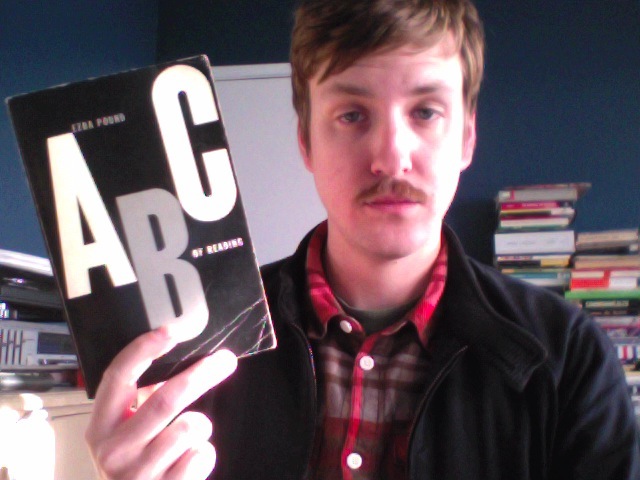

Excerpts

“Literature is language charged with meaning.”

From ABC of Reading

by Ezra Pound

Chapter Four

1

‘Great literature is simply language charged with meaning to the utmost possible degree.’

Dichten = condensare.

I begin with poetry because it is the most concentrated form of verbal expression. Basil Bunting, fumbling about with a German-Italian dictionary, found that this idea of poetry as concentration is as old almost as the German language. ‘Dichten’ is the German verb corresponding to the noun ‘Dichtung’ meaning poetry, and the lexicographer has rendered it by the Italian verb meaning ‘to condense’.

The charging of language is done in three principle ways: You receive the language as your race has left it, the words have meanings which have ‘grown into the race’s skin’; the Germans say ‘wie einem der Schnabel gewachsen ist’, as his beak grows. And the good writer chooses his words for their ‘meaning’, but that meaning is not a set, cut-off thing like the move of knight or pawn on a chess-board. It comes up with roots, with associations, with how and where the word is familiarly used, or where it has been used brilliantly or memorably.

You can hardly say ‘incarnadine’ without one or more of your auditors thinking of a particular line of verse.

Numerals and words referring to human inventions have hard, cut-off meanings. That is, meanings which are more obtrusive than a word’s ‘associations’.

Bicycle now has a cut-off meaning.

But tandem, or ‘bicycle built for two’, will probably throw the image of a past decade upon the reader’s mental screen.

There is no end to the number of qualities which some people can associate with a given word or kind of word, and most of these vary with the individual.

You have to go almost exclusively to Dante’s criticism to find a set of OBJECTIVE categories for words. Dante called words ‘buttered’ and ‘shaggy’ because of the different NOISES the make. Or pexa et hirsuta, combed and unkempt.

He also divided them by their different associations.

NEVERTHELESS you still charge words with meaning mainly in three ways, called phanopoeia, melopoeia, logopoeia. You use a word to throw a visual image on to the reader’s imagination, or you charge it by sound, or you use groups of words to do this.

Thirdly, you take the greater risk of using the word in some special relation to ‘usage’, that is, to the kind of context in which the reader expects, or is accustomed, to find it.

This is the last means to develop, it can only be used by the sophisticated.

(If you want really to understand what I am talking about, you will have to read, ultimately, Propertius and Jules Laforgue.)

IF YOU WERE STUDYING CHEMISTRY you would be told that there are a certain number of elements, a certain number of more usual chemicals, chemicals most in use, or easiest to find. And for the sake of clarity in your experiments you would probably be given these substances ‘pure’ or as pure as you could conveniently get them.

IF YOU WERE A CONTEMPORARY book-keeper you would probably use the loose-leaf system, by which business houses separate archives from facts that are in use, or that are likely to be frequently needed for reference.

Similar conveniences are possible in the study of literature.

Any amateur of painting knows that modern galleries lay great stress on ‘good hanging’, that is, of putting important pictures where they can be well seen, and where the eye will not be confused, or the feet wearied by searching for the masterpiece on a vast expanse of wall cumbered with rubbish.

At this point I can’t very well avoid printing a set of categories that considerably antedate my own How to Read.

2

When you start searching for ‘pure elements’ in literature you will find that literature has been created by the following classes of persons:

1

Inventors. Men who found a new process, or whose extant work gives us the first known example of a process.

2

The masters. Men who combined a number of such processes, and who used them as well as or better than the inventors.

3

The diluters. Men who came after the first two kinds of writer, and couldn’t do the job quite as well.

4

Good writers without salient qualities. Men who are fortunate enough to be born when the literature of a given country is in good working order, or when some particular branch of writing is ‘healthy’. For example, men who wrote sonnets in Dante’s time, men who wrote short lyrics in Shakespeare’s time or for several decades thereafter, or who wrote French novels and stories after Flaubert had shown them how.

