Ted Bundy on Writing

“The fantasy that accompanies and generates the anticipation that precedes the crime is always more stimulating than the immediate aftermath of the crime itself.”

“I don’t want to beat around the bush with you anymore. I’m just tired.”

“I’m no social scientist, and I don’t pretend to believe what John Q. Citizen thinks.”

“It was like coming out of some horrible trance or dream. I can only liken it to (and I don’t want to overdramatize it) being possessed by something so awful and alien, and the next morning waking up and remembering what happened and realizing that in the eyes of the law, and certainly in the eyes of God, you’re responsible.”

“I went down the road, throwing everything I had, the briefcase, out the window. Throwing the briefcase, the crutches, the rope, the clothes.”

“You take the individual we are talking about and then you subject him to stress. Stress happens to come randomly, but its effect on the personality is not random; it’s specific. That results in a certain amount of chaos, confusion, and frustration. That person begins to seek out a target for his frustrations. The continued nature of this stress this person was under — the nature of the flaw or weakness in his personality, together with other elements in the environment that offer him a logical target for his frustrations or escapes from reality — yields the situation we’re discussing. There is no trigger, it is truly more sophisticated than that.”

“Possessing them physically as one would possess a potted plant, a painting, or a Porsche. Owning, as it were, this individual.”

“I’m talking about going beyond retribution, which is what people want with me.”

“Countless millions who have walked this earth before us have gone through this, so this is just an experience we all share.”

“I just liked to kill, I wanted to kill.”

“It’s a moment-by-moment thing. Sometimes I feel very tranquil and other times I don’t feel tranquil at all. What’s going through my mind right now is to use the minutes and hours I have left as fruitfully as possible. It helps to live in the moment, in the essence that we use it productively. Right now I’m feeling calm, in large part because I’m here with you.”

Well That’s Interesting: Boats

Meanwhile, life continues to rule.

Opening Sentences

Openings in directly quoted dialogue:(*)

Openings in directly quoted dialogue:(*)

“‘Either foreswear fucking others or the affair is over.'” – Sabbath’s Theater, Philip Roth

“’49 Wyatt, 01549 Wyatt.” – In Parenthesis, David Jones

“‘Tell me things I won’t mind forgetting,’ she said.” – “In the Cemetery Where Al Jolson Is Buried,” Amy Hempel

Openings simply establishing who speaks and/or when and where we are in space and/or time:

“William Stoner entered the University of Missouri as a freshman in the year 1910, at the age of nineteen.” – Stoner, John Williams

“When I am run down and flocked around by the world, I go down to Farte Cove off the Yazoo River and take my beer to the end of the pier where the old liars are still snapping and wheezing at one another.” – “Water Liars,” Barry Hannah

“I am Gimpel the Fool.” – “Gimpel the Fool,” Isaac Bashevis Singer READ MORE >

An OuLiPian Pie

Yesterday, I baked this apple pie.

I love baking. It’s a completely different experience than cooking or anything else, really. I don’t know exactly what it is, but baking is relieving. Maybe it’s the quasi-precision baking necessitates.

See: when I cook, I don’t follow any recipe. Even if I’m cooking something for the first time, I modify the recipe as I go, adding this spice or that, more cook time or less, substituting ingredients whimsically, etc.

But with baking, there are basic rules I have to follow. For instance, the amount of rising element (eggs, baking soda, baking powder, etc.) and flour can’t really change. I certainly can’t arbitrarily decide the temperature of the oven or how long the thing bakes. I like this.

Writing Prompt: Ask a small person for assistance.

In 1966, Ornette Coleman did something odd. (Or, well, odder than usual for him.) He sat his ten year old son Denardo down at a drum kit in a recording studio and made a record with him called The Empty Foxhole.

Certainly this may not be the product of thinking something through completely. Having a shaky-timed ten-year-old play drums on your free jazz record plays into the “anyone can do that,” (see My Kid Could Paint That) critique leveled against Coleman’s pioneering musical career. And certainly, listening to the album reveals that the young man—now a respected pro—was, to be generous, a bit outmatched by his dad and Charlie Haden.

