Reading Frank Miller’s influences on Christopher Nolan’s Dark Knight Trilogy

One more post on the Batman, if you’ll please. It’s no secret that Christopher Nolan’s Dark Knight Trilogy drew a lot of inspiration from Frank Miller—specifically, from his 1986 mini-series Batman: The Dark Knight Returns and its 1987 follow-up, Year One (which featured art by David Mazzucchelli). And so I felt like taking some time to note all the connections (or at least the ones I can see—feel free to chime in as to what I’ve missed!).

I’ve already commented elsewhere on how Batman Begins took:

- the Tumbler design (The Dark Knight Returns);

- Batman’s escape from the police by means of a bat homing device (Year One);

- and the ending in which Commissioner Gordon muses about the arrival of the Joker, having received one of his calling cards (Year One).

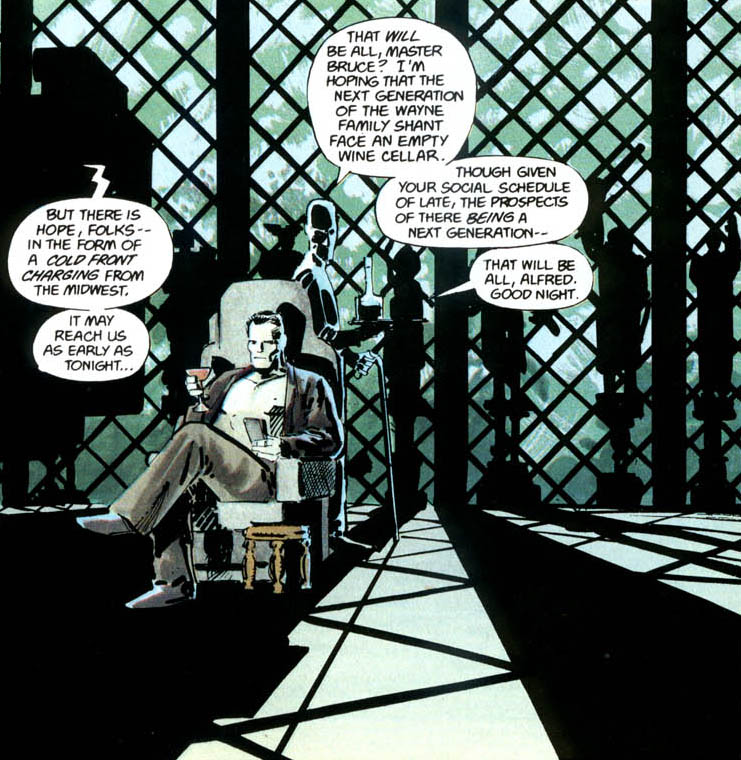

And there are still more connections. Commissioner Gordon’s character arc in that film is similar to the one he follows in Year One—he even has a corrupt partner named Flass. Furthermore, Bruce Wayne distances himself from the Batman by cultivating the image of a drunken playboy:

That’s everything that I can see in the first film.

The Dark Knight is I think the least indebted to Miller of the three films. Nonetheless, its ending, wherein Two-Face kidnaps Gordon’s family, echoes the mob’s kidnapping of Gordon’s family at the conclusion of Year One—Batman even saves Gordon’s son from falling:

Moving on to the The Dark Knight Rises …

There are numerous connections.

1. We open with Bruce Wayne retired from being Batman. Roughly the same amount of time has passed. (In The Dark Knight Rises, it’s been eight years; in The Dark Knight Returns, ten.)

