Sunday Service: Joe Aguilar Poems

The Tiny Crown of Life

I lay in bed without makeup.

I lay my cheek on bible leather.

TV shows are waking life.

Commercials are dreams.

I steal Mom’s necklace.

We trip on down the road.

Hands on Dad.

I suffer the tiny crown of life.

I suffer my ponytail.

A locket keeps a small gas star.

Light moves all over my Jordans.

By the sea we all hug.

By the sea a hand sifts through mine.

Jellyfish boil in the spume.

My hair whips out.

We saw away my ponytail.

Captivity #1

How our temple brightens these young hills. We of Saxon strain. We of the Lord. We learn of heathens only when gunfire clatters the house. Out our window homes are burning in the snow. Our neighbor runs into the woods grabbing his organs in. The snow is loud with fire. They are so many strong even our dogs do not rise up. Still I wait on the Lord’s will in the kitchen with my child and my knife. Still the heathens shoot through the glass through my arm. I get dark with hate and pain. They come to us. They walk us gory through the rocks and ice. They walk most of us dead. They leave us in drifts where we drop. Still the angels feel thick around us in the half-light. My child fouls herself astride the pinto. She growls at me. The smell of us. Still I trust the Lord might set His hand to heal my wound. What they call their village but a strew of twigs. What they call their homes but errata. The swollen hole in me that leaches white. They guard us in a muddy hut. Still our nights and days full of the peace of the Lord. Overnight my child expires in the filth without a noise. Still the Lord says not to weep but keep an eye to His relief. Still the Lord says justice is mine. The pale horse. They wrap my bluing arm in oaken leaves. They grouse around their fire. They smoke a weed. I watch the hills for English steeds. I want their heads to break. I want the snow to dark. I want the Lord.

Joe Aguilar lives in Missouri. His work is in Puerto del Sol, LIT, Caketrain and elsewhere.

Sunday Service: Molly Brodak Poem

Hex

Gorges ago

in gymnasium-Church

under puff

of sleeve

in acid orange/

lavender/brown

& weak yellow

I felt punched

& sensed a new hollow

where a verse wormed:

He will spit you out

& the candy-bunny hollow

now punched

with He will spit you out

held hollows upon

hollows, cellless organs

& blank synapse billows

of He is not coming here

I am spit out after gorges of

gorges of minutes having

soft-snapped my tooth off

& held it all service

all heartless singing

all heartless repeating

held it under my tongue

finally spit from His mouth

the glassy hollow charm

& now feeling handless

& calm in gymnasium-Church

that one time only.

Molly Brodak is the author of A Little Middle of the Night (U of Iowa Press, 2010) and is the 2011-2013 Poetry Fellow at Emory University.

September 11, 2011

In 1953, Rene Magritte painted a large group of intricately organized near-identical men suspended in the air, their somewhat weary context solely established next to a building, named “Golconda” after the ruined Indian capital of the ancient Kingdom of Golkonda (c. 1364–1512). The city was built by a Hindu king, and later conquered by an Islamic kingdom. Religion is the impossible imperative of possibility. When Donald Rumsfeld said “the absence of evidence is not the evidence of absence,” he was referring to absent weapons of mass destruction, though I consider such invocation an invitation to God, or at least the idea. Buddhism’s genocide smear record is less red than Islam and Christianity, but it’s so very easy to close your eyes and meditate and to want nothing. Buy a bath robe at Target and you’re almost home. “I don’t know if God exists, but it would be better for his reputation if he didn’t,” goes Jules Renard, and I imagine Oscar Wilde or Woody Allen moving such lips. The eloquent writer, myself included on a good day, may well be an asshole. In 2001, exactly 10 years ago this restful Sunday, an unknown man, among many other fallen (literally) ones, was captured by someone’s camera lens in his growth towards his concrete demise, a descent man no doubt. The image is more striking than others: the passive restraint of his limbs; the vertical backdrop cast by the edifice from which he had recently departed; the stately gravity of a non-angel. He does not flail nor mime an impossible flight with the skeletal wings of a human arm. Tilt the image 90° clock-wise and he seems to be resting comfortably on a mattress, some mild nightmare about being forced to jump out of his office window the next hypothetical morning, a Tuesday ’twas. Surrealism purports non-rational significance, meaning a bunch of people can’t just hang out gracefully in the air. They must, as grand spiritual vectors, ascend or descend. Falling is not falling, but a small object’s migration towards a larger object. Newton killed God, Einstein killed Newton, and Nietzsche tried to catch up. An object falling freely towards the earth’s surface increases in velocity by 9.81 m/s (22 mph) for each second of its descent. In a vacuum, of course. Ignoring air resistance, those subtle wisps of buoyancy felt in one’s shirt, as hands of angels or ghosts.

