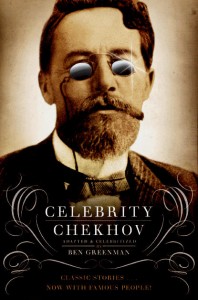

(Editor’s Note: A while back Roxane Gay reviewed Ben Greenman’s really fine short story collection, What He’s Poised to Do. Ben has another book coming out in early October, Celebrity Chekhov.)

“As an artist you have to have the confidence that it will be original once it passes through you.”

Ben Greenman is an editor at The New Yorker and author of numerous books of fiction, including Superbad, Superworse, A Circle is A Balloon and A Compass Both: Stories about Human Love, Correspondences, and Please Step Back. He also writes satirical musicals about the likes of Britney Spears and Sarah Palin; pens a political column by an earth ball; and maintains a website called Letters with Character that invites readers to write their favorite (or, in some cases, least favorite) fictional person.

This summer, Greenman’s What He’s Poised To Do was released by Harper Perennial; the Los Angeles Times called it “astonishing” and publications ranging from the Miami Herald to Bookslut agreed. His new collection, Celebrity Chekhov, publishes later this month. I met Ben in midtown and we wandered over to Bryant Park, where we discussed everything from a story collection’s “Albumness” to the potentially one-fingered Seth Rogen, whom Ben is famous for writing a comic letter to after the movie Superbad (same title as his book) was released.

Jaime Karnes: I thought we would start by talking about cupcakes. A moral compass, if you will. I believe you agreed to this interview because I promised you cupcakes.

Ben Greenman: Laughs. No, I agreed to the interview for two reasons: a) I like interviews; b) Because you had a suspicion of What He’s Poised To Do at first because of its cover. And then the suspicions were laid to rest, and I wanted to find out why.

Karnes: Well, there’s a faceless woman on the cover. I mentioned how boring and predictable I found it to be. When the cover of your book popped up on my computer screen, I thought fuck, here we go again, another faceless woman, another collection. Still, I read on and on. I then got in my car. I went home and read the entire collection. I got on your Web site, emailed you, promised cupcakes. I abhorred the outside cover of your collection, yet loved everything in the pages that followed.

Greenman: I know the painter; she’s a friend of mine. I love the painting. But also, I wanted a narrative painting. I think the front cover is a little misleading because you can’t see the man on the back cover.

Karnes: Is the cover art from the title story? Is the woman on the bed the receptionist from What He’s Poised To Do?

Greenman: We didn’t create them in concert, but that’s the closest story to it.

Karnes: Tell me how you feel about the marketing of books with faceless, most times headless women on their covers. Is it a necessary marketing strategy?

Greenman: I guess if it was a male painter, and the guy was in the foreground and she was on the back, murdered, it would have bothered me. But it seems more interior and justifiable. I don’t know.

Karnes: Was it for your book?

Greenman: No, no, it was done in 2006. I like the feel of it. I wanted it to feel a little old fashioned. It has a sort of starkness and sadness.

Karnes: Clearly music is an influence for you as a writer. You’ve ghostwritten Gene Simmons’ memoir. You write satirical rhyming plays. You wrote a novel that is about a fictional Sly and the Family Stone. Can you point your readers to your musical influences in this new collection?

Greenman: There aren’t any. I tried to keep pop culture out of here, mostly. I was reading in Boston earlier this year and a woman asked this same question. The only way music figures in this book is that the stories are organized like an album. There are short story writers like Mary Robison or Donald Barthelme who write a series of great singles, and so you can collect them in different ways. You can collect them as 40 as 60; you could put three. They may disagree. This is my theory. When I put a book together, on the other hand, I am obsessed with order, with which story starts, which follows, which closes the collection. I think of it as an album. The next to last story in this collection, “What We Believe But Cannot Praise,” is the “Layla” of the book.

Karnes: But many of the stories were published separately, and, in my opinion, they all stand alone.

Greenman: They do stand alone, but with the book I have to decide what to put in or what to take out and then I have to choose an order. So I took out this story that was one of my favorites because it wasn’t working in the order. Maybe it’ll go in the iPad version. For my next book, Celebrity Chekhov, we added a book into the iPad version after the book was done, which seemed strange.

Karnes: How does that work with your books’ non-techy mission? You argue often that we no longer communicate in effective ways, or that technology has somehow altered or severed real communication.

