Craft Notes

meta-blah

I’m reading Clarice Lispector’s The Hour of the Star. Lispector is a powerhouse writer, no question about it. Her sentences are like the rapture, like the world is ending all around me and there’s only this, her words, and I want to grab them by the fistful and hide them in my shirt pocket for safekeeping, even though doom and thunderbolts are all around me. BUT, but, even as I read, I’m skeptical because the book is metafiction, and I’ve found myself increasingly bored with metafiction.

So let me back up a bit: I remember the first meta books I read, Gass’s Willie Master’s Lonesome Wife and Federman’s Double or Nothing. I came to metafiction late, the summer before grad school. I remember the epiphany, like wow, I didn’t even know fiction could do things like that. I mean, I’d read books with meta elements in it before, for instance, a lot of Calvino and Carson, but there was something about Gass and Federman that really drove it home for me.

Flash forward a year and a half later. I’m still in grad school, but I’ve read a lot more. I’m on a train, from South Bend to Chicago, to get on a plane to go to Texas, I think, if memory serves me, and I’m reading Salvador Plascencia’s People of Paper, and I’m loving it, like loving it more than many other books I’d read. The story is smart, the form is exciting, etc. etc., and then, bam! It turns metafictional. The moment Saturn is revealed to be Salvador Plascencia, I lost interest. One trick pony kind of thing, only the pony is missing a leg, which isn’t clever or unique but malformed and a bit pathetic. I finished the book, unimpressed with the way the narrative turned.

Last fall, I taught PoP to my Advanced Fiction Writing class. Most of the class suffered through the first third of the book. They had a hard time understanding how the narratives fit together. They couldn’t make the connections, BUT THEN, the second section, Saturn is given an identity and the book turns meta, and the students LOVED it. This made the book work for them. They had the same reaction I had to meta when I first came across it. They rejoiced, many of them chanting: I didn’t know fiction could do that. And yet, this was the precise moment when I grew bored. And second, third time around, I was even more bored with the trick.

And it continues, the boredom. Even as I read Lispector or Sorrentino (who I love), I’m weary of it. I want something new. So I wonder about the form. I’ve read meta recently that works and works well, but there’s something about the mournful writer writing about writing, ugh, just so exhausting. I appreciate meta when it’s smart self-consciousness, but it seems like a lot of meta stuff I’ve read lately is plain boring.

Earlier today, I had a conversation with Matt Bell about metafiction. Here’s part of it, many of these statements were “probed”:

I think there’s a lot of tired ass metafiction out there, but that’s a limit of imagination, not of form. I remember reading Egger’s HBWOSG, which is probably a book I’d struggle to get through now, but ten years ago, when he’d break the story to acknowledge the fact that he was fabricating the scene you were reading, and then the characters in the scene are discussing that, etc., I was kind of blown away. Like, OH NOW EVERYTHING IS POSSIBLE, which is such an ignorant reaction—I just hadn’t read anything yet.

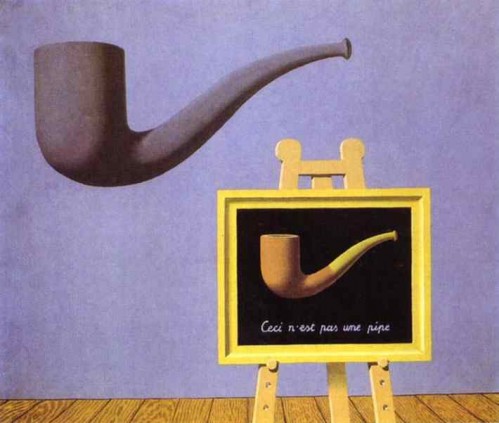

Or think about this: the OED says metafiction is: Fiction in which the author self-consciously alludes to the artificiality or literariness of a work by parodying or departing from novelistic conventions (esp. naturalism) and narrative techniques; a fictional work in this genre or style.

Given this definition, how can metafiction be boring? How can it be tired? And yet, it’s both these things. It’s been done very well, by many people, and now, what’s left? But here’s my problem: I write metafiction. Almost all my books have some metafictional element, so selfishly, I want to know which aspects of metafiction are worthwhile, which need abandoning, because despite the overall tenor of this post, I don’t think metafiction is dead. Prove me right, metafiction, prove me right.

