanding of ideology would change a lot of what follows, i think.

I’m a big fan of the regular contributors (historically) to he magazine October, though that more often intersects with theory, albeit in a much more approachable way than really heavy shit (and in my experience there’s not a ton of psychoanalysis involved which is AWESOME)– Rosalind Krauss & Yves Alain-Bois being my favorite.

I’m not sure what the best place to look for a historical approach would be, as I tend to look for and read books that are more based thematically or within “movements.” Also, art for me basically starts in the 20th century, but that’s a short-coming I’m willing to admit.

I haven’t read them in their entirely, but the Art Since 1900 books seem to be pretty good; when I was an undergrad we used the second volume in a contemporary art history class (and Krauss & Alain-Bois are present). The “Documents of Contemporary Art” series are collections of essays grouped by “themes,” like “The Sublime,” “The Grotesque,” “The Cinematic,” etc. No pictures, but lots of good ideas (plus, you can always just google image search something if you need a visual point of reference).

Rudi Fuchs is an Austrian dude who has been writing about art, and he approaches it, sometimes, almost conversationally, and tends to write about pretty great shit, though I’ve basically only encountered him in monographs of specific artists (which is where I glean most of my info– reading books on specific artists that turn me on).

For a sort of “primer” of the 20th century avant-garde I always recommend Richard Kostelanetz’s Dictionary of the Avant-Gardes.

very, very helpful. i appreciate it. will definitely check out Krauss and Alain-Bois.

here is a box

[ ]

here is where this article is

a [ ]

do you want me to apologize? i’m not disagreeing with the ideas you’re suggesting about what “ideology” “means,” but if i had decided to approach the idea of an ideology it would indeed be an entirely different post. if i had insisted on this meaning of it, and refused to ignore it, then i would not have used the word “ideology.” but hey, i did. any sort of ideology is not actually the point of the post, which i don’t think is confusing in any regard. if anything it’s more of steps toward a manifesto that provides textual examples. so why is this a giant issue? like i’m honestly curious. you can easily read my responses as defensive, sure, but i just wrote a 3500 word blog post that focuses mostly on affect & experiential art, and suddenly i’m being called to arms about the semantics of the word “ideology.”

ok. i’m going to bed. it’s late where i am. i don’t want you to apologize. i’m glad you posted your post. there were things i never heard of that now i have heard of. things i am interested in taking another look at. i just want you to think about ideology and how important it is. i feel like a goddamn after school special now, or topanga.

you say;

“any sort of ideology is not actually the point of the post, which i don’t think is confusing in any regard.”

and your post is called: “Approaching an Ideology of Art.”

but i don’t want to nitpick.

“I want THIS world to CHANGE”

me too. that’s why i care enough to write this ‘semantic’ challenge to your use of the word ideology. not because you do it, but because many people do.

and i know it’s complicated and most people don’t want to spend their weekends reading the wife strangler althusser’s ponderings about “Ideology and Ideological State Apparatuses,” but if anyone cares i think it’s as good a place as any to start: http://tinyurl.com/2b4hxq (or find it on a better looking website/book/collection but that’s free and right there so why not take a look?).

While I am sympathetic to Henry’s objections to the ideological space you’ve crafted here, I would like to remind him of something very important that Louis Althusser once said: “It is necessary to be outside ideology, i.e. in scientific knowledge, to be able to say: I am in ideology […]”. With this very provocative essay, we may find Mike at this juncture–or we may not. Suffice it to say Mike “ideology of art” bears no reference to the Marxist critique thereof, which in fact might be your point–that exactly what “ideology” wants is for you to seize “another” meaning from it then the form it actually takes. And that’s a point you could legitimately address to every single post made on this site, so maybe it would be canny to let it drop. Your call.

I like this post a lot (!), Mike; it’s a topic very close to me, but I’m not sure that I agree with you at all. And it’s an improvement on that Dan Hoy essay, which actually, I have to echo Henry in saying, is pure ideology.

Really, really, really liked this post, Mike.

Gonna get hold of that Beugnet book — thanks for mentioning it, I had not heard of it before. (Are you familiar with Steven Shaviro’s book The Cinematic Body? I think you’d dig it. His analysis of Andy Warhol’s films is worth the price alone, but that puppy is a treasure trove; and if I am remembering correctly, he engages with Massumi’s “affect” theory.)

Have you read Kant’s Critique of Judgment? I’m wondering how/if his idea of the beautiful being that which excites the freeplay of the imagination might intersect with your desire for an Artaudian non-representational affective aesthetic “ideology”? My reading of Kant and my reading of your post here suggests a possibly fruitful correlation.

re: that screencap from Don’t Deliver Us From Evil reminds me of that line in the Surrealist Manifesto where Breton writes: “Surrealism will usher you into death, which is a secret society. It will glove your hand, burying therein the profound M with which the word Memory begins.”

Also, lastly, how can I get hold of other Philippe Grandrieux films with English subtitles besides Sombre?

To clarify, when I said “Mike ‘ideology of art'” I meant “Mike’s,” and when I followed that with “your point” I was referring to Henry…

Also, the quote I’ve taken from Althusser actually appears in the ISA essay that Henry links to. It’s a very rewarding read and one of the crucial works of philosophy of the 20th century.

