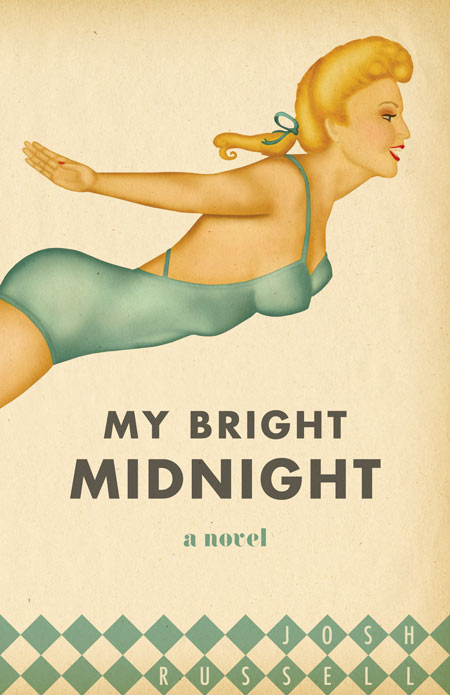

The risk, lyricism, and page-turning plot of Josh Russell’s Yellow Jack appear again with maturity and elegance in his second novel of historical fiction, My Bright Midnight. How? Why? With what nerve? Josh Russell, recipient of a National Endowment for the Arts Literature Fellowship and Co-Director of Georgia State University’s Creative Writing Program, reveals a secret or two.

Q: Aimee Bender wrote, “Everything a human experiences happens on the body. That’s enough setting for me.” Your protagonist Walter is very self-consciously embodied after leaving Germany and experiencing life in 1930’s and 40’s New Orleans, which you imbue with its own highly sensual body. Would you discuss the way the settings (or bodies) worked together in your process of writing the novel?

Q: Aimee Bender wrote, “Everything a human experiences happens on the body. That’s enough setting for me.” Your protagonist Walter is very self-consciously embodied after leaving Germany and experiencing life in 1930’s and 40’s New Orleans, which you imbue with its own highly sensual body. Would you discuss the way the settings (or bodies) worked together in your process of writing the novel?

A: A few days ago I was commiserating with a friend about commuting and how we both missed being able to walk to work, and I was amused and amazed to realize how related writing and walking are for me. I wrote Yellow Jack while walking during two years of lunch hours when I was working as a help desk dispatcher: Walk a few yards along the path beside Boulder Creek, stop, write a sentence in my notebook. Walk a few more yards, stop, write two sentences. I would have had a lot less to write about had I not spent so much time walking to and from work when I lived in New Orleans a few years before I began even thinking about Yellow Jack. My Bright Midnight comes in large part from my second, longer, residence in New Orleans, during which I regularly walked the twenty-odd blocks of Magazine Street between my house and Tulane University, where I was working, stopping to buy pain raisin at the neighborhood boulangerie, cafe au lait at the coffee shop, and blood oranges at Whole Foods (it’s amazing to recall that this did not seem in the least pretentious). Obviously the New Orleans landscape is an important part of both books. As for how settings and bodies worked in my process of writing My Bright Midnight, when I choose to write something with an historical setting, I do so in part because of the challenges of avoiding clichés about the past, and one strategy I employ to answer those challenges is to make sure that the characters’ interiors and exteriors are never lazily constructed.

Q: Why did you choose a first-person narrator, and one like Walter?

A: Another of the challenges of writing fiction with an historical setting is avoiding narrators who sound as if they’ve escaped from a Ken Burns documentary. First person makes it harder for them to speak like Morgan Freeman reading a script. More seriously, my investment in this genre of fiction has to do with giving voice to the kinds of people history has a tendency either to silence or to treat with infantilizing condescension, so I usually go with first person. I hope when you ask why “one like Walter” that you mean a narrator who is articulate but flawed. If so, then I like those kinds of narrators because I like those kinds of people, and I like to meet them in books as well as in real life.

Q: “I drank gallons of inky coffee laced with chicory and sweetened with the powdered sugar I shook off fried doughnuts. For dinner my landlady served fried eggplant smothered in red gravy, bell peppers stuffed with chop meat, artichokes stuffed with seafood and breadcrumbs. I ate it all, then somehow I found more room and kept eating—spearmint snowballs with condensed milk, Russian Cake, apple fried pies.” True to the city, you include a lot of its food. Did you get hungry writing this book? If so, what did you do about it?

