Craft Notes

Michael Kimball Guest Lecture #4: Story and Plot

“Fuck the plot.” Edna O’Brien says that in a Paris Review interview. She then goes on to say this: “What matters is the imaginative truth.” I don’t know what she means, exactly, by “imaginative truth,” but I can imagine what she means.

It reminds me of something that somebody told me Rick Whitaker said: “Plot tells you how their life turns out. What the fuck do I care about how their life turns out? I want to know their heart.”

And that reminds me of this quote from Andy Devine: “We all know how the story ends. If you have the baby, then the baby will die. If you fall in love, then the love will end.”

In spite of my affection for those three quotes, I still like to think about story and plot. I still like it when things happen in fiction. In fact, I have always thought that one of the great things about being a fiction writer is that you can make anything happen.

Before this goes too far, here are a couple of definitions: story is what happens in chronological order; plot is the story—however it is arranged in the work of fiction. The Russian Formalists call these two things the fabula (“elements of action and event in their natural chronological and causal order”) and the sujet (“the rearranged manner of their textual presentation created by artistic compositional patterns”).

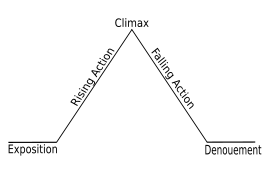

Here’s some more on plot: As Aristotle is said to have said (in another language), there should be a beginning, a middle, and an end. Gustav Freytag tried to improve upon that and broke plot down into five parts—exposition (background information, setting), rising action (conflict, complications), climax (crisis, turning point), falling action (anticlimax), denouement (resolution). Freytag’s thing is usually described as a pyramid or triangle.

There’s a revision of Freytag that is in the shape of an inverted checkmark. The inverted checkmark has the same five parts as the pyramid, but the falling action and resolution take place much faster, which I like. I hate it when the ending takes longer to end than it needs to. If it starts to take too long for a story or a novel to end, then I begin to feel manipulated by the writer and I never want to feel that (even though I know that is what is happening).

OK, I’d like to create some new structure or shape that cuts out the exposition and shortens the ending (does anybody have an idea for what shape this would be?). The fiction has to begin somewhere, but I like beginning with the conflict or the complicated situation. I want to get right into it and let any information that we need to know come out when we need to know it. This is a bit of a jump, but that;s why I like this quote from Kurt Vonnegut: “Start as close to the end as possible.” And this nearly identical quote from Chris Offut: “The secret is to start a story near the ending.”

Let’s move on. As readers, we are mostly conditioned to receive narrative in chronological terms. Most works of fiction are chronological, though, of course, there are plenty of exceptions. And even if the fiction isn’t presented in chronological terms, the reader will generally put the story in chronological order in their reading. Generally, the reader can’t help it. I don’t know how much chronology matters, but it always makes me think about flashbacks. I had a writing teacher who said that a fiction writer should never use a flashback. She said that a flashback’s darker purpose is exposition or explanation, which stalls the narrative. She advised this: If you need what’s back there in the flashback, then start the story back there. Janet Burroway doesn’t say that the fiction writer should never use a flashback, but she almost does: “Dialogue, brief summary, a reference or detail can often tell us all we need to know, and when that is the case, a flashback becomes cumbersome.”

I needed to get flashbacks out of the way. I want to talk about the narrative moving forward. Connie Willis (via Opium) says this: “Every sentence should set the tone, define the character, and advance the plot. If it’s not doing all three, fix it, or cut it.” Kurt Vonnegut (from Bagombo Snuff Box) says something similar: “Every sentence must do one of two things—reveal character or advance the action.”

Vonnegut also said this: “I don’t praise plots as accurate representations of life, but as ways to keep readers reading. When I used to teach creative writing, I would tell the students to make their characters want something right away — even if it’s only a glass of water.” Now a character getting a glass of water may not be enough to keep the reader reading, but there’s still a useful idea there, especially if it’s combined with this quote from Ernest Hemingway: “Never confuse movement with action.”

I often tell writers that they have to make the reader want to turn the page and there are plenty of ways to do that. It can be because the reader wants to find out what happens next or because the writing is so funny that the reader wants the next laugh or because the writing is so amazing that the reader wants the next amazement. That is, there are plenty of great books that have been written without using story and plot in traditional ways—Stanley G. Crawford’s Some Instructions and David Markson’s late quartet of novels are good examples of that. That is, what is on the page can be anything, but it has to be something.

Lots of writers and teachers tie that something to a character. Here’s Janet Burroway on that: “In fiction, in order to engage our attention and sympathy, the protagonist must want, and want intensely. The thing that the character wants need not be violent or spectacular; it is the intensity of the wanting that introduces an element of danger.” That is, I think, a riff on a quote from Aristotle’s Poetics, but I couldn’t find it. Anyway, Luke Whisnant says it pretty simply: “Plot arises from the character’s pursuit of her desires.”

Doug Lawson says something similar from a different angle: “Often I’ll find clues to where the story might go by figuring out where the characters would rather not go.” That makes me think of this Don DeLillo quote (via Lee Klein): “I feel that a novel tells you what it wants to be . . . It’s really the purest sort of impulse — a question of what the novel seems to want — and this novel demanded economy.” And that makes me think of this from Joseph Scapellato, which maybe says it best: “The story is smarter than you.”

How do you think about story, about plot, about a character’s desire, about books that work without using story and plot in traditional ways, etc.?