But what it may lack in musical virtuosity—a concept I will admit I am only passingly familiar with and devoted to, as I am more in the poorly record punk rock/noise/psychedelic/and black metal records camp—it sure does make up for with ENTHUSIASM! Enthusiasm is the wheelhouse of the ten year old. And the nine year old. And the eight year old. Etc. Working from a bed of this youthful enthusiasm, Coleman finds a way to weave some music I really like in and around the constraints of the young man’s limitations.

Here is a writing prompt. Ask a small person to tell you a story. Take notes. Tease out details when you think necessary. Encourage the small person to expand on promising ideas now and then. Mostly, though, just listen.

Treat the notes you have taken as a outline. Write a story or a poem. Whatever it is you write. Be faithful to your co-writer’s enthusiasm. But be your usual writerly virtuoso self within the outline’s constraints.

And credit your co-author.

Today in Class

Today class happened amidst the bumble and burst of plumbers and electricians, anxious dogs, and un-showered, tired, frenzied me. But it happened nonetheless. We workshopped a lot today. First, in whole-group fashion (there are 16 of us) to finish up where we left off last week with our reckless poetry. At the end of class, concentrating on sound and how sound moves through the air and into our ears and around in our noggins, students got into groups of three in which one person read while the other group members listened. After the poem, each group member wrote down what stuck the hardest in their memories, and then we talked about how the poems [we’ve been thinking about rhythm and chant] accomplished their sonic goals, or didn’t. That was fun. I bounced around the groups, interjected here and there, but mostly I let them do the talking. They’re all pretty smart readers, and I trust them.

Another of my favorite games is to annotate Philip Levine’s They Feed They Lion together with a class. I’m trying to teach students about writing annotation papers as writers versus as academic critics. It involves a helluva lot more looking at how craft informs our understanding of a poem versus simply what the poem means. Students get super frustrated, usually, about the phrase, “they feed they lion,” and they want me to tell them what it means. I tell them I don’t know what it means, but maybe by looking at how the poem is written we’ll start to get our heads around it. Chaos ensues. I write things on the chalk board. People start seeing biblical allusions and apocalypse. It’s great. Then I say something teacherly like, “well, how does all this anaphora and accreted repetition inform the poem?” Today I got some really astute answers that I’m too exhausted to expound on.

I showed students this excerpt from a Levine interview in which he explains the nascence of the poem [here] [I like the stories Mr. Levine tells]:

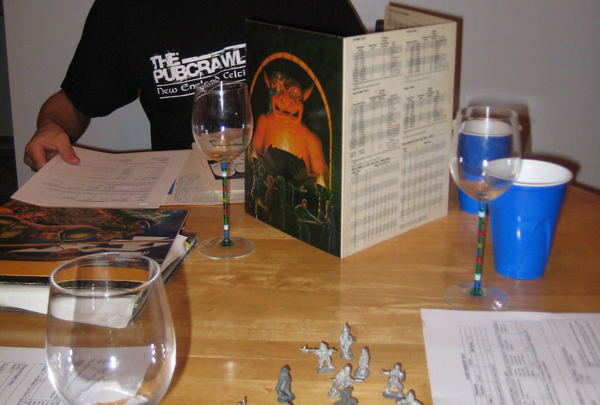

Lipsyte ate my brain and spit out a delicious chicken-fried steak

Sam Lipsyte has a really fantastic story in the new issue of The New Yorker called “The Dungeon Master.”

Next year, my collection of short stories, Happy Rock, will come out and it will include a story called “Rabbit Fur Coat.” It’s called “Rabbit Fur Coat” now. It was, in the first year and a half or two years of its existence, called “The Dungeon Master.”

Thematic similarities. Similarities in the characters ages. High school and role-playing games. Outsider freak and difficult friendships. Etc.

