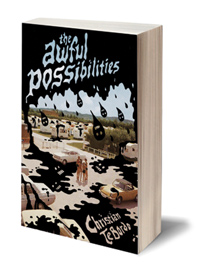

In the summer of last year, Featherproof released The Awful Possibilities, the fourth book by Philadelphia’s Christian TeBordo. It is an assemblage of extreme range in sound and direction, as TeBordo’s work manages to funnel a kind of well-orchestrated, rising mania across a range of perspectives and situations, including teenage suburban thug rappers planning a school shooting, a logic-fucked woman involved in shady black market business in a hotel, a dude trying to buy a new wallet, deathbed advice minds, and several other hybrid enactments than in other hands would lack the flair of TeBordo’s ability to funnel livelanguage and feeling into seemingly any kind of body. As says George Saunders: “Christian TeBordo shows that it is possible to be, simultaneously, a wise old soul and a crazed young terror.”

In the summer of last year, Featherproof released The Awful Possibilities, the fourth book by Philadelphia’s Christian TeBordo. It is an assemblage of extreme range in sound and direction, as TeBordo’s work manages to funnel a kind of well-orchestrated, rising mania across a range of perspectives and situations, including teenage suburban thug rappers planning a school shooting, a logic-fucked woman involved in shady black market business in a hotel, a dude trying to buy a new wallet, deathbed advice minds, and several other hybrid enactments than in other hands would lack the flair of TeBordo’s ability to funnel livelanguage and feeling into seemingly any kind of body. As says George Saunders: “Christian TeBordo shows that it is possible to be, simultaneously, a wise old soul and a crazed young terror.”

Last month, Christian and I took some time emailing about the book, Christian’s experience of influence by Brian Evenson and others, the process of assembling a text, getting along in sound and structure, approach, revision, and nudie pics.

* * *

BB: The Awful Possibilities is your first collection of short fiction after having published three novels. Do you see yourself more as a novelist, and is there a difference in your approach? Were these stories written over a long period of time?

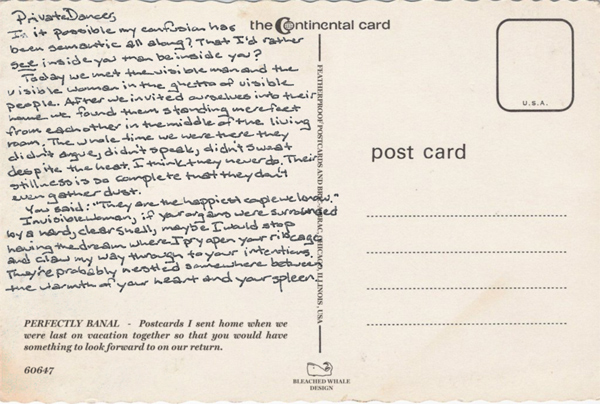

CT: Let me answer these backwards, because that way it goes from easy to really hard. The stories in The Awful Possibilities were written over a little more than 10 years. One of the stories in there is the first I ever made that I considered a story. The most recent (the postcards), I sent to featherproof after they’d accepted the manuscript. Actually just before the book got laid out. I wrote and published my three novels during the same time. I don’t approach the forms differently when I sit down to write. For me it’s just the sentences and the persona that generates the sentences telling the larger work where to go. On the other hand, I try to do something different each time. People who read my last novel might recognize a sensibility or tendencies in The Awful Possibilities, but I hope nobody would be able to predict what one would be like having read only the other. The question of how I see myself is a little tougher. As a writer, I’m happy doing both. Stories are fun because sometimes you can just bulldoze through a draft in a sitting or two. Or you can spend weeks being really meticulous and crafty with a few paragraphs without getting disgusted by what you’re up to. Novels are fun because you have some sense of what you’re going back to each night and there’s more room to surprise yourself. The truth is, though, I feel more comfortable with short stories because I do want to be read, but I want my stuff to be an all-out assault, too, for now at least. I think people are more willing to put up with that for 10 pages than 200.