2. Alfred spends time berating his master, expressing the wish that he settle down.

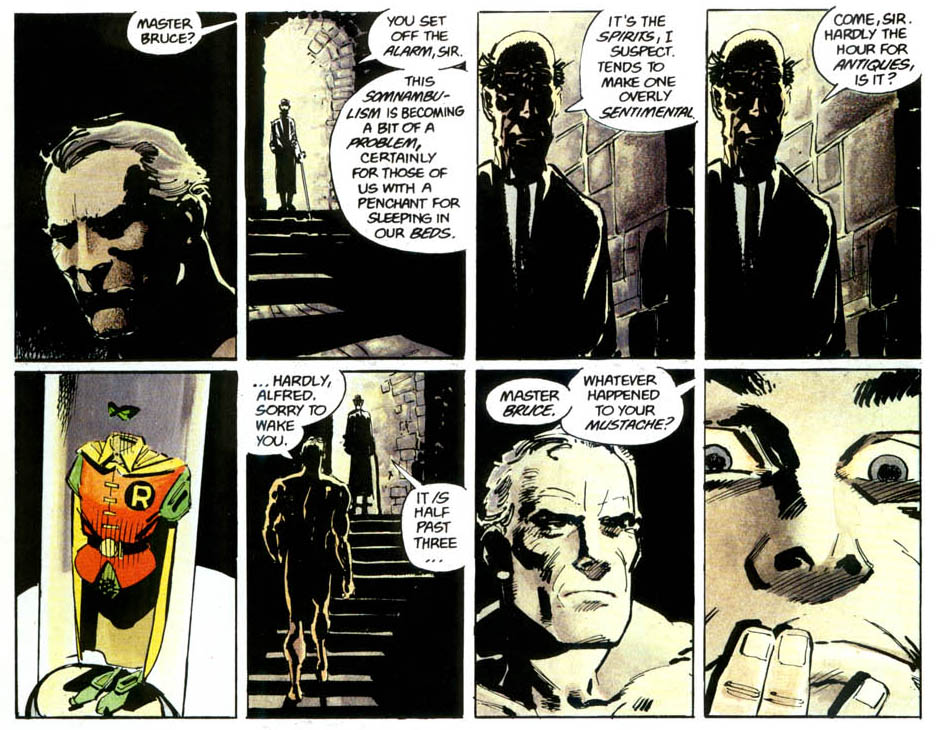

3. Alfred later finds Bruce Wayne in the Batcave, now clean-shaven.

(In Rises, Bruce Wayne shaves off a full beard, as opposed to just a mustache in Returns, but this Batcave scene is still the one where he’s done it.)

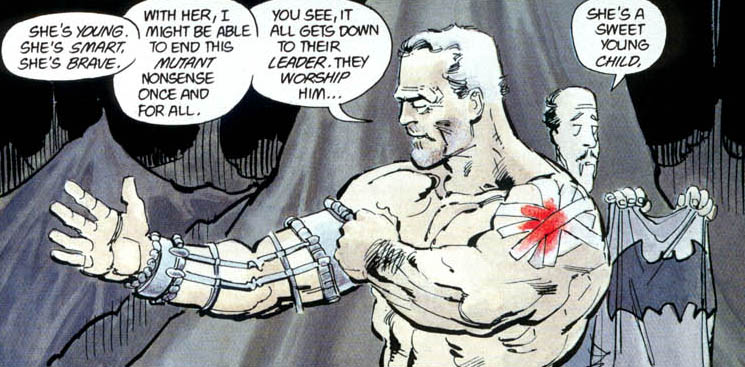

4. In order to return to being Batman, Bruce Wayne has to stick a limb in a mechanical brace. In Rises, it’s his leg; in Returns, it’s his arm:

5. Mathew Modine’s character, Deputy Commissioner Foley, is very reminiscent of Captain/Commissioner Ellen Yindel. He spends the first half of the film wanting to catch Batman, even pulling cops from their pursuit of Bane. But he later allies himself with Batman. (That said, the film does this quite differently than in Returns, mainly due to its inclusion of material drawn from Knightfall and No Man’s Land.)