And so, the dilemma. Fellow writers (and people who like writing), what say you? Are you, in a similar situation, intimidated? Would you consider dropping the story from a collection? Or not sending said story out anymore, or for a while? Say, until the monster that is a badass story by a badass writer is no longer looming in your closet, making you feel inadequate to your writerly proclivities? Making you pull the sheets up over your head?

Say you’ve got some thunder you are are waiting to bring, and then a veritable god of thunder comes along and brings it first?

Should one cower? Or, hell, should one feel competitive? Should a writer buck up and maybe do a “Oh, yeah? That’s how you wanna play it, Lipsyte?” edit?

Ghost Writing

I’ve known a few writers who ghost write young adult novels for money which has always seemed both enticing and repulsive. On the one hand it seems like it could be really freeing and fun to work inside the constraints they give you (Nerd/vampire superhero lesbian coming of age story in post-apocalyptic Los Angeles– GO!) and under a pseudonym, but on the other hand I wonder if it would be too draining for how little money you might earn. Has anyone had any experience with it? Would you take a ghost writing job if someone offered it today? How much would you want to earn for it to be worth it?

Today in Class

I think I’m going to run a series called Today in Class every Wednesday after the workshop I’m teaching. This class is pretty much the highlight of my week, so I think it’ll be fun to share tidbits with a wider audience. I named the class A Deeper Poetics: The Art of Reading and Writing Poetry based on a Larry Levis quote, “What interests me here is a deeper poetics, one that tries to grasp what happens at the moment of writing.” What happens at that moment is weird and mostly indescribable, and likely different for everyone. Heather McHugh has written that a poet necessarily estranges language, that a poem’s motion, in some essential way, is an estranging motion. What happens when we put fingers to keyboard? Pen to page? Too much volition sometimes makes for boring work, not enough volition obscures resonance. Alexander Pope wrote in his poem, “Sound and Sense” that “sound must seem an echo to the sense.” Oh, but I don’t know. I don’t think that’s right. I think the sound (rhythm, chant) informs the subconscious, which in turns informs the poem’s sense. Ack! Today I made my students write an in-class response about this very topic. I gave them the above McHugh idea as well as another quote from her essay “Moving Means, Meaning Moves, “A poem is…a structure of internal resistances, and it’s no accident that paradoxes arise at the very premises of its act.” They also had some quotes from Robert Hass’s Listening and Making about the comforts of repetition and how the “completion of a pattern imitates the satisfaction of desire,” like an orgasm, according to Hass. I asked the students to use the quotes, and the essays, to frame a poem from this week’s packet, in which we looked at rhythm and chant.

We’re four weeks into the semester, and we’ve talked and written about brevity and image, place/landscape, and today we workshopped poems on the art of recklessness. Duh, I stole this week’s unit from Dean Young’s book title, and basically, I want students to feel really uncomfortable in making poems for a little while. Leave their comfort zone. Do some automatic writing. I want them to let the language, and also the rhythm, guide them line by line, word by word. We did an exquisite corpse of one word slant- and off- rhymes last week; everyone ended up with a folded up piece of paper with sixteen words on it. Their task was to write a 16 line poem, one word from the list per line. And they were great–despite the fact that the general sentiment (and the specific sentiment of one student) was that “this felt really alien.” One student wrote in a poem, “You, born an artichoke, green-gray scaley-spined and whorled. / Imagined being dinosaur. Returned to me a ghost.” Another wrote, “The mangroves warp / and root wrangle / sideways stacking strangleholds, / while marigold petticoats / and manifold destiny / sit in textbook centerfold: a centrifugal gamble.” I just happen to have those two in front of me (thank you Helena and Emily). They were all great explorations of how sound informs sense.

Today in class, too, we listened to Son House do “Death Letter Blues.” And to Langston Hughes read “The Weary Blues.” And I read WH Auden’s “Funeral Blues” : “He was North, my South, my East and West / My working week and Sunday rest.” God, I love that poem.