Another take on ideology (if you don’t want Althusser):

212

Ideology is the intellectual basis of class societies within the conflictual course of history. Ideological expressions have never been pure fictions; they represent a distorted consciousness of realities, and as such they have been real factors that have in turn produced real distorting effects. This interconnection is intensified with the advent of the spectacle — the materialization of ideology brought about by the concrete success of an autonomized system of economic production — which virtually identifies social reality with an ideology that has remolded all reality in its own image.

213

Once ideology — the abstract will to universality and the illusion associated with that will — is legitimized by the universal abstraction and the effective dictatorship of illusion that prevail in modern society, it is no longer a voluntaristic struggle of the fragmentary, but its triumph. Ideological pretensions take on a sort of flat, positivistic precision: they no longer represent historical choices, they are assertions of undeniable facts. The particular names of ideologies thus tend to disappear. The specifically ideological forms of system-supporting labor are reduced to an “epistemological base” that is itself presumed to be beyond ideology. Materialized ideology has no name, just as it has no formulatable historical agenda. Which is another way of saying that the history of different ideologies is over.

(http://www.bopsecrets.org/SI/debord/9.htm)

iiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiii

i don’t know how i feel

i feel kind of tired right now

when i get tired iiiiiiiiiiii feel bad or sometimes i feel weird and think things are funny

i’m listening to rick ross’s “teflon don” mixtape

trae is on this song

trae is from houston

trae has a really deep voice

i like his voice

he sings a lot on his songs

he raps fast sometimes, too

(i don’t know if you’re supposed to put a comma before “too”)

he’s in the screwed up click

there are a lot of rappers in the suc that have died

i feel kind of sad when i think of dead rappers

seems really sad

i can’t understand what that’s like

some people have dead brothers and sisters, dead friends

seems terrible

bad things happen to people, i guess

rick ross used to be a co

people talk about that

people think it makes him “fake” or something

seems like whatever

being a co probably pays alright and you don’t need a college degree

sometimes i think bad things about cops but seems like i shouldn’t

cops are just regular people and sometimmes do badd things

(rick ross just said “i’m a fat miotherfucker”)

i imagine some cops are sad and hate themselves

i can immagine doing sometihing terrible andd feeling terrible and wanting to kill myself but not killing myself

ii hope that never happens to me

i don’t want to have a hard life

i wast talking to my friend

(i only have one irl friend right now

the only other people i talk to are at work)

(oj the juiceman is on this song

i ilike oj the juiceman

he has two like “signature adlibs”

he goes “ay” and sometimmes “okay” in like a falsetto voice

he does it on like every song

seems really cool/funny

some of my other favorite adlibs are jim jones “BALLIN” and birdman’s bird sounds

i like it when people make gun sounds like “brrrrrrrrrrraaaaaat”)

my friend works at a restaurant

he works for just tipcs because the people who own the restaurant are fucking up their business shit

they owed like $1200 to a cook and wouldn’t pay her so she quit

my friend thinks they’re going to go bankrupt soon

he says that if they go bankrupt then we can hangout more

he works on the weekends and i work during the week so we don’t get to hangout much

i feel surprised that i’m doding okay righ now

i am alone a lot

in the past when i’ve been alone a lot i’ve gotten really sad

i go to work every day and talk to people at work, i guess

i sit at a computer all day and then come home and sit at the computer until i go to sleep

i probably spend like 12 hours a day on the computer

i don’t know if that’s bad or not

sometimes my eyes get red and hurt if i don’t get enough sleep

i try to get enough sleep

sometimes it’s hard to fall asleep

Good call. Oh, and sorry for distracting from the force and audacity of your post, Mike, but Althusser has a beautiful little essay on theater called “The ‘Piccolo Teatro’: Bertolazzi and Brecht

Notes on a Materialist Theatre.” You might really enjoy it. Here’s a quote that I think grapples with your subject matter:

“To return finally to my attempt at definition, with the simple aim of posing the question anew and in a better form, we can see that the play itself is the spectator’s consciousness – for the essential reason that the spectator has no other consciousness than the content which unites him to the play in advance, and the development of this content in the play itself: the new result which the play produces from the self-recognition whose image and presence it is. Brecht was right: if the theatre’s sole object were to be even a ‘dialectical’ commentary on this eternal self-recognition and non-recognition – then the spectator would already know the tune, it is his own. If, on the contrary, the theatre’s object is to destroy this intangible image, to set in motion the immobile, the eternal sphere of the illusory consciousness’s mythical world, then the play is really the development, the production of a new consciousness in the spectator – incomplete, like any other consciousness, but moved by this incompletion itself, this distance achieved, this inexhaustible work of criticism in action; the play is really the production of a new spectator, an actor who starts where the performance ends, who only starts so as to complete it, but in life.”

Read it here: http://www.marxists.org/reference/archive/althusser/1962/materialist-theatre.htm

Good call. Oh, and sorry for distracting from the force and audacity of your post, Mike, but Althusser has a beautiful little essay on theater called “The ‘Piccolo Teatro’: Bertolazzi and Brecht

Notes on a Materialist Theatre.” You might really enjoy it. Here’s a quote that I think grapples with your subject matter:

“To return finally to my attempt at definition, with the simple aim of posing the question anew and in a better form, we can see that the play itself is the spectator’s consciousness – for the essential reason that the spectator has no other consciousness than the content which unites him to the play in advance, and the development of this content in the play itself: the new result which the play produces from the self-recognition whose image and presence it is. Brecht was right: if the theatre’s sole object were to be even a ‘dialectical’ commentary on this eternal self-recognition and non-recognition – then the spectator would already know the tune, it is his own. If, on the contrary, the theatre’s object is to destroy this intangible image, to set in motion the immobile, the eternal sphere of the illusory consciousness’s mythical world, then the play is really the development, the production of a new consciousness in the spectator – incomplete, like any other consciousness, but moved by this incompletion itself, this distance achieved, this inexhaustible work of criticism in action; the play is really the production of a new spectator, an actor who starts where the performance ends, who only starts so as to complete it, but in life.”