Tags: chris offutt, Don DeLillo, edna o'brien, plot

i dont get behind the character-wanting thing too much. i think i have a tendency to make setting more important than characters. i have a setting or atmosphere in my head im interested in conveying. my characters tend to be cardboards for the sake of the setting. it takes a deliberate effort for me to make a character be important to the story. maybe what i’m doing is seeing intense desire as selfishness, and i say to my character, consider the world around you, here let me make it interesting for you.

i dont get behind the character-wanting thing too much. i think i have a tendency to make setting more important than characters. i have a setting or atmosphere in my head im interested in conveying. my characters tend to be cardboards for the sake of the setting. it takes a deliberate effort for me to make a character be important to the story. maybe what i’m doing is seeing intense desire as selfishness, and i say to my character, consider the world around you, here let me make it interesting for you.

i dont get behind the character-wanting thing too much. i think i have a tendency to make setting more important than characters. i have a setting or atmosphere in my head im interested in conveying. my characters tend to be cardboards for the sake of the setting. it takes a deliberate effort for me to make a character be important to the story. maybe what i’m doing is seeing intense desire as selfishness, and i say to my character, consider the world around you, here let me make it interesting for you.

Very good post. Thanks, Michael. There are certainly many young writers, including myself, whose work would benefit from honing in even more on their characters, rather than letting theme or language or literary conceit rule the day. That could lead to more narrative, more action. I take the most stock in Edna O’Brien’s quote about “imaginative truth.” Like many great rhetoricians, Edna understands that a point is made more forcefully and memorably when one does not deign to cushion the argumentative blow or to explain away (for the benefit of simple minds and the easily offended) the subtle nuances. She knows that the writers she’s trying to reach have brains, and know that when she says “Fuck the plot!” she doesn’t mean stories should have no plot, no narrative—rather, she’s saying, reorient your focus, stop thinking about established forms and end products and start thinking about a way of writing that has urgent aims but no rules or set forms, the way of imaginative truth.

Very good post. Thanks, Michael. There are certainly many young writers, including myself, whose work would benefit from honing in even more on their characters, rather than letting theme or language or literary conceit rule the day. That could lead to more narrative, more action. I take the most stock in Edna O’Brien’s quote about “imaginative truth.” Like many great rhetoricians, Edna understands that a point is made more forcefully and memorably when one does not deign to cushion the argumentative blow or to explain away (for the benefit of simple minds and the easily offended) the subtle nuances. She knows that the writers she’s trying to reach have brains, and know that when she says “Fuck the plot!” she doesn’t mean stories should have no plot, no narrative—rather, she’s saying, reorient your focus, stop thinking about established forms and end products and start thinking about a way of writing that has urgent aims but no rules or set forms, the way of imaginative truth.

Very good post. Thanks, Michael. There are certainly many young writers, including myself, whose work would benefit from honing in even more on their characters, rather than letting theme or language or literary conceit rule the day. That could lead to more narrative, more action. I take the most stock in Edna O’Brien’s quote about “imaginative truth.” Like many great rhetoricians, Edna understands that a point is made more forcefully and memorably when one does not deign to cushion the argumentative blow or to explain away (for the benefit of simple minds and the easily offended) the subtle nuances. She knows that the writers she’s trying to reach have brains, and know that when she says “Fuck the plot!” she doesn’t mean stories should have no plot, no narrative—rather, she’s saying, reorient your focus, stop thinking about established forms and end products and start thinking about a way of writing that has urgent aims but no rules or set forms, the way of imaginative truth.

I am enjoying these pieces, Michael. Please keep them coming.

I am enjoying these pieces, Michael. Please keep them coming.

I am enjoying these pieces, Michael. Please keep them coming.

that’s what she said

that’s what she said

that’s what she said

Michael, my writing prof said the same thing about flashbacks. He excoriated us every time we tried using them. I try never to use them, nearly 20 years after taking his class.

My stories are plot heavy, or so I’ve been told, even those that have been in elimae. I can’t seem to write stories that don’t have plot. I saw a great quote by Steve Himmer earlier this year about new year resolutions. I can’t find it and won’t attempt to quote (he checks here sometimes!) but basically he said he wanted to feel better about his own way of writing and not try to tailor it to keep up with the joneses (shit now i’m paraphrasing). I’m following suit. I think about stories in terms of what happens. I always have and think I always will. I love reading others who do so much more with language but, yeah, I don’t like the stories I write when I try to emulate them.

Michael, my writing prof said the same thing about flashbacks. He excoriated us every time we tried using them. I try never to use them, nearly 20 years after taking his class.

My stories are plot heavy, or so I’ve been told, even those that have been in elimae. I can’t seem to write stories that don’t have plot. I saw a great quote by Steve Himmer earlier this year about new year resolutions. I can’t find it and won’t attempt to quote (he checks here sometimes!) but basically he said he wanted to feel better about his own way of writing and not try to tailor it to keep up with the joneses (shit now i’m paraphrasing). I’m following suit. I think about stories in terms of what happens. I always have and think I always will. I love reading others who do so much more with language but, yeah, I don’t like the stories I write when I try to emulate them.

Michael, my writing prof said the same thing about flashbacks. He excoriated us every time we tried using them. I try never to use them, nearly 20 years after taking his class.

My stories are plot heavy, or so I’ve been told, even those that have been in elimae. I can’t seem to write stories that don’t have plot. I saw a great quote by Steve Himmer earlier this year about new year resolutions. I can’t find it and won’t attempt to quote (he checks here sometimes!) but basically he said he wanted to feel better about his own way of writing and not try to tailor it to keep up with the joneses (shit now i’m paraphrasing). I’m following suit. I think about stories in terms of what happens. I always have and think I always will. I love reading others who do so much more with language but, yeah, I don’t like the stories I write when I try to emulate them.

Although some of my favorite novels or stories have subverted causal logic and plot in interesting ways, there is beauty in a classically structured story. Plus, the stories and books that do away with conventional plotting would have nothing to play against without this set structure. So, even though most of the things I have been reading lately don’t follow plot and story in traditional ways, I appreciate how the writer’s work and my pleasure in reading are both indebted to classic narrative structure.

