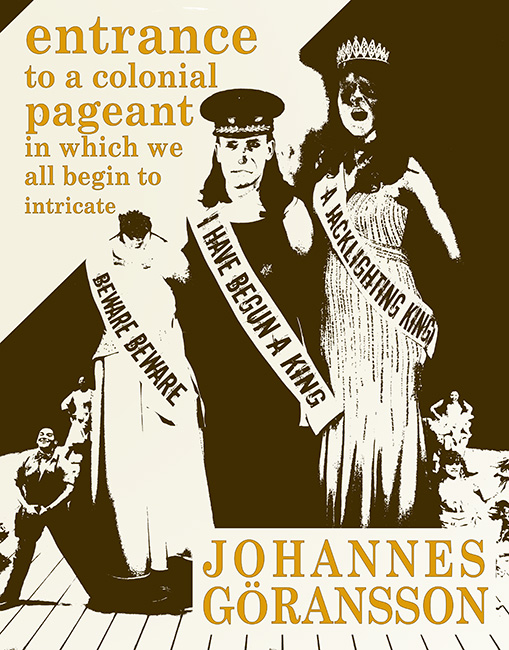

I can’t say enough about how important the work of Johannes Göransson has been to me, both as a field of language and image, and as a person. Besides co-editing both Action Books and Action Yes, two places where you can always depend on reading work that is new, singular, challenging, and actually fun, he has published four full length books of his own work, including Dear Ra, A New Quarantine Will Take My Place, Pilot, and most recently Entrance to a colonial pageant in which we all begin to intricate from Tarpaulin Sky, as well as translations of important Swedish writers like Aase Berg and Johan Jönsson [if you haven’t read his Swedish issue of Typo, holy shit], and wrangling of the insane machine that is the hybrid litblog Montevidayo. Not to mention being a teacher (which, when reading some of his students’ work, and what mechanisms he gets out of them so early, equals a particular feat), a father, a husband, and a person. In no small words, a fucking force.

Over the past few weeks I exchanged emails with Johannes about all of the above and more.

* * *

BB: I remember reading pieces of the Pageant years ago I think under the name New Torture Operations, yeah? How did this project begin and manifest itself into the book it is, on an assemblage level?

JG: Yes, I think that was one early version of what became, among other things the pageant. It also became the second half of the performance piece The Widow Party and my novel Haute Surveillance (which is not published). Assemblages do play a big part in the way I compose these. In part they come out of a piece I wrote over a couple of years a few years ago, The Black Out Sessions or The Secessions (it has many names), and which I haven’t and won’t publish (well I did publish some of them before deciding that it wasn’t the right thing to do), but from which I create various assemblages – such as in The New Torture Operations, The Widow Party and Pageant, all of which form assemblages between torture and fashion, the anorexic body and performance, atrocity and kitsch, colonialism and the nuclear family.

When I was working on these Black Out Sessions I was also studying Brazilian-Swedish artist-poet Oyvind Fahlstrom’s work from the 1950s and 60s and he uses this funny pun – he doesn’t make “collage,” he says he makes “kalas,” which is Swedish for “party”. And the way this works out is that his artworks parties (though it’s usually translated as “feast”) on other works of art or texts. So there’s a party on Mad Magazine, or a party on Burroughs etc. So the Black Out Sessions were parties on just about anything I could find. I was both very creative and totally unfocused so I decided this wasn’t a finished text but something that I would party with/against/on with these other manuscripts. The Black Out texts became a kind of “party” energy which I used on other texts and subject matters to form assemblages. In the particular pieces that are in The New Torture Operations and pageant are parties on this 19th century antique textbook a student gave me years ago – what every student needs to know about the world. This includes chapters on astronomy, “The Vasty Deep,” and “The Flowery Kingdom” (China). A lot of what a student needs to know, it turns out, is about the morality of various colonial ventures (Stanley and Livingston get their own full chapter). Interestingly my home country of Sweden gets I think one sentence in a paranthesis and it’s something like “… (in difference to the Scandinavian countries, about which not much is known other than that they are the ugliest and least intelligent of people).”