Something a professor told me in undergrad that solves a lot of problems in life, as a writer:

If you need the trick, you can’t have it.

If the story is compelling without the arched eyebrow, if the language is good and if the characters would be exciting even if they weren’t constantly nudging you with their elbows, then you can go meta and maybe there’s some extra juice in that. But usually if you need it, you probably can’t have it. Hard lesson for me to learn. Still learning it. Probably not always true. But a good place to start.

Something a professor told me in undergrad that solves a lot of problems in life, as a writer:

If you need the trick, you can’t have it.

If the story is compelling without the arched eyebrow, if the language is good and if the characters would be exciting even if they weren’t constantly nudging you with their elbows, then you can go meta and maybe there’s some extra juice in that. But usually if you need it, you probably can’t have it. Hard lesson for me to learn. Still learning it. Probably not always true. But a good place to start.

I like that a lot. Who was the professor?

I like that a lot. Who was the professor?

Dan Barden. Dude knows his stuff. I am struggling to remember this with my book right now, which is about bombs that look like people. I have to constantly remind myself they have to work without the bomb thing.

Dan Barden. Dude knows his stuff. I am struggling to remember this with my book right now, which is about bombs that look like people. I have to constantly remind myself they have to work without the bomb thing.

lispector is saying a lot about gender in her choice of having a male author “create” Macabea…it doesn’t come thorugh allegedly as much in the english translation. Hour of the Star is one of my absolute favorites. And I think with that book especially you need to have an author-narrator because Macabea as a character is so unformed, hasn’t come yet to consciousness, so the narrator watches and remarks on her journey.

lispector is saying a lot about gender in her choice of having a male author “create” Macabea…it doesn’t come thorugh allegedly as much in the english translation. Hour of the Star is one of my absolute favorites. And I think with that book especially you need to have an author-narrator because Macabea as a character is so unformed, hasn’t come yet to consciousness, so the narrator watches and remarks on her journey.

Lily, you mention having read and enjoyed Calvino– at the moment I’m reading “If on a winter’s night a traveler.” For me, what makes the book hold together (other than Calvino’s charm and willingness to be playful on every level, meta- and not) is that it uses its meta-ness to create a meaningful mythology about what it means to be a reader, to be reading. He portrays the act of reading, something readers are familiar with, in a way that honors its everday magic, that reminds us that it’s something more than what we’re used to thinking it is.

Without the meta, he wouldn’t be able to give you the same effect. The meta, in this case (for me anyway!) enlarges the experience. It recreates the experience.

(Is this the key to successful meta? To use it to create a meaningful mythology about something we’re probably already somewhat familiar with? To defamiliarize? And for it to not be the END, but the MEANS?)

And to respectfully disagree with Mike, in the case of this successful example (Calvino), anyhow, the meta does more than give a little extra juice. The meta plays a significant role in making this book (for me) super-great. Without the meta, the book might work, but it would work in a very different way, and be about something else.

(That said, Mike, I in general agree with the do-you-need-the-trick principle, in the sense that it can help a writer avoid the temptation of using meta to unsuccessfully TRICK OUT or PIMP UP an anemic story.)

Lily, you mention having read and enjoyed Calvino– at the moment I’m reading “If on a winter’s night a traveler.” For me, what makes the book hold together (other than Calvino’s charm and willingness to be playful on every level, meta- and not) is that it uses its meta-ness to create a meaningful mythology about what it means to be a reader, to be reading. He portrays the act of reading, something readers are familiar with, in a way that honors its everday magic, that reminds us that it’s something more than what we’re used to thinking it is.

Without the meta, he wouldn’t be able to give you the same effect. The meta, in this case (for me anyway!) enlarges the experience. It recreates the experience.

(Is this the key to successful meta? To use it to create a meaningful mythology about something we’re probably already somewhat familiar with? To defamiliarize? And for it to not be the END, but the MEANS?)

And to respectfully disagree with Mike, in the case of this successful example (Calvino), anyhow, the meta does more than give a little extra juice. The meta plays a significant role in making this book (for me) super-great. Without the meta, the book might work, but it would work in a very different way, and be about something else.