5

Writers of belles-lettres. That is, men who didn’t really invent anything, but who specialized in some particular part of writing, who couldn’t be considered as ‘great men’ or as authors who were trying to give a complete presentation of life, or of their epoch.

6

The starters of crazes.

Until the reader knows the first two categories he will never be able ‘to see the wood for the trees’. He may know what he ‘likes’. He may be a ‘compleat book-lover’, with a large library of beautifully printed books, bound in the most luxurious bindings, but he will never be able to sort out what he knows to estimate the value of one book in relation to others, and he will be more confused and even less able to make up his mind about a book where a new author is ‘breaking with convention’ than to form an opinion about a book eighty or a hundred years old.

He will never understand why a specialist is annoyed with him for trotting out a second- or third-hand opinion about the merits of his favourite bad writer.

Until you have made your own survey and your own closer inspection you might at least beware and avoid accepting opinions.

1

From men who haven’t themselves produced notable work.

2

From men who have not themselves taken the risk of printing the results of their own personal inspection and survey, even if they are seriously making one.

'this book is pretty tight or whatever, the sun is so bright yesterday, i miss it more than most but maybe not'

Tags: ezra pound, litblogging wis frvr, poetry, reading

“literature is news that stays news”

seems like it’d be an interesting read. not directly related, but i really want to read The Great American Novel by William Carlos Williams

seems like it’d be an interesting read. not directly related, but i really want to read The Great American Novel by William Carlos Williams

i posted on that a bit back, it’s in his collection called IMAGINATIONS which i got at adobe for $10 i think, there’s a lot of other stuff so i think it’s better than the little book on its own

i like this book, but i always felt that the “to the utmost possible degree” part was stupid.

i also remember being terrified when i first read the six classes of writers years ago. i kept reading and rereading that part, searching my life for whatever horrifying signs i could construct. now i find it really amusing.

thanks for posting, looking at my copy now.

ABCs of Reading, a book I bought second-hand at Moe’s Bookstore on Telegraph Avenue in Berkeley a LONG time ago. And I still have the book. It is one of those that did not become a relic from my teenagehood. Rather, I have grown to it. As I mature as a writer and a woman, I am able to read the book as a document to accompany my writing journey, like an old comrade, a peer, finally.

Well, emphasizing the admission of “degree” of charging language with “meaning” is probably just a way of trying to pick out “great literature” from all literature.

I wonder if ‘to charge with meaning’ isn’t itself otiose (in the case of language usage in general). A red octagon with a white STOP inside it is probably as ‘charged’ as any -seme could be for the narrow purpose of making driving (relatively) safe by a specific means. Is this traffic sign the most literary image possible for that purpose there – a ‘greatly literary’ image – ? – being “charged with meaning”, is a ‘stop’ sign “literature” at all?

That is, is every piece of language usage “literature”? – or is there a minimum amount of “charge”, but higher (and/or otherwise different) than bare utility, for a piece of language usage to be “literature”?

Ought “literature” to be reserved for a more specific kind of action or engagement than being “charged with meaning”?

i agree. i think. otiose is a good word. yes, i’m having the same problem with the phrase, just from a different perspective. what does “utmost possible degree” mean, exactly? how many degrees are there? how will i know when i find language that is charged utmostly? rather than only mostly.

also, like you say, is there a minimum amount of charge? what is “charged”? like you say, STOP in a big red sign is pretty charged, but this can’t be what he’s after. i’m thinking charged could almost be thought of as “layered,” a many-meaning-charge or somesuch. from reading a bit further in this opening part, it seems he’s after language which is charged with “multiple” meanings.

yet he doesn’t say that. now i really have to reread this.

okay, so he says you charge a word in three ways: “called phanopoeia, melopoeia, logopoeia. You use a word to throw a visual image on to the reader’s imagination, or you charge it by sound, or you use groups of words to do this.”

the “this” in that last sentence is unclear to me. still, how does a thing become utmostly charged? by using these three elements completely?

also, would it be wrong to think of his ideas of charge and meaning and literature as somehow part of new criticism’s way of seeing?

i really didn’t mean to ask so many questions. i have to eat udon now.