But then at some point I decided that it would have to be a pageant. I think I decided that after doing The Widow Party performances in Chicago, which was such an amazing, electrifying experience for me. One key influence in this choice was the pageantry of Abu Ghraib, which figures heavily in The Widow Party, and this made me think about JonBenet Ramsey, how her death seemed according to the TV news to be foreshadowed (or almost equated) with her pageant participation, so that the artifice of her getups was seen as a kind of violence on par with her murder.

But then at some point I decided that it would have to be a pageant. I think I decided that after doing The Widow Party performances in Chicago, which was such an amazing, electrifying experience for me. One key influence in this choice was the pageantry of Abu Ghraib, which figures heavily in The Widow Party, and this made me think about JonBenet Ramsey, how her death seemed according to the TV news to be foreshadowed (or almost equated) with her pageant participation, so that the artifice of her getups was seen as a kind of violence on par with her murder.

Also, one of the main causes for the pageant was when my daughter Sinead and I were out walking one day in our city in Indiana and we came across this boy who was naked except for a too-small “dream team” basketball jersey from the 90s. He mumbled incoherently. I tried foolishly to talk to him, then these other people came and called a cop and he was taken away. I thought about him as the opposite of JonBenet – naked and mumbling in Indiana, instead of dressed up in front of cameras and singing. So that became one of the main characters, Miss World. So then I formed an assemblage between artifice and abuse. And I fused Courtney Love and Genet in him. I didn’t want him to be a victim child. I wanted him to forge a connection between contagion, artifice and crime. Singing and mumbling: I wanted these modes of language to be part of the dynamic.

BB: I found it interesting that there were all these forces at play, and at times the Passenger, your central character to some extent, seemed like a foreigner, but also an American, as if he were both a transplant and a staple of the terrain that the book takes place in. The book specifies at the opening too that its second stage, the one where your daughter (who is never seen) dances is in South Bend, Indiana, while the other settings, one “full of ornaments and crime,” the other a mall, could be anywhere, but also felt to me throughout as that familiar claustrophobic and constantly opening space of media and bodies that feels particularly like the psychic lockdown state of the U.S. Do you see this as an American book? Does that matter?

JG: Yes, that’s the way I see the book too: This motion from the local to another place. The cramped physical space to the mobile. The location is in one sense very specific but it is also supposed to open up. That’s the poem. Kyle’s review of the book did a great job analyzing this effect. The passenger is an immigrant figure, but even the natives tend to not be entirely unforeign (in fact they act quite a bit, suggesting they’re a bunch of fakes). The family exist as a kind of colonial outpost, so they’re not native though they are in charge. Is this an American book? I would say it’s an American book like a tourniquet. A riding lesson. Like Abu Ghraib is an American movie (teenagers smooching in the back). Like we’re in Kansas, but we’re in the whirlwind. When Sinead first saw Wizard of Oz, she said: “This is scary.” And I said: “Should I turn it off?” And she said: “No! I like scary.” That’s what my attitude tends to be as well.

JG: Yes, that’s the way I see the book too: This motion from the local to another place. The cramped physical space to the mobile. The location is in one sense very specific but it is also supposed to open up. That’s the poem. Kyle’s review of the book did a great job analyzing this effect. The passenger is an immigrant figure, but even the natives tend to not be entirely unforeign (in fact they act quite a bit, suggesting they’re a bunch of fakes). The family exist as a kind of colonial outpost, so they’re not native though they are in charge. Is this an American book? I would say it’s an American book like a tourniquet. A riding lesson. Like Abu Ghraib is an American movie (teenagers smooching in the back). Like we’re in Kansas, but we’re in the whirlwind. When Sinead first saw Wizard of Oz, she said: “This is scary.” And I said: “Should I turn it off?” And she said: “No! I like scary.” That’s what my attitude tends to be as well.