(That said, Mike, I in general agree with the do-you-need-the-trick principle, in the sense that it can help a writer avoid the temptation of using meta to unsuccessfully TRICK OUT or PIMP UP an anemic story.)

Kate, I agree that interference is necessary, and I ought to also say I love this book too, but, BUT the metafiction is still problematic to me. What I love, however, is, as you say, the gendered politics of Lispector picking a male narrator-author as a vehicle to create un-created, un-formed, malformed Macabea. This says a lot, and I’d much rather hear the narrator-author wax poetic about Macabea (which is what I appreciate, deeply, about this book), rather than another “tired” soliloquy about how hard it is to write a book, character, etc.

Kate, I agree that interference is necessary, and I ought to also say I love this book too, but, BUT the metafiction is still problematic to me. What I love, however, is, as you say, the gendered politics of Lispector picking a male narrator-author as a vehicle to create un-created, un-formed, malformed Macabea. This says a lot, and I’d much rather hear the narrator-author wax poetic about Macabea (which is what I appreciate, deeply, about this book), rather than another “tired” soliloquy about how hard it is to write a book, character, etc.

Here’s where meta works for me: when it calls attention to the reader during the process of reading, as opposed to the “writer-narrator” character during the process of writing-narrating. Calvino does this extremely well, as does Sorrentino, etc etc. Also, yes, meta works when it defamiliarizes. So, rather than say metafiction is old or failing, maybe I should say that I’m through with the pining, sad, struggling writer writing about writing. (To note, I don’t think Lispector does this. I do think Sal P. does though.)

Here’s where meta works for me: when it calls attention to the reader during the process of reading, as opposed to the “writer-narrator” character during the process of writing-narrating. Calvino does this extremely well, as does Sorrentino, etc etc. Also, yes, meta works when it defamiliarizes. So, rather than say metafiction is old or failing, maybe I should say that I’m through with the pining, sad, struggling writer writing about writing. (To note, I don’t think Lispector does this. I do think Sal P. does though.)

oh yes i see. that metafictional aspect of hour of the star. yes but to me when i read it i think of lispector being at the end of her life, dying from cancer, and returning to her childhood, in a way, to those girls she observed in sao paolo, and then wondering at the futility of writing. to me that’s very powerful, but it is the first aspect you mention (the male narrator/god) that i find most powerful about hour of the star.

oh yes i see. that metafictional aspect of hour of the star. yes but to me when i read it i think of lispector being at the end of her life, dying from cancer, and returning to her childhood, in a way, to those girls she observed in sao paolo, and then wondering at the futility of writing. to me that’s very powerful, but it is the first aspect you mention (the male narrator/god) that i find most powerful about hour of the star.

“Bombs that look like people.” That’s a really good conceit and sounds amazing. But what’s the “they” in “they have to work without the bomb thing”? The characters that the bombs resemble?

“Bombs that look like people.” That’s a really good conceit and sounds amazing. But what’s the “they” in “they have to work without the bomb thing”? The characters that the bombs resemble?

Your translator character in “Changing” is not this pining writer. Seems to me her reflections on translation are more abt foregrounding struggles or tensions (and also a playfulness) related to negotiating identity, ethnicity, generationality, family, gender, etc, and although she can be read as a distinct writer-character, she can also be read as continuous w/ the other girl/girls in the text, all of which I think gives the text more depth. …Feel like this conversation abt whether meta “works” is always going to be very contextual and text-specific for me. …I enjoy your exchange w/ Kate above, even though I haven’t read either book.

Your translator character in “Changing” is not this pining writer. Seems to me her reflections on translation are more abt foregrounding struggles or tensions (and also a playfulness) related to negotiating identity, ethnicity, generationality, family, gender, etc, and although she can be read as a distinct writer-character, she can also be read as continuous w/ the other girl/girls in the text, all of which I think gives the text more depth. …Feel like this conversation abt whether meta “works” is always going to be very contextual and text-specific for me. …I enjoy your exchange w/ Kate above, even though I haven’t read either book.