How do you get the excerpt to look that way, like a floating page?

fuck i gotta hit up adobe.

text

do people make literature surveys anymore? i don’t write in the margins or even take notes.

so actually he quotes himself from how to read, in chapter two he cites this same quotation after stating the ‘new’ simplified version, written years after the other: ‘literature is language charge with meaning’ at some point he says his sensibilities have changed as he’s gotten older, i dunno

i think his idea of meaning is just those three ways, like you said, in which it can be ‘charged’: image & sound, basically

that and reading (being familiar with a lot), avoiding cliches: i feel that is most of his advice

i think obviously he has some antiquated views but it was 1934 after all, for instance he also seems to be pretty into social darwinism but it doesn’t really matter

i think what he’s talking about is sort of like what i imagine the glass bead game to be like

i totally wrote about this more than ten days ago

http://42stories.wordpress.com/2011/02/11/the-abc-of-reading/

but yours is much better. way to be

nice

&thanx

Reminds me of what Picasso told me: how Picasso, Max Jacob and Apollinaire, when they were young, would run through Montmartre, dashing down the steps, and shouting “Long live Rimbaud! Down with Laforgue!”

vipstores.net

The excerpts retrieved at Abigwind’s link below include the claims a) that effective writing succeeds at ‘teaching, moving, or delighting’; and b) that what discloses unsuccessful writing is words that don’t function or that distract from the pith or gist they pretend to constitute or enshell. These insights seem to me adequately engineered to leap from their historical context to most any other.

(Cliche – decadent expectation, or rather, perception decayed by expectation – is surely a mark of dysfunction, though that doesn’t mean that artful cliche can’t itself be a means of ‘making new’.)

To me, much of Pound’s criticism – theses and practical adventures – is not only not “antiquated”, but is indefatigable. His cruel, idiotic racism can’t be ‘forgiven’, but the virtues of his poetry and his mind are as worthy of reckoning as those of the greatest poets.

If you haven’t given it a shot yet, try Kenner’s The Pound Era.

will definitely check out The Pound Era. one of my favorite books is by Kenner, called A Homemade World: The American Modernist Writers. it’s really a must for anyone interested in writers from that time period. he writes about the american modernists and their art as if he’s lived their life with them and watched them make. the greatest thing about that book is that it itself is a work of art.

will definitely check out The Pound Era. one of my favorite books is by Kenner, called A Homemade World: The American Modernist Writers. it’s really a must for anyone interested in writers from that time period. he writes about the american modernists and their art as if he’s lived their life with them and watched them make. the greatest thing about that book is that it itself is a work of art.

If you are a writer and a reader of some sort, and I take it simply because you’re here that you are, I don’t think what he means by ‘charge’ or ‘utmost degree’ can really be that alien to you. In as much as you aren’t just giving the old man a hard time (and this isn’t to suggest you are in some way wrong for testing his assumptions), I would try and answer your questions in two ways: 1.) By pointing out that Pound is merely pseudo-systemizing what writers have known and been saying for centuries (the famous Keats line to Shelley is a simple approximation: load every rift with ore), and 2.) by also pointing out that his pseudo-system isn’t too far from the reality: meaning is that in the text which the reader responds to, or can respond to, and meaning is achieved in the contexts formed out of words and their sounds working in conjunction; in as much as the writer’s goal is to make meaning available to a reader, it is best to make as much meaning available as possible.

I think he is probably using the word ‘charge’ in the then-newer sense of an ‘electrical charge’, but also in the now more muted sense of charging a messenger with a message, of bestowing intent and purpose upon the conveyor by means of your conveyance, and there are several other senses of the word he may or may not be calling into his contextual matrix. If ‘utmost degree’ feels like an unearned trope (as you pointed out: which freaking degrees, Ezra?), and it may well be that he failed to fully take advantage of meanings, there, I don’t think it’s too terribly out of place in the pseudo-system. He is, I think, simply indicating that you should make your meanings many-sided.

Which I don’t think is necessarily a ‘New Critical’ doctrine; in fact, much of New Criticism is concerned with the shaving away of meaning; meanings which are seen as ‘misleading’ or ‘distracting’, or even just those which you don’t happen to like, from my understanding of it.

yes, avoiding cliches. i can see that, when he talks about “usage.” cool.

even if i were being hard on the old guy, he could take it. but i’m not. and these ideas aren’t alien, but they don’t seem as realized as i’d like. i’ve always felt like this book was a key without lock, no door to open up (at least not in the way i want things opened), though there are plenty of items of interest. the book feels like a key for himself in many ways.

also, i never read this as a pseudo-system. and i don’t think he’d think it was a pseudo-system. i’d think he would believe in it, with revisions, etc. i mean, why do you take it to be “pseudo?” why isn’t it just a “system,” accurate or not? all philosophies are fictions, as William Gass tells us, but that doesn’t mean that when i read Gass and his theory of fiction that i think for one instant he doesn’t believe in the truthiness of his theory one-hundred percent. like Ezra here.

anyway, though, yes, meaning many-sided, certainly.

also, thanks on New Criticism and Pound. i see that now.

i also mean to say that when i read someone like Gass, i get a very clear sense of what the ideal book is. what that thing would be. i feel that that ideal thing is murkier here in ABC, though both (for instance) are starting with a similar cause.