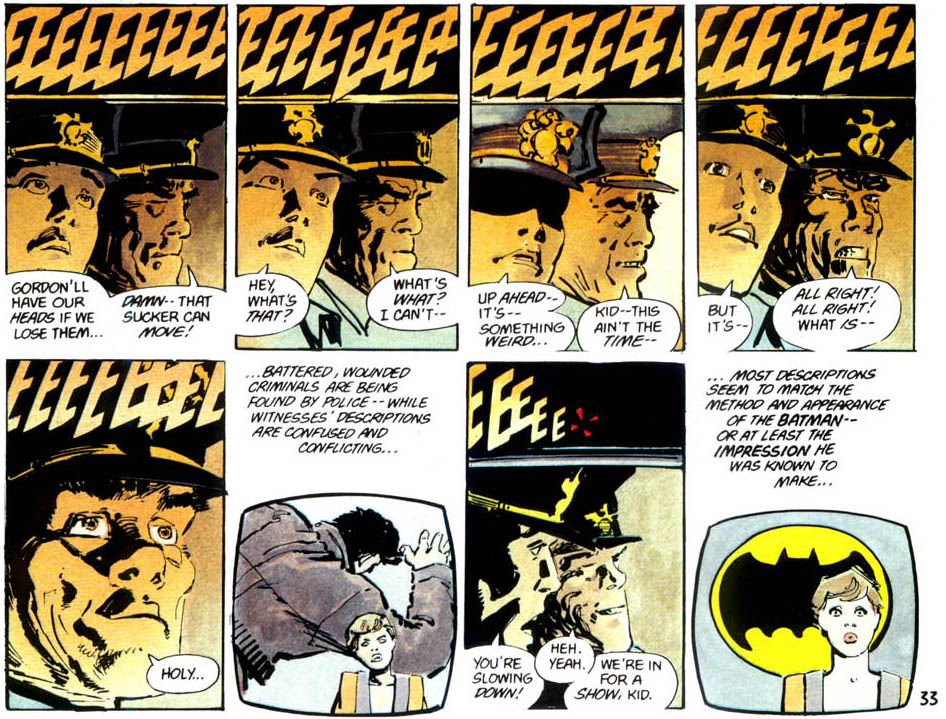

6. When Batman reappears, chasing Bane, two cops see him. The older cop says to the younger one, “Oh, boy, you are in for a show tonight, son!”

And just like in the comic, the younger one tries to apprehend Batman (he draws a gun on him and accidentally shoots him). Batman basically ignores him.

7. Bane is in some ways more like the Mutant Leader than he is like Bane, lacking his Venom drug, and instead being more concerned with creating an alternate army that rules Gotham. (There’s even that odd line where Bane taunts Batman for fighting “like a younger man, nothing held back—admirable, but mistaken”—which perhaps hailed from the Mutant Leader’s many comments about Batman’s age? I’m really speculating here, though.)

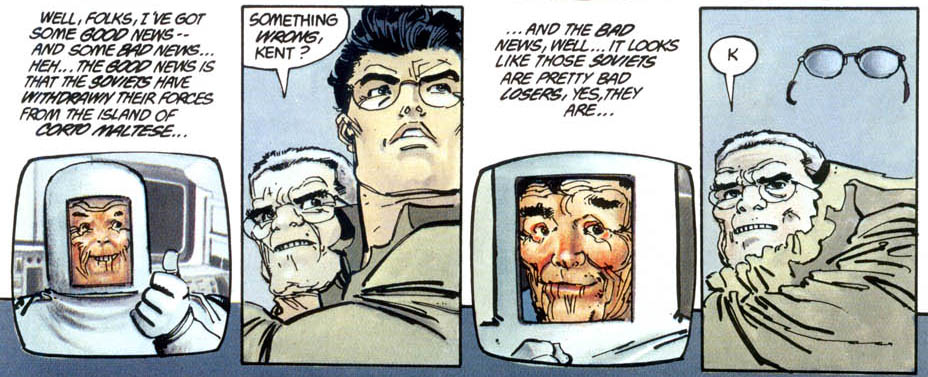

8. A nuclear threat hangs over Gotham. (Although in Returns, the bomb actually does some real damage to Gotham.)

9. Both the film and the comic are TDKR (and yes, it does annoy me a little that when I use that initialism now, Google thinks I’m referring to the film).