A: I wrote much of the book while not in New Orleans, so a lot of the mooning over food was a way for me to remember things I loved about the city—things that made me fat. What did I do about it? Ah, well, what can you do? I learned to be a better cook.

Q: Like its title, My Bright Midnight is lyrically cadenced—“Esther stood naked and grinning in the brilliant sunlight, waves covering and uncovering her like pale blue veils”—and the book is in part about language and belonging. How did those elements shape the novel?

A: I was a sloppy speaker until I became a careful writer (in college), and then I became a fussy, twee speaker. I was probably twenty years old when I started to see how careful attention to diction could make “simple” language lyrical. Walter’s a careful speaker in part because he’s a guy who values precision, in part because he’s an immigrant, and when his wife seems to claim that she’s been unfaithful because he can’t speak English like a native, he makes sure every description is perfect. I hate the idea of “transparent prose.” I read to see what happens, and to enjoy language; I don’t write just to offer up plots and characters, but to make interesting prose.

Q: Recently you told Bob Edwards in an interview that writing about places where you aren’t currently living allows you to focus on detail that will serve your fiction rather than overtake or factually exhaust it. Since your first two novels are historical fiction, do you find writing about a different time liberating in similar ways?

A: Yes. In both cases distance allows me to sort things out, to decide what’s most important, and to make things up more easily because I am not overwhelmed by entire landscapes, or limited by facts.

Q: You managed to write two books, rear a baby, and mentor graduate students at the same time. Are you Faust? What kind of discipline and inspirations were at work here or remain at work for you in general?

A: When I was working answering phones, I decided that I had to decide who I was: A guy who answered phones and wrote fiction as a hobby, or a writer who answered phones so he could pay the rent, and if I chose the latter, I needed to write every single day. I chose the latter, and then taught myself to be able to write whenever I had the time, even if I didn’t feel “inspired.” That training was the most important breakthrough as a writer I have ever managed. It proved to me that I could make art when I wanted to, not just when the muse struck. I’m now revising a book, not writing a new one, so I’m not writing as much as I would be were I working on a new project. When I’m working on something new, I try to write two or three pages a day. If that takes thirty minutes, good for me, more time to cook or wash dishes or send email. If it takes three hours, well, ouch. And I never write fiction for more than three hours a day. Doing so exhausts me and leads to sloppy and/or manic work.

Q: You always say, “It’s not the experimental form; it’s the experimental idea.” How do you see this working in your own writing, whether short or long form?

A: It’s a way of reminding myself not to become too enamored with form, especially quirky form, while also being sure not to abandon my desire to make something new, to experiment. Pretty much everything I write follows this dictum. I’m always trying to take an idea that seems objectively wrong, or impossible, or stupid as the subject of fiction and make it a subjective success.

Q: Where can we read more Josh Russell? What are your current projects?

A: I have a novel forthcoming in 2012 from Dzanc Books: A True History of the Captivation, Transport to Strange Lands, & Deliverance of Hannah Guttentag. I’m also writing stories, some very short (as short as a single sentence) that I’ve been publishing in literary magazines (most recently Epoch and Copper Nickel). I have a thirteen-story collection of these very short stories. Alas, it’s 28 pages long, and there’s not much interest in a 28-page story collection. I’m adding stories to it, though, so maybe someday soon it will hit 30 pages.

* * *

My Bright Midnight is available now.

[Fiction by Lydia Ship has recently appeared or is forthcoming in American Short Fiction, Hobart, Night Train, Staccato, PANK, Pindeldyboz, Quick Fiction, and Requited Journal. She is a former student of Russell and Contributing Editor at The Chattahoochee Review.]

Tags: Josh Russell, Lydia Ship, My Bright Midnight, Yellow Jack

I like this: “It’s not the experimental form; it’s the experimental idea.” Great interview.

Good interview. Glad I made it past “A few days ago I was commiserating…”.

Told you I was twee: I commiserate, I pontificate. But I can go monosyllabic when necessary.

yeah yeah, I’m buying it right now. Jesus.

Fantastic professor. New book is great.

Ha! And here I was, just cracking wise. Seriously: Just having fun.