I called it pseudo mostly because I read it as adopting the language and method of system without actually positing a system, if that makes sense. That is to say, he isn’t making a system, and he’s not particularly interested in making a system, but he has decided to convey his ideas through the verbal filter of a system. A quick example would be the one you picked: ‘degree’. There are not actually degrees here, he has not actually systemized the degrees, but the technical language of a system is crucial to the whole book, and much of Pound’s work, him being the perpetual writer of Manifestos that he was.

It’s part of what, I take it, that you don’t like about the book, and the main reason I talked about a ‘pseudo-system’ was that the questions you were asking were taking it to task for not being as systematic as its language seemed to indicate it was. I think the book is about as accurate on what it speaks as any of its sort has ever been, and that the primary grounds for objecting to it (like what yours seem? to be) are those of personality, namely Ezra’s. Also, mostly what I was saying with ‘hard time’ is that you already know exactly what he means, it isn’t alien to you, which means you’re asking what he meant to make a point (which does, in some states, qualify as a ‘hard time’). I could have used another phrase, though.

no, i know he’s not going to give us “degrees.” you obviously know a lot more about Pound than i know: why is “language of a system” crucial to the whole book if there’s no actual system? i mean this question completely sincerely. it seems like there is a system, it’s just kind of ambiguous at times.

what i mean: if he’s talking about great literature as that which is “charged” to an “utmost degree” and if he’s not going to explain how the “degrees” work, then how is the usage of “degree” charged utmostly? it seems, to me, the term is a bit superfluous – i mean, it’s certainly interesting, but the more i think about it the more vexing the term becomes, even empty. i don’t think this about most of the language in the book, but this part i do.

don’t get me wrong, i think it’s a great book; i’ve just always had questions about it and found parts of it mystifying rather than clarifying. not that that’s bad; i’m just that kind of person who can’t help but push for clarity. it’s a terrible way to be, i understand.

anyway, i do know what he means generally, but not exactly. and i’m not offended if i’m giving him a hard time (maybe i am) and you think that and you call me on it. that’s okay. it’s all goodness.

thanks

Well, like I said earlier, I’m not totally sure ‘degree’ was used to its fullest. If I bothered to spend time with the passage and the book, I could probably sort things out (including ‘degree’) more thoroughly. I don’t have a copy on hand, right now, so I’ll just stick with this: the language and the appearance, to the best of my knowledge, is a device Pound uses to fortify his voice in his works. If you’ve noticed, most of the time the voice is in fact rather effective, almost imploring. This voice set off multiple generations of writers, in several countries, and helped establish what it meant to be modern—but it is not without its vacuities, all the same. To lend your ideas a veneer of scientific authority, and then to infuse them with the enervating bark of the drill instructor, is to risk a little idiocy, now and again, which he sometimes shows. But mostly, in his more important prose tracts, the voice works: and it works because of this air of system, a system both real and absent; if it weren’t real, the book wouldn’t function, and if it weren’t absent—well, as to why he did not actually systemize it, I suspect two things: Ezra probably did not have the temperament, and he probably (and perhaps wisely) felt that the de facto systemization of cultural laws would be more distracting, limiting, and disorienting than he or his audience could have appreciated.

I do think it’s good to note that just because he did not broadly systemize does not mean that there is no system to this thinking. What I think is true 9 out of 10 times in his prose is that you can intuit the links in the chain where he did not elaborate. In one way, ‘degree’ is there to indicate that there are gradations of meaning–that, to his mind, it is possible for one work to contain more available meaning than another, and therefore to be more valuable than another.

yes, “intuit the links in the chain where he did not elaborate.” seems like what the book asks of the reader.

in any case, this explanation rocks. thanks for indulging me.

Last night I had a realization about the kind of style Pound was utilizing, and I managed to hold onto it long enough to haul it back here: Pound’s style sounds scattered as philosophy for those other reasons, I think, but also because his philosophical model was never Western. This book reads remarkably like the Confucian Analects, excepting the vast personality differences, which Pound translated (quite well).

I’m glad we came to something with the conversation. That seems to be a struggle on the internet.

it helps tremendously to know he was influenced by something like the Confucian Analects. i happen to have minored in eastern philosophy, though Confucius was never my favorite – still though, in terms of how those philosophies work, i can see a bit better the intuitive aspect Pound asks the reader to use. clearly i’ve betrayed my lack of knowledge about Pound here, but this really clears up some things for me. also, last night, i read a great essay by William Gass on who he calls “Ole Ez” and it followed remarkably close to what you’ve laid out here – though Gass, Western philosopher that he is, does indict Pound a bit for his lack of a system. still, it’s a great read in the book Finding a Form.

check out http://bit.ly/IndieLitSurvey cheerio from berlin.

[…] literature is simply language charged with meaning to the utmost possible degree.’ (http://htmlgiant.com/excerpts/literature-is-language-charged-with-meaning/). Language is one of the most important components of learning through literacy, it involves […]