I Like __ A Lot

His Geography: The Collected Works of Michael Ondaatje

A. “There are stories the man recites quietly into the room which slip from level to level like a hawk.”

The English Patient

1. A popular mistake about Canada is that it is fundamentally North. Otto Friedrich’s biography of Glenn Gould compares Canada’s relationship to the North with America’s to the West, except there’s no Disneyland in the Arctic. Most of Canada’s population is concentrated in the southernmost quarters; post-Gould Toronto produced Petra Collins’ Instagram, among a lot of other non-Drizzy things. One quarter of all postwar immigrants to Canada came to Toronto. Canada’s history is only one centennial in; its youth relative to the rest of the world may account for why the rest of the world sometimes acts so strange about it. Cats still aren’t sure about humans because in evolutionary terms they haven’t been around as long as dogs and are still socializing themselves. There are no cats in the Bible, for instance.

2. The book of 2014, nonfic anyway, was Capital in the 21st Century by Thomas Piketty, a book carrying the mythical glow of pregnancy. Stephen Marche reviewed it for the Los Angeles Review of Books, calling it ‘perhaps the only major work of economics that could reasonably be mistaken for a work of literary criticism.’ He relates realism’s utter defeat of the other forms, the fun ones like lyricism or even minimalism, and credits Jonathan Franzen, that old serpent, with its proliferation. We already knew all that. One of the writers Marche suggests has fallen out of usage is the Canadian Michael Ondaatje: from Ontario by way of Sri Lanka, educated in England, known for hushed, haunted pieces like The English Patient (1992), Divisadero (2007) and The Collected Works Of Billy The Kid (1970). He also wrote a memoir, Running In The Family (1979), which includes the following clip:

“At St. Thomas’ College Boy School I had written ‘lines’ as punishment. A hundred and fifty times. [fragment in Sinhalese] I must not throw coconuts off the roof of Cobblestone House. [fragment in Sinhalese] We must not urinate again on Father Barnabus’ tires. A communal protest this time, the first of my socialist tendencies. The idiot phrases moved east across the page as if searching for longitude and story, some meaning or grace that would occur blazing after so much writing. For years I thought literature was punishment, simply a parade ground. The only freedom writing brought was as the author of rude expressions on walls and desks.”

3. Ondaatje’s family is Dutch-Ceylonese and was well-off. By various vagaries his father ended up a chicken farmer, his mother on staff at a hotel, and he and his siblings diffused thru England, America, and Canada. Much of his writing is liminal: the act of falling on a map, and why is it called falling? ‘We are the real countries’, vows a character in The English Patient. Disdain for colonialism and its legacies is a chief Ondaatje engine; another character in The English Patient insists that everyone white is motivationally English: ‘when you are bombing brown races you are an Englishman’. That character’s name is Kim and he’s Sikh, which we know because he wears a turban. Almasy, the sophisticated count burned into patienthood if not Englishness, is Hungarian but nomadic. He hates ownership, being owned—and the idea that when there’s a war on, where you’re from becomes important.

Ondaatje produces fantasias of language, requiring much suspension of disbelief, risking collapse if pulled too far out of context. As stated by Pico Eyer in an essay for the New York Review of Books called ‘A New Kind of Mongrel Fiction’: ‘ there will always be some for whom Ondaatje is too rarefied or exquisite.’ Lines like ‘giraffes of fame’ and little leashes of them like ‘later my hands cracked in love juice/fingers paralyzed by it arthritic/these beautiful fingers I couldnt [sic] move/faster than a crippled witch now’ qualify as sentimental dithering to the worst agnostics. Glenn Gould said he believed in God as long as it was Bach’s; I believe in a groundless, fermented prose style as long as it is Ondaatje’s. Even when it’s a little bit bad, it is never not beautiful.

‘There is nothing wise about a harbor, but it is real life. It is as sincere as a Singapore cassette. Infinite waters cohabit with flotsam on this side of the breakwater and the luxury liners and Maldive fishing vessels steam out to erase calm sea. Who was I saying goodbye to?’