Greenman: Oh, I’m not a Luddite. I mean I’m not. I use email more than anybody. But if that’s your only reference point, there’s a problem. I mean I love technology, I have this stupid iPhone, I’m on Facebook, and for this book I got on Twitter.

Karnes: I was just about to give you shit about that.

Greenman: Oh, I will totally accept it; it’s all warranted. Harper Perennial kind of bullied me on there. What happened is they said if you don’t do it, you’re just not going to be able to reach everyone when you go on book tour.

Karnes: So your book argues for the superiority of letters. But is email any less permanent than a letter from the post? I don’t clean out my inbox.

Greenman: I think it’s actually more permanent. But email doesn’t have the interesting gaps that letter writing has. If you and I write letters, you have mine and I have yours. We don’t have our own. I have to remember what I said, and I have to feel like I’m sending you something valuable. With email we all have all of it all the time. I don’t clean out my inbox either, so we have the full record of all conversations. It’s not mysterious anymore. It’s not spacious.

Karnes: So you feel people don’t consider the emails they write?

Greenman: I think it’s more direct. You’re also writing to a person instead of a destination. Letters used to go to a place. Now, email moves around with the person. When you text, it goes right to the other person. It’s like firing off a smart bomb. There’s not the same kind of breathing room. And I do think unless you’re careful it can start to suffocate you a little now. You want an answer back right away, and then you have to answer back right away. A lot of time is spent saying nothing.

Karnes: But you talk about the permanence of feeling, right? You’ve said that how a person feels when they write a letter the receiver must then assume that the writer still feels the same by the time they receive it. Do you think this is really obstructed in email? Say I write an email to Donald Trump tomorrow, and I say, ‘Your show’s a pile of crap, your dynasty is falling, and you have a bad comb-over.’ Am I going to change how I feel in a week? In a month even?

Greenman: It’s not that everything changes. It’s that you own that set of feelings differently. And there are of course exceptions to every brilliant rule I invent. I was on the radio in Minneapolis this summer, a call-in show, and a steady stream of exceptions called in: a soldier, a guy who had to leave Somalia, an elderly man. They were all preserving the space and elegance of letter-writing, even when they were using emails. So of course there are kinds of emails that follow those patterns: very permanent and very heartfelt and extremely powerful. But sometimes now, texts go back and forth, and there’s so much micro-clarification, and anxiety that goes along with it.

Karnes: Speaking of anxiety, what about the mother in your story “Her Hand”? She’s desperately waiting for a letter from her son, who is away at camp. She’s pilfering the mail, shaking out catalogs. Isn’t that anxiety still alive via postman?

Greenman: Oh there’s always anxiety. I just think it’s different when you’re at home and you wait for a letter than when you’re on your Gmail and the header suddenly switches over from Roman to bold. To me, a font change isn’t enough. Again, it comes down to the balance between mystery and clues. When my Gmail tells me I have a new message, it also tells me who it’s from, starkly. When I have a physical letter in my hand, the clues come in at different rates. What’s the handwriting like? What kind of envelope? Thick? Thin?

Karnes: So for you it’s really about the physical object?

Greenman: I just think that maybe kids that are nineteen now won’t learn to read all of those clues. Of course, they’ll be grappling with different clues as they beam information directly from earring to earring.

Karnes: You cited Goethe, and specifically The Sorrows of Young Werther as an influence for What He’s Poised To Do. I can see that. Great book. But you’ve also taken from Goethe his quote on originality: “Everything has been thought of before, but the difficulty is to think of it again.” You put his quote on a little poster and then, beneath that, had yourself saying the same thing. Are you in search of a patch of originality?

Greenman: Yes. I’m not sure all writers are. Some want to show you the world as it is. Some want to use familiar forms to imagine the world as it should be, or shouldn’t be. I am preoccupied with the idea of originality, though. I like making things up that are a little risky. I’m not sure it always works to my advantage. Last year, I invented 3*TYPE, a 3-D type process that would capture all the excitement of 3-D movies. The invention was just a press release, very deadpan. But it was, I thought, all-new. Then a Belgian newspaper did something similar, and for a few days I was devastated.

Karnes: It’s like something that Raymond Carver said about The World According to Garp not actually being that at all. He said it was the very specific world according to John Irving. Is this the type of originality that you and Goethe are seeking?

Greenman: I can’t speak for him, but I will. Yes. Early on, I wanted to be the most original.

Karnes: But people called you clever. That’s not a nice thing to be called.