My two cents: People of Paper felt fresh and delicious to me, even the meta-intrusion. I fell in love with it, and I still feel that little tingle whenever anyone talks about it. Which does nothing to further this discussion except maybe prove to me that “meta,” which I only sometimes have terrific patience for, can be the most beautiful intrusion.

My two cents: People of Paper felt fresh and delicious to me, even the meta-intrusion. I fell in love with it, and I still feel that little tingle whenever anyone talks about it. Which does nothing to further this discussion except maybe prove to me that “meta,” which I only sometimes have terrific patience for, can be the most beautiful intrusion.

I had to look up what Metafiction was and I find that I’ve read a lot of it. I liked some of it and think if you try to write metafiction it will come out like shit and smell worse.

I had to look up what Metafiction was and I find that I’ve read a lot of it. I liked some of it and think if you try to write metafiction it will come out like shit and smell worse.

Probably obvious, but: nothing that is in the book isn’t in the book. It’s all meta and none of it is meta. The narratorial movement of pulling the curtain aside is just a movement, a narrative action that takes place in the world of the book, and definitely nothing more profound, no matter how “deep” (this seems actually the wrong word– it doesn’t go deep at all: it extends outward, doesn’t it?) it goes. The fact that it (asynchronously, it must be said, thus making it explicitly fictional even within its own conceit) acknowledges the act that the reader supposes the writer to be engaged in, or vice versa, does not make it any more or less interesting as a piece of the reading experience, and, as Lily demonstrates, no less the object of scrutiny on the part of the experienced reader.

Do we need it (the metafictional element)? Or not? Is this important? Does it matter to us that it is important?

Probably obvious, but: nothing that is in the book isn’t in the book. It’s all meta and none of it is meta. The narratorial movement of pulling the curtain aside is just a movement, a narrative action that takes place in the world of the book, and definitely nothing more profound, no matter how “deep” (this seems actually the wrong word– it doesn’t go deep at all: it extends outward, doesn’t it?) it goes. The fact that it (asynchronously, it must be said, thus making it explicitly fictional even within its own conceit) acknowledges the act that the reader supposes the writer to be engaged in, or vice versa, does not make it any more or less interesting as a piece of the reading experience, and, as Lily demonstrates, no less the object of scrutiny on the part of the experienced reader.

Do we need it (the metafictional element)? Or not? Is this important? Does it matter to us that it is important?

I think a problem with a lot of metafiction is that it centralizes the reveal, which is tiring and not particularly interesting. It also has the counterintuitive effect of removing any emotional weight from the narrative so that after seeing this ‘trick’ performed a couple of times you start to no longer care. I think meta-fiction can still be a powerful tool and do interesting things but it needs to balance with the narrrative…it’s another function and not the attention seeking primary purpose. If that makes sense. I think two good examples of this kind of meta fiction would be the Agota Kristoff trilogy ‘The book of lies’ and Dennis Cooper’s ‘guide’. I actually wrote an essay about the use of meta-fiction in Guide here (http://transductions.net/2010/03/04/dennis-coopers-guide/) that tries to address how Cooper avoids falling into that trap.

I hope that no one minds me putting the link in there.

Really nice post Lily, thanks

I think a problem with a lot of metafiction is that it centralizes the reveal, which is tiring and not particularly interesting. It also has the counterintuitive effect of removing any emotional weight from the narrative so that after seeing this ‘trick’ performed a couple of times you start to no longer care. I think meta-fiction can still be a powerful tool and do interesting things but it needs to balance with the narrrative…it’s another function and not the attention seeking primary purpose. If that makes sense. I think two good examples of this kind of meta fiction would be the Agota Kristoff trilogy ‘The book of lies’ and Dennis Cooper’s ‘guide’. I actually wrote an essay about the use of meta-fiction in Guide here (http://transductions.net/2010/03/04/dennis-coopers-guide/) that tries to address how Cooper avoids falling into that trap.

I hope that no one minds me putting the link in there.

Really nice post Lily, thanks

Tim — yes. They have to work as the people they seem to be. It’s like how when you watch Battlestar Galactica, everything works even if they aren’t in space fighting robots that look like people — even if they’re just a family, or just a military, or etc. Being in space after the apocalypse just makes it better.