Metal Easter

As it’s my tradition at Halloween to listen to a Christian heavy metal song called “All Hallow’s Eve,” so it is at Easter that I commemorate the good news with this, from Barnabas:

The music is bad but at least the lyrics are an abomination:

I killed Jesus Christ

Yes I did it’s true

Oh I killed Jesus Christ

And you were with me too

My personal liturgy isn’t meant to be sacrilegious, though. For me its nostalgic; I really loved that song when I was 14, and anyway I think the Gospel, offensive in any time signature, is truly an amazing story. For God, having decided not to flood the world again, needs to save creation from our own evil — our sin this time not hating the truth but systematizing it — so he makes the smallest action possible. He becomes one of us, one whom we — recognizing his power for an actual justice — need to kill. In that death some of us would see horror and in that horror be baptized.

I don’t think my summary captures the story nearly as well as Cool Hand Luke (and if you want further evidence of our need for grace, just read the comments to this trailer).

My Halloween Tradition

is to listen to this song, every year since 1993.

This is from Bride’s third album. They are a Christian band from Kentucky.

Lynne Tillman Story

[The following is a story originally published in Bald Ego magazine, and will appear in Lynne Tillman’s forthcoming new story collection from Cursor in April 2011, titled Someday This Will Be Funny. The piece’s title comes from Clarence Thomas’s words in his testimony during the hearings, October 1991. Recently, Mr. Thomas’s wife allegedly left Anita Hill a voicemail asking for her apology. The story makes interesting use of popular media snafu as subject matter, which made me wonder more about what other great books and stories are able to incorporate such into their bodies in a fictional sense fluidly. Thoughts? – ed.]

Give Us Some Dirt

On long, summer nights in Pin Point, the Georgia air hung still as a corpse, and they’d wait for a breeze to save them. The heat felt like another skin on Clarence. His Mother would say, Clarence, what have you been up to? Playing by the river again? Oh Lord, we’ve got to clean you up for church, but aren’t you something to behold? And his mother would clap her palms together or spread her arms wide, like their preacher. Oh, Lord, she’d exclaim. Sometimes she’d point to sister and lovingly scold, “She doesn’t get up to trouble like you, son.” Clarence scrubbed the mud off until his knuckles nearly bled, while his sister giggled.

These days she wasn’t laughing so much.

The dirt couldn’t be washed away, not after Clarence kneeled in their white church, and they slimed him with derision. They couldn’t see who he was, how hard he’d worked, what he’d had to do, but he knew how to act. Behave yourself, boy, Daddy would say. Clarence’s grandfather, Clarence called him Daddy, was a strict, righteous man, who never complained, not even during segregation times, didn’t say a word, so Clarence wouldn’t, either. Those days were over, and they had their freedom now. He set Daddy’s bust on a shelf near his desk in his new office.

The D.C. nights mortified him, the air as suffocating as Pin Point’s. Clarence couldn’t free himself of history’s stench. On some interminable evenings, he nearly sent that woman a message, made the call, because she’d dragged him down for their delectation. He would pick up the receiver and put it down.

The noise of the ceiling fan assaulted him like a swarm of bugs. Clarence’s jaw locked, and his strong hands balled into fists. Every pornographic day of his trial, Clarence’s wife, Virginia, sat quietly behind him. She barely moved for hours on end, didn’t betray anything, and he worried that, if she had, the calumnies would have spread even further. The sniggers and whispers would have ripped her and him to pieces. He rubbed his face, recalling her startling composure. Rigid, at attention, a soldier in his beleaguered army.