Read it here: http://www.marxists.org/reference/archive/althusser/1962/materialist-theatre.htm

Good call. Oh, and sorry for distracting from the force and audacity of your post, Mike, but Althusser has a beautiful little essay on theater called “The ‘Piccolo Teatro’: Bertolazzi and Brecht

Notes on a Materialist Theatre.” You might really enjoy it. Here’s a quote that I think grapples with your subject matter:

“To return finally to my attempt at definition, with the simple aim of posing the question anew and in a better form, we can see that the play itself is the spectator’s consciousness – for the essential reason that the spectator has no other consciousness than the content which unites him to the play in advance, and the development of this content in the play itself: the new result which the play produces from the self-recognition whose image and presence it is. Brecht was right: if the theatre’s sole object were to be even a ‘dialectical’ commentary on this eternal self-recognition and non-recognition – then the spectator would already know the tune, it is his own. If, on the contrary, the theatre’s object is to destroy this intangible image, to set in motion the immobile, the eternal sphere of the illusory consciousness’s mythical world, then the play is really the development, the production of a new consciousness in the spectator – incomplete, like any other consciousness, but moved by this incompletion itself, this distance achieved, this inexhaustible work of criticism in action; the play is really the production of a new spectator, an actor who starts where the performance ends, who only starts so as to complete it, but in life.”

Read it here: http://www.marxists.org/reference/archive/althusser/1962/materialist-theatre.htm

That is, the materially same “word” has different meanings in accordance with each of its (immediate and mediating) contexts. (- perhaps because “words” shape the very contexts that, in dialectical turn, shape them.)

Yes, Henry, a common idea, an empirically compelled idea, perhaps an inevitable idea (though not, expressed by Mike, necessarily a ‘purely’ received idea). – an idea that could be used “ideologically”.

– but “pure ideology”?

The fact that “thought” isn’t (ever) private, certainly not linguistically mediated thought: this means that “thought”-that-happens-in-language “defines” its thinker as a matter of “ideology”?

“Ideology” is an Everything Word??

– certainly not for anyone who contrasts “ideology” to “scientific knowledge”.

Mike: Yes. Thanks so much for writing this deep and posting. This merits a few rereadings, but here’s a thought for now that I’ll come back to.

“I want THIS world to CHANGE.”

Weirdly, paradoxically, infuriatingly: archetypal narrative, shared story, is such a powerful motivator. Story and myth leads to so much action, or has historically. Now, funnily enough, in the West: traditional story dominates so much of entertainment, art, advertising, etc. Seems that this hasn’t changed since the birth of myth, but it has certainly perverted or made itself sterile (in that it inspires, here at least, very little action outside of routine/simple and non-violent ritual: e.g. religion, mass media). Art that focuses on affect is generally seen & propagated less, because it is more specific, less palatable, more difficult. It’s what, I’d say, a lot of us are trying to change. But those transition works: films like 2001, Antichrist, books like The Stranger… those are vital. They seem to feed from and pay out to both affect & narrative. Cohesive. Thinking about The Weather Underground: a lot of LDS/WU members talked about what lead them to be violent, to change this world… they speak about Vietnam and how it just made them feel CRAZY, out of control. That, to me, seemed like a interesting moment in time in that both grand narrative (death of civilians, citizens: parts of war) moved people, but moreso seemingly the total cacophony, the feel, the affect of chaos… that’s what pushed.

Thanks again.

It’s funny. I come from a background where “art” and “ideology” are almost always used pejoratively.

That Roche piece reminds me of Marinetti’s parole-in-libertà. Is there any connection between Tel Quel and futurism?

This is the first I’ve heard of that group, thanks for raking up interest.

alturl.com/q4f33

From what I know, there’s no connection (Tel Quel also seemed to not have any interest in surrealism either, though they were interested in Artaud, Lautremont & de Sade, but for the writing itself as opposed to the content [also not to intentionally draw a connection between futurism & surrealism, not sure why I just did that]). I think there’s a major possibility that Roche had seen some of the futurist graphic design stuff (which is arguably how I’d characterize Marinetti’s stuff–not derogatorily either), but their motivations are markedly different I think.

Is that background “the world where everything is ugly and terrible” ?

I think we’ve hit a point where the traditional story has lost its motivating factor… a cultural shift towards irony, I think, was a major part of sealing the casket of the grand narrative (see also: transition from modernity to post-modernism). I think that empathy just isn’t enough anymore. Part of the problem, I think, is that the traditional mode of storytelling relies on a passivity, a distance, and as we’ve carried on with that route being the mode of telling in a culturally homogeneous way for so long, empathy has become something totally divorced from a push towards change.

As a case in point, my mother, who watches a lot of daytime television, recently was talking to me about how the Ellen show or whatever had an episode on veganism (she was telling me this because I am vegan), and that they were showing like animal slaughter videos and she got like really disgusted by them. So I, naturally, was like “so are you going to stop eating meat?” She said that “no, she just wasn’t going to think about those videos,” which strikes me both as a typical (consumer based) response in this situation, but also potentially microcosmic of the hegemony at large.

i would not put a comma before too… i think you can, but it’s a mode of punctuation that bothers me for some unknown reason

I’ve got a copy of the Shaviro book, but it’s one among the many that sit on my shelf waiting to be read…

The Kant I’ve read gave me a headache, but I think I’ve encountered his theories of aesthetics via secondary sources; I’m not sure if I’m familiar enough to answer your question/suggestion, haha.