Greenman: It’s not? I see what you mean. It can seem dismissive, or trivializing. But cleverness is part of humor, or good design, or children, and as a result it’s part of me. With a story like “Blurbs,” from Superbad, I think I invented something completely new: it’s blurbs about the piece “Blurbs.” It’s also a satire of how people receive books, how reading happens, how opinion crystallizes.

Karnes: But you said satire is dead, right? Didn’t I read that you want to build a satirical graveyard? Of course, implicit in that comment is satire rearing or roaring its hilarious head.

Greenman: Yeah, I said it was dead. It’s not dead. But it’s easier than ever to find out who else has done it, and how, and that has a chilling effect. When I did “Blurbs” or a story like “What A Hundred People Real and Fake Believe About Dolores,” which is a kind of surreal mini-Rashomon, I was trying to make something entirely new, to blow the doors off the car. Obviously as you get older, as you become more aware of other writers, you can find other stories that are like yours. I look around long enough, say at every experimentalist from the 60’s, I will find something similar to that piece. Still, at the time, I thought I invented it. I wasn’t sitting with a figure model and copying. As an artist you have to have the confidence that it will be original once it passes through you. I’m not intentionally copying anyone but I’m also not stupid enough to think that an idea necessarily originates with me. It is just that this version of it does. It’s why I have stayed, I think, kind of experimental, even though readers might not agree.

Karnes: It seems that you’re exploring this idea of the human condition more so in this collection than previous works. I’m not going to assume a personal maturation on your behalf, but I must admit, that stuck in my mind as I read your work from new to old, in that order.

Greenman: You can assume that.

Karnes: There is something wildly different here from the character interactions in A Circle is a Balloon and Compass Both.

Greenman: Well, that book, which I published in 2007, was cartoonish to me. I don’t mean that in a bad or self-annihilating way at all, but the register was different. As I wrote it, as I thought of the women who inspired it, and the writers who were in my head as I wrote it, I imagined it all as bright colors, dots and things like that. Those stories are more idea-based than real-people-based. I think ultimately they’re complementary to the new ones in a way, but I don’t think maturation is the wrong word. I think that there may be a greater willingness on my part to articulate sadness. For a long, long time when I would do readings I would only read funny stories.

Karnes: Audience participation through laughter?

Greenman: Right. I couldn’t tell the difference between rapt attention and indifference. If I’m sitting here reading to you and you don’t respond, I don’t know how to read you. I’m not a performer. Maybe real performers can tell the difference, like classical musicians or serious actors. I have no idea, so it always scared me to read something serious, and so initially I leaned toward the funny side of the spectrum.

Karnes: Who was reading your books then?

Greenman: This is back in the early days of McSweeney’s. The audience was self-selecting: lots of young people, smart people, who wanted to see the world at a weird angle. I think a lot of us – Dave Eggers, Neal Pollack, myself – went to great pains not to be put in a ghetto of clever guys of a certain age. Fairly quickly, we all dispersed and did our own work. But there were articles at the time about the McSweeneys scene, and it felt like some people imagined it as a club, you know, like a writers room at SNL or something. Like we’d get together and Dave would say, “Hey Neal, which famous writer haven’t we parodied yet?” and I’d run out to get cigars and burritos. It was never like that. But I think we all maintained an interest in balancing comedy with sadness. I’m not sure if those guys, or anyone else, would agree, but that’s how it seemed to me.

Karnes: What do you think is funny in your new book?

Greenman: I think there are things about the Govindan story, which is about a karmic boomerang factory, that are funny. Some would say “quirky.” There are things about “A Bunch of Blips,” which is about a woman’s affair with a French intellectual, that are funny. But ultimately all of them are fairly sad. They’re much more about disconnected people and failure to right the ship. When they are happy stories, they tend to be more sentimental.

Karnes: Sentimental is a negative word in our vocation, isn’t it?

Greenman: Yes, but I would say that “To Kill The Pink” is sentimental in a good way. The protagonist is trying to figure out how he is going to do right by this person that he loves, which is a question people ask themselves all the time.

Karnes: And the story “Hope”? Not sentimental, but definitely a story of a man trying to find his way, if you will. A man trying to answer questions about interminable love that doesn’t even exist! I mean he can’t even mail the letters he writes; he has no address for this mysterious woman he met only one time.

Greenman: Yeah, “Hope. “ I have a friend who loves it. I have a friend who hates it.

Karnes: Not a close friend, I hope.