BB: I think you definitely succeed here in shifting prediction: each story in the book seemed to reinvent itself in both approach and tone, and by that I don’t mean form and voice, but more a way of coming into a way of speaking. There is the sense of discovery at both ends, as if the creator on the other end isn’t dictating some endless idea, but is worming out of a consideration or into a consideration, elucidating in itself in its moment, if that makes sense. It’s interesting that the stories came out over ten years, as there is also that same kind of continuity in the overall structure of the stories as a whole, I felt: that in their constant reapproaching they are able to more quickly and with more surprising depth a kind of overall world, the body of the book. Do your stories most often come out from sounds, ideas, songs, images? How much of this is a product of obsession and/or revision?

CT: First, thanks for saying that the shifts in the stories succeed. I’m taking it as an observation rather than a compliment (though I’m happy to take it as a compliment, too), because the more people respond to this book, the more I’m realizing that the perceived success of the book as a whole, and any individual story, seems to rest on whether people buy into them (the shifts).

CT: First, thanks for saying that the shifts in the stories succeed. I’m taking it as an observation rather than a compliment (though I’m happy to take it as a compliment, too), because the more people respond to this book, the more I’m realizing that the perceived success of the book as a whole, and any individual story, seems to rest on whether people buy into them (the shifts).

Which brings me to your question: is it too obvious if I say the stories come out of sentences? That might seem unimaginative, but look — sentences can include sounds, ideas, songs, and images. For me the sound aspect is the most important. But once you’ve written that first good-sounding sentence, you’ve eliminated a lot of the possibilities for the second. Once you write the second, and you think it sounds good, too, you’ve kind of bound yourself up. By the third, your only job is to make sure it keeps sounding good and you don’t get bored. You know who’s saying the sentences and you know what that person would or wouldn’t, could or couldn’t say. It’s not always conventionally beautiful or grammatically elegant, but you’re trying to make a certain kind of beauty arise from the context, which is the art of it.

So, yeah, sentences encompass all of the aspects you mentioned. Except ideas, I think. I wouldn’t be able to say to myself: I want to write a story that explains my take on ethical interiority. Or: it’s time for me to write that story about race. At the same time, I think and hope my honest take on those issues will come out as the sentences do.

Obsession and revision — it depends on the story. I definitely get obsessed with my own work, but I’m not one of these folks who get doctrinaire about revision. Revision can be the most important part of the process for a particular piece of writing. But it isn’t the most important part of writing. Professors invented that claim so they’d have an excuse to charge bad writers tuition. (Love you professors; sorry bad writers.) Ever since computers, first drafts are only first drafts when they’re written by hand. (I mostly write by hand.)

This all sounds really abstract, so maybe I should use examples?

Probably the most obvious from my book is “Moldering.” The first line is: “I was growing moldy of wallet from hoeing down and the sweat therefrom.” To me that sounds like a pretentious take on a mildly-gross subject. It came out of me joking around with myself when my own wallet got a little stank from dancing one summer. I got the sentence in my head just walking around thinking about how I needed a new wallet and why. I was making fun of myself, but I also started thinking of it as a kind of pastiche of Brian Evenson (one of my favorite writers and probably the closest I ever came to having a mentor), who often applies high/grandiose diction to low situations. As soon as I started writing, I knew what the narrator was going to end up doing. To me it’s the only real logical conclusion.

As a negative example, I’m going to risk getting my writer card revoked. I love David Foster Wallace, and I think his stories are just as important and innovative as Infinite Jest. I go back to the first two collections all the time, and they’re probably the best examples I could come up with of what I want from a book of stories, which is a willingness to try anything. But sometimes I question his follow-through. “Girl With Curious Hair” is an amazing aesthetic accomplishment, but that passage toward the end, where we find out that the narrator got his dick burned by his too-intense Marine dad, is a copout. It tries to suggest that that’s why he is the way he is, when if he were real, it would be ridiculous to give a single reason why he is the way he is. I think people tend to accept these kinds of explanations as a way of dodging the awful possibilities (hence the title of my book) of being human.

It’s not unlike how, when a celebrity gets caught texting naked pictures, he or she goes to rehab, and people accept that, even though alcoholism doesn’t actually explain it. Maybe they think it’s more palatable than a world where everybody feels comfortable sending complete strangers naked pictures.

There’s beauty in the awful. What I mean by that is, please send n00dz. Blake has my address.