10. Finally, the Selina Kyle we see in Rises takes a lot from Miller’s portrayal of her in Year One (even down to her sidekick Jen, who’s based on Holly):

Now, I’m not criticizing Nolan for stealing from Miller—not at all! (It’s too bad, however, that Miller never gets so much as a thank you. I assume that’s a legal issue? But still!) I believe strongly that art proceeds by derivation, and I also think originality overrated. And I adore Miller’s Batman comics, and think that if you’re going to steal—steal from the best. (Indeed, one of the things I like best about The Dark Knight Rises is how it merges so many different Batman storylines; Batman Begins does something similar, with Year One and The Long Halloween).

But that said. I do think that Nolan has missed a substantial element that made Miller’s versions of the Dark Knight so brilliant—and that is the argument that Batman is a psychopath. And a criminal, to boot. He’s not a nice guy! He isn’t a person that you can be friends with!

In Nolan’s version, Batman is very noble. He takes the rap for Harvey Dent. He seems driven by the purest intentions: to save Gotham (like his father tried to, through philanthropy). But Miller’s Batman is obsessed with fighting crime, to the point of myopia, mainly enjoys beating the shit out of criminals.

What’s more, in Nolan, Batman is pursued by cops because he’s been unjustly framed. But in Miller, Batman’s pursued by criminals because his actions are illegal! (They’re illegal, too, in Nolan, but no one says a word about that there.)