That Breton quote is brilliant, even though I have an inherent reaction to hate Breton and everything he says because he was a little power-hungry bitch, haha.

w/r/t Grandrieux, do you know KG? if no, perhaps message me on facebook about it

If you have not read Kierkegaard’s Either/Or, I suggest you do. This post is pretty much a missing (modern) chapter of A’s (the aesthete). Quite a few sentences seem like they could be placed right in the book without disturbing it. “The pleasure of the new” is a phrase that is probably literally in there somewhere.

i like that feels sincere

I think I have this problem which can probably be blamed on my admitted obsession with Bataille, where I think sometimes I try to write about things by writing outside of the things, but since I’m not doing it on purpose I don’t always ‘pull it off’ cogently, or something? Non-knowledge is a bitch. Or it’s possible that I am just saying this now in retrospect. I don’t.

But didn’t D + G establish that we are stuck within this system and we can’t get out of it? But then didn’t Hardt & Negri say “hey guess what we can get out of the system” ? I am asking, these are things I have heard but not read. What is the use-value of an ideology? Is it just a context? These are actual questions, and i’m hoping they don’t come off as cunty b/c I don’t mean them to be.

I haven’t read Althusser, and I haven’t read Marx directly, only indirectly (Very Short Introduction, Introducing, those intro books, etc). My political core is based on hating capitalism and loving freedom, and with freedom, pleasure. One thing I do think we need to escape is an ideology in which the idea of pleasure inherently ignores class problems, because I don’t think it has to be.

Well, I really have no basis for any response to your query about D +G – from what I’ve read, it seems that if revolution has a meaning for Deleuze at all, it is in radical immanence to the system, and cuts the system off from its own totalization and self-completion. Hardt and Negri’s answer is, likewise, that “the multitude” constitutes itself at the very same time that the State (constituted power) tries to extract a surplus from it, “act out” against it, etc. H + N argue that in fact the multitude generates its own surplus, the common, for control of which it struggles against the State in its current (“legal-biopolitical”) form. A typical instance is the antagonism over copyright laws, or what H +N call “immaterial production,” abstract production that collapses use-value and exchange-value, because it cannot be measured stricto sensu. H + N, as far as I know, aren’t theorists of ideology for the same reason that D + G are not – that is, because for them, the problem of how to constitute an extra-ideological space is not so much of a problem. The State is, for them, founded on the basis of “covering over” the common, which is ontologically prior to it.

It seems to me that an “ethics” of art might be substituted for “ideology,” or an ethics of pleasure, an ethics of sense. To respond to Chris’s suggestion earlier–that Kant could be a point of reference for you–Kant himself says in The Critique of Judgment that reason not only regulates sensibility but _dominates [Gewalt] it_. But contemporary philosophers have reread reason and its domination as an overdetermination or overwhelming of the “imagination” (which, I should add, as Chris unfortunately neglected to, is an extremely technical term for Kant) by the infinite. Or, by another name, that which is absolutely other to the constitution of experience, yet founds it. There is a fascinating dynamic and tension between those who think this thought, and the differential of its thinking: Jean-Francois Lyotard (the Kantian postmodernist), Jacques Ranciere (the political philosopher of aesthetics), Alain Badiou (the vaguely loony philosopher of “the event”), Catherine Malabou (probably the most exciting reader of Hegel alive). Just some material you might want to approach in thinking this topic over.

Well, I really have no basis for any response to your query about D +G – from what I’ve read, it seems that if revolution has a meaning for Deleuze at all, it is in radical immanence to the system, and cuts the system off from its own totalization and self-completion. Hardt and Negri’s answer is, likewise, that “the multitude” constitutes itself at the very same time that the State (constituted power) tries to extract a surplus from it, “act out” against it, etc. H + N argue that in fact the multitude generates its own surplus, the common, for control of which it struggles against the State in its current (“legal-biopolitical”) form. A typical instance is the antagonism over copyright laws, or what H +N call “immaterial production,” abstract production that collapses use-value and exchange-value, because it cannot be measured stricto sensu. H + N, as far as I know, aren’t theorists of ideology for the same reason that D + G are not – that is, because for them, the problem of how to constitute an extra-ideological space is not so much of a problem. The State is, for them, founded on the basis of “covering over” the common, which is ontologically prior to it.

It seems to me that an “ethics” of art might be substituted for “ideology,” or an ethics of pleasure, an ethics of sense. To respond to Chris’s suggestion earlier–that Kant could be a point of reference for you–Kant himself says in The Critique of Judgment that reason not only regulates sensibility but _dominates [Gewalt] it_. But contemporary philosophers have reread reason and its domination as an overdetermination or overwhelming of the “imagination” (which, I should add, as Chris unfortunately neglected to, is an extremely technical term for Kant) by the infinite. Or, by another name, that which is absolutely other to the constitution of experience, yet founds it. There is a fascinating dynamic and tension between those who think this thought, and the differential of its thinking: Jean-Francois Lyotard (the Kantian postmodernist), Jacques Ranciere (the political philosopher of aesthetics), Alain Badiou (the vaguely loony philosopher of “the event”), Catherine Malabou (probably the most exciting reader of Hegel alive). Just some material you might want to approach in thinking this topic over.

i’ve been working towards Badiou, but i feel like i want to finish my other philosophical/theory “projects” before I jump in there– similar with ranciere, though i feel like they probably intersect at points?