Although some of my favorite novels or stories have subverted causal logic and plot in interesting ways, there is beauty in a classically structured story. Plus, the stories and books that do away with conventional plotting would have nothing to play against without this set structure. So, even though most of the things I have been reading lately don’t follow plot and story in traditional ways, I appreciate how the writer’s work and my pleasure in reading are both indebted to classic narrative structure.

shit, i didn’t mean “no plot.” i mean stories that have things going on but, with a gun to my head, i couldn’t say for sure what the story was “about.” time to go read to the blind. bye.

shit, i didn’t mean “no plot.” i mean stories that have things going on but, with a gun to my head, i couldn’t say for sure what the story was “about.” time to go read to the blind. bye.

Although some of my favorite novels or stories have subverted causal logic and plot in interesting ways, there is beauty in a classically structured story. Plus, the stories and books that do away with conventional plotting would have nothing to play against without this set structure. So, even though most of the things I have been reading lately don’t follow plot and story in traditional ways, I appreciate how the writer’s work and my pleasure in reading are both indebted to classic narrative structure.

shit, i didn’t mean “no plot.” i mean stories that have things going on but, with a gun to my head, i couldn’t say for sure what the story was “about.” time to go read to the blind. bye.

Whenever I think about this stuff, I try to stop thinking about it as fast as I can. Whenever I hear a rule declaimed, my mind spits out all the many rule breakers.

To paraphrase Frank Conroy paraphrasing George Orwell: there’s only one real rule in fiction: whatever you do, you’ve gotta pull it off.

(A note to the puerile: “pull it off” ain’t wanking — it’s about getting a reader off.)

But how do you get a reader off? Maybe if you simply present a deeply imagined world in language that’s tight and engaging and unpredictable, that seems to organically relay “magic, story, wisdom” (see link below to Nabokov’s “Good Readers and Good Writers” essay), paying attention to all the little resonant hammerings you make on the metal tube the reader’s scurrying through from first word to last, reader and writer will have a mutually satisfying literary experience (see Jimmy’s recent post re: Kafka’s phrase, “intercourse with ghosts”)

http://cmsweb1.loudoun.k12.va.us/5222082812383487/lib/5222082812383487/Nabokov_essay.doc

I like an unanswered question, but that’s about all I need. And that can be anything, a stirring, a flux, a flutter of a conflict.

The more I get into individual sentences (as a reader) the less I need anything approaching Triangle plot, etc.

I will say plot and theme are not mutually exclusive. Some of the best books work the sentence, the mind, and make me turn the page.

I like an unanswered question, but that’s about all I need. And that can be anything, a stirring, a flux, a flutter of a conflict.

The more I get into individual sentences (as a reader) the less I need anything approaching Triangle plot, etc.

I will say plot and theme are not mutually exclusive. Some of the best books work the sentence, the mind, and make me turn the page.

I like an unanswered question, but that’s about all I need. And that can be anything, a stirring, a flux, a flutter of a conflict.

The more I get into individual sentences (as a reader) the less I need anything approaching Triangle plot, etc.

I will say plot and theme are not mutually exclusive. Some of the best books work the sentence, the mind, and make me turn the page.

cute! sophisticated!

cute! sophisticated!

cute! sophisticated!

The shape you’re looking for, Michael, that “cuts out the exposition and shortens the ending” would be a mirror image of the square root symbol, yes? Good luck with that. About plot/movement/character/story: Yiyun Li once mentioned after a reading, by way of Marilynne Robinson, that every sentence–every object–in the story must do *at least* three things. A high, good bar, I say.

The shape you’re looking for, Michael, that “cuts out the exposition and shortens the ending” would be a mirror image of the square root symbol, yes? Good luck with that. About plot/movement/character/story: Yiyun Li once mentioned after a reading, by way of Marilynne Robinson, that every sentence–every object–in the story must do *at least* three things. A high, good bar, I say.

The shape you’re looking for, Michael, that “cuts out the exposition and shortens the ending” would be a mirror image of the square root symbol, yes? Good luck with that. About plot/movement/character/story: Yiyun Li once mentioned after a reading, by way of Marilynne Robinson, that every sentence–every object–in the story must do *at least* three things. A high, good bar, I say.

The character-desire thing is a common way to think about story/plot, though there are so many ways to go at it within that framework. But I like your different take on this. It makes me think of those books where some reviewer will say the setting was the main character, or another character, or something like that.

The character-desire thing is a common way to think about story/plot, though there are so many ways to go at it within that framework. But I like your different take on this. It makes me think of those books where some reviewer will say the setting was the main character, or another character, or something like that.

The character-desire thing is a common way to think about story/plot, though there are so many ways to go at it within that framework. But I like your different take on this. It makes me think of those books where some reviewer will say the setting was the main character, or another character, or something like that.

Thanks, Stephen. And thanks for articulating that O’Brien isn’t saying no plot. She isn’t. She is saying that there are lots of ways besides plot to create a novel.

Thanks, Stephen. And thanks for articulating that O’Brien isn’t saying no plot. She isn’t. She is saying that there are lots of ways besides plot to create a novel.

Thanks, Stephen. And thanks for articulating that O’Brien isn’t saying no plot. She isn’t. She is saying that there are lots of ways besides plot to create a novel.

Thanks, Kyle. The next one, I think, is Language and Sentences.

Thanks, Kyle. The next one, I think, is Language and Sentences.

Thanks, Kyle. The next one, I think, is Language and Sentences.

Nice point, Neil, about new takes on plot and story playing against the conventions. I also think that we all know these conventions so well that a new work that depends on the classic narrative structure has to be exceptional–at least for me. I just finished a novel with a classic structure that I mostly loved, but it really felt as if the author gave away some of the greatness in the too-long ending, too many pages on falling action and denouement, even though it first Freytag perfectly.

Nice point, Neil, about new takes on plot and story playing against the conventions. I also think that we all know these conventions so well that a new work that depends on the classic narrative structure has to be exceptional–at least for me. I just finished a novel with a classic structure that I mostly loved, but it really felt as if the author gave away some of the greatness in the too-long ending, too many pages on falling action and denouement, even though it first Freytag perfectly.