BB: RE: ideas & revision, in context of the Wallace detail, do you find yourself ever catching yourself in the midst of an idea that is defuncting? Like, your narratives definitely have this kind of sporadic but of a certain mind feel to them. I wonder how an author might catch his or her self in the moment of that wrong cue, and how to stop and find the right way in the moment of inspiration? I’m thinking particularly here about your story “The Champion of Forgetting,” the voice of which is so astounding, and it seems like almost anything could have happened as long as the voice stayed true to itself. This makes me wonder how you know which mode is the right mode: is it about feel, during the writing? Evenson is indeed a master of this, having that energy that functions into such surprising ends that you can tell have not been over-orchestrated. Maybe there is something specific you could outlay in learning from him?

CT: I’d like to think I’ve gotten to the point where I can trust myself to “stop and find the right way” sooner or later, but I have to admit I’m not particularly good at stopping my self “in the moment of that wrong cue.” I think all writers have that mystical feeling when a good story seems to almost physically descend on our heads and we feel like if we could just get it all out at once, not, like, in one sitting, consecutively, but every word at the same time, like the print equivalent of a photograph, it would be absolutely perfect. Though come to think of it, I don’t think I’ve ever asked any other writers if they feel that way. In any case, I get that feeling all the time (I don’t bother starting a story without it), and of course, it never works out perfectly.

“The Champion of Forgetting” is a case where I did work straight through a story, but I did it over the course of a couple years. What happened was I was sitting in a McDonald’s in Syracuse, NY, and there was a woman in there talking in this strange monotone that didn’t seem to have any punctuation but periods in it. Even though it was a monotone, she sounded more viscerally sad than apathetic, and I jotted down some of the things she said. When I got home, I kept it going, and it was a fairly easy voice for me to maintain because it had enough idiosyncrasy that I could focus on the rhythms rather than how miserable she sounded. After about a page, I stopped, for two reasons. One was that it felt like it was going too easily (at the time I was using a lot of constraints — I’ll get to that in a second) and the other was that the pieces were adding up to organ thievery, which just seemed too nu metal to me. I put it in a folder and forgot about it.

A couple years later I was living in Philadelphia. I’d been blocked for over a year, plus the reviews for my first novel were starting to show up in places I hadn’t expected to get attention (Kirkus, Publishers Weekly) because I was working with a really tiny micropress. Pretty much everybody hated it. It was kind of an absurdist noir, but written with some very “brainy” methods. I was crushed because I was young and I thought (and still think) it was a good book. So I was going through my folders and found the page I’d written. I wrote “Here is a list of failures” at the top, and otherwise started exactly where I’d left off. There was a petty revenge aspect to it, like, all right, let’s show them what happens when I turn off my brain and write with my gut. As though anyone cared (although assuming no one cares is also liberating).

You’re right that “anything could have happened as long as the voice stayed true to itself,” and this might be where the obsession that you asked about earlier comes in. Once I got it in my head that the lady in McDonald’s was talking about organ thievery, it was either write about organ thievery or don’t write the story. (I should mention that the topic doesn’t seem shocking or fantastic to me. I grew up the son of two ministers in an economically depressed rustbelt city, so my version of naturalism might be skewed. Or everyone else’s is.) I finished it fast and no one has called me nu metal yet.

I could contrast that with a story like “SS Attacks!” which was an assignment from the Lifted Brow. That one I spent months of false starts trying to do it in a third person minimalist voice. Finally, a week before it was due, the first line came to me. The voice sounded like a blog entry from a relatively intelligent backpacker (as in early 00s rap, not Lonely Planet), so I just plowed through in a sitting using way too many syllables, tons of internal rhyme, and words like “imagine” and “remember” for the hooks. Easy once I hit it, but the hardest story I ever wrote if you count how far I got into the first few drafts. And that’s the last proper story (as opposed to the postcards) I put in the collection. So yeah, I know what’s wrong, but it can take a long time to find what’s right.