Greenman: Smiles. Let’s say she’s a friendly acquaintance. But she hates it violently. Something about the register of that story really bothered her. Perhaps the fact that the protagonist isn’t afraid to say things like “her mother was considered a great beauty.” That kind of language she saw as very…I don’t know if she would say lazy, but she saw it as very limited in its effect, and confined to a certain time. I don’t think that’s the case at all. I think the character, Tomas Tinta, is so much stranger than that: he’s writing letters to someone he doesn’t have and maybe never had. I guess my point is that I disagree with people who hate my work. But look, the funniest thing about any story collection is that they are Rorschach tests. No two readers ever like the same story. Like if I put you under hypnosis and I said okay let’s rank all the stories in What He’s Poised To Do, or Celebrity Chekhov, your ranking would be different from anyone else’s – and maybe different from your ranking a week from now, or a month from now.

Karnes: Does that bother you?

Greenman: I try really hard not to read reviews. My wife will sometimes send me snippets, but I probably stopped two, three books ago. What’s the upside? I know writers who agonize, or writers who get their heads artificially inflated. What I do know is that any critical response to any book will be, and should be, all over the map. I am highly suspicious of universal acclaim, just like I’m suspicious of universal derision. How many things are that clear-cut? It’s also why I am suspicious of The Big Novel, or The Crafted Tale, or The Absurdist Satire, or lots of other genres that people practice, some extremely well. I am always admiring of Jonathan Lethem, or Jonathan Franzen, or Nicole Krauss, or Gary Shteyngart, or Rivka Galchen, or Sam Lipsyte, or Darin Strauss, or Marcy Dermansky, or dozens of other writers. They do what they do so well, because they are themselves. Some of them enjoy more critical acclaim, or more commercial success. But again, they do it because they are true to themselves. That’s the only real target to hit, right? If I do the things I want to do as best as I can, and this book is a critic’s darling, and the next one is pulled out into the public square and beaten to death, that is a kind of success, believe it or not.

Karnes: Some reviewers were upset with the ending of the story “Down a Pound.” If I may inject my newly MFA’ed mind, I would charge that story with what we liked to throw around the round table (though I’m not convinced everyone knew what it meant): a “pat” ending. It ties up so neatly, seemingly forced. Did you have that ending in mind as you wrote, or did it come organically?

Greenman: I’ve heard all the same rules as everybody. Don’t kill the main character: that’s an easy way out. But still and all…

Karnes: Fuck rules, right?

Greenman: I agree. And I think that you really have to think about why those rules are there. People don’t. Classes are taught. But if no rule were ever broken, we’d have fiction that’s product. With that said, there are some people who have read that story and are genuinely shocked and saddened by that ending. Some people read it and say Oh! I didn’t think she was going to die. Why did you kill her? They are betrayed by my choice. My feeling is that it is like anything else. Say you look at a painting and you wonder why is it this size, or why doesn’t it have fewer inches at the top. I don’t know. I mean sometimes it’s because the canvas comes in that size, but sometimes it’s because you as an artist see it that way.

Karnes: The world According to Ben Greenman.

Greenman: Yes. I know why I killed her.

Karnes: Is it fair to say that story earned its ending?

Greenman: If a collection is an album, each story is a song, and songs end in one of two ways. They either have an outro where the volume goes lower and lower, a fadeout, or they’re done quick with a strummed chord or a cymbal crash. I like the idea, formally, of playing with that. Some stories trail off; they have equivocal moments. Some crash out.

Karnes: Are we talking about plot-driven stories?

Greenman: Plot, yes. But even just the way the language carries you. People don’t like it; they think it’s too showy to end with “and then the bomb in the suitcase blew up.” They think that kind of thing belongs to genre fiction. But one of the most interesting things to me as a writer is how people end things. David Gates, for example, is great at ending chapters. In a book like Jernigan or Preston Falls, it’s objectively true that every chapter ends well.

Karnes: So we turn the page.

Greenman: Yes. But they aren’t necessarily cliffhangers. There’s just something there that pushes you forward into the next moment in this invented world.

Karnes: I spoke with Victor LaValle about this earlier this year, concerning his novel “Big Machine.” I already knew Stephen King had influenced him, but I wanted to ask about his novel’s form. In other words, why am I so dedicated to beginning the next chapter when I’m tired, or need a break, or just naturally expect chapters to give readers pause. He said he did nothing original. He suggested I go back to Melville, go back to Moby Dick. But let’s segue back to endings, okay? How do you know when a story is finished?