Nice point, Neil, about new takes on plot and story playing against the conventions. I also think that we all know these conventions so well that a new work that depends on the classic narrative structure has to be exceptional–at least for me. I just finished a novel with a classic structure that I mostly loved, but it really felt as if the author gave away some of the greatness in the too-long ending, too many pages on falling action and denouement, even though it first Freytag perfectly.

Hey Sean, I completely agree–it can be anything. And probably none of this–story, plot, theme, language, syntax, diction, character, etc.–is mutually exclusive.

Hey Sean, I completely agree–it can be anything. And probably none of this–story, plot, theme, language, syntax, diction, character, etc.–is mutually exclusive.

Hey Sean, I completely agree–it can be anything. And probably none of this–story, plot, theme, language, syntax, diction, character, etc.–is mutually exclusive.

Stacy, maybe an inverted mirror-image of the square root symbol (√)? Or maybe, in my heart of hearts, I just want this: /.

I like that Marilynne Robinson quote. There’s a bunch of that stuff coming up in #5 I think.

Stacy, maybe an inverted mirror-image of the square root symbol (√)? Or maybe, in my heart of hearts, I just want this: /.

I like that Marilynne Robinson quote. There’s a bunch of that stuff coming up in #5 I think.

Stacy, maybe an inverted mirror-image of the square root symbol (√)? Or maybe, in my heart of hearts, I just want this: /.

I like that Marilynne Robinson quote. There’s a bunch of that stuff coming up in #5 I think.

I really like these, BTW. A good bundle for my students.

I really like these, BTW. A good bundle for my students.

I really like these, BTW. A good bundle for my students.

Excuse me for saying so, sir, but your EXPOSITION – RISING ACTION – CLIMAX – FALLING ACTION – DENOUEMENT paradigm is incomplete to the point of being antiquated. For the most part the modern trend in approaching this classic ‘Greek Tragedy’ formulation changed in the late 19th century. The new formulation (evidenced in practice by authors too numerous to mention) is based on a new classic viewpoint, in that the idea of simply a BEGINNING, MIDDLE and END doesn’t function effectively in a novel length story, due to the fact that it is…a novel length story. It’s not a short-story. It’s a long-story, and the means of being effective in a long-story are far more evolved than oversimplifications like “beginning, middle and end,” and the classic rise and fall of a Greek Tragedy. It’s not that these simple formulations do not function, but simply that they do not function adequately for novels and screenplays. The modern novelist should be aware of the fact that, generally, the gears of storytelling (ie, structural essence) have shifted from a 3-Phase approach (beginning, middle and end) to a 5-Phase approach, and that is the new classic, and the new foundation for elaborations on its new classic method.

Two points also worth mentioning might be:

Why do we need 5-Phases of structure instead of merely 3? Because, what should be the strongest part of a novel length work, a long-story, turns out for most amateur and aspiring authors to be the weakest part — the Great Middle portion of the story. Short stories are short, hence the middle is not a challenge to the well crafted short-story author, but novels are long, and the ‘great middle part’ of the work has to stand up as well as the beginning (ie, The Opening) and the ending (ie, The Main-Event of Resolution and the Finale). Therefore both, the classic Greek Tragedy Paradigm (as you diagrammed it) and the basic BME paradigm had to be rethought and redesigned in actual practice. This was an evolution that began perhaps 125 years ago, but has flowered in our culture over the last 70+ years. It’s pretty much standard. Those who know it have a tendency to turn out bestselling fiction and/or successful films.

Of course this brings up point #2: if you owned a goose that actually did lay golden eggs, to what extent would be willing to even share the fact of that goose’s existence to other people? It goes with the old axiom, when you got a good thing going, keep your mouth shut.

So, for most aspiring authors, plot and structure is an exercise in the esoteric.

Excuse me for saying so, sir, but your EXPOSITION – RISING ACTION – CLIMAX – FALLING ACTION – DENOUEMENT paradigm is incomplete to the point of being antiquated. For the most part the modern trend in approaching this classic ‘Greek Tragedy’ formulation changed in the late 19th century. The new formulation (evidenced in practice by authors too numerous to mention) is based on a new classic viewpoint, in that the idea of simply a BEGINNING, MIDDLE and END doesn’t function effectively in a novel length story, due to the fact that it is…a novel length story. It’s not a short-story. It’s a long-story, and the means of being effective in a long-story are far more evolved than oversimplifications like “beginning, middle and end,” and the classic rise and fall of a Greek Tragedy. It’s not that these simple formulations do not function, but simply that they do not function adequately for novels and screenplays. The modern novelist should be aware of the fact that, generally, the gears of storytelling (ie, structural essence) have shifted from a 3-Phase approach (beginning, middle and end) to a 5-Phase approach, and that is the new classic, and the new foundation for elaborations on its new classic method.

Two points also worth mentioning might be:

Why do we need 5-Phases of structure instead of merely 3? Because, what should be the strongest part of a novel length work, a long-story, turns out for most amateur and aspiring authors to be the weakest part — the Great Middle portion of the story. Short stories are short, hence the middle is not a challenge to the well crafted short-story author, but novels are long, and the ‘great middle part’ of the work has to stand up as well as the beginning (ie, The Opening) and the ending (ie, The Main-Event of Resolution and the Finale). Therefore both, the classic Greek Tragedy Paradigm (as you diagrammed it) and the basic BME paradigm had to be rethought and redesigned in actual practice. This was an evolution that began perhaps 125 years ago, but has flowered in our culture over the last 70+ years. It’s pretty much standard. Those who know it have a tendency to turn out bestselling fiction and/or successful films.

Of course this brings up point #2: if you owned a goose that actually did lay golden eggs, to what extent would be willing to even share the fact of that goose’s existence to other people? It goes with the old axiom, when you got a good thing going, keep your mouth shut.