[Johannes reading his poem “Trauma” for Jubilat]

BB: How did the idea of changing the shape of the book into a pageant alter the way it was assembled? For instance, the stage directions are really compelling as action, in that most of the work itself is done by voices, and often the directions are simply conditional, sometimes based on previous media, taking cues from The Fall of the House of Usher and the Twist. I’m interested in how your infatuation with the pose or the gesture operates between the actual speaking, which ends up giving what could be a simpler series of poems a kind of growing body that accumulates as it continues.

JG: Yes, you’re again very correct: I’m infatuated with the way Art and the Body interact, and the role of violence in that interaction. I think again that came from The Widow Party. I first wrote that play while recovering from a car crash. Everything was a little hazy, a little achy, a little jammed up. I watched a documentary about the 1960s (the widows are the black one and the white one from the assassinations of this era). And reading about our wars and so on. So the body was deeply involved with art and violence from the start: in my own body, hammered, watching acts done to other bodies. And then seeing this piece actually performed was so thrilling and unnerving; the way these violent motions and actions were brought into/onto the bodies of the actors, of the audience. In response to the show, I remember poet-blogger Josh Corey saying he felt uncomfortable with the lack of critical distance from the violence, and that’s what I found so thrilling and unnerving about it: the way the violence penetrated the bodies. Sometimes it’s hard not to see Art penetrating everything: like the macabre pageantry of the boy I found in the backroads of Indiana. Or MLK’s widow with her stunning outfit. Or (at its worst) our government’s metaphoric visions of war. Or how when I first came to this country as a teenager, I was attacked for the clothing I wore. I love “The Fall of the House of Usher” because it shows everybody, everything possessed by art, everything collapses into the eye-wound-lake. I love the sister who is/ins’t dead, a body seeming both killed and animated by Art. A little like the un-kill-able girl in Ringu, who seems to be animated by the duplications of artistic montages. The Twist is such an amazing name: since it suggests a horribly torturous movement. Something Patti Smith brings out in her song on “Horses.”

JG: Yes, you’re again very correct: I’m infatuated with the way Art and the Body interact, and the role of violence in that interaction. I think again that came from The Widow Party. I first wrote that play while recovering from a car crash. Everything was a little hazy, a little achy, a little jammed up. I watched a documentary about the 1960s (the widows are the black one and the white one from the assassinations of this era). And reading about our wars and so on. So the body was deeply involved with art and violence from the start: in my own body, hammered, watching acts done to other bodies. And then seeing this piece actually performed was so thrilling and unnerving; the way these violent motions and actions were brought into/onto the bodies of the actors, of the audience. In response to the show, I remember poet-blogger Josh Corey saying he felt uncomfortable with the lack of critical distance from the violence, and that’s what I found so thrilling and unnerving about it: the way the violence penetrated the bodies. Sometimes it’s hard not to see Art penetrating everything: like the macabre pageantry of the boy I found in the backroads of Indiana. Or MLK’s widow with her stunning outfit. Or (at its worst) our government’s metaphoric visions of war. Or how when I first came to this country as a teenager, I was attacked for the clothing I wore. I love “The Fall of the House of Usher” because it shows everybody, everything possessed by art, everything collapses into the eye-wound-lake. I love the sister who is/ins’t dead, a body seeming both killed and animated by Art. A little like the un-kill-able girl in Ringu, who seems to be animated by the duplications of artistic montages. The Twist is such an amazing name: since it suggests a horribly torturous movement. Something Patti Smith brings out in her song on “Horses.”

BB: That is one thing I really love about your work, the invention of things objects or gestures that are given space often only as names, or as employments, which also often reference bodies outside the text that then become admitted: the Red Robe of History, the Passenger, Bird-Child, Father Exchange, etc. Burroughs did that all the time, and to an effect that feels similiar here. These words are also employed beside clear historical figures like Charlotte Bronte and Baghdad, etc. The way they are inculcated and then used as tools, forms that the language does violence on or absorbs and then allows to just be, really make the book bigger than if they were to use those images more explicitly, the way so much other writings want to do. Would you talk about this method of both borrowing from culture, and creating culture, and smearing them together almost in a collage way rather than by narrative (though narrative, by its sheer nature, appears). What is the function of image vs. moniker to you?