Greenman: Often the end is written, or at least conceived, before the middle, in the sense that I know if I want the story to end with a certain note. They can end with a meaningful moment with a character, they can end with a symbol, with dialogue. Just technically there are a limited number of ways a story can end. You pick which conventions you’ll respect. I guess the best example I can use (and it’s not a good one but I’ll use it anyway) is Curb Your Enthusiasm, where throughout the story you know – because of how Larry David has built the show, or how he built Seinfeld – that all the threads are going to come together.

Karnes: No severing off of characters or small players?

Greenman: Right. And if he did that, it would be a hugely subversive move for that format. If two minor characters surfaced, say a bum and rich guy, and they didn’t somehow have a conflict in the final act, you would say that was the most experimental Curb ever. Like what happened? Did they pour acid on the videotapes before airing? With stories you have a lot more freedom. In previous books, experiments were higher on my mind, like the mobius strip story that John Barth published in “Lost in the Funhouse”: there’s a story that you’re supposed to cut-out and put on a turntable, and, it says “Once upon a time / There was a story that began” and you’re just supposed to watch it spin round and round like that forever.

Karnes: Thus, of course, never really ending.

Greenman: Never really starting either. I’ve always been preoccupied with experimental fiction: the questions it asks, the way it works. I do think, for What He’s Poised To Do, I wanted it to be more conventional. So I set aside some of the construction of the product that has preoccupied me in the past—pairing stories off, making sure there were tons of internal echoes.

Karnes: Are these stories speaking to one another?

Greenman: Yes, but not in the same way as before. I thought about having characters surface with the same names, but that seemed too much. Though it’s something that interests me. If you were reading a book of stories, and two stories next to each other had characters with the same name, you would assume (like ninety-nine percent of all readers) that they were one in the same. In theory, of course, the men might be two different guys named Steve, but if you were an editor, you’d nix that as a bad idea. The way that people experience this media, you’d say, prevents us from having two different Steves in consecutive stories side. Too confusing.

Karnes: You think names are arbitrary?

Greenman: They can be. Bob Mankoff, the New Yorker cartoon editor, and I have spoke about this at great length, because, you know, the New Yorker has the convention of generic names for business types: you know, “Robinson, report to the file room. There is someone there to see you.” And then, I don’t know, there’s a dinosaur in the file room. You can’t name that guy a strongly ethnic name because you’re bringing too many associations into the cartoon, where you want the joke to be skeleton, clockwork. In Superbad, I played around with names quite a bit: names that were the reverse of other names, rhyming names, similar names. I wrote a piece that was a big fight scene between two men named Ray. So it’s Ray and Ray, and by the third sentence it’s totally confusing, you have no idea who’s winning. I probably have an over-developed interest in how people read. You know, like all the weird little markers: what’s at the bottom of the page, what happens when you turn the page. When Superbad came out I put typos into the book on purpose.

Karnes: Intentionally?

Greenman: Yeah, and then I wrote a piece for McSweeney’s about it. Because if you’re reading a book and you notice a really egregious typo, you could have a couple different reactions. You could think, oh he has a bad editor, this is a cheap house. Or you could feel yourself moving into the book more intensely. It depends on the reader and the text and the relationship between them.

Karnes: Not that I’m supposed to go back and reread for something I may have missed?

Greenman: It can give you ownership of the book in a certain way. It can embed you deeper in the book. And so I’m interested in that, but I think the trick to being that kind of author is how to balance that kind of text engineering with the more basic but maybe more difficult process of just giving someone a good story.

Karnes: To be conventional, or not. I get it. Back to names. Did you know that a possible anagram of your name is BARN GENE MAN? Mine’s Insanely Mean Jerk, but we can wait till the interview is finished for you to comment on that. I have a three-part question to go with this. BARN we’ve already covered. GENE is Gene Simmons, whose memoir you ghostwrote. Gene makes me think of a question about reality, and in his case reality TV. Is reality real in the sense that we experience it episodically? Is what we see on his television show the man you wrote about?

Greenman: You mean the World According to Gene, like that kind of idea?

Karnes: Yeah.

Greenman: I think that Gene is a very different kind of person than I am. I think that’s fair to say. But I have a type of admiration for his type. Which is that he years and years and years ago he made this thing: this man, this brand, and he’s fairly shameless, but not in a horrible way. He’s just about extending his brand. It’s Trump-like. That mentality.

Karnes: Did you learn anything writing his book that has informed your own fiction?