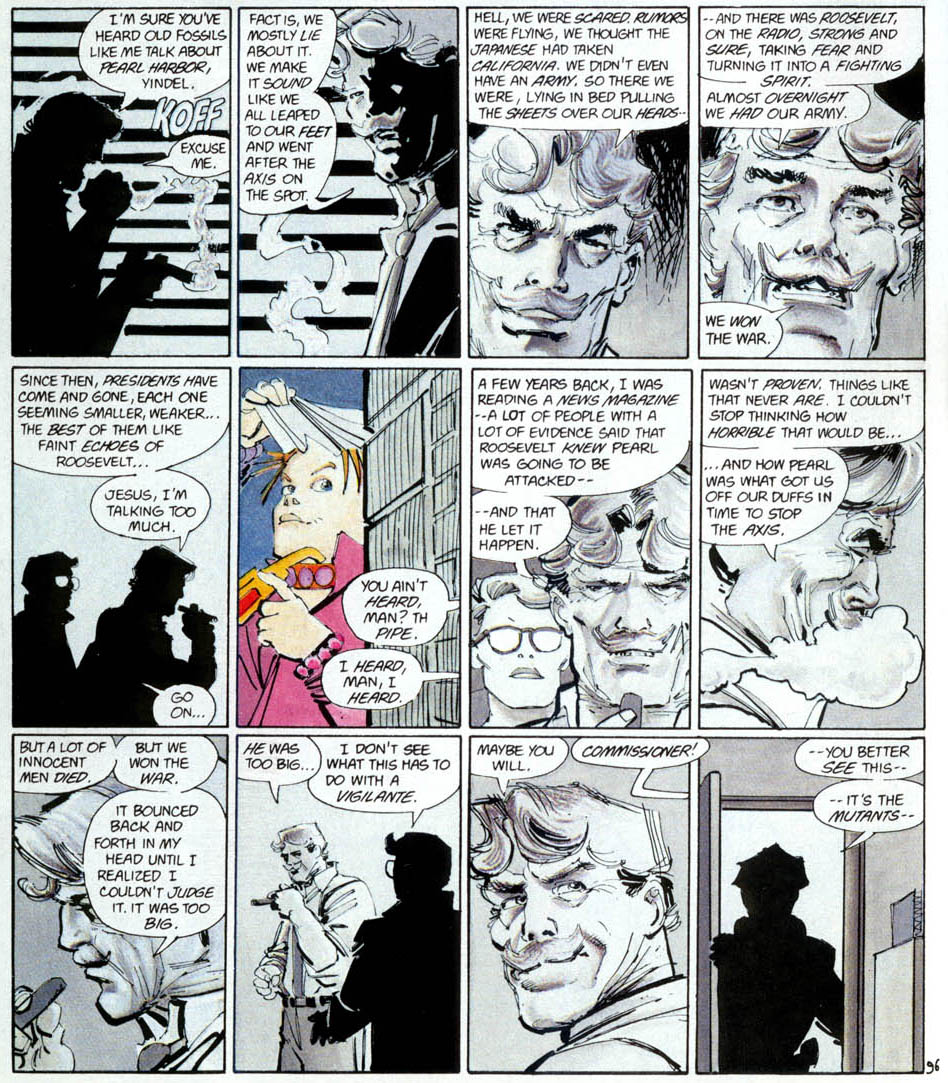

In Miller’s version, the cops are perfectly correct to pursue Batman—he’s committed any number of serious crimes. But Miller uses this opportunity to actually ask whether laws ultimately serve justice. He wants to know whether we should have forces outside the law. Gordon argues precisely in favor of that to Yindel:

And Yindel eventually comes to agree with him:

In other words, Miller out and out acknowledges that Batman is a fascist fantasy, and requires us to recognize that point in order to enjoy his story. Indeed, he claims that that is precisely what we enjoy when we enjoy Batman. He compares Batman to Nietzsche’s concept of the Übermensch:

I think that in order for [Batman] to work, he has to be a force that in certain ways is beyond good and evil. It can’t be judged by the terms we would use to describe something a man would do because we can’t think of him as a man. […] [I]t’s very clear to me that our society is committing suicide by lack of a force like that. A lack of being able to deal with the problems that are making everything we’ve got crumble to pieces. As far as being fascist, my feeling is … only if he assumed political office. [Laughter.] If there were a bunch of these guys running around and beating up criminals, we’d have a serious problem. (Kim Thompson, “Interview Two,” Frank Miller: The Interviews, page 34)

In the end, Miller has the courage of his convictions, while Nolan wants it numerous ways: Batman as vigilante, Batman as super-cop, Batman as a friend to school children, Batman as a collectible toy. At the end of the day, Nolan’s Batman is the one who has to appeal to every demographic—and falls far short of the vision Miller argued for 26 years ago in his comics.

OK, that’s enough Batman for now, I think. My next few posts will cast about for something else to talk about. (Although is there even anything besides superheroes? I no longer remember.)

Until then, have fun pretending you’re a fascist.

Tags: Batman, Batman Begins, Batman: Year One, Christopher Nolan, David Mazzucchelli, Frank Miller, Friedrich Nietzsche, The Dark Knight, The Dark Knight Returns, The Dark Knight Rises

Really enjoyed this article. I think Nolan has gone on record as saying that Year One (Miller) and the Long Halloween(although not by Miller) influenced Begins and The Dark Knight. And although it is not written by Miller, the recent editions of the Long Halloween collection come with a preface written by Nolan(?!?). So I feel he has acknowledged some debts to comic writers.

I think most avid Batman comic book readers and legit Batman fans acknowledge Batman as being a total psychopath. And yes, this definitely is lacking in Nolan’s version of him (outside of some acknowledgements between Batman and the Joker in the Dark Knight). However, I’m not sure if I can think of Batman as the ubermensch. I tend to think of him more as Sisyphus. At the heart of Batman is his golden rule: That he should not kill (ok, let’s not get into the arguments over the un-developed 1940’s gun toting Batman or the accidental deaths, “not saving”, etc. etc.), no matter how psychotic he is. He therefore sets up a never-ending Sisyphus-esque journey of constantly catching the “bad guys”, placing them in Arkham, and them constantly escaping, with many of them ( especially the Joker) escaping and existing for the pure reason to interact with Batman. And if Batman has no one left to interact with? Batman is desperately trying to do what he thinks is right and for the good of Gotham city, all because he cannot get over his parent’s deaths, and in the end is arguably failing and creating a never ending cycle that can be argued is ultimately damaging to Gotham.

More on Miller’s version of Batman as a complete psychopath (Batman’s relationship with Robin as depicted in All Star Batman and Robin): http://i1.kym-cdn.com/entries/icons/original/000/000/234/GoddamnBatman.jpg

Thanks!

(And I’m one of the few who enjoys Miller’s All Star Batman and Robin.)

All Star Batman and Robin is also great because it shows how Miller is nearly a psychopath himself.

