The Collaborative Workshop

A few years ago, when I moved from L.A. to Kansas and began my dizzying transition from grad student to faculty member, I dug out of my closet the stacks and stacks of workshop manuscripts of my early efforts. There they were: fifteen copies of every lousy draft I’d produced, each decorated with marginalia and scribbled endnotes. Sometimes whole paragraphs were blacked out, as if my classmate were an overzealous FBI agent releasing my story under the Freedom of Information Act. Sometimes a poignant protest “No!” would appear to tumble through the white space, alongside a disappointed “You know better!”

Some of these notes were ten years old, but as I looked at them again, the nausea was fresh in my throat. There were hundreds of these, representing my years in an MFA and then a PhD program, contradicting each other in a cacophony of criticism and praise, some written by people whose faces for the life of me I could not remember. It took several trip down two flights of stairs and across a parking lot, but I tossed them all into the apartment complex dumpster. Good-bye to all that.

“A Dozen Dominants: The Current State of US Indy Lit”

[Update: Some reader comments below prompted me to write a follow-up post.]

I was asked over the summer to contribute a critical article to the online UK journal Beat the Dust; they wanted me to write on the current state of US literature. I “narrowed that down” to indy lit (small press publishing, whatever you want to call it)—still an impossibly huge topic, of course. So I ended up proposing twelve dominants that I’d argue govern the current indy lit scene (at least as best as I can see things from where I’m sitting—Chicago, USA, 2011).

“Dominant” is a term I stole from the Russian Formalists; it essentially means a feature or aspect of a text that most people feel that the text, to be valid, should demonstrate or otherwise include. (e.g., rhyme was often a dominant in English poetry until the 20th century and the advent of free verse; now the situation is mostly the opposite.) (See also this.) Below, I’ll list “my twelve” dominants, but please see the full article for a more thorough explanation…