Lyotard is the only way that I’ve ever “read” Kant without wanting to punch my own face, and this is speaking strictly in terms of prose, not ideas, I guess. But, I didn’t carry on so I guess whatever I read was not too ‘exciting’ to me. (I should note that it takes me fucking FOREVER to read theory, so I mostly don’t read something unless it’s “exciting” in some way, I guess. That’s neither here nor there though)

I’m not sure what this means, but it is because I have an uneasy relationship with Kierkegaard & haven’t read Either/Or

thanks

This short little book attempts to explain the last 200 years of art as a super-category and its epistemological shortcomings in the context of “art for art’s sake.” Highly, highly recommended. Harris is a linguist by training, so his analysis is naturally colored as such, but it left me with a much better grasp of contemporary (mostly visual) art.

http://www.amazon.com/Great-Debate-about-Art-Paradigm/dp/0984201009

looks great, and it’s cheap. much thanks pizza.

i just bought both the Art Since 1900, as per Mike’s suggestions – dudeman those were expensive, but they do look really really good.

Either/Or presents a dialectic between two people, A and B. The first half is A’s portion, a collection of essays on various topics which illustrates his view of life (and art), which I believe mirrors very closely much of what you talk about in this post. This is over the course of 400+ pages, mind you… B’s portion is a rebuttal… of sorts, illustrating an alternative view, written in a different style. I was just saying that your post reminded me so much of the “A” portion that you could find some value in reading the book(s), or an abridged version (Penguin). A is the “aesthetic” view, B is the “ethical”, though it really doesn’t have to do with anything like “doing the right thing” or “morality” in that sense…

dear deadgod,

although i often find your googling skills impressive, and your pithy little comebacks enlightening, in this case, you are off base.

if you take the whole quote, instead of starting wherever it suits you, what i say makes more sense. although, i think it works both ways.

to not quote again what i have already quoted, m. kitchell says, in effect, I BELIEVE, INTENSELY, IN POST-STRUCTURALISM. it is a part of him somehow. this is how ideology works. it CREATES subjects.

if you had an idea what althusser means by “scientific knowledge” you wouldn’t be so goddamn smug, in fact, i think you might find yourself taking that extra google second to figure out what you are talking about next time, before you get crazy with the boldface know-it-all pose.

“Thus in order to represent why the category of the ‘subject’ is constitutive of ideology, which only exists by constituting concrete subjects as subjects, I shall employ a special mode of exposition: ‘concrete’ enough to be recognized, but abstract enough to be thinkable and thought, giving rise to a knowledge.”

—althusser

basically, he wants to acknowledge the difficulty of writing about ideology while within it, and in doing so, moves along with a series of “scientific” propositions.

for example:

“1. there is no practice except by and in an ideology”

cheers,

henry

Passivity in human experience is a topic I’m obsessed with right now, and I’m working on something that focuses on a lot of different films, a couple books, and a Q&A with the writer of taxi driver (really, blessedly, pretty much everything I’ve been experiencing over the past month has just been ticking off in my head, connecting up to this larger picture), and that tries to argue persuasively that people need to interact with media more, they need to do more than sit there. Whether it’s through the (largely academic, and therefore elitist/hard/contrived) enterprise of analyzing content (at various depths), or through the analysis of form/craft, or even just being able/willing to ask both during and after the “receiving” of art, “what is this doing to me? what does it mean? what do I have to say to this?” people need to think. The upshot of such a habit in people will be their demand for “good” work (“art”–something capable of freeing or liberating us, allowing/forcing us to think).

I guess I’m interested in why dumb people (passive; undeveloped in various senses) and smart people (active; learned; people who want to figure shit out) like different things, and how to get the dumb people to the point where they’re smart/active. I think the art itself, the experience of these works, can go a long way toward accomplishing that.

Your ideas here are vaguely familiar and yet very new to me, and because of this I can’t really say why I don’t agree with this idea that non-representation will cure our passivity. But I don’t. That is one of the things you’re saying, right? To some extent I think you and I are standing at the same point, but maybe we’re looking in two different (though not opposite) directions. I’m not sure what to think. I blame the threesome between you, deadgod, and henry; it made me forget what my brain thought.

I do agree about one thing though: traditional film bores me. I want something NEW, most especially because the new pretty much guarantees an avoidance of passivity. At the same time, I don’t think narrative is the only problem. For me, “narrative” is just so vast that it’s like, no way! The insistence on the traditional freytag’s pyramid narrative, no doubt, is one of the major problems with any art today I think, but getting rid of narrative altogether? I balk at that idea. But, again, I balk mostly because I don’t know enough about it yet, and because it cuts so sharply against my artistic sensibilities.

But anyway, what Grandrieux would you recommend I start with?

Henry, that sting you taste – someone else, “smug”?? – is called backwash. (For example, bold-type is no more intrinsically a “know-it-all pose” than is, say, the affectation of neglecting the routine capitalization of letters.)

It was wise of you not to engage with the point (about “ideology” being an Everything Word), just as it was wise of you ‘to miss’ the point of explicating Mike’s phrasing.

Your quick scroll through Althusser’s essay yields what Althusser calls a “thesis” about “practice”, a movement in “ideological representation” but towards science.