So, for most aspiring authors, plot and structure is an exercise in the esoteric.

Excuse me for saying so, sir, but your EXPOSITION – RISING ACTION – CLIMAX – FALLING ACTION – DENOUEMENT paradigm is incomplete to the point of being antiquated. For the most part the modern trend in approaching this classic ‘Greek Tragedy’ formulation changed in the late 19th century. The new formulation (evidenced in practice by authors too numerous to mention) is based on a new classic viewpoint, in that the idea of simply a BEGINNING, MIDDLE and END doesn’t function effectively in a novel length story, due to the fact that it is…a novel length story. It’s not a short-story. It’s a long-story, and the means of being effective in a long-story are far more evolved than oversimplifications like “beginning, middle and end,” and the classic rise and fall of a Greek Tragedy. It’s not that these simple formulations do not function, but simply that they do not function adequately for novels and screenplays. The modern novelist should be aware of the fact that, generally, the gears of storytelling (ie, structural essence) have shifted from a 3-Phase approach (beginning, middle and end) to a 5-Phase approach, and that is the new classic, and the new foundation for elaborations on its new classic method.

Two points also worth mentioning might be:

Why do we need 5-Phases of structure instead of merely 3? Because, what should be the strongest part of a novel length work, a long-story, turns out for most amateur and aspiring authors to be the weakest part — the Great Middle portion of the story. Short stories are short, hence the middle is not a challenge to the well crafted short-story author, but novels are long, and the ‘great middle part’ of the work has to stand up as well as the beginning (ie, The Opening) and the ending (ie, The Main-Event of Resolution and the Finale). Therefore both, the classic Greek Tragedy Paradigm (as you diagrammed it) and the basic BME paradigm had to be rethought and redesigned in actual practice. This was an evolution that began perhaps 125 years ago, but has flowered in our culture over the last 70+ years. It’s pretty much standard. Those who know it have a tendency to turn out bestselling fiction and/or successful films.

Of course this brings up point #2: if you owned a goose that actually did lay golden eggs, to what extent would be willing to even share the fact of that goose’s existence to other people? It goes with the old axiom, when you got a good thing going, keep your mouth shut.

So, for most aspiring authors, plot and structure is an exercise in the esoteric.

Tommy Dee, I like that you’re suggesting something that you refuse to explain. Also, it isn’t my paradigm and it is still very much in use. The post is about different ways to think about about story and plot, both historical and contemporary, and it is suggesting that these ideas continue to change.

Tommy Dee, I like that you’re suggesting something that you refuse to explain. Also, it isn’t my paradigm and it is still very much in use. The post is about different ways to think about about story and plot, both historical and contemporary, and it is suggesting that these ideas continue to change.

Tommy Dee, I like that you’re suggesting something that you refuse to explain. Also, it isn’t my paradigm and it is still very much in use. The post is about different ways to think about about story and plot, both historical and contemporary, and it is suggesting that these ideas continue to change.

right. what books are like that? I’m trying to think.

right. what books are like that? I’m trying to think.

right. what books are like that? I’m trying to think.

i think i always had that sense about dahlgren, like all these people are moving around within this other inexplicable character.

i think i always had that sense about dahlgren, like all these people are moving around within this other inexplicable character.

i think i always had that sense about dahlgren, like all these people are moving around within this other inexplicable character.

So you’re talking about Campbellian/monomythical structure. Yeah. Hollywood knows it, people know it; it’s not a secret. And yes, it seems to work on the psyche effectively, but there are always flops. It’s not a hack. It’s a method, and the method must breathe.

So you’re talking about Campbellian/monomythical structure. Yeah. Hollywood knows it, people know it; it’s not a secret. And yes, it seems to work on the psyche effectively, but there are always flops. It’s not a hack. It’s a method, and the method must breathe.

So you’re talking about Campbellian/monomythical structure. Yeah. Hollywood knows it, people know it; it’s not a secret. And yes, it seems to work on the psyche effectively, but there are always flops. It’s not a hack. It’s a method, and the method must breathe.

Plot is for closers.

Plot is for closers.

Plot is for closers.

PLOT IS FOR TINTIN

WHO DOESN’T LIKE TINTIN?

HIS LITTLE WHITE DOG, THAT “O” FACE OF HIS, THE WAY HE’S ALWAYS GETTING KNOCKED AROUND, AND OF COURSE CAPTAIN HADDOCK AND THE PROFESSOR TOO–WHY, IF PLOT IS GOOD ENOUGH FOR TINTIN IT’S GOOD ENOUGH FOR ME, BY GOD!!!

PLOT IS FOR TINTIN

WHO DOESN’T LIKE TINTIN?

HIS LITTLE WHITE DOG, THAT “O” FACE OF HIS, THE WAY HE’S ALWAYS GETTING KNOCKED AROUND, AND OF COURSE CAPTAIN HADDOCK AND THE PROFESSOR TOO–WHY, IF PLOT IS GOOD ENOUGH FOR TINTIN IT’S GOOD ENOUGH FOR ME, BY GOD!!!

PLOT IS FOR TINTIN

WHO DOESN’T LIKE TINTIN?

HIS LITTLE WHITE DOG, THAT “O” FACE OF HIS, THE WAY HE’S ALWAYS GETTING KNOCKED AROUND, AND OF COURSE CAPTAIN HADDOCK AND THE PROFESSOR TOO–WHY, IF PLOT IS GOOD ENOUGH FOR TINTIN IT’S GOOD ENOUGH FOR ME, BY GOD!!!

Hey Michael, great post – as always!

Are you familiar with Joy Fehr’s article “Female Desire in Prose Poetry”? It’s really interesting because it identifies Fretag’s formula as indicative of the male orgasm – the way it rushes to climax and then falls asleep (I’m paraphrasing) — but then she presents a female plot model that is more circular, that works in the manner of female orgasm, in more of a rolling manner. If you’re interested, I could email you the pdf.