Greenman: Yeah, I think for Please Step Back it did. I heard stories about rock-star debauchery and about the business. But on a more fundamental level, I got to see that Gene’s identity was always hidden behind make-up so his real self was safe. Gene was very deliberate in separating rock n’ roll Gene from normal Gene. To me it’s curious, because writer hides behind different kinds of things, but they still hide.

Karnes: All right, so back to your anagram. We’ve covered BARN and GENE, now for MAN. Where are all the gay men in your writing, or rather, why do these stories only deal with heterosexual relationships?

Greenman: I don’t know. Because I’m not gay and I wouldn’t presume to say that gay relationships are exactly the same as the ones I’ve been having, maybe? That’s not to say that they’re so different, or even different at all, but that’s for the reader to decide, not me. A gay man can read my book and identify with it, but should I write gay characters?

Karnes: You’re not black, and that didn’t stop you from writing “Please Step Back,” which was a novel about a funk-rock star from the late sixties.

Greenman: That’s true, and some people objected. It’s a good counterexample to my argument about presumption. I guess I’d say that the characters could easily be gay in some cases but it never occurred to me. So many of these things for me are about pretty specific experiences. Then I have to distort them to make them fiction and decode by switching to the other side and imagining the woman’s role.

Karnes: Which you do well.

Greenman: Thanks. But to answer your question, I don’t know why there aren’t any gay characters. It’s an interesting question. I wonder what percent of gay writers write mostly straight characters. I was reading in Philadelphia and some guy asked me why there weren’t Asians in my novel “Please Step Back.” I couldn’t remember, because as I was writing it, it was very heavily a black/white book about race relations in the sixties. The guy accused me of being slightly xenophobic. The reading ended. Later on, someone sent me a post from a Web site. I had judged a fiction contest and I had called someone xenophobic as a joke. That guy had started a campaign where he would send people money if they went to my readings and accused me of being a xenophobe.

Karnes: Did it go viral? Were there picketers?

Greenman: It went minor viral. It wasn’t like bird flu.

Karnes: No antidote necessary?

Greenman: No. But it’s such an odd idea, to do a census of a book. Any work of fiction is necessarily exclusive, unless you deliberately set out to include everyone, and that’s an experimental novel.

Karnes: Are these stories autobiographical?

Greenman: Yeah. I think they’re fairly documentary. Say I have a friend and I notice that she starts to act differently to her brother, and then I investigate further and I find out that this guy that she’s dating sort of resembles her brother in some way, then that’s an interesting arrangement that I would then try to draw out in fiction. I’m not trying to come to conclusions about that person’s life but I am identifying and exploring oddness.

Karnes: Speaking of oddness, you have a story set on the moon.

Greenman: Right. “17 Different Ways to Get a Load of That.” It’s the second story I have set there. For me, the reason is simple. It’s about alienation. It’s getting harder and harder to feel far away from people. One of the things about email is that if your girlfriend is in India, she is no further away than if she is in Indiana. You can reach her in a fraction of a second. I thought I could overcome that by setting it on the moon where there really is distance.

Karnes: In Steve Almond’s review of your book in the Los Angeles Times he refers to you as a “reluctant romantic.” Are you?

Greenman: Well if I were reluctant I wouldn’t admit it, would I? I think it’s an odd word, again because I think it conveys a kind of dopiness, or laziness. Like it has an implication of idealism, in that you aren’t seeing the world for what it really is, and eventually you’re going to be disappointed. But if he’s saying that I am reluctant because I am resistant to those poses but am, deep down, sympathetic to the possible result, then he is right.

Karnes: How do you manage to work full-time as an editor at the New Yorker, write books, write musicals, be a good husband, I’m assuming, and raise your sons?

Greenman: The boys raise themselves. As it turns out, though I would have never guessed it, I have a lot of energy for people. A few people: close friends, mostly. But I talk to them about their lives, which either exhilarates or upsets me, and then I have to make sense of it on paper.

Karnes: When or how did the fiction writing figure in?

Greenman: It was there early. I’m not one of those writers who will say that all of my early stuff is bad. Some of them were good; they were just written by an eighteen-year-old, you know? And then in my early twenties when I was in grad school, I started writing more, and I had good success for about a year and I thought this is pretty easy, like I must have an original perspective or something.

Karnes: The Midas touch.

