Bath

Things that happen in the bath.

Things that happen in the bath.

This is going to be long. I will discuss politics in the dangerous context of business and try to compare Seattle and New York, but I will go astray. You’re warned. I spent a long time to fix the structure of this essay. This first bit is about my vocation and leads into a bit about leaving New York. I think I wanted to give the political parts a level of context. It’s hard to read about politics if you don’t know what it comes out of.

Russia won the US Elections, white supremacists/fascists/military dictators toasting their BFF heart necklaces in a pyramid scheme, DAPL accepting donations for legal sanitary and emergency purposes, high school students and college students demand sanctuary cities and sanctuary campuses as sites of refuge from fascists, McCarthy-era Submit a Tip watch list compiled by a herd of Sound of Music golden Trump Youth a.k.a Turning Point, families torn apart by white nationalist swamp monsters, Obama somehow became the nation’s First Therapist, deportation trauma continues to swirl, more islands disappear into wrathful unforgiving waters, refugees have nowhere to go despite this one planet, endless slavery and the incarcerated state, $50k Thnxgiving dinners for 8 in Manhattan which is about the same average of graduate student debt in education, science, and arts, the undying click holes of inertia (dance with me, won’t you?), scam universities, the fake news problem, scam everything, the doctrine of legitimacy, elephants still being trained to paint, dolphins be painting too, paranoia as wish-fulfillment, unaffordable Buddhist retreats, warmer degrees, the rising tide of far right conspiracy theory cults, State says literacy is not a right in Detroit, while NYC to spend 1 million per day on Trump security, and a few days ago in Chicago Angela Davis reminded a crowd that “community is the answer.”

Riding high and feeling low, I went to meet and spend time with the daughter of a fiery psychoanalyst-philosopher, militant, and experimental reformer of psychiatric care in postwar France. I wanted to meet Emmanuelle Guattari without needing to exactly know why. I’d been carrying around her minty green slender novella “I, Little, Asylum” (translated by E.C. Belli, Semiotext(e), 2015) for over a year in my backpack and using a mechanical pencil to write: with, through, beside, throughout, in spite of, without, within, around, marginally, above, underneath, over, and between her book. Basically, these self-help strategies or sun salutations by which to: include, insert, mirror, and assimilate myself into this text were just ways of tricking myself into merging parts of my childhood with hers. (The desire to merge my experience with her experiences in her novella I’m saving for longer daydreamy semi-catatonic spells in bed or in a bath.) Essay. Sail. Essay-sailing. Essail. A noticeable season went by and suddenly I found myself meeting Emmanuelle in an eastern-suburb of Paris on a drizzly day slipping and sliding on the slick scales of Libra; the seventh sign of the zodiac where things shift from “personal focus” to “contact with others and with the world”. Good, makes sense. I took off and went for her like searching for a lost fraternal twin who grew up in a house of madness and maniacs halfway across the world – except in a castle. While I read her book I thought she was describing the Residents I lived with for eleven years except there weren’t any Residents in her book. I was projecting. But how else are you supposed to connect to anything without a little projection? There were Residents everywhere in her book, I swear. The mind has a sneaky way of cutting and pasting, of collaging, of transference doing somersaults in the most untrained way possible.

We met (it felt like a secret) in a working class strip mall at the Montreuil Station and I recognized her right away only because I saw an interview of her online. I approached her, said hello, and hurriedly she welcomed me with a kiss on both cheeks and took me under some invisible wing as we walked through roasted peanut smoke filled swap meats, in and out of cafes, until we made a full circle and settled in a brutal-banal coffee shop tucked in the strip mall we initially tried to get out of. It felt right because of my love for certain kinds of strip malls; giant transparent posters of coffee and sandwiches on the windows. It felt especially right because she did not know my love for them. And so it was “un-homely” as the Germans say. But also that feeling of un-homliness or whatever was totally perfect for all of its (un)familiarity because of what we were about to talk about: vague notions of crisis heterotopias, board and care facilities in Los Angeles where I grew up, and the La Borde hospital outside of Paris where she grew up. We put our coats and bags on a table to save it, kind of pretending that suddenly it would get busy in there. I was too shy to order something substantial to eat like a plain croissant when she kindly offered to treat us. So I pointed at the green grapes in a plastic container and asked for black coffee. Emmanuelle was a little curious about why only green grapes. I could be imagining this now, but there was nothing symbolic at all about the grapes. It was just something easy to eat while asking her questions. Something to casually pop in my mouth between answers and eye blinks and occasionally staring out the window. Some of the grapes were a little soggy but I ate them devotedly.

In the following weeks I’ll be posting parts of the interview.