But look again at how Althusser talks, “in ideology”, as though he did have an extra-ideological point of view:

You see the difficulty? – how can “conditions of existence” more “real” than a “‘representation’ of the imaginary relationship of individuals” to them be posited from within such an ‘imagination’? indeed, accepting their own premise, how can the imagined-ness of those relationships be anything but yet another “ideology”, another scrim of “imaginary relationships” between “individuals” and . . .

Here’s how (I think) Althusser cuts through, or breaks out of, the circularity of calling all “relationship” to the concrete world purely “ideological”: he understands the “subject” (not the concrete individual) and “ideology” to be doubly constitutive:

Here’s a way to question the totality that you’ve quoted: to say that all “practice” is “by and in an ideology” is not to say that all concrete action is likewise “ideological”. Simply to declare that he’s using the word “practice” as constituted wholly by “ideology” doesn’t require Althusser to limit “individuals” to the “practices”, and therefore to the “ideologies” within which they ‘imagine’ themselves, each other, and “reality”.

Do you see, Henry, how the “knowledge” that Althusser wants “[to] giv[e] rise to” might be in contrast to what he himself understands to be “ideology”?

A word for this “knowledge”, and for the social world in which an “individual” might not always already have been interpellated by “ideology” as a “subject”, is: revolutionary.

Cheers to you, Henry.

dear deadgod,

your response is exactly what i meant by a know-it-all pose. it’s not just the boldface, it’s the way you act as if you know everything. although i don’t always post on HTMLGIANT i do read it often enough. comments also. and you are someone who acts as if s/he knows everything. that’s why i reference your know-it-all pose. not because of the bold stuff. it’s cool if you can convince some people that you actually do know everything. obviously that is of great importance to you. in any case, i’m glad you seem to have actually taken the time to read at least some of the essay i linked to. i mean, that’s all i really wanted anyone to do. i never claimed and still do not claim to Know everything or have any special knowledge about ideology or this text in general. but i still maintain they are important things to think about. that it is important to have more than a dictionary.com type def. of this field.

i have honestly no idea what you mean by an EVERYTHING WORD. i don’t even know where to start. but hey, if you can explain yourself a bit more then we can talk about that.

i explicated mike’s words and related it to the essay in question. then i tried to translate it in a way that someone who didn’t read the thing would understand (for your benefit, if that is not clear, because at that point you obviously had not read it)…so what is your point? make a point and i will address it.

again, you take excerpts out of an essay to try and make a point that simply is not there. i mean, you can understand the essay and ideology however you want. i understand the process of taking quotes out of context. so cool. go for it however you want.

i do, in fact, see the difficulty of the situation of trying to talk about ideology from a standpoint, as a subject, who has been created by ideology. if you can’t remember that far back in time, scroll up. i brought this problem/part of the essay to your attention, not the other way around.

but what’s funny, really, is that most of the time you think you are making a point that disagrees with me, but you aren’t. you are just parroting what i said and acting like you said something different (except for your asinine conclusion). so go on with your boldface self and preach the gospel. i’ll be your christ if you need one.

but about that conclusion,

“A word for this “knowledge”, and for the social world in which an “individual” might not always already have been interpellated by “ideology” as a “subject”, is: revolutionary.”

please explain this mess of hopefulness based on the essay in question or in general at all.

but hey. words are symbols and an endless chain of signifiers and everyone that can use boldface and google is an expert on everything. it’s 2011, man.

love,

henry

I’m not 100% sure I follow your assertion, Alec, that for Kant “reason not only regulates sensibility but _dominates [Gewalt] it_.” If I’m reading you correctly, you are arguing that Kant argues that reason (logos) dominates sensibility (pathos), which does not correspond to my understanding of Kant at all. In fact, just the opposite…

When discussing “the beautiful” and distinguishing it from “the good” and “the agreeable” Kant says (for the sake of everyone being able to find the source, I’ll quote it from the Norton Anthology of Theory & Criticism rather than my specific edition of The Critique of Judgment):

And then, a little later, he says:

It’s the beauty of the beautiful, really, that seems to be the crux of Kant’s aesthetic theory. Ethics is not at issue. For Hegel, yes. For Hegel aesthetics would be all about the ethics, for sure, but my reading of Kant suggests that ethics must necessarily be divorced from aesthetics. Art for art’s sake. Pleasure. Pleasure. Pleasure. Etcetera.

Also, when you mention the “overdetermination or overwhelming of the “imagination” by the infinite” I can only assume you’re referring to Kant’s discussion of the sublime, not his discussion of the beautiful. These are separate arguments. Truth be told, I’m uninterested in the sublime. It’s Kant’s discussion of the beautiful that interests me, and it is also where I think Kant has something in common with Mike’s post here.

I hate to continually pimp books by Steven Shaviro, but he has another great book called Without Criteria: Kant, Whitehead, Deleuze, and Aesthetics, at the beginning of which he sets out a nice precis of Kant’s argument about “the beautiful.” Worth checking out, for sure.

I don’t know what you mean by “acts as if”, Henry. I say what I think is true or fair. You mistake a willingness to risk a perspective for a confidence that ‘failure’ is impossible, which is, to be sure, illuminating.

Nobody has argued against your brave stand that a single definition of so complex and multivalent a term as “ideology” is adequate. It was you who entered this conversation by stating, without argument, that somebody else “do[es]n’t know what ideology is”; you’ve since “maintain[ed]” that you want more discussion than a dictionary definition, and now you persist in a simplistic reading of Althusser’s “ideology”, and use a couple of sentences to defend your simplification, positions whose limits are somewhat the point of the essay you’ve skimmed.