He didn’t tell Virginia what the senators whispered — if he’d tried to marry her, if they’d had sex before the Court decided Loving v. Virginia, they’d have been arrested, and wasn’t it ironic — the Court made Clarence’s dick legal in Virginia, in Virginia? The Capitol’s dirty joke. Their dry Yankee lips cracked into bloodless grins.

The room’s high ceilings dwarfed him. Clarence glanced at a stack of legal papers. His wife was unassailable and white, but under their vicious spotlight her skin looked pasty and sick. She clung to him through his humiliation, even when disgrace lingered like the smell of shit. And now she bore the tainted mark with him.

Clarence wouldn’t say anything. He’d absorbed Daddy’s lessons, he could keep everything inside, all of it. He watched his grandfather’s bust, half expecting it to move, but it only stared down at him from the shelf. Clarence picked the receiver up again and put it down again. He was in that weird trance, and breathed in slowly, to calm himself, and breathed out slowly, to stay calm, and then closed his eyes. Clarence would leave that woman alone, leave her be, and, anyway, what was the sense, what was there to say years later, and there’d be consequences.

He was weary of scrubbing.

When he won, when the seat was his, he watched his friends’ joy, black and white, and they embraced him, slapped him on the back — remember what’s important, what it’s for, our principles, it’s all worth it. Clarence was the blackest supreme court justice in the land, the blackest this country would ever see. He knew that and held that inside him, too. Nothing and no one could whitewash that.

Clarence patted his round belly. He liked to joke about his heft, his gravitas, with his friends and the other Justices. When he delivered his rare speeches, he occasionally mentioned his girth, which drew a laugh, since his body was a source of mirth. Sometimes his hands rested on his stomach during sessions, when he was courtly if mute. The court watchers noted that he never asked questions, they remarked on it until they finally stopped. Clarence felt he didn’t have to say a word. He’d talk if he wanted, and he preferred not to.

When his hair turned white, like Clinton’s, that other fallen brother, Virginia said he looked distinguished, not old. Still, she worried about his weight, she didn’t want to lose him. He hushed her. He intended to be on the bench as long as he could, at least as long as Thurgood Marshall. He looked at Daddy again, eternally silenced, and sometimes talked to him, telling him almost everything. Clarence could hear Daddy, he could hear his voice always. He knew what he’d say.

Clarence’s trial bulged fat inside him. He’d never forget his ordeal, not a moment of it. He closed his briefcase and felt the urge to push Daddy from his perch. He would never let anyone forget his trial. Clarence chuckled suddenly, and a harsh, guttural noise escaped from him like a runaway slave. He’d have the last laugh, he was color blind, and they’d all pay in the end.

Lynne Tillman has published novels, story collections, and works of nonfiction. Her novel No Lease on Life was a New York Times Notable Book and a finalist for the National Book Critics Circle Award, and she received a Guggenheim Fellowship in 2006. Her most recent novel is American Genius: A Comedy.

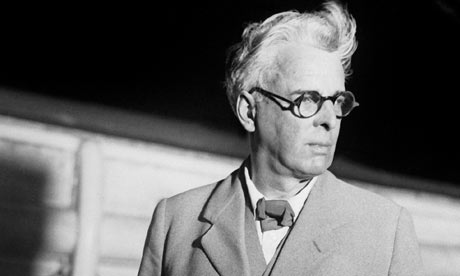

Yeats + Some n+(x) Iterations of Yeats

Apprentice Oulipian

A Coat

I made my song a coat

Covered with embroideries

Out of old mythologies

From heel to throat;

But the fools caught it,

Wore it in the world’s eye

As though they’d wrought it.

Song, let them take it

For there’s more enterprise

In walking naked.

A Coating

I made my songbird a coating

Covered with embryos

Out of old nags

From heifer to thrombosis;

But the feet caught it,

Wore it in the world’s eyeball

As though they’d wrought it.

Songbird, let them take it

For there’s more entertainment

In walkout napalm.

Melissa Broder Poem

Supper

Everyboy comes to me at a church potluck

perfumed with frankincense and lasagna.

He believes I am a gentle bird girl

in my tulip sweater and raincoat.

I am not so gentle, but I act as if

and what I act as if I might become.