As for Evenson, I don’t know if I could express how much I learned from him. Almost any one of his stories is an example of the value of following the narrative where it needs to go (rather than where it’s most comfortable, or to some pretty epiphany about the essential goodness of even the darkest people). The critical and public response to his work suggests to me that, if you allow yourself to grow as a writer while being honest with yourself about the work, people will eventually be willing to read you on your own terms. And as a person, he was always willing to approach my work from my perspective and show me how to make it better (as opposed to dismissing me, or worse, blowing sunshine up my ass). I also like how he writes fucked up shit and is still a really thoughtful, considerate dude. During the semester he was at Syracuse, people would go to him for all kinds of life advice that had nothing to do with writing.

Writing about Evenson here reminds me of something I wanted to ask you based on your first question. I think I see an Evenson influence in your work, but I think we take very different lessons from him. Maybe we’re both as concerned as he seems to be with tone, but where I use it to push a story forward as fast (velocity, not composition time) as I can, you seem much more comfortable creating atmosphere with fragments, imagery, and a lot of Germanic roots. Because of this, generic distinctions (novel, novella, short story, even prose poem) don’t seem to apply as much to your stuff. Do you make these distinctions when you write? I ask, because, like I mentioned before, I seem to get different reactions based on how I present things, and also because I personally find Evenson’s short stories to be much more successful than his novels (Dark Property excepted).

BB: That’s an interesting distinction. I like the idea of atmopshere in writing, in that sometimes a mood or a way of speaking I think can propel a text forward with velocity even if nothing in particular seems to be happening; this is definitely something Evenson’s prowess in influenced me with, such as in his story ‘Two Brothers’: that story is so mood and image; things happen, but they kind of become shattered and the shards then can move forward in affect or feeling, inside the reader, even if the subject isn’t necessarily sure of itself inside itself. The biggest moments with Evenson, for me, are ones where he seems to invoke this kind of second layer, behind even what the narrator or voice says it is doing, or what it thinks it is doing, and more this like thing behind the thing. I think Robbe-Grillet was a big influence on Evenson in this way, and some of his books are all that kind of ‘talking about the thing without talking about the thing,’ which for me has always caused the greatest amount of fear. Fear is most powerful when you don’t know exactly what you’re fearing, because then you are defenseless. Evenson definitely taught me by scaring the crap out of me with things he didn’t even say, but circled around, and that to me is a real invocation of power.

I definitely see what you mean about your writing being concerned with velocity; the voice seems manic almost, often, but also in a funny, ‘get me there’ kind of way, which interests me a lot: did this come out of some organic tendency in your practice, a method of how you approach being at the desk? What other writers or books in particular were instructive to you learning how to write, or made you want to write at all in the first place?

CT: It’s interesting that you’re asking about influences at the same time as you mention affect and effect, especially with regard to this risk that the reader might miss what I’m aiming for by reading strictly for story’s sake at the speed the stories are written. I guess I knew even before I put the book out that it wasn’t just a risk but a likelihood. Actually I knew it when I was still an undergrad and I workshopped what would become the story “Took and Lost.” I handed it in under the title “A Relation of How the Man Who Lost Something Reacted to Losing Something,” and in the end, there was a mention that the man who took something was chewing gum as he walked away. Earlier on the narrator points out that the man who lost something had a pack of gum in his pocket. So some of the kids in the workshop said they liked the story but they didn’t think it should all be about a piece of gum. I had put the gum in there under the influence of Nabokov. I don’t think he was all that into gum, but I loved how he would repeat images, slightly altered, at different places in a book for what seemed like fun.

But the story wasn’t about gum. I’d meant it to be about how we generate meaning by interacting with each other. So when I went back to edit it (again, a few years later), I took out the line about the gum, struck a lot of adverbs and other British-y sounding language that I’d put in there because I was young, changed the title, and that was about it. I can’t be sure that people are going to read it the way I want them to now, but there’s a certain point where I draw the line. It’s intuitive. I’ll take out the red herring if it seems like a real obstruction, but I’m not going to come out and say: “That was when the man who lost something realized that, whatever the man who took something had taken, he’d also taken his sense of life’s absurdity.” Because people don’t really have realizations like that. Or they do, but they have no effect on the way they’re living five minutes later.