Ondaatje, Running In The Family

4. Fiction is what the fuck, nonfiction is what the actual fuck. The loose memoir that’s so in vogue, that easy self-deprecating pageflow of major life events and ominous thoughts, is not intrinsically creative. There are thousands of writers in Brooklyn and on the internet, and nearly all of them are sustained by the belief that if they write like they’re on a date, they’ll get a book deal. That belief modifies ‘the fuck’ with ‘actual’ and names style and mood as truth’s opposing co-counsel. ‘A thing is still a thing, no matter what you call it’, Almasy says when told his own writing lacks style. Martin Amis, however, once wrote that “writing, unlike living, is artificial, disinterested: it is not just another facet of reality, however clamorous and incorrigible that reality may sometimes feel.” Let living be punishment, and let writing be the parade ground.

5. Ondaatje’s fictions are the half-lives of what really happened. Almasy and the Cliftons, points of The English Patient’s love triangle, existed as other, dreamed versions. Jazz musician Buddy Bolden stars in Coming Through Slaughter, ‘a morality tale of a talent that debauched itself’. Billy the Kid, in Collected Works, glimmers in archival footage. Ondaatje prints the legend, over and over, copying the original into ensnared loops. Process bleeds from the mouth, research smears the subject until it no longer resembles itself. These altered images, these human shields, are his fashion and weaponry. Ondaatje trained as a poet, not a journalist; for a man who trafficks in the truth, he’s not much interested in it. He knows it’s silly and subjective, transient not trustworthy, and his characters respond to him.

‘The rest of your life a desert of facts. Cut them open and spread them like garbage.’

Coming Through Slaughter

Buddy Bolden was influential in the New Orleans jazz scene at the turn of the last century. A cornetist, he either discovered or developed the Big Four, a syncopated bass drum pattern that further enabled certain improvisations. He neither worked as a barber nor edited a gossip sheet called the Cricket, but a man got to have a trade. Ondaatje includes a sociogram of Bolden’s band members:

[Jimmy Johnson Bolden Willy Cornish Willy Warner

on bass on valve trombone on clarinet

Brock Mumford Frank Lewis

on guitar on clarinet ]

but as pure information it is rinsed beyond belief. By integrating rumors, Ondaatje leaves biography in a pool of its own blood. A blurb for Coming Thru Slaughter compared that novel to a suicide note.

6. Ondaatje detained:

mirrors riffs razorblades cuts cuts bandages themes mirages

7. He likes lists: names, associates, ephemera.

“These are the killed.

(By them)–

Charlie, Tom O’Folliard

Angela D’s split arm,

and Pat Garrettsliced off my head.

Blood a necklace on me all my life”

and

“In Boot Hill there are over 400 graves. It takes the space of

7 acres. There is an elaborate gate but the path keeps to no main route for it tangles

like branches of a tree among the gravestones.300 of the dead in Boot Hill died violently

200 by guns, over 50 by knives

some were pushed under trains–a popular

and overlooked form of murder in the west.

Some from brain haemorrhages[sic] resulting from bar fights

at least 10 killed by barbed wire.In Boot Hill there are only two graves that belong to women

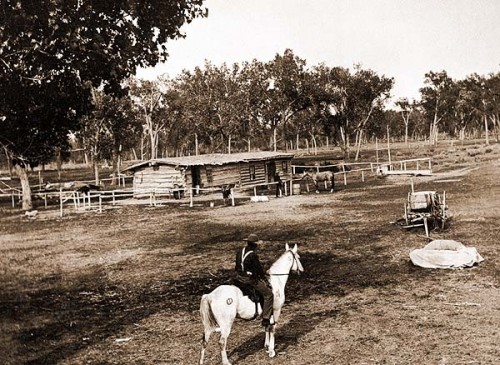

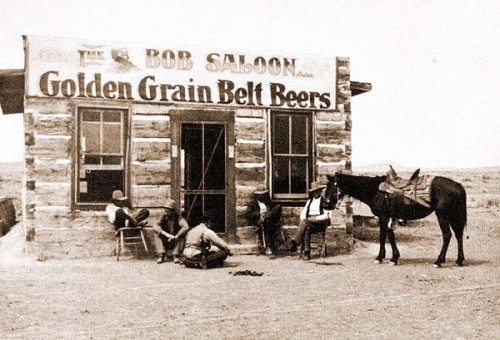

and they are the only known suicides in that graveyard”The Collected Works of Billy The Kid