He says: Let’s be still and know refreshments.

Tater tot casserole is wholesome fare.

Let’s get soft, let’s get really, really soft.

I do not say: I am frightened of growing plump;

something about the eye of a needle

and sidling right up close to godliness.

Instead I dig in,

stuff myself on homemade rolls,

tamale pie and creamed chipped beef with noodles.

I eat until my bird bones evanesce.

I eat until I bust from my garments.

I become the burping circus lady

with meaty ham hocks and a sow’s neck.

Everyboy says: Let’s get soft, even softer.

We vibrate at the frequency of angel cake.

Our throats fill with ice cream glossolalia.

The eye of the needle grows wider.

There is room at the organ bench.

I play.

Melissa Broder is the author of the poetry collection WHEN YOU SAY ONE THING BUT MEAN YOUR MOTHER (Ampersand Books).

Tim Jones-Yelvington Short

Clean Babies

While we fucked, I’d hold his baby. To keep the baby off the dirt. Clean babies are happy. I’d hold the baby out in front, and he’d fuck me from behind. The baby never cried. The baby wandered. I mean its eyes. The baby appeared unfazed. I mean by the fucking.

We fucked in the park, in the tall grass. When my arms that held the baby bounced, the baby laughed and laughed. And while I got fucked, while I was holding the baby, I’d wonder about the baby’s other daddy. This was what I assumed, that the baby had another daddy, because unlike his first daddy, the daddy who fucked me, this baby was brown. I figured the baby was adopted. Something about the daddy, I could just tell, he seemed like the kind of man with a man at home. Even though he never talked about himself, he didn’t seem like he kept any secrets.

I wanted to ask him, Bring the other daddy to the park! One daddy to kneel on the ground and take me in his mouth. The other daddy to fuck me. And me to hold the baby. To keep the baby clean. But I never had the guts to ask.

That was a few years ago. That daddy disappeared. Now that park has fewer babies. Now those babies toddle. Oh man, those babies are getting big.

Tim Jones-Yelvington lives and writes in Chicago. His work has appeared or is forthcoming in Another Chicago Magazine, Sleepingfish, Annalemma and others. His short fiction chapbook, “Evan’s House and the Other Boys who Live There,” is forthcoming in Spring 2011 in “They Could no Longer Contain Themselves,” a multi-author volume from Rose Metal Press. He is editing the October issue of Pank Magazine to feature Queer poetry and prose. He contributes to the group blog Big Other.

Terese Svoboda Excerpt

Excerpt from Pirate Talk or Mermalade, a novel in voices to be published this fall by Dzanc Press.

1718 – Nantucket Beach

1

I’ve seen boats as big as this whale. I’ve seen gryphons the same size, with teeth growing in even as they were taking their last breath.

You have not. And not a live one.

I’ve been to sea, I’ve seen all you’re supposed to, being at sea. I am sixteen, after all.

If you’d stayed at home, you would’ve seen to Ma. I’d be a pirate twice, with two voyages under me, if I didn’t have that.

Quit your carping. Go stand on its middle. Maybe it will release its wind if you jump on it.

For sure it will stink to heaven if I jump on it.

Let’s poke out its eye.

It’s a wonder you’re not tired of poking whales, a-roving on the ocean like you do, with all the new sail.

Here’s the stick–let’s do the eye.

Cap’n Peters says there’s luck in a whale’s eye. And money. Some men use saws on such as the eye, to examine the socket and take away the skull too.

You told this Cap’n Peters about this whale?

Cap’n Peters can see it himself. He’s anchored out beyond the neck, nearly done scouring the fresh-wrecked Abingdon. He’ll come.

Our greasy luck! Then the sooner it dies the better, and not for anyone else but us to collect it.

It’s alive all right. Look at the eye.

Help me with the stick. A donkey could haul it out, where could we get a donkey?

If we had a donkey I wouldn’t be walking the beach looking for rope to catch the mussels on, would I? If we had a donkey, you wouldn’t be shipping out every time the wind blew and leaving me here with Ma, myself only in short pants still and no cutlass.

We need a donkey. The smell alone will bring Peters.

Do you believe in whales? I mean, that they talk?