I guess what I mean is, while I’d like to think that Nabokov, Flannery O’Connor, Barthelme, Padgett Powell, Barry Hannah, and to some extent Stein, Beckett, and Babel are influences (and they are as far as I can point to them and say “this is what inspired this” or “I was reading this when I thought of this”), the truth is, a weird form of ghetto Calvinism got to me before I ever heard of any of them. The Awful Possibilities probably owes as much to my parents’ sermons and Kierkegaard’s Either/Or as it does to any work of fiction.

Anyway, it’s okay with me however anybody wants to read it now that it’s out. But I’ll buy you a beer if you want to talk Kierkegaard.

BB: Those kinds of cross overs of the expectation of a direct punch coming out of the swing instead of seeing the swing kill me. I don’t know exactly where people learned to read that way, perhaps some amalgam of boring reading lists and responses in high school, mixed with narrative television and pop crap, but I expect that that kill of the mystery and the formality of how a story is told is a big part of the reason why reading is less prevalent in general than it used to be, or why it seems marginalized, or people don’t seem to give it the time.

Does the way you read aloud come into play when you type this way? Do you feel like you are influenced by your surroundings: film, music, people talking? I’m wondering about how sound fits into an idea; so many people start with the idea and try to make the sound fit (or ignore sound), while others go so hard on sound they miss ideas; you seem, like Evenson, a fuse of the two, but also in some ways totally different than Evenson. Maybe Saunders, who I know you studied with, played a big role? And in general: how did you go about structuring the order of the stories?

CT: Both Saunders and Evenson had a big effect on the way I read aloud, but in indirect ways. I’ve always liked performing — I was in hardcore bands throughout high school and did a lot of freestyle rap shows in college — but I never liked reading in public. Maybe because performance was so tied to a kind of violence (the former) and improvisation (the latter), I always thought of being on stage as a chance for catharsis as opposed to the conscious crafting (even when it might seem out of control) that I’m aiming for with fiction.

It was in grad school, where I studied with both Evenson and Saunders, that I had to start thinking about how to get some of that energy into the readings, because we were strongly encouraged to read aloud — it was even a part of our graduation ceremony.

Anyway, Evenson and Saunders are both excellent readers, but I noticed that Evenson’s characters sounded totally different in his mouth than I’d heard them on the page, while Saunders’s sounded exactly like I read them. The risk in going the Evenson route is creating too much dissonance between the performance and the words on the page. The risk with Saunders is that you could write with you’re speaking voice too much in mind. If you’re really opening up, there are things that you can say on paper that you can’t say convincingly with your own tongue.

My solution was basically to accept that there are things that I write that I can read well aloud and things I can’t. I can rock “SS Attacks!” or the postcards, but I’ll probably never have the guts to attempt “The Champion of Forgetting” at a reading, even though it’s among my favorites. It’s not about the quality of the stories; it’s just what my voice is capable of.

But yeah, it’s pretty much limited to sound. I spend a lot of time thinking about the way people talk, and also music, in strict and broad senses, but I’m not a very visual person. I watch movies and sometimes get inspired by them, but what I steal is pacing and rhythm. Even imagery becomes voice. I basically see rhetorically.

I wish I could take credit, but Jonathan from featherproof put the stories in their final order. When I saw it, I realized he was dead on, but it made me realize there was something missing. I asked if we could include the postcards, and Zach made up the idea of getting all design-y with them. Those guys are brilliant.

BB: What are you working on now? What’s next?

CT: I finished a novel a while back and I’ve been sending it around. That will probably be the last one for a minute because I’ve got a four month old son. We spend a lot of time making faces at each other and chanting “who? who? who?” Then we stare longingly at his mom/my wife. I’m trying to turn him on to theoretical physics and basketball because I have a feeling basketball-playing scientists really get a lot out of life. Otherwise I’m doing short stories — mostly Ayn Rand fan fiction — and my treatise on love.

* * *

The Awful Possibilities is available now from Featherproof Books.

Tags: Christian TeBordo, featherproof, The Awful Possibilities

Good interview. Christian TeBordo is a good writer.

Love Christian! Awesome interview

Christian is O.K., you spelled “atmosphere” incorrectly…

b2cshop.us

love-shopping.org

madeshopping.net

supershops.org=

b2cshop.us

b2cshop.us

b2cshop.us

[…] we forget either of those important points, Christian did an interview with Blake Butler of HTML Giant where he says lots of things that remind me of why I used to try […]