Tim — yes. They have to work as the people they seem to be. It’s like how when you watch Battlestar Galactica, everything works even if they aren’t in space fighting robots that look like people — even if they’re just a family, or just a military, or etc. Being in space after the apocalypse just makes it better.

* I should probably amend that to read:

Does the book/story/etc. need it (the metafictional element)?

but anthropomorphizing is often distasteful.

* I should probably amend that to read:

Does the book/story/etc. need it (the metafictional element)?

but anthropomorphizing is often distasteful.

Right — another way of looking at this is that all fiction is meta, some just hides it better. My favorite fiction tends to have a subtle meta element in that the characters and narrator seem vaguely aware of their medium, and are capable of acting within it as much as they act within the narrative itself, without ever explicitly saying, “HI I AM IN A STORY.” I wrote a longish thing about this a while ago, comparing it to the way actors like Zero Mostel, Gene Wilder, Steve Martin, etc. seemed very comfortable in the classic comedies acknowledging that they were actors on screen and bodies performing in addition to being the characters. There’s something very powerful about a fiction that knows how best to be itself, and this always has a little bit of the meta buzz to it, I think.

Right — another way of looking at this is that all fiction is meta, some just hides it better. My favorite fiction tends to have a subtle meta element in that the characters and narrator seem vaguely aware of their medium, and are capable of acting within it as much as they act within the narrative itself, without ever explicitly saying, “HI I AM IN A STORY.” I wrote a longish thing about this a while ago, comparing it to the way actors like Zero Mostel, Gene Wilder, Steve Martin, etc. seemed very comfortable in the classic comedies acknowledging that they were actors on screen and bodies performing in addition to being the characters. There’s something very powerful about a fiction that knows how best to be itself, and this always has a little bit of the meta buzz to it, I think.

I cannot recommend The Complete Works of Marvin K. Mooney enough. It, to me, was and is the most liberating show of self-consciousness.

I cannot recommend The Complete Works of Marvin K. Mooney enough. It, to me, was and is the most liberating show of self-consciousness.

I’m not sure I agree with this. Most of the time, if meta-fiction (or any other major element) is being used effectively it IS part of the story and can’t be simply extracted. If a story works perfectly without metafiction, why would you then add it? Isn’t that the point at which metafiction is just a tacked on decoration? Metafiction should be essential to the piece if you are going to use it.

You could substitute a lot of terms for metafiction there and the same would apply, I think.

I’m not sure I agree with this. Most of the time, if meta-fiction (or any other major element) is being used effectively it IS part of the story and can’t be simply extracted. If a story works perfectly without metafiction, why would you then add it? Isn’t that the point at which metafiction is just a tacked on decoration? Metafiction should be essential to the piece if you are going to use it.

You could substitute a lot of terms for metafiction there and the same would apply, I think.

I agree, Ken. I’m midway through, and I’m really enjoying it. I think it’s the humor that works for me, which is why I think I appreciate Sorrentino’s metafiction so much.

I agree, Ken. I’m midway through, and I’m really enjoying it. I think it’s the humor that works for me, which is why I think I appreciate Sorrentino’s metafiction so much.

Yes, I was thinking abt Guide earlier.

Yes, I was thinking abt Guide earlier.

Lily, have you read any Mo Yan? Too often I think you’re exactly right–that metafiction is obsessed with it’s own meta-ness and becomes boring and a “trick.” But with Mo Yan, he jumps in and out of the (rich and wonderful) stories he’s telling, sometimes as Mo Yan the author, sometimes as a totally different Mo Yan, and it never feels like a trick. I think it serves to enhance the stories because he’s obviously so eager to tell them, to explain them, that he can’t keep his hands off, as an author and a trickster, and there’s something about that attitude that’s very infectious and makes you enjoy the stories all the more.

Lily, have you read any Mo Yan? Too often I think you’re exactly right–that metafiction is obsessed with it’s own meta-ness and becomes boring and a “trick.” But with Mo Yan, he jumps in and out of the (rich and wonderful) stories he’s telling, sometimes as Mo Yan the author, sometimes as a totally different Mo Yan, and it never feels like a trick. I think it serves to enhance the stories because he’s obviously so eager to tell them, to explain them, that he can’t keep his hands off, as an author and a trickster, and there’s something about that attitude that’s very infectious and makes you enjoy the stories all the more.