I “explicated” Mike’s wording – your “paraphrase” is too one-sided to stand as ‘explanation’ – , in order to say that, while the linguistic mediation of thought might be always-already “ideological”, nevertheless, thought is not trapped in a prison of “pure ideology”. That is, the term “ideology” (for example: in Althusser) does not exhaust, nor does “ideology” negate, the capacity of thought to disclose to itself “reality”. That is a commitment of Marx’s that Althusser shares, as one can plainly see when Althusser uses the word “reality” unironically.

Your presentation and hand-wafted defense of the essay’s two sentences that leaped out at you is just the right context for your ‘understanding’ of decontextualization.

You did indeed bring up “the difficulty of the situation of trying to talk about ideology from a stand point, as a subject, who has been created by ideology”; I didn’t signpost your remark in response to it because I thought, correctly, that that’d be condescending. I should have, anyway.

– but you brought up this difficulty as a last word, your quotation doesn’t lead to the conclusion you’ve hedged, and (I think) it was my ‘linguistic-mediation’ phrasing that clarified for you the possibility that “difficult” isn’t the same as ‘impossible’.

Henry, I think (one of) the point(s) Althusser is making in the essay is that, while “ideology” seems to envelop all thought from within – especially thought about “reality” and about thinking about “reality’ – , in fact, there is, in thought, the actuality of “reality” that stands intelligibly over against our minds’ “subjection” to “ideological representation” of our “relations” to “reality”.

Here is a way to see that what I’m saying is no mere sophistry: Althusser uses the terms “concrete”, “reality”, “knowledge”, and “scientific knowledge” in his “ideology” essay without irony or qualifying skepticism. Have a look! These words are not magical dissolvers of “ideology”, but neither are they used in a way trapped in the self-reproducing circularity that is a (the?) function for “subjects” of and to “ideology”.

I’ll ask you again, Henry: this “concrete” “reality”, and the “scientific” “knowledge” of it – how does Althusser refer to these in a non-naive, non-self-canceling way? Does he not argue that, while he’s writing “ideologically” and as a “subject”, he’s also writing, what, ‘towards’ the evolution of the ideological production of the subject into the discourse of a concrete individual?

—

You repeat your accusations of “googling”, “know-it-all”, “taking quotes out of context”, and “parroting”; these are unwisely indulged “signifiers” for you to wield, Henry. I say this out of love: best leave sarcasm to the pros.

—

Right after the thesis (that you called a “‘scientific’ proposition”), there’s a section called “Ideology Interpellates Individuals as Subjects”. (Really! – have a look.) Your amber-“ideology” is what Althusser calls an “ideology of ideology”; the essay is getting at, or towards, a “theory of ideology”, one that would be conceived by an “individual” not “interpellated by ideology as a subject”. – in a phrase: a revolutionary individual.

my suggestion is that we take this private. there is no point in deliberately misrepresenting things if you are just emailing me and not making a pose for the general public (henry.vauban (at) googlemail.com).

but i will attempt, for a last time, to respond to your opinions and accusations.

“Nobody has argued against your brave stand that a single definition of so complex and multivalent a term as “ideology” is adequate”

i suggested starting with this althusser essay. a good place to start, i think i said. i didn’t say it was the end. i didn’t say i love it and agree with it 100%. in fact, i suggested that the single definition of ideology in play was fucking worthless…but yes, i still maintain that using the dictionary def. of “ideology” is kind of weak in 2011. it shows that the writer is at least 40 years behind the curve. how would you define, say, ontology, then? the study of being?…

the reason i only pointed out a couple points in the essay is because you obviously had not read it, but you were pretending to know it at some kind of expert level. i called your bluff. i wasn’t trying to summarize the whole thing for your benefit with a couple of quotes, although looking at the situation now, i should have summarized it for you.

“thought is not trapped in a prison of “pure ideology”. That is, the term “ideology” (for example: in Althusser) does not exhaust, nor does “ideology” negate, the capacity of thought to disclose to itself “reality”. That is a commitment of Marx’s that Althusser shares, as one can plainly see when Althusser uses the word “reality” unironically.”

althusser uses the word “reality” in a common unthinking way, because fuck, what should he call what he is trying to contrast with ideology other than reality. i never disagreed with the idea that althusser is trying to contrast ideology with some other “scientifically” based reality. i have already said this before.

but for people who don’t know what we are talking about here, SCIENCE, for althusser is clearly still ideological. the science he is talking about is not like math of physics (not that that wouldn’t also be ideological). he is just trying desperately, in his french way, to have a method with which to confront ideology while within it, acknowledging his debt to it, so to speak. if you don’t agree with that, ok. that’s fine. that’s your reading. but i don’t agree with it and i don’t think that is what althusser is trying to get at.

if you read the thing a bit closer, you will see that he is distancing himself from Marx’s view, not seconding it. he says that rather explicitly. with examples.

he is saying that ideology has a REALITY, materially speaking.

here is a quote you might want to think about:

“The writing I am currently executing and the reading you are currently performing are also in this respect rituals of ideological recognition, including the ‘obviousness’ with which the ‘truth’ or ‘error’ of my reflections may impose itself on you.”

and here is the whole “ideology of ideology” quote for those confused by deadgod’s misrepresentation above:

“In every case, the ideology of ideology thus recognizes, despite its imaginary distortion, that the ‘ideas’ of a human subject exist in his actions, or ought to exist in his actions, and if that is not the case, it lends him other ideas corresponding to the actions (however perverse) that he does perform. This ideology talks of actions: I shall talk of actions inserted into practices. And I shall point out that these practices are governed by the rituals in which these practices are inscribed, within the material existence of an ideological apparatus, be it only a small part of that apparatus: a small mass in a small church, a funeral, a minor match at a sports’ club, a school day, a political party meeting, etc.”

but maybe this helps more:

“I shall therefore say that, where only a single subject (such and such an individual) is concerned, the existence of the ideas of his belief is material in that his ideas are his material actions inserted into material practices governed by material rituals which are themselves defined by the material ideological apparatus from which derive the ideas of that subject.”

but it’s cool, i think, this whole conversation is cool. i mean you went from being someone who had never read this essay to someone who has read this essay and is willing to defend his/her readings to the last breath. i couldn’t ask for more. i just hope that not too many people were turned off of the subject by our puffed up little back and forth.

love,

henry

Still clinging to the ‘hadn’t read it yet’ meme, Henry? – only now with extensive quotes to demonstrate your skimming skilz! That’s lovely.

It’s still true that nobody’s arguing for a narrow definition of ideology, or to an end to discussion about it, but, once again, you pantomime a roundhouse to win the point.

You “pointed out a couple of points” that didn’t respond to the issue of how to grasp the universality of “ideology” from within it – that is, perhaps “ideology” is not universally human, but rather is endemic to concrete individuals who are interpellated by ideology as subjects, concrete individuals ‘established’ as “ideological subjects” (a tautology, in Althusser’s view) within political economy – . Indeed, you figured out that Althusser “wants to acknowledge the difficulty of writing about ideology while within it” – except without realizing that the essay would “dare to be the beginning of a scientific discourse on ideology” by being a step on the way to a “break” with “ideological representations” of “subjects”.

Rather than rephrasing your skimmed nuggets, you should have summarized the whole essay.

Of course Althusser “is trying to have a method with which to confront ideology while still within it, acknowledging his debt to it, so to speak”. I do agree with this “reading” – why, it’s my own! – that’s a “summary” of the near-concluding quote I’d taken from the essay and presented two (of my) posts above, so you didn’t even have to hunt-and-peck for it! (You contribute another quotation to similar effect – good skimming!)

– but there’s still the problem of Althusser talking about “ideology” as though his talk would mean something – as though what he’s saying can’t be dismissed as, well, just ‘more “ideology”‘. Althusser does not “use ‘reality’ in a common, unthinking way”; he uses it – and “concrete” and “scientific knowledge” – in contrast to “ideology”. His scientificity is “ideological” – but he is committed to a ‘scientifically discursive’ “break” with persistent-but-not-permanent “ideology”.

Althusser’s take on Marx is that there’s an ‘early’ and a ‘late’ “Marx”, that the progress – and its movement is ‘progressive’ – of Marx’s thought is from quite “ideological”, quite bourgeois, towards the “discourse of a concrete individual” – ‘towards’ without arriving, without a correlatively concrete world free from political economy.

The reason I think your view of Althusser’s “ideology” is – rather: might be a part of – an “ideology of ideology” is precisely that your view is that (Althusser’s) “ideology” is inescapably necessary. A “theory of ideology” would be, in Althusser’s terms, not a circular Everything Claim, but rather, the “discourse of a concrete individual”.

I see that the materiality of “ideology” is a great discovery in your most recent skim of the essay; this materialism doesn’t affect our difference of opinion about Althusser’s self-understanding of the “ideological representation” still characterizing his attempted “break” into a “discourse of a concrete individual”.

I hope you give Althusser’s take on “ideology” a close look; as you guess, it’s worth it.

Cheers.

It’s probably easiest to start with Sombre, as it’s the most narrative and will help you sort of orient yourself to how Grandrieux uses images. And then basically just go chronologically to La Vie Nouvelle & Un Lac which I still haven’t seen actually.

Well, I don’t like the word ideology or ideologies themselves. I’m with you on the experiential focus, but my take on it is different. My experience of being in therapy has resulted in me not really caring about or liking judgments, knowledge, etc. So I tend to value the bare experience of life more, and that’s also what I value in art too. For example, I’ve written about the rape scene in Hitchcock’s Frenzy (http://www.journeybyframe.com/2010/09/23/frenzy-alfred-hitchcock-1972/), which I think is really interesting because it’s so viscerally present and vivid, and it doesn’t even take time to condemn the act itself (why should we need him to condemn something universally detested?).

But I don’t really dislike empathy, although I don’t really use that word or have any use for the concept. I think what’s more important than experience, which is firmly “subjective,” for me is intersubjectivity, an interconnection between art and viewer/etc. I think I have fewer boundaries than you about what art is good and what is not, or maybe I’m just not aware as much as you are. But I don’t think a work of art needs the proper form to create that intersubjectivity, that bare connect/experience between two beings (excuse the term). I find it in a lot of different places, because I think it transcends the content/form dichotomy, which I’ve always found lacking. Somehow, I think art is about a connection between oneself and the rest of the world, the artist, etc.

Another “value” I find really important in art is nakedness, vulnerability, honesty, etc. I don’t know how to slot that in to this. So I guess I’m saying I’m with you in some ways, can’t figure out other things, and maybe think differently about other things.