In short then, the dilemma of Nolan’s Bat-work is that insisting on the realism of Batman’s world means sidestepping the uncomfortable fact that in the real world Batman would be a fascist character.

Incidentally, the first part of the animated adaptation of TDKR will be released later this month (http://www.worldsfinestonline.com/2012/09/05/new-video-clips-images-from-animated-batman-the-dark-knight-returns-part-one/). Unfortunately, the style has the same over-creamy look as that of the animated Year One, and misses the caffeinated, punkish line-work of the original. I much prefer the style used for the brief TDKR adaptation in the BTAS episode “Legends of the Dark Knight” (http://www.worldsfinestonline.com/WF/batman/tnba/episodes/19legendsdarkknight/).

With regards to Batman, my feeling is that while Nolan’s films get all the attention, it’s the animated shows and their direct-to-video spin-offs that will survive best. “Mask of the Phantasm” was a better look at Batman’s origins than Batman Begins, and the flashback scene from the uncut version of “Batman Beyond: Return of the Joker” made every Joker-scene in The Dark Knight look feeble. What is more, the animated shows did not make the mistake of insisting on utter realism; they took place in an exquisitely stylized world where Batman made sense, thus sidestepping the fascist dilemma of Nolan’s psudo-reality.

That definitely is a problem. And I could see Nolan finding some other solution to it…but it seems to me instead that he took various things from Miller, but missed Miller’s deeper interrogation of the character.

My friends keep telling me I need to watch the animated series. I intend to get around to them soon.

I think you’re exactly right about the thoroughness of Nolan’s compromises.

Can’t tell whether he has a questionably humanized crime-lord because he doesn’t want to get involved in the infinite nuance of a law-breaking law-sustainer — a guardian not who guards himself with more or less success (Plato, and us), but rather, whose guardianship depends for effectiveness on acting outside the ‘territory’ he guards.

–or whether this paradox is militated absolutely against by commercial anticipations.

You could make a movie where a violent problem-solver stops thugs from being too illegal – who did shoot Liberty Valance? – , but, I guess, not when you spend the kind of money that requires (or at least expects getting) a ~$400 million (?) gate.

And who cares whether the failure is Nolan’s personally or the business’s institutionally: the entertainment many people get from the spectacle of the movies is diminished – among craft diminutions! – by their embrace of character cheating.

By the way, it’s an old quibble, but:

That’s sharp; in the sense that “fascism” means ‘non-hereditary totalitarian’, Miller’s Batman doesn’t seem to be political-economically a “fascist” to me. Maybe either a ‘sadist’ or a ‘sociopath’ or ‘uncontrollably urgent’, but a goosestepper among a million? or a calmly smug reviewer of a parade of a million goosesteppers?

I generally don’t like to compare works from two different mediums, but I think Nolan was under more duress to appeal to a far more massive audience—so he doesn’t have the freedom to be as creative with the batman character as Miller did.

You want people to sympathize with your hero? You have to make him somewhat noble. But people like flaws so you give him those as well, which is what Nolan did.

I don’t know for sure, but I have a hunch that Dark Knight Returns is a better graphic novel than Dark Knight Rises is a movie.

Returns was good, but I didn’t like it as much as The Long Halloween or Knightfall. Hell I liked the Killing Joke better than Returns. I read a bunch of these comics to prep for the movie. Never was into comics as a kid.

But yeah…in a lot of ways Rises was basically Dark Knight Returns with Bane and his mob instead of the mutants and their leader.

Bane was a bad-ass villain in Dark Knight Rises, but not close to as incredible as he is in the comics. Not even the same character, really.

[…] Reading Frank Miller’s Influences on Christopher Nolan’s Dark Knight Trilogy […]

Really great article! I just wanted to add a note: the “fighting like a younger man” quote from Bane actually comes straight from what Batman thinks about himself during the fight with the Mutant leader in The Dark Knight Returns.

I actually think that – by saying that Chris Nolan didn’t have as much creative freedom as Miller did – you give Nolan more credit than he really deserves.

