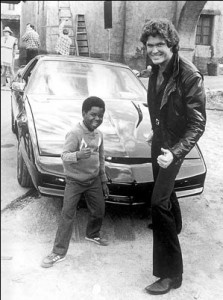

Gary Coleman teaches me something about writing.

A buddy of mine wrote to say that he had read somewhere that David Hasselhoff credits many of the choices he’s made in life, and much of his own ability to overcome the difficulties he’s face to his very close relationship with God. Included in the choices and overcoming is his decision to be on Knight Rider.

Some of my best friends are theists, so I’m not trying to bag on that sort of thing here. I will, however, suggest that maybe that voice talking to him and telling him to stick the TV show out for another season could’ve been KITT. Not all disembodied voices are the Lord. (“Remember when there was only one set of tire tracks? That’s when I was carrying you, Michael.”)

READ MORE >

Christine Schutt on the NYFA Chalkboard

What a happy thing to stumble upon! Christine Schutt–NOON editor, 2009 Pulitzer prize finalist, all-around badass–has written a short essay for the New York Foundation for the Arts website, about her work as a creative writing teacher at the Nightingale-Bamford school for girls. It’s a great piece about teaching, but there’s also a highly informative craft essay tucked inside it.

What a happy thing to stumble upon! Christine Schutt–NOON editor, 2009 Pulitzer prize finalist, all-around badass–has written a short essay for the New York Foundation for the Arts website, about her work as a creative writing teacher at the Nightingale-Bamford school for girls. It’s a great piece about teaching, but there’s also a highly informative craft essay tucked inside it.

I’m in complete agreement with Christine on this. I think reading one’s own work aloud is an essential part of the writing process. When something has been through enough drafts, I print it out and do an edit by ear, while listening to myself. The rule is: if I can’t say it in the world the way I’m hearing it said in my head, then it’s not done being written yet. And as a teaching tool, it’s incredibly useful for any kind of writing. Last semester, about mid-way through the course, I started encouraging my 101 students at Rutgers start reading their comp papers aloud to themselves, and the ones that did it improved measurably in areas like grammar, syntax, and overall coherence. What happened, I think, was that they heard with their ears what they couldn’t hear with their eyes. Once they saw the spread between what they thought they’d written and what they’d actually produced, they were in a position to start working on how to close the gap. Plus, that work to re-write sonorously forced them to do another whole revision. I think next semester everyone will be forced to do it from the get-go. But enough about me. Go read Christine’s essay.

The Spoiler

Recently, Alice Hoffman had a bit of a blow-up over a bad review that gave away too many plot points. (Also, the review was not altogether positive.) So, she argues something like this:

Recently, Alice Hoffman had a bit of a blow-up over a bad review that gave away too many plot points. (Also, the review was not altogether positive.) So, she argues something like this:

“Critics, don’t spoil my plots. I control the release of information, and am careful about how things unfold.”

After I read Never Let Me Go by Kazuo Ishiguro, I read some of the critical reviews and author spotlights that came out with the book and they almost all gave away a significant piece of information about it—a piece of information that Ishiguro does not himself mention (though it is hinted at, of course) until page 80. At an author event, I asked Ishiguro about it, and his shrugged it off. He didn’t care. He argued something like this:

“The ‘mystery’ in the plot is not important, but instead the mystery of the characters is. The book is not about the idea that drives the plot, but the way the characters live in the world I have created for them.”

Is someone right here? I really don’t know. Is Hoffman suggesting that the pleasure of reading her book is primarily in following the plot? And that if we know what happens, we’ll be disinclined to read it? If Ishiguro doesn’t care about what the critics revealed about his book, why did he wait for 80 pages to reveal it himself? The revelation was, in my reading experience, a very powerful one. Is he wrong to be fine with a critic depriving a reader of that powerful experience?

Are these two unrelated situations that I am throwing together?

The Greatest Adventure Story: Part Two, A Movie

He's so cute when he's angry

The other night, just after I read that Chabon essay about the Wilderness of Childhood, I watched This Is England on a whim and I was positively floored. It’s about a twelve year old boy in rural England in 1983 who becomes entangled with a twenty-something skinhead, who exposes the boy to a lot of violence and extremism. (The two main characters mirror each other perfectly: a child who is forced to act like a man and a man who can’t help but act like a child.)

The first thing that stood out to me was how beautifully it was plotted. Maybe I just picked up on this because my boyfriend has been reading John Gardner’s The Art of Fiction to me in any spare moment he finds, but we both couldn’t help but gush about how each scene was perfectly weighted to balance each plot line: the political context, racial tension, the boy’s romantic interest, the two main character’s back-stories and ideas about family and fatherhood.

Also, it’s acted beautifully, written beautifully and is somehow extremely funny, horrifying, engrossing, violent, and heartbreaking all at once. It’s the kind of movie that I feel is an education in plot and character development. It’s up on Netflix and you can stream it right now if you’re so inclined. I already want to watch it again.

What are some other movies that you feel have been beneficial/influential to your writing?

Demon Brother: 6 Thoughts on Heart in Fiction

I’ve heard / been asked a lot about the concept of ‘heart’ lately, and last night I couldn’t sleep. So here:

1. Writing your heart out to me does not express heart. What expresses heart is the well wrought idea, sentence, conception. I, a reader, care because you care, and how the saying is said shows. If you could not take the time to say something to me in a way I might remember, I will not remember. Misconstruing a subject matter as ‘human’ only goes so far, which is, often, not far at all. I can always go outside.

2. The reader can always go outside. The question is not ‘Why are you telling me this?’ but ‘In what way are you saying this that would make me extricate this now from anything anyone before or after you has ever said?’