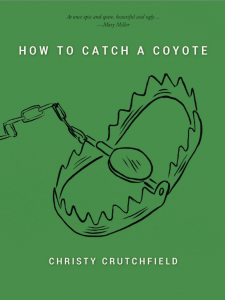

How to Catch a Coyote

a novel by Christy Crutchfield

Publishing Genius Press

208 pages, paperback, 6 x 8″

ISBN: 978-0-9887503-8-8

July 29, 2014

Within minutes of pre-ordering How To Catch a Coyote by Christy Crutchfield, I was handed an ARC by its publisher, Adam Robinson. I began reading it in a dentist chair (which is definitely a kind of bath, hence the category label on this post) and finished reading it a day later, at the expense of all other work, so absorbed was I in this multivalent narrative of many years in the life of a very difficult family. Sharp cuts in chronology and a kind of chill resistance to poignancy and emotiveness distinguish the novel from the many that expect our empathy or identification as a matter of course instead of asking, as this book does, whether we can possibly empathize or identify with these characters, and what that even means, and whether we even want to.

I was about to get a filling replaced because one fell out and left a hole with a sharp edge that trapped little bits of whatever I was eating no matter how much I tried to chew on the left side only. This turned out to be a great place to start reading How To Catch a Coyote because it is full of teeth and traps.

When I typed multivalent narrative above, which was an edit of the hackneyed layered narrative, what I hoped I meant was from many angles since the book shifts among second and then mostly close third-person POV, but close to all different characters. It turns out I meant nothing of the sort, since multivalent actually means having or susceptible to many applications, interpretations, meanings, or values. This is much more to the point. The POV, the dips and skips of chronology, and other formal devices that you’ll see for yourself are not, IMO, the thing this novel is, though they certainly incandesce around and expertly minister to the thing that this novel is. The thing that this novel is is, is the susceptibility of it, of us, of the characters in the face of not knowing for sure.

No spoilers! I want to wait until you’ve read it to talk about it more. This novel is very very topical, and it will be topical forever or at least as long as there are fathers and daughters, and mothers and daughters, and fathers and sons, and mothers and sons, and–most crucially, I would hazard, but we can talk about it more–brothers and sisters (bcc: Ronan Farrow or does that give too much away?).

Pre-order this book so we can all talk about it a lot. I think it would be a really good book to talk about with college students, and I think it would be a really good book club book, too. Adam and I discovered that we had diverging takes on a single sentence, is how much there is to talk about in this book. I can’t wait until all of you read it!

I read Scarecrone by Melissa Broder in the bath. Originally, I bought every copy of Scarecrone from Adam Robinson but then I sold them all back to him for the same price, except one, which I kept. That is the copy of Scarecrone I read in the bath.

I had a notebook and pen by the bath because I knew it would be an experience that I would want to express something about, even though I’m uneasy with experiences and expression.

Earlier, I’d read an interview of Melissa Broder by Shane Jones in The Believer about food and food rituals. The interview answers are very honest and detailed. I became upset as I read it because it put me in touch with a kind of radical normalcy in my thoughts and behaviors around food and my body. I began to wonder, as I’ve wondered before, if that normalcy has to do with how many hours & hours I spent in the bathtub as a child and teen, around my own naked body but not confronted with it. As a child and teen, in the bathtub, I usually either read, in which case I saw my headless naked body in the lower periphery, or I did things to make my body feel or do things, in which case I guess I closed my eyes or saw my body through unusual filters.

(I don’t know how to describe any of this in non-dualist ways, especially from the bath point of view since–unlike in the mirror where you see everything or mostly your face– in the bath you see your body but not your head where your brain is, so that the body really seems like something apart.)

I thought about how I have no discipline about food–no habits–but I do have a modicum of self-control. A lot of the interview was about bingeing, which I’ve never done, and which must require even more discipline than purging or limiting food. Bingeing must require a kind of vision, or drive, that will only work via an extreme amount of discipline that I’ll never have.

I thought about how uninterested in purity I am, especially when it comes to food and the body, which is part of what upset me about the interview. I have been slow to read Scarecrone in part because it seems pure and honest, and I am uncomfortable with purity and not very honest. Part of that dishonesty has probably led me throughout my life to deny the existence of any bad feelings about my body. Shame itself is so pure, or at least it’s predicated on the desire for purity. I am not honest about shame I might feel, or ways that I might wish I were pure or that something in the world were pure.

Still, I wanted to read Scarecrone in the bath. I thought something would happen to me if I did because I read reviews that said it is a book of spells, and I am most vulnerable to spells in the bath. I ran the water and realized it was much too hot. For the spell to work, I thought, maybe it would be better to sit naked on the cold toilet seat beside the bath but not get in, and read Scarecrone like that. Or maybe for it to work I should light candles and put them around the bath.