Hey Michael, great post – as always!

Are you familiar with Joy Fehr’s article “Female Desire in Prose Poetry”? It’s really interesting because it identifies Fretag’s formula as indicative of the male orgasm – the way it rushes to climax and then falls asleep (I’m paraphrasing) — but then she presents a female plot model that is more circular, that works in the manner of female orgasm, in more of a rolling manner. If you’re interested, I could email you the pdf.

Hey Michael, great post – as always!

Are you familiar with Joy Fehr’s article “Female Desire in Prose Poetry”? It’s really interesting because it identifies Fretag’s formula as indicative of the male orgasm – the way it rushes to climax and then falls asleep (I’m paraphrasing) — but then she presents a female plot model that is more circular, that works in the manner of female orgasm, in more of a rolling manner. If you’re interested, I could email you the pdf.

Me too, please.

Me too, please.

Me too, please.

Great post, thanks.

Great post, thanks.

Great post, thanks.

(laugh)

Thank you, Kyle. Law school made me worse than I was, humor wise.

(laugh)

Thank you, Kyle. Law school made me worse than I was, humor wise.

(laugh)

Thank you, Kyle. Law school made me worse than I was, humor wise.

That’s who I am.

That’s who I am.

That’s who I am.

Thanks, Christopher. I keep thinking about possible shapes for plots, was remembering all the squiggly line from Tristram Shandy, was trying to imagine what the shape of Mooney would be. Please do send the .pdf.

Thanks, Christopher. I keep thinking about possible shapes for plots, was remembering all the squiggly line from Tristram Shandy, was trying to imagine what the shape of Mooney would be. Please do send the .pdf.

Thanks, Christopher. I keep thinking about possible shapes for plots, was remembering all the squiggly line from Tristram Shandy, was trying to imagine what the shape of Mooney would be. Please do send the .pdf.

Indeed, our ideas about plot and structure do continue to change, collectively. For instance, the 5phase structure to which I refer is merely a creative and logical extension of the classic Greek Tragedy paradigm, and a necessary one I might suggest. All the same dynamics are in play, but consider what would happen if two more ‘phases’ of action were added to the tragedy structure past the point of the denouement. That changes everything. Suddenly the denouement is no longer the end of the story. So what should follow the denouement? In reference to Mr. Baumann’s comment above, it is not a formulaic extension (strictly speaking). It’s not to suggest a story formula as does Joe Campbell. Rather, it is to suggest a question and a logical assumption that answers it. If the tragedy paradigm were extended then what would come after its denouement?

We might consider dias ex machina in that some intervening force comes in to change the conclusion, but we have to ask ourselves, does that really work?

Not really, no, even as dias ex machina was popular with operatic composers in the 18th century. Our ideas and innovations continue to change, collectively, until we find something that works.

For instance, if dias ex machina does not work then that means a ‘4phase’ approach in general might be less than effective. The Greek Tragedy being 3 phases (beginning, middle and end) and then to add the dias ex machina onto it, creating 4phases of storytelling.

As innovated and instigated by Gen. Lew Wallace (circa 1876) what does work is to use 5phases of storytelling, where the fourth phase is something of a mini-Greek-Tragedy, a tragedy in capsule form, if you will, of rising story, peak and falling story which also ends in a denouement, but in a very short span, very condensed. The denouement at the end of this mini-tragedy of phase four PIVOTS the story into the fifth and last phase of the story, which consists of the ‘main event of resolution; and the finale of the story, which is followed by the final conclusion.

Thus, the Greek Tragedy paradigm makes up the first 3 phases of the story. The fourth phase is another tragedy in capsule form, the failure of either an end-game strategy or a counterattack strategy, and the denouement which punctuates this phase serves to PIVOT the story into the final phase.

Here’s a classic example, one of literally thousands. In the novel and film, Harry Potter and the Sorcerer’s Stone, the third phase (the classic Greek Tragedy form) ends with Harry, Ron and Hermeine having survived the Dark Forest to realize that (him who shall not be named) is not dead, but lives in spirit form, and would have killed Harry then and there in the Dark Forest had he the full opportunity to do so. The denouement is that Harry, Ron and Hermeine realize that Dumbledor has been mysteriously called away, and that Snape is going into the ‘secret chamber’ to procure the sorcerer’s stone that very night, which will bring him who cannot be named back into full living form!

Okay…that sucks! They must act! They must take it upon themselves to counter Snape’s attempt to get the stone.

Phase 4 (the counterattack) rises through success in a gauntlet of sorts, and then peaks as they come into a giant chessboard where the destruction of the chess pieces is for real. They must play Wizard’s Chess to gain access to the secret chamber. The falling story ends where Ron sacrifices himself so that Harry can complete the checkmate and enter the secret chamber for the final showdown with Snape. The denouement at the end of this 4th phase is where Hermeine realizes about the value of friendship, even as she knows that Harry must go on alone.

The 5th phase is, in the secret chamber Harry encounters (him who cannot be named) in a final confrontation for possession of the sorcerer’s stone.

Is this genre fiction? Yes, it is.

Does JK Rowling invent this structural form? No, she does not. She is simply aware of its effectiveness.

Structural formats for stories are a study in being effective as a storyteller. The advantage of a 5phase approach is that innovations of the classic Greek Tragedy paradigm are what holds up the ‘great big middle part’ of a novel length story (or a film), and the concluding portions of the story are told in two additional phases, not merely one additional phase, as with dias ex machina.

The basis for the employment of this technique lies in the assumption that the author is building the story toward a finale of conflict resolution. This is typical of genre fiction, where pure literary fiction (as a non-genre) may not be operating on that basic assumption.

