Craft Notes

FRESH OFF THE NEUE GALERIE: “THE ATTACK ON MODERN ART IN NAZI GERMANY, 1937”

Last Saturday I went all the way uptown to Neue Galerie to see the first American exhibition on the topic of “Degenerate Art,” which will be available through June 30, 2014. One of my favorite subjects during my ultra-brief academic career (aka “undergrad”) was the exploration of the factors that made the transition from the Weimar Republic to the Third Reich possible. Above all other realms, that of culture was the one that appealed to me the most in my studying of how the German people were capable of gradually dehumanizing “non-Germans,” and to what extent this process was a political construct smoothly created by the Nazis. Reactively responding to German people’s despair and economic insecurity, Nazis built an ideology that made it possible for Germans to replace fear with hate for anything different. I am still fascinated by the institutional curating of art performed by the government, and what it translated to in political terms to have government authorities declare the validity of certain art, while condemning the existence of other art.

Maybe you should go see it if you feel like it and happen to be in New York, even if the security staff is unnecessarily rude. Especially if you are not familiar with what was presented as “Degenerate Art” and how it became a key tool in spreading Nazi propaganda.

My favorite thing about the Neue Galerie exhibit was the curatorial decision to dedicate the lower level part of the exhibition to a mourning ritual. Specifically, the curatorial team conveyed a sense of cultural loss by presenting empty frames in the place of artwork that was intentionally destroyed by Joseph Goebbels’ Commission for Disposal of Products of Degenerate Art, the government body responsible to preserve the German identity. An inventory which chronicles the status of what was labeled “Degenerate” can be also found downstairs, listing more than 16,000 artworks the Goebbel Commission would destroy, exchange or sell.

Below is a briefish description of what comprised “Degenerate Art.” Through the government’s calculated juxtaposition of “Degenerate Art” to what was presented as “German Art,” the beginning of an idealized Nazi identity was rapidly spread, effectively brainwashing people into seeing “different” as “wrong” and “dangerous.”

ENTARTETE KUNST (DEGENERATE ART)

The Entartete Kunst exhibit opened in Munich on July 19th 1937, and was one of the most visited shows by German citizens. It focused on works that belonged to the Expressionist movement, being created chronologically between the end of WWI and the first years of the Weimar Republic. The populist propaganda of Adolf Hitler placed him in the position to evaluate what was meaningful and good in art: conventional realism and work resembling ancient Greek statues. Any work that did not abide to his stylistic vision–Expressionist, Cubist and Dadaist work–was labeled as unhealthy and dangerous. Entartete Kunst’s ultimate goal was to cease the production of such work: a celebratory funeral for Expressionist art.

Doomed as unrealistic and violently emotional, this artwork was publicly displayed as “the work of degenerate minds,” the exhibited work served as a sensational depiction of the sick minds of “those who could not handle reality.” The themes that functioned as excuses for the Nazis to group work as “entartet” were naturally aligned to their Race ideology: Jews, Bolsheviks, un-Christian, Socialists were all protagonists.

The curatorial organization provided ample ridicule and mocking of the artists as the commentary that accompanied their work in lieu of a regular description. To further deteriorate and diminish the significance of this art, the work was presented as a mass, piled to transcend its insignificance: it was not worth more space. The eerie and uncanny element that defines this art menaced the facade of harmonic balance the German people were accustomed to viewing as their ideal world. Any social or economic difficulties and problems the state was facing were directly linked to the aforementioned “others.” This dehumanization was a necessary part of the Nazi plan for what was to follow.

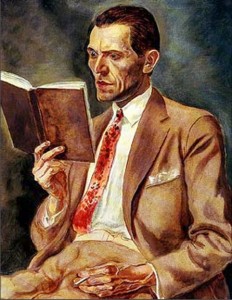

Oskar Kokoschka, George Grosz, Paul Klee, Ernst Ludwig Kirchner, Fritz Bleyl, Erich Heckel and Karl Schmidt-Rottluff were some of the most heavily criticized artists. The Nazi community perceived their work as the result of a sick and distorted youth. Their staggering creative individuality was portrayed as a threat to the nation: these people were different from the Germans, thus posed a threat to the collective pursuit of a uniform Aryan identity. Most expressionists felt no inclination to belong to Hitler’s Volk, but rather felt like setting themselves apart as individual entities rather than a part of the mass.. Most of them had recently returned from the war and used art as a means to cope with their experiences, guilt and post-traumatic stress disorder. Many of these artists used drugs–particularly sleeping pills, morphine and alcohol–to self-medicate, another quality the Nazis used to otherize them as dysfunctional and code them as the source of the problem.

DEUTSCHE KUNST

Simultaneous to the persistent effort to humiliate Expressionism, Hitler and Joseph Goebbels wanted to provide an exemplary approach to art: a unifying, simple and realistic“German” art. Hitler’s artistic aspiration as well as his utter lack of a creative spine are widely known. The emphasis of the mode of art that they wanted to promote was one devoid of the complexities of human nature. Nationalist themes were prominent in this exhibit, which was naturally curated in an elegant and spacious manner; every piece given adequate space to provoke the appropriate response of respect and admiration from the audience.

Restricted to the clean replication of visual imagery, this sort of art is constrained to evoke nothing more than beautiful landscape or the beauty of Apollonian bodies reminiscent of Greek Kuri and Muses or a strongly homoerotic superhuman figure. While all of these subject areas are visually pleasing, they give no space to create work that is visceral, that is political, that instigates a strong reaction or dialectic. Even when the subjects were nude they lacked any sexual element, emanating a discomforting vibe of a pedophilic nature or an undeveloped sexual maturity. One of Hitler’s favorite artists was Adolf Ziegler, whose painting Weiblicher Akt (1942) depicts a young woman who is a clear example of this sexual nonchalance. Adolf Ziegler’s statues–largely influenced by the work of Michelangelo and Auguste Rodin–are illustrative of the superhuman figure the German man was to try to emulate: the intended aspiration, the everyday hero.

(NOTE: Big Chunk of this comes from a vintage essay I plagiarized, which you can find here )

Tags: art, degenerate art, die Bruecke, entartete Kunst, Ernst Ludwig Kirchner, Max Beckmann, Nazi, Neue Galerie, Oskar Kokoschka, paul klee, Third Reich, Weimar Republic

wow, hard to believe it’s the first exhibit. maybe the first to explicitly center on that topic? anyway, good write up.

yes, that s what i meant. sorry it was unclear. but crazy regardless, i think