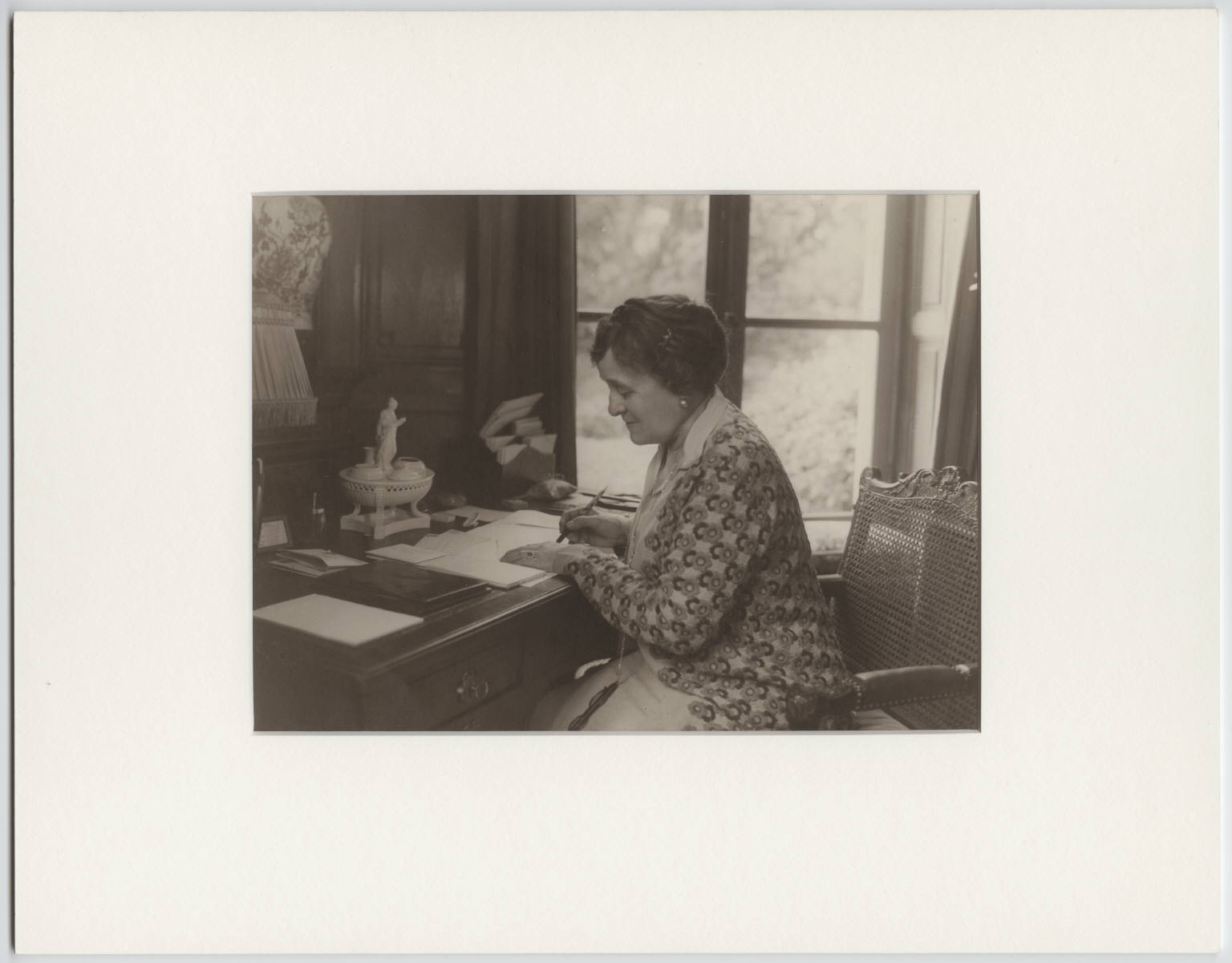

Class Is in Session With Professor Edith Wharton

Edith Wharton is one of my favorite writers. Her stories are timeless and elegant and if I had to be trapped somewhere with only one writer’s books for the rest of my life, I’d probably choose the complete works of Edith Wharton.

I’ve been thinking about Edith a great deal lately because I’ve been having a lot of self-doubt about my writing for a number of reasons, few of them rational, all of them frustrating. The Internet is great but it’s also terrible because you know, all the time, what everyone else is doing and it’s easy to lose sight of writing itself as what matters most. It’s not hard to fall into the trap of losing confidence in what you do as a writer and/or trying to keep up with the literary Joneses by writing outside of your comfort zone to respond to the literary zeitgeiest. The older I get, the more I realize that while you can and should grow and challenge yourself as a writer, you can only be who you are. Sometimes, like many writers, I lose sight of that. I recently consoled myself with Age of Innocence and Wharton’s amazing short story, “Copy: A Dialogue.” Then I read Wharton’s The Writing of Fiction, a slim but rich volume of writing on writing. Wharton’s insights are sharp, timeless, and truly invaluable.

39

Interviewer: How much rewriting do you do?

Hemingway: It depends. I rewrote the ending of Farewell to Arms, the last page of it, 39 times before I was satisfied.

Interviewer: Was there some technical problem there? What was it that had stumped you?

Hemingway: Getting the words right.

(Ernest Hemingway, “The Art of Fiction,” The Paris Review Interview, 1956)

Reflections from a Shiny New Creative Writing Teacher

I’m writing this in between grading my (first ever!) students’ second poems. I’ve been teaching for about a month.

One of the first things I learned about teaching: grading takes an ungodly amount of time. There are several steps, which include:

1. Excitedly read through first batch of student poems on the bus home from class.

2. Read poems at home.

3. Read poems aloud to roommate (also a teacher) to make sure you’re not missing something.

4. Write comments on poems in pencil.

5. Worry comments are too prescriptive.

6. Erase comments and try again.

7. Agonize about putting numbers on poems.

8. Briefly consider flaunting university guidelines and not grading poems.

9. Put numbers on poems.

10. Reread poems and compare grades.

11. Hope students read comments instead of just staring at their grades.

A Little Bit More on Cliché

Here’s the plot: a woman sees this guy and falls in love. The trouble is, her father is feuding with the fellow’s father.

Sound familiar?