JG: Blake, again I’m startled at how closely you’ve read my book. I have not really consciously thought about this dynamic, but I can see now that this is something I do quite a bit of. If I get your argument, you’re taking note of the way the text interacts with figures from “outside” of the text and that I don’t fully integrate them into the text. My feeling is that I want the text to function like a conduit of violence, an interaction, not a separate autonomous space. I don’t want the text to be an authoritative description of a historical context. I don’t want to be Charles Olson and folks like that – I don’t want to be a documentor. I don’t think of art as separate from the world, nature etc. Nor am I interested in art which claims to be part of the world; art that claims to not be art. I am interested in art that is invested in its own Art-ness – with all of its crass devices and costumes, all of its kitschy metaphors and pageantry, all of its infected toys. On the other hand I’m not interested in creating a kind of refined space of contemplative art either, I don’t want art as an escape. I suppose in all of these what I object to is a kind of stability, a kind of space that art depicts or documents or provides. I’m more interested in art as violence, art as a haunting, as a spirit photograph, as what Aase Berg calls a “deformation zone” or what Joyelle has called “necropastoral.” (Joyelle’s actually right now downstairs playing some gloomy Cure song from the 80s for our daughters.) Art that is both Art and a contagion in the world. By not fully accounting for these figures, what I want them to be is this unstable matter. I want it all to be kind of shitty, you know.

BB: I was wondering what you think about the idea of metaphor in this context. A lot of people seem to need to give context to work like yours that makes hybrids of these violences and images into a metaphor for something, but I’ve always thought of the sentence as a function of the real. That it creates the space it exists in, and is not a metaphor. To separate it is damaging to both ends. As a teacher and a father, I wonder if there are methods you can use beyond the writing to bring people beyond placing the work in those ways?

JG: This is another great question. On some level, “metaphor” is something I’ve always been very interested in, but the more I think about it, the less certain I am that what I’m writing are metaphors. I’m not even certain I know what metaphors are. If it’s the new critical idea of vehicle/tenor then I don’t really relate to the idea: the relationship seems to stable and too separate. I want my tenors to be vehicles, my vehicles to be tenors. This is another way I suppose of saying that I agree with you that my words are not metaphors “for” something. Some of my influences when I started writing were the letters of insane people (and serial killers) and drug-related writings about hallucinations, and in part what I liked about this was that they were not exactly metaphors but something more literal – literally fake. At the same time I read a lot of Surrealist writings and Rimbaud and from them what has stayed with me is a sense of alchemy, a sense of metamorphosis (rather perhaps than metaphor). So in some sense I guess I’m approaching writing as something a little less stable than the term “metaphor” implies. On the other hand, I love the idea of using devices like metaphor and simile because they’ve become such kitsch items in contemporary “experimental writing.” But the very word “like” (in a simile) has its own effect – tchotchki-like no doubt, but an effect nevertheless. I do think about my writing (and others writing) in pretty spatial ways: sometimes I like to open the space up, sometimes I like to create a claustrophobic space, other times I want to shut the space off.

As for sentences: I love sentences. About 10 years ago I decided my sentences were not good enough so I wrote a few notebooks full of the best sentences I could find (Nabokov, Genet, early Delillo etc, but also non-literary sources, film etc). I’ve been using those sentences ever since. But now I feel they’re not quite right for the project I’m working on, so I’m generating a new set of sentences, sentences (and words) having to do with plagues and fashion mostly.

BB: Has becoming a father changed your methods or thoughts?

JG: I don’t have as much time any more anymore. I’m more exhausted. But kids also say funny things and look at the world in funny ways. Aase Berg has a fantastic essay about the connection between poetry and psychotic relationship between mother and child. One enters into a little cocoon where language is different (full of “poopee” and “peepee” but also puns etc – the other day I asked Sinead if she remembered “farfar” (grampa) and she said “he lives far far away”). I’m sure this psychosis has affected me in some way.