Perhaps then a purely literary approach might be where the author is working on the basis of having no structural assumptions at all. One might wonder as to the effectiveness of such an approach while still admitting to the fact that ‘effectiveness’ itself might be one of the assumptions that such an author is seeking to avoid.

In the end result it’s all storytelling, but when we ponder a means of effectiveness on which to build a story to tell then that begins our exploration of plot and structure. To ganer the 5phase approach from successful authors is simply to accept it as a means of being an effective story builder.

Indeed, our ideas about plot and structure do continue to change, collectively. For instance, the 5phase structure to which I refer is merely a creative and logical extension of the classic Greek Tragedy paradigm, and a necessary one I might suggest. All the same dynamics are in play, but consider what would happen if two more ‘phases’ of action were added to the tragedy structure past the point of the denouement. That changes everything. Suddenly the denouement is no longer the end of the story. So what should follow the denouement? In reference to Mr. Baumann’s comment above, it is not a formulaic extension (strictly speaking). It’s not to suggest a story formula as does Joe Campbell. Rather, it is to suggest a question and a logical assumption that answers it. If the tragedy paradigm were extended then what would come after its denouement?

We might consider dias ex machina in that some intervening force comes in to change the conclusion, but we have to ask ourselves, does that really work?

Not really, no, even as dias ex machina was popular with operatic composers in the 18th century. Our ideas and innovations continue to change, collectively, until we find something that works.

For instance, if dias ex machina does not work then that means a ‘4phase’ approach in general might be less than effective. The Greek Tragedy being 3 phases (beginning, middle and end) and then to add the dias ex machina onto it, creating 4phases of storytelling.

As innovated and instigated by Gen. Lew Wallace (circa 1876) what does work is to use 5phases of storytelling, where the fourth phase is something of a mini-Greek-Tragedy, a tragedy in capsule form, if you will, of rising story, peak and falling story which also ends in a denouement, but in a very short span, very condensed. The denouement at the end of this mini-tragedy of phase four PIVOTS the story into the fifth and last phase of the story, which consists of the ‘main event of resolution; and the finale of the story, which is followed by the final conclusion.

Thus, the Greek Tragedy paradigm makes up the first 3 phases of the story. The fourth phase is another tragedy in capsule form, the failure of either an end-game strategy or a counterattack strategy, and the denouement which punctuates this phase serves to PIVOT the story into the final phase.

Here’s a classic example, one of literally thousands. In the novel and film, Harry Potter and the Sorcerer’s Stone, the third phase (the classic Greek Tragedy form) ends with Harry, Ron and Hermeine having survived the Dark Forest to realize that (him who shall not be named) is not dead, but lives in spirit form, and would have killed Harry then and there in the Dark Forest had he the full opportunity to do so. The denouement is that Harry, Ron and Hermeine realize that Dumbledor has been mysteriously called away, and that Snape is going into the ‘secret chamber’ to procure the sorcerer’s stone that very night, which will bring him who cannot be named back into full living form!

Okay…that sucks! They must act! They must take it upon themselves to counter Snape’s attempt to get the stone.

Phase 4 (the counterattack) rises through success in a gauntlet of sorts, and then peaks as they come into a giant chessboard where the destruction of the chess pieces is for real. They must play Wizard’s Chess to gain access to the secret chamber. The falling story ends where Ron sacrifices himself so that Harry can complete the checkmate and enter the secret chamber for the final showdown with Snape. The denouement at the end of this 4th phase is where Hermeine realizes about the value of friendship, even as she knows that Harry must go on alone.

The 5th phase is, in the secret chamber Harry encounters (him who cannot be named) in a final confrontation for possession of the sorcerer’s stone.

Is this genre fiction? Yes, it is.

Does JK Rowling invent this structural form? No, she does not. She is simply aware of its effectiveness.

Structural formats for stories are a study in being effective as a storyteller. The advantage of a 5phase approach is that innovations of the classic Greek Tragedy paradigm are what holds up the ‘great big middle part’ of a novel length story (or a film), and the concluding portions of the story are told in two additional phases, not merely one additional phase, as with dias ex machina.

The basis for the employment of this technique lies in the assumption that the author is building the story toward a finale of conflict resolution. This is typical of genre fiction, where pure literary fiction (as a non-genre) may not be operating on that basic assumption.

Perhaps then a purely literary approach might be where the author is working on the basis of having no structural assumptions at all. One might wonder as to the effectiveness of such an approach while still admitting to the fact that ‘effectiveness’ itself might be one of the assumptions that such an author is seeking to avoid.

In the end result it’s all storytelling, but when we ponder a means of effectiveness on which to build a story to tell then that begins our exploration of plot and structure. To ganer the 5phase approach from successful authors is simply to accept it as a means of being an effective story builder.

Indeed, our ideas about plot and structure do continue to change, collectively. For instance, the 5phase structure to which I refer is merely a creative and logical extension of the classic Greek Tragedy paradigm, and a necessary one I might suggest. All the same dynamics are in play, but consider what would happen if two more ‘phases’ of action were added to the tragedy structure past the point of the denouement. That changes everything. Suddenly the denouement is no longer the end of the story. So what should follow the denouement? In reference to Mr. Baumann’s comment above, it is not a formulaic extension (strictly speaking). It’s not to suggest a story formula as does Joe Campbell. Rather, it is to suggest a question and a logical assumption that answers it. If the tragedy paradigm were extended then what would come after its denouement?

We might consider dias ex machina in that some intervening force comes in to change the conclusion, but we have to ask ourselves, does that really work?

Not really, no, even as dias ex machina was popular with operatic composers in the 18th century. Our ideas and innovations continue to change, collectively, until we find something that works.

For instance, if dias ex machina does not work then that means a ‘4phase’ approach in general might be less than effective. The Greek Tragedy being 3 phases (beginning, middle and end) and then to add the dias ex machina onto it, creating 4phases of storytelling.