Greenman: Yeah. So then after about a year I started getting a lot of rejections and I hated that, so I stopped trying to publish. I never really stopped writing. But for three or four years, I took it very hard. I got angry at myself and at them. All the bad aspects of my personality were on stage. People would write these really nice, encouraging rejection letters and I would go to sleep and dream of going to that person’s house and chopping their head off. It’s the worst rookie mistake you can make as a writer, to not prepare yourself for the ninety percent rejection even as you bloom inside from the ten percent acceptance.

Karnes: To build on that: What’s the difference between people who publish books and people who are writing in to your Web site Letters With Character? These aren’t “writers.”

Greenman: No, and in fact, it’s been fascinating how well-written the vast majority of them are. I think the professionalization of writing is a really vexed question because the points of entry are so numerous now. When I was a kid, even making a zine required lots of tools and a certain amount of capital.

Karnes: It required effort.

Greenman: Yeah. And now the distance between thinking you want to express yourself and expressing yourself is greatly shortened. That has some great effects and some bad effects. One of the effects is that it exposes large numbers of people to an affliction that used to only affect a small number of people, meaning writers: your ego can come to depend so much on whether people like what you’re putting in front of them.

Karnes: You’re talking about your audience.

Greenman: But who knows what that even really means anymore. This summer a man wrote me to say he was highlighting sections of my book and his wife accused him of having a crush on me. He had access to me via email. He made use of it.

Karnes: And?

Greenman: And so when those kinds of messages come in you feel gratified for a certain amount of time.

Karnes: But it’s fleeting?

Greenman: It depends on who you are. But I’m probably like a lot of writers. My wife says that a good piece of feedback will satisfy me for 10 minutes, and a bad piece of feedback will stick in my head for three years.

Karnes: I don’t think that’s uncommon in our field.

Greenman: No. That’s why I stopped reading reviews like three books ago. But it’s probably necessary in a good way. I mean as a creative person, if you only filter for the good things, I don’t see how that could benefit you.

Karnes: I wanted to steal from your own interview with Rhett Miller and throw a lightning round at you? What’s the most difficult letter that you’ve had to write?

Greenman: I would say the hardest letter I wrote was to a girl in my early twenties – I don’t know if it ever reached its destination – I was living with a girl in Chicago (she was a painter) and we were having a bad time of it, and I went on a trip so we could think about things and when I came back she was gone and all my stuff was shoved in to a closet. And I wrote a letter trying to make sense of it. It was the first big emotional injury done to me in my life. So I wrote a letter asking what the hell had happened? Though I’ve written many angry letters.

Karnes: I know. Like the one to Seth Rogen where you threatened to chop off his finger with a hatchet.

Greenman: We met at the New Yorker Festival shortly after that. David Denby was interviewing Judd Apatow and Seth. He was very nice. For about four seconds I felt bad about threatening him.

Karnes: I have a crush on him.

Greenman: If I see him again, I’ll get you a finger. No, wait: I’ll get them all for you.

Karnes: That’d be lovely. So what’s the one story that makes you cry?

Greenman: Well it wouldn’t be a story; it’d be a novel. “Where the Red Fern Grows,” which is maybe true for every boy.

Karnes: It’s a guy thing.

Greenman: What’s yours?

Karnes: “In the Cemetery Where Al Jolson is Buried,” by Amy Hempel. Gets me every time.

Greenman: Good one.

Karnes: What’s the one story – or I suppose we can open this to novels – that pisses you off?

Greenman: I’ll only answer that evasively, which is to say that if something starts to make me angry I go in to analytical mode as an effect. Take Tom Robbins. As a kid I really liked him. Now I really like him. But in my twenties something went haywire and I didn’t. In a way he’s like a relic; post-hippie sex fiction that can come off as counterculture cliché if you’re not paying attention. Now, as I say, I like it again. I can see the things I like. But I went through a period when he made me mad.

Karnes: For me it’s Nam Le’s “The Boat.” It pisses me off because it’s so fucking good, you know?

Greenman: Oh, so for you it’s envy? Well then I guess I should add a footnote to what I said before, because I don’t read many of my contemporaries. I hope it’s not envy. It might be, slightly, but it’s more about keeping channels clear. That and I like to go back, go far back, and find the stylists, the people who did extremely interesting things with prose in extremely interesting ways. They don’t have to be Henry James or Laurence Sterne. There’s Barthelme, and Cheever. There’s Mary Robison.

Karnes: Okay, so we already know that Cotezee and Goethe and Nabokov were influential for your epistolary endeavors. My question is who are your three female literary heroes? I’m going to ask you something dirty about them, so choose carefully.