Two fiddles can talk. One calls, the other says Yes and then some.

Whales dance when there’s boats coming with harpoon.

The way pirates do on the gallows.

Not all of them.

They’re crying whales, not singing. Poke here.

They swallow the pennywhistle and dance on the tips of their tails on top of the water. And sing.

Whales cry about their future like all creatures worth killing. There’s a tear now, with Peters coming. Look–I can make it dance without singing.

Let it be, it’s starting to bleed.

I’ll let it be with a cut of the knife. If only I had a good one, if only Ma hadn’t sold that bit of a blade while I was gone.

She’s sold all her brooches, down to the tin-and-garnets.

She sold the true baubles after you were born—or gave them up, cleaned out by whoever she had after you had a father, cleaned out clean as a pike in a trough.

They use beetles to clean the skulls when they’re empty. Cap’n Peters says so.

Peters, Cap’n Peters–would he be the one seeing Ma now?

He’s seen all of her, if that’s your actual meaning. How huge those skull-cleaning beetles must be, so big they can’t walk after all that eating, beetles that could eat all of every one of the colonies.

Slippery here, whoa.

Cap’n Peters’ has got his glass on us now. There, over the wave.

No.

Tease me like you don’t know he’s watching. Play foot-in-the-water. He’ll think we are but boys and won’t beat us then when he sees us.

We are but boys. If I only had a knife—

If you grouse and slaughter the whale before him and he balks and whines, Ma will tie herself to the rafters and I will have to cut her down. It’s a poor revenge for her living from one man to the next, though she swears Cap’n Peters is her utter last.

I told you to get her set right, to take Ma to someone while I was off at sea, a woman with a cure.

She wouldn’t go, she said she’d have no business with someone like that, she didn’t need no one other than Father. She talks to Father from the rafters where you can see the sea out the little window, she talks to you out that window too.

She doesn’t know who Father is.

This be true, but still she talks.

This fish is leaking like a ship come ashore.

Whale, it’s a whale, not a fish. And if you would quit your poking at the eye, it wouldn’t leak so much. Poking it like that makes the sound it makes worse.

You talk like a sea captain with your Don’t this and Fish that, a bloody captain, the kind I don’t take to.

It’s the life of the sea, you said. Yo, ho, ho, you said. You toe the line, you said.

I will give you another punch to match the first.

It breathes–hear it? Cap’n Peters says they are cousin to us.

I can’t hear anything while you blather on about Cap’n Peters.

I say we leave it alone because Cap’n Peters will pay us to chop it up. They’re bound to want the steaks and oil even if it be old, and some of the bone to hang hats on,

and bone for those who truss up the women.

That’s real work, all that chopping.

Aye.

The bone is all I want–I can carve “The Apostle on the Desert” into the bone.

I can carve that–one cut meeting another.

You are a stupid boy. Look–it thinks it is a creature of the land now, it wriggles so, it wants to walk about on its tail. With the next big wave, let’s push it in with our backs.

Let’s kill it.

Die, die.

What’re you whispering?

Nothing. Die, die, or they’ll get you, you whale of us all, you fool whale.

You are whispering.

I’ll whisper if I want to.

The whale’s dead anyway. Why else is it up on the beach?

Not breathing like this it isn’t dead. Not yet.

Look, Peters is bringing hooks and axes. And a cutlass! There’s a knife.

It’s so soapy-feeling on the outside.

Pitchforks and pries. Let’s poke it through to the brain before they get here, let’s poke it to make it dead before they poke it, so we can claim it and get the bone. I am grown, after all.

Die, die.

Why do you cry like a girl?

I’m not a girl.

Whale-lover, then. Crybaby.

Listen to it breathe.

I can’t hear anything but Cap’n Peters and his men beaching loud like six blacks banging dishpans.

It’s breathing big.

There–I’ve got the stick through, no thanks to you.

It still breathes.

If I hang on it here and pull down, the whole side will rip and they’ll know it’s ours. Give me a hand–

Pirate Talk or Mermalade is Terese Svoboda’s fifth novel. Publisher’s Weekly called it a “jeu d’esprit of the privateer life.” It comes out on “Talk Like a Pirate Day.”