JG: I don’t have as much time any more anymore. I’m more exhausted. But kids also say funny things and look at the world in funny ways. Aase Berg has a fantastic essay about the connection between poetry and psychotic relationship between mother and child. One enters into a little cocoon where language is different (full of “poopee” and “peepee” but also puns etc – the other day I asked Sinead if she remembered “farfar” (grampa) and she said “he lives far far away”). I’m sure this psychosis has affected me in some way.

BB: Do you consider your work political?

JG: Yes, all writing is political (and pig shit). But my writing is not a “critique.” I don’t relate to the prevailing ideal of “critical distance” in “experimental poetry.” I’m interested in utter saturation, I’m interested in infection. I’m interested in costume dramas and bleeder’s disease.

BB: I wonder also about the influence of your interest and activity in translation in your work, how the experience of shifting the language of people like Aase Berg and Jönsson and the like ends up affecting the way you think about connecting language in your own writing? Does the act in some way change the way you are wired? Is that act of translating political in another kind of way from writing itself?

JG: This is something I have thought about a great deal. American writers/readers are so troubled by translation: it’s inauthentic, counterfeit, kitsch. They want the real thing, not this fake, possibly pathological thing that foreigners peddle. Part of being an immigrant is being suspect, part of translating is the same suspicions. We’re cheaters, we’re not quite real. I’ve been repeatedly accused of making up the poets I translate (I take it as a compliment!). But then I’ve also been suspected of fucking Lara Glenum. We’re pathological agents, foreigners and translators, treasonous kitsch-makers with unofficial access to jouissance. One way of solving this problem is not to read things in translation (very common); or to see it as a necessarily flawed imitation but necessarily good for you; or to focus on interlingual writing. The last one is seductive indeed, and in part I have participated in this answer: in a lot of my works there are interlingual puns or auto-translations (in a variety of ways – homophonic, stutttery, infected, bled-out etc, all very technical terms), especially in my book Pilot (“Johann the Carousel Horse”), which aims to create a kind of leaky in-between language that sounds like partly a backwards-tape that drags and partly like Swedish and partly like English. I get all spassy when I read it, so I don’t read it very often, but it’s more like a performance piece, something that needs to be read (as Stina Kajaso just wrote on her blog “performance” really basically means “show your tits!”); I want to hear English as a foreign language. The problem is when such interlingualism becomes an excuse not to deal with foreign lit in translation, and more importantly, a way of dealing with foreign languages that does away with the scandalous counterfeit nature of translation. I don’t want to remove that. That’s the politics of translation in a nutshell.

JG: This is something I have thought about a great deal. American writers/readers are so troubled by translation: it’s inauthentic, counterfeit, kitsch. They want the real thing, not this fake, possibly pathological thing that foreigners peddle. Part of being an immigrant is being suspect, part of translating is the same suspicions. We’re cheaters, we’re not quite real. I’ve been repeatedly accused of making up the poets I translate (I take it as a compliment!). But then I’ve also been suspected of fucking Lara Glenum. We’re pathological agents, foreigners and translators, treasonous kitsch-makers with unofficial access to jouissance. One way of solving this problem is not to read things in translation (very common); or to see it as a necessarily flawed imitation but necessarily good for you; or to focus on interlingual writing. The last one is seductive indeed, and in part I have participated in this answer: in a lot of my works there are interlingual puns or auto-translations (in a variety of ways – homophonic, stutttery, infected, bled-out etc, all very technical terms), especially in my book Pilot (“Johann the Carousel Horse”), which aims to create a kind of leaky in-between language that sounds like partly a backwards-tape that drags and partly like Swedish and partly like English. I get all spassy when I read it, so I don’t read it very often, but it’s more like a performance piece, something that needs to be read (as Stina Kajaso just wrote on her blog “performance” really basically means “show your tits!”); I want to hear English as a foreign language. The problem is when such interlingualism becomes an excuse not to deal with foreign lit in translation, and more importantly, a way of dealing with foreign languages that does away with the scandalous counterfeit nature of translation. I don’t want to remove that. That’s the politics of translation in a nutshell.