Greenman: Alright, I will say, although the reasons are very strange for all these women, like they are for any hero. Let’s say Mary McCarthy for one, for rigor and intellect. Then George Eliot for the sweep of the prose and a certain broad vision. And then – this is a weird one. There’s this book, a Vintage paperback in the called Elbowing the Seducer. It’s a book about New York and sex and the art world of that time. I remember reading it and thinking it was a good, solid, unpretentious novel. It was written by a woman named T. Gertler.

Karnes: So assuming Mary McCarthy, George Eliot and this T. Gertler are all alive, I want you to play Marry, Fuck, Kill with them.

Greenman: I knew that was coming. So if they’re all alive, I guess Fuck is probably Mary McCarthy. That seems like the logical thing to do.

Karnes: I agree.

Greenman: Um, I guess reluctantly I’d kill George Eliot. I’d feel terrible, but I’d drown her.

Karnes: No? Like rocks in her pockets? You’d Virginia Woolf her?

Greenman: Yeah, I’d take her to the river and tell her to stand near the edge. I’d tell her it was just research for her next book.

Karnes: So then that only leaves one choice.

Greenman: Well, T. Gertler I don’t really know anything about, I just really liked the book, so I guess I’d marry her. She’s probably the closest in age, too. I’d have to say that it was a formative book. Looking at this androgynous initial, right, wondering if it was a woman writing. I was young and that was meaningful.

Karnes: Last question. I was going to ask you what’s next.

Greenman: The new book is called Celebrity Chekhov. It’s been marinating in my brain a while. There are all these Chekhov stories about love that I go back to over and over again; I think he’s a very different writer than I am, but he’s always really good at insights of people. I’m not saying anything new; everybody knows that. He’s Chekhov, for God’s sake.

Karnes: And?

Greenman: And I think because the dominant translation of these stories is old-fogeyish, the characters seem much older than they are. I think he’s writing about very contemporary people in way – in terms of their envy and the way they deal with class and negotiating public and private space. But it’s hard to see them as contemporary with gas lamps and coachmen. SO I had this idea of replacing his characters with modern celebrities. Conan, Britney, Letterman. Oprah. The effect of it is very strange, because these are very moving stories, and there are celebrities that mesh with them in fascinating ways. Sometimes the fit is perfect. Sometimes it’s intentionally, surreally bad, and sometimes the pleasure is in the disorientation.

Karnes: Your entire posture just changed. You had a lot of fun with this book, didn’t you?

Greenman: Oh yeah, a lot of fun. What Harper Perennial and I are interested in seeing, I suppose, is how it’s received. It’s hard to say if it really matters, but it’s interesting, because this, as opposed to What He’s Poised To Do, is a book that exists, in a way, through its audience. In other words, we’re saying to the audience: this is how you have been reading these stories, and now it will change slightly. Do you want to push back, or go quietly, or some third thing?

Karnes: Are you really saying that to the audience? I mean how many people who watch Oprah read Chekhov?

Greenman: No, and that’s what’s interesting about it, because they know who Paris Hilton is.

Karnes: So they’ll want to read your pop culture version?

Greenman: Who knows? Who knows who ever wants to read anything? Still, after this very intense book of stories that are, on some level, entirely about people that I know, it was a relief to suddenly step back and do the opposite. Speculate wildly! Be irresponsible within limits! Both are part of writing.

Jaime Karnes teaches fiction writing at Gotham Writers’ Workshop, and English at Rutgers University. Her work has appeared in Storyglossia and Willard & Maple. She works at Granta Magazine and lives in Manhattan.

Tags: Ben Greenman, Chekhov, Harper Perennial, The New Yorker

Fucking great interview. Thanks for this.

[…] http://htmlgiant.com/feature/a-dementedly-long-interview-with-ben-greenman-by-jaime-karnes/#more-437… […]

It is really long! But also good!

Wow. Great Q & A.

Seth Rogen’s fingers: Hell yah. Also, drowning Eliot: great answer. This interview rocks.

[…] * Here is a long interview with Ben Greenman. […]

I guess my point is that I disagree with people who hate my work. But look, the funniest thing about any story collection is that they are Rorschach tests. No two readers ever like the same story. Great Post!

This is a really interesting one i loved reading it.

difference between google plus and facebook

A Dementedly Long Interview with Ben Greenman by Jaime Karnes | HTMLGIANT