OCEAN NOTES

several days ago i stayed up all night watching the ocean and telling myself that i will never go back. i felt that after that moment, everything would have to be different. i finally get it. i finally understand what it’s all about. i see everything now and i know what decisions must be made. what have i got to do to not forget this lesson? to not lose contact. in a few hours i will be zipped across this very sky on a plane en route to baltimore. i will ride it for free using the complimentary ticket i got when i wrote and faxed a four page complaint to american airlines—faxed so i could bypass the word limit on the website form (who said writing skillz aren’t practical?). i am afraid. i know that in baltimore i will not have the psychic or physical space to really sink into it and i’m wondering—does being around people desensitize you, force you onto a different wavelength, flatten your really intense visions and impulses? BECAUSE IF I AM TO WRITE I CANNOT BE DESENSITIZED. how am i going to write these books? to think, several days ago i was at the end of my life laughing, watching the waves crash into the rocks as the world expanded in every directions all around me. i was on this extremely long and lonely journey just to figure out that everything would be okay, and when i came to this realization everything suddenly opened up. i was inside my life in this totally different way—for the first time i wasn’t wishing i were somewhere else; wasn’t wishing i were smarter, better or more like this or that. mid-revelation a cop pulled up, parked his car, and stared me down. he wouldn’t leave. fuck that cop. and all other cops. you’re cramping my style. i stumbled away from the cop and into the gaze of a pack of drunk guys. they started yelling sexual comments at me and began to walk toward me. i was preparing myself to fight and was convinced i could take all of them down. just then my little brother and his friend showed up.

&NOW Tomorrowland Forever & The Mad Science of Narrative

This past weekend (Thursday – Saturday) was the &NOW Festival of New Writing 2011 (Tomorrowland Forever) at UC San Diego. I planned on writing a more cohesive write-up of the conference, but the condensed intensity of the conference (in the most positive way possible) has exhausted by brain and I may need a bit of a recovery period to really process all the stimulating conversation and events. So much thanks and to Anna Joy Springer and Amina Cain for putting on such an awesome event.

On one of the panels I was a part of, “The Mad Science of Narrative: Temporal Horizons and Neurological Transcendence,” we 4 panelists (loosely operating as the collective Strophe) continued to explore some themes we’ve been talking about for some time now, surrounding issues of narrative & narrativization. Some really amazing & productive conversation ensued, and we hope to keep this conversation going, so in hopes of that, am posting up our mini-papers here (which we presented first and then opened up for general discussion). My own paper is largely recycled from some other things I’ve also been working on, as these ideas have largely been shaping my critical & creative practice as of late. Anyways, looking forward to hearing more thoughts.

FictionSpeak 2: Dialogue

I was trying to write dialogue the other day. Then I was trying to write about dialogue. There was an article in the Wall Street Journal back in February called “Talk That Walks: How Hemingway’s Dialogue Powers a Story,” by John L’Heureux. I found this article because I had just read “Hills Like White Elephants.” I don’t feel like talking about Hemingway. Though his dialogue is masterful, I really hate his treatment of the girl. I also hate L’Heureux’s treatment of the girl for different reasons, but I like what he says at the conclusion of this article:

“Dialogue suggests what people mean by what they’re saying, even if they themselves aren’t fully aware of it. Sometimes, of course, the most effective dialogue culminates in silence. This is more than irony. It is what characters do to one another.”

Because the writer is god, she knows what her characters mean. I don’t know about that. I like Silence. I’d like to know about un-dialogue please. When I was thinking about dialogue, I started writing this:

What is dialogue but the memory of nothing-ever-said? How many palettes from which to choose? You say this, you dothisthingtome. I say something back, which is worse in my mind than knifing a dying dog. I want to write about a conversation had. A once-had conversation. But it’ll never work. Nothing works but the working, someone said, out of darkness. Nothing but the eventual loss of a thing. Loss of a pain, loss of a memory. Is it or is it not the same face on the coin? The same face before bed beckoning.

I wake up angry. Wanting a fight. Which I’ll never get, which you’ll never give me. Ever-heaver. Ever-body-distiller.

Dialogue is a thing we do in stories. Or a thing smug people do in offices with bright lights.

“Let’s have a dialogue about this.”

“Fuck you.”

And then the piece turned into something else entirely. I was trying to teach freshman writing students about dialogue a few weeks ago, and I gave them a bunch of revision checklists. I asked questions of them like, “Is the dialogue natural? Does your dialogue portray personality? Is your dialogue interesting? [what does that mean?] In class, we’d read “Hills Like White Elephants” aloud. We talked about mystery, about saying, not saying, about how things are said. I didn’t teach these kids a goddamn thing, though a few of them caught on.

My question is this. I don’t want dialogue. I want not-dialogue. What are the best books that make minimal but insanely good use of dialogue?