As innovated and instigated by Gen. Lew Wallace (circa 1876) what does work is to use 5phases of storytelling, where the fourth phase is something of a mini-Greek-Tragedy, a tragedy in capsule form, if you will, of rising story, peak and falling story which also ends in a denouement, but in a very short span, very condensed. The denouement at the end of this mini-tragedy of phase four PIVOTS the story into the fifth and last phase of the story, which consists of the ‘main event of resolution; and the finale of the story, which is followed by the final conclusion.

Thus, the Greek Tragedy paradigm makes up the first 3 phases of the story. The fourth phase is another tragedy in capsule form, the failure of either an end-game strategy or a counterattack strategy, and the denouement which punctuates this phase serves to PIVOT the story into the final phase.

Here’s a classic example, one of literally thousands. In the novel and film, Harry Potter and the Sorcerer’s Stone, the third phase (the classic Greek Tragedy form) ends with Harry, Ron and Hermeine having survived the Dark Forest to realize that (him who shall not be named) is not dead, but lives in spirit form, and would have killed Harry then and there in the Dark Forest had he the full opportunity to do so. The denouement is that Harry, Ron and Hermeine realize that Dumbledor has been mysteriously called away, and that Snape is going into the ‘secret chamber’ to procure the sorcerer’s stone that very night, which will bring him who cannot be named back into full living form!

Okay…that sucks! They must act! They must take it upon themselves to counter Snape’s attempt to get the stone.

Phase 4 (the counterattack) rises through success in a gauntlet of sorts, and then peaks as they come into a giant chessboard where the destruction of the chess pieces is for real. They must play Wizard’s Chess to gain access to the secret chamber. The falling story ends where Ron sacrifices himself so that Harry can complete the checkmate and enter the secret chamber for the final showdown with Snape. The denouement at the end of this 4th phase is where Hermeine realizes about the value of friendship, even as she knows that Harry must go on alone.

The 5th phase is, in the secret chamber Harry encounters (him who cannot be named) in a final confrontation for possession of the sorcerer’s stone.

Is this genre fiction? Yes, it is.

Does JK Rowling invent this structural form? No, she does not. She is simply aware of its effectiveness.

Structural formats for stories are a study in being effective as a storyteller. The advantage of a 5phase approach is that innovations of the classic Greek Tragedy paradigm are what holds up the ‘great big middle part’ of a novel length story (or a film), and the concluding portions of the story are told in two additional phases, not merely one additional phase, as with dias ex machina.

The basis for the employment of this technique lies in the assumption that the author is building the story toward a finale of conflict resolution. This is typical of genre fiction, where pure literary fiction (as a non-genre) may not be operating on that basic assumption.

Perhaps then a purely literary approach might be where the author is working on the basis of having no structural assumptions at all. One might wonder as to the effectiveness of such an approach while still admitting to the fact that ‘effectiveness’ itself might be one of the assumptions that such an author is seeking to avoid.

In the end result it’s all storytelling, but when we ponder a means of effectiveness on which to build a story to tell then that begins our exploration of plot and structure. To ganer the 5phase approach from successful authors is simply to accept it as a means of being an effective story builder.

man, this is good. I need to sit w/ this for a while. so many perspectives…

coming from a poetry background, it took me a long time to get comfortable w/ plot. john hawkes also fucked me up w/ his notions of a novel w/out characters, plot, theme, etc., and I still think I’m like the classic russians: I start w/ an idea I want to explore and let plot and characters develop around that.

one of those vonnegut quotes has been taped to my monitor for years, as is its capsule version: ACTION = character.

I’ve been thinking a lot lately about the narrative arc (those diagrams) and that start-near-the-end concept. but then, how much exposition/background is needed for clarity before jumping onto the high tension wires? still thinking on that… (and I like moving around in time… ya know, past-present-future existing always in the now… so flashback, so-called, can’t be avoided, can it?)

thanks again, michael. this may be the juiciest one yet.

man, this is good. I need to sit w/ this for a while. so many perspectives…

coming from a poetry background, it took me a long time to get comfortable w/ plot. john hawkes also fucked me up w/ his notions of a novel w/out characters, plot, theme, etc., and I still think I’m like the classic russians: I start w/ an idea I want to explore and let plot and characters develop around that.

one of those vonnegut quotes has been taped to my monitor for years, as is its capsule version: ACTION = character.

I’ve been thinking a lot lately about the narrative arc (those diagrams) and that start-near-the-end concept. but then, how much exposition/background is needed for clarity before jumping onto the high tension wires? still thinking on that… (and I like moving around in time… ya know, past-present-future existing always in the now… so flashback, so-called, can’t be avoided, can it?)

thanks again, michael. this may be the juiciest one yet.

man, this is good. I need to sit w/ this for a while. so many perspectives…

coming from a poetry background, it took me a long time to get comfortable w/ plot. john hawkes also fucked me up w/ his notions of a novel w/out characters, plot, theme, etc., and I still think I’m like the classic russians: I start w/ an idea I want to explore and let plot and characters develop around that.

one of those vonnegut quotes has been taped to my monitor for years, as is its capsule version: ACTION = character.

I’ve been thinking a lot lately about the narrative arc (those diagrams) and that start-near-the-end concept. but then, how much exposition/background is needed for clarity before jumping onto the high tension wires? still thinking on that… (and I like moving around in time… ya know, past-present-future existing always in the now… so flashback, so-called, can’t be avoided, can it?)

thanks again, michael. this may be the juiciest one yet.

Your example is from Harry Potter. Your two other phases are really just part of the rising action.

Your example is from Harry Potter. Your two other phases are really just part of the rising action.

Your example is from Harry Potter. Your two other phases are really just part of the rising action.

[…] been revisiting Michael Kimball’s craft note on plotting because I’m stuck on some work. I appreciate how he summarizes the variety of driving forces […]

[…] Guest Lecture #4: Story and Plot […]