It’s a pretty big leap from observing that a book has metafictional elements, to saying that the book itself “is metafiction”, ie that the metafictional aspect is what overwhelmingly defines the book. To call the Hour of the Star metafiction is (in my opinion) reductive and injust to a great novel. For a second-rate, bland, and utterly derivative work like People of Paper, the description is probably fitting (though to be fair, dude at least had the decency to cite some of his sources).

It’s a pretty big leap from observing that a book has metafictional elements, to saying that the book itself “is metafiction”, ie that the metafictional aspect is what overwhelmingly defines the book. To call the Hour of the Star metafiction is (in my opinion) reductive and injust to a great novel. For a second-rate, bland, and utterly derivative work like People of Paper, the description is probably fitting (though to be fair, dude at least had the decency to cite some of his sources).

meta slaps you with its concept when youre a virgin. but the concept gets old once youve seen it enough, as do all concepts. eventually meta stops being a concept and becomes style, and suddenly there are an infinite number of ways to use it interestingly.

meta slaps you with its concept when youre a virgin. but the concept gets old once youve seen it enough, as do all concepts. eventually meta stops being a concept and becomes style, and suddenly there are an infinite number of ways to use it interestingly.

I think that’s right but that it also sort of misses the point. Certainly in this scenario one wants the metafiction, once it is present, to feel absolutely necessary, and indeed to *be* absolutely necessary to the text-as-it-is.

To the extent that Light Boxes works as a metafiction (and it mostly did for me, although there were times I would have liked to see that element diminished) it’s because its contents would still be thrilling without that skew. It doesn’t matter why someone has his face ripped open and his mouth stuffed with snow. That’s great on its own terms. A man riding a balloon up to a hole in the sky is great whether it’s God waiting for him up there, his author, or a space alien (and note that the differences between these things in story terms are fairly small). In metafiction generally, the author takes on a sort of father role or something like it, because it’s compelling to watch a character rage against his/her father. In any well-written metafiction, the meta-ness should seem inextricable from the text, but it should at the same time probably have underlying narrative shapes more robust than the gimmick. These are what stop it from *becoming* a gimmick.

I think that’s right but that it also sort of misses the point. Certainly in this scenario one wants the metafiction, once it is present, to feel absolutely necessary, and indeed to *be* absolutely necessary to the text-as-it-is.

To the extent that Light Boxes works as a metafiction (and it mostly did for me, although there were times I would have liked to see that element diminished) it’s because its contents would still be thrilling without that skew. It doesn’t matter why someone has his face ripped open and his mouth stuffed with snow. That’s great on its own terms. A man riding a balloon up to a hole in the sky is great whether it’s God waiting for him up there, his author, or a space alien (and note that the differences between these things in story terms are fairly small). In metafiction generally, the author takes on a sort of father role or something like it, because it’s compelling to watch a character rage against his/her father. In any well-written metafiction, the meta-ness should seem inextricable from the text, but it should at the same time probably have underlying narrative shapes more robust than the gimmick. These are what stop it from *becoming* a gimmick.

But what does it mean to say Light Boxes work would be thrilling without the metafiction, when the metafiction is so integral? The contents would be quite different, they would have to change. If you took out that aspect, the book wouldn’t have its story arc and many of the elements would have to change or be removed.

Or take an example like If On A Winter’s Night by Calvino. What does it even mean to say the contents would be trilling without the metafiction? The metafiction IS the story? Ditto with Sorrentino’s The Moon In It’s Flight.

The Moon in It’s Flight is a great story, but some hypothetical other story without that element might just be a bland teenage romance story.

But what does it mean to say Light Boxes work would be thrilling without the metafiction, when the metafiction is so integral? The contents would be quite different, they would have to change. If you took out that aspect, the book wouldn’t have its story arc and many of the elements would have to change or be removed.

Or take an example like If On A Winter’s Night by Calvino. What does it even mean to say the contents would be trilling without the metafiction? The metafiction IS the story? Ditto with Sorrentino’s The Moon In It’s Flight.