BB: What are you working on now?

JG: A murder mystery novel/poem/notebook about Images and infection, atrocity kitsch and The Law. A Starlet has been murdered, terrorist attacks happen, children are born and get pregnant in mysterious fashion (constantly multiplying), the son is locked in a tower with his favorite horse toy, the penis is a death prong through which – on the ouiji board – the murdered children of the Vietnam War finally gets to “speak,” they talk about the mall and the law, there are twitter feeds about motorcyclists who come from the castle outside of town, terror suspects who are given rubber gloves and led through the mirror, “Kingdom of Rats” it says above the mirror, it’s all about photography, hares, the body in snow, the body covered by a plastic bag, Art as Death. Etc. It’s always a staging, a pageantry, a b-movie. I hope that gives you some idea. I’m calling it The Sugar Book.

I’m also working on a staging of The Duchess of Malfi. Back in the day a girlfriend and I made a video version of The Duchess of Malfi which we shot at a shooting range (she was into guns and knew the manager). “The Ouch-Ouch” we called it. I want to go back into that space – the shooting range, the wax sculptures – but I want to pay even more attention to the clothes, the seams. I want the movements to be more exact this time.

* * *

Johannes’s most recent book, Entrance to a colonial pageant in which we all begin to intricate, is available now from Tarpaulin Sky.

Tags: aase berg, Johan Jonsson, Johannes Göransson, tarpaulin sky

[…] by Johannes on Jun.02, 2011, under Uncategorized You can read the whole thing here. […]

Sign me up for The Sugar Book.

this guy is unreal.

Good interview.

holy cow, why have i not actually read any goransson outside of montevidayo? i’m going home and reading entrance… stat. also, The Sugar Book sounds like basically the best thing ever.

Holy shit. What a feast; I’m too full, coming up at the mouth. Thanks guys.

ta.gg/55j

http://tld30.com/?UQHAvj

http://tld30.com/?UQHAvj

ta.gg/55j

” I am playing the race card with a revolver pointing to my head. The revolver has an autonomic system. It is loaded with two silver bullets: one for my black brain and one for my insect nerve.” – jg

hot

It’s grrrreat! Especially the bit about “costume dramas and bleeder’s disease”! And pretty much the whole rest of it too yall.

“I want to hear English as a foreign language.”Just realized (had put into words) that this is a daily experience for me.

All of a sudden I feel profoundly anti-translation.

Translation fails.

It is treating someone else’s words like a hunk of soft warm dough to put in your own oven when they are in fact a very sturdy punching bag or a sack of mylar confetti.

ta.gg/55j

shiiiiiiit. how do you come up with better back cover copy for the sugar book than that manic, spazzed out description in this interview? impossible. i can’t wait for that.

to the people saying they haven’t read any johannes books–i’ve read them all and a few of the translations, but i feel like nothing could have prepared me for this last book, the pageant so let me put that suggestion out there. i just finished up a review of it and it was intense getting to spend so much time with it, getting so close with it. i was in some sort of violent, phantasmagorical matrix. it was an experience…just reading the book makes you feel like a shaman, like you’re conjuring up the devil, but better, because it’s you.

johannes, you’re a pyrofield. Sinead is, too.

way to know your shit, blake. big thanks for this.

[…] crap. Blake Butler, whom I love, interviewed Johannes Göransson at HTML GIANT. One great thing about the interview: it starts with this […]

I took that photo!

Also, great interview, y’all.

Where d’ya buy the acid, man? Gimme some of it, but only half as much…

[…] rioted body.” For a noise act in Tokyo, I took a cheap white shirt, a shirt and smeared it–dirtied it red, made it better. The photographs that were taken on the were tinted in the screams and shrieks, […]

[…] Read the full review. […]

[…] Read the full review. […]

[…] This is a book I’ve been writing for years – in South Bend, in Seoul, in Malmö, in Berlin. I wrote this in an interview from 4 years ago when Blake Butler asked me what I was working on: […]

[…] You can read the whole thing here. […]

[…] Read the full review. […]