I think it has less to do with his duty to speak to a wider demographic rather than the general fact that Nolan has no real clue what to make of the Batman character. He seems generally confused with what to make of him which might first and foremost stem from the problem that Christopher Nolan lacks a true knowledge and understanding of human psychology in general.

Nolan tried incredibly hard to make Batman a flawed hero, but he didn’t really seem to have a grasp on what makes a human being flawed. Batman’s religious, moral, political and sexual ideals are all over the place in Nolan’s films. Thus his very confused character. In the hands of a better director (and writer), this confusion in how to characterise him could have lead to a completely new (and fascinating) identity of its own. In Nolan’s hands – however – it just seems very sloppy and not at all thought through.

Don’t forget that Tim Burton had very little freedom in how to express his creative ideals with his very first Batman film, too. Yet he was more than willing enough to paint a very diverse – if not necessarily sympathetic – picture of Batman. Which still stood true in it’s follow-up, Batman Returns, which – obviously – gave him a lot more freedom.

“He seems generally confused with what to make of him which might first

and foremost stem from the problem that Christopher Nolan lacks a true

knowledge and understanding of human psychology in general.”

How would you have any idea if Nolan lacks understanding of human psychology? He has put out many films and many people have felt enriched from his character studies, so clearly his work resonates with large groups.

And then when you end your comment by praising Burton’s movies over Nolan’s—I’m sorry but that sounds ridiculous. I think it is generally acknowledged that Nolan’s batman movies are the best version of Batman portrayed so far on screen. Sure there is a niche that prefers Burton’s Batman work—but how you can give those movies as an example of why Nolan fails with his movies is beyond me.

Neither did I praise Burtons Batman movies over Nolans, nor did I say that Burtons Batman is a superior portrayal of the character over Nolans (Even though I think it is. But that’s merely my opinion and has nothing to do with the discussion whatsoever.). I was merely stating what I though to believe was the obvious: that Burtons was characterwise better fleshed out in terms of psychology and therefore trying to refute your claim that – in Nolan’s case – the lack of a real character was due to his commitment to speak to a wider demographic. I’m also not saying that Burton’s Batman is the more complex character (Although my opinion on that may or may not vary), just that he has a more distinct personality and a distinct character of his own.

It is also widely accepted (especially after Rises) that Nolan’s films might be high on (overtly) psycho-analysing but very little on real human psychology to boost it. Stating “I’m angry!” is not an indication of anger management issues. As is a kiss that comes out of nowhere and casual sex not a sign for feelings of love and commitment towards another person. Nolan’s films are definitely “not” character analysis. And that many people like those films is not a prove to the contrary.

Please forgive me if I’m too thin-skinned but your comment comes off as being written rather angrily. Seeing how you completely misread and misinterpreted a lot of what I was saying. I didn’t mean to offend you if that was the case and I feel sorry if I did. I just wanted to contribute to a discussion. I’m sorry if it came off as rude on my part. I really didn’t mean to.

My comment actually was sort of angry, or frustrated. I’m just blunt online. It’s nothing personal. Sorry about that!

But I do feel like you backtracked on your comment about which are the better Batman movies. Whether it was intended or not—I gathered that you favored the Burton films. It was fairly obvious, so that’s why I argued in that vein.

Yeah I can see why Nolan’s movies don’t seem like character studies. I’ve certainly seen better character studies in movies.

[…] “Reading Frank Miller’s influences on Christopher Nolan’s Dark Knight Trilogy” (HTMLGIANT) […]

[…] the same year Alan Moore and Dave Gibbons unleashed Watchmen, was extraordinarily influential; here’s a fine piece about its impact on Chris Nolan’s trilogy, for starters. And this cover sums up the tone of the tome: Of the four issues, it’s the only […]

[…] Reading Frank Miller’s influences on Christopher Nolan’s Dark Knight Trilogy […]

[…] may not resemble Adam West or Michael Keaton or anything artists Frank Miller or Neal Adams might render, but so […]

[…] may not resemble Adam West or Michael Keaton or anything artists Frank Miller or Neal Adams might render, but so […]

[…] may not resemble Adam West or Michael Keaton or anything artists Frank Miller or Neal Adams might render, but so […]