The Moon in It’s Flight is a great story, but some hypothetical other story without that element might just be a bland teenage romance story.

As I said, to me you could insert other terms into this discussion (minimalist prose, magical realism, voicey language, etc.) To me it doesn’t make much sense to say One Hundred Years of Solitude would work without the magical realism or that Tao Lin would work without the minimalist prose or that Calvino would work without the metafiction… these works would simply be totally different without those elements.

As I said, to me you could insert other terms into this discussion (minimalist prose, magical realism, voicey language, etc.) To me it doesn’t make much sense to say One Hundred Years of Solitude would work without the magical realism or that Tao Lin would work without the minimalist prose or that Calvino would work without the metafiction… these works would simply be totally different without those elements.

I guess what I’m trying to express is that in narrative-oriented fiction, the narrative itself (the shapes, the people, etc.) should be strong without a given slant, or the slant will likely fail, come off as a crutch. Does that make sense?

I guess what I’m trying to express is that in narrative-oriented fiction, the narrative itself (the shapes, the people, etc.) should be strong without a given slant, or the slant will likely fail, come off as a crutch. Does that make sense?

In other words, it’s not that you write a “conventional” story and then spread the isolated element on like jam, it’s that you have to be so good that you don’t need it before you are likely to be able to do it right. The movie Memento sucks because it wouldn’t be any good without the nonlinear stuff — which isn’t to say that you can strip the nonlinear out, it’s just a way of saying the underlying story and characters are not very good.

In other words, it’s not that you write a “conventional” story and then spread the isolated element on like jam, it’s that you have to be so good that you don’t need it before you are likely to be able to do it right. The movie Memento sucks because it wouldn’t be any good without the nonlinear stuff — which isn’t to say that you can strip the nonlinear out, it’s just a way of saying the underlying story and characters are not very good.

Mike, Could you be possibly be alluding to Shane Jones’ “Light Boxes”? Shit, if Plascencia is derivative, what is Jones?

Mike, Could you be possibly be alluding to Shane Jones’ “Light Boxes”? Shit, if Plascencia is derivative, what is Jones?

i liked “near to the wild heart.” would like to read more lispector.

i liked “near to the wild heart.” would like to read more lispector.

http://htmlgiant.com/craft-notes/meta-blah/#comment-66834

http://htmlgiant.com/craft-notes/meta-blah/#comment-66834

I’m in agreement with Lincoln, here, although I see what you’re saying, Mike: like I say in a comment below (and like you say earlier), I think the “it has to be so good that you don’t need it” rule of thumb is extremely useful in a creative writing classroom. It helps steer young writers (who are in the process of composing new works) away from the temptation of using meta to unsuccessfully trick out/pimp a story that maybe wouldn’t work no matter what.

(I agree: no matter how many explosions you add to Memento, it’s still going to be lame-o.)

But this rule of thumb is maybe not as useful to apply when breaking down the works of geniuses like Calvino. It’s perhaps less useful to think about the work being strong “without the slant.” The work is not strong “without the given slant” because the work is strong “WITH the given slant”– in fact, it’s SO strong with that slant that one can’t separate the slant from the work itself. It’s all woven together wonderfully.

Which is pretty much what Lincoln’s saying, and why I agree with him.

I’m in agreement with Lincoln, here, although I see what you’re saying, Mike: like I say in a comment below (and like you say earlier), I think the “it has to be so good that you don’t need it” rule of thumb is extremely useful in a creative writing classroom. It helps steer young writers (who are in the process of composing new works) away from the temptation of using meta to unsuccessfully trick out/pimp a story that maybe wouldn’t work no matter what.

(I agree: no matter how many explosions you add to Memento, it’s still going to be lame-o.)

But this rule of thumb is maybe not as useful to apply when breaking down the works of geniuses like Calvino. It’s perhaps less useful to think about the work being strong “without the slant.” The work is not strong “without the given slant” because the work is strong “WITH the given slant”– in fact, it’s SO strong with that slant that one can’t separate the slant from the work itself. It’s all woven together wonderfully.

Which is pretty much what Lincoln’s saying, and why I agree with him.