8. Ondaatje’s most famous work is The English Patient, ‘work’ being operative as its uses are bipartite: Booker Prize-winning novel and Oscar-winning feature film. The latter was a punchline on both Seinfeld and Friends and will thus live forever; those characters in their aggressive normality found its two hours and forty minutes a tedium too far. Meanwhile, the movie outspends the novel in hallucinatory pleasures. The late Anthony Minghella’s filmmaking style may be the perfect alembic for Ondaatje; both his highbrow edit of The Talented Mr. Ripley and the later, sneakier Breaking And Entering outsourced inner heat and light in the same ways.

Reviewing The English Patient in The New Yorker, Anthony Lane called it ‘infected with obsessions’ and ‘entranced by landscape’. Action roils from Tobruk to Cairo to the Italian countryside. Timelines glide by and sometimes glance off each other. War is coming, war is over, war is real-time hell. ‘I don’t know anything’ Juliette Binoche says. Ralph Fiennes, bit of toast, remembers Ralph Fiennes, handsome sphinx. ‘Infected with obsessions’: Ondaatje loves committees, clubs, and societies, all with elegant memberships and prolix means of entry. Almasy is a member of the International Sand Club, a bunch of chaps who study the desert. ‘Entranced by landscape’: the text of The English Patient is laced with the hard data of eremology, presented without comment. Ondaatje’s is not the fundamental desert so feared by Ann Plato:

“In short, to be thirsty in a desert, without water, exposed to the burning sun, without shelter, is the most terrible situation that a man can be placed in, and one of the greatest sufferings that a human being can sustain; the tongue and lips swell; a hollow sound is heard in the ears, which brings on deafness, and the brain appears to grow thick and inflamed.”

Ondaatje, and thus Almasy, knows every wind by its name and search history.

“There is a whirlwind in southern Morocco, the aajej, against which the fellahin defend themselves with knives. There is the africo, which has at times reached into the city of Rome. The alm, a fall wind out of Yugoslavia. The arifi, also christened aref or rifi, which scorches with numerous tongues. These are permanent winds that live in the present tense.”

Deserts are zones of death, but you can cut the heart out of a plant and drink it. Deserts are also where mirages happen: the most desired things you only think you see.

9. Rebecca Solnit stole 2013’s nonfic scene with The Faraway Nearby. Ostensibly a memoir, it vacates immediately into a dazzle of asterisks and flanges, nominating account after account into flawless consideration. Icons like Mary Shelley and Che Guevara are characterized at length but never fully disposed of; their agencies fill even pages that don’t reference them as Solnit rejoices crazily in the frangible. The book’s single most discussible technique is the line of text that crawls left to right across the bottom of each page onto the next, a footer that serves as epigram and eulogy. This melancholy chyron lures the eye with recursive details of moths and legends, Rainer Maria Rilke and the National History Bulletin of the Siam Society. It’s a delirious song of the open tab. Solnit stations both writer and reader at the crossroads of memory and loss. Much of the book concerns her mother’s Alzheimer’s agonies:

“In Alzheimer’s disease the hippocampus is among the areas affected first, that little coil in the central core of the brain that shares a Latin name with sea horses. Shaped like a sea horse, it forms memories.”

Eagle-eyed spotters will notice how much that passage recalls the line early in The English Patient about Almasy’s penis “sleeping like a sea horse.” Almasy’s memories of his towering love affair are both graphic [“I remember her garden, plunging down to the sea. Nothing between you and France.”] and drug-slowed [“wearing these false limbs that morphine promises”]. He is hippocampus squared, prisoner of a dead language. When it comes to brains, nobody knows anything.

In one of her many flourishes, Solnit compares degenerative brain conditions to fairy-tale curses: she notes the French word for ice–glace–can also mean mirror:

“Ice, mirror, glass: the glass coffin in which Snow White lies dormant, poisoned, might as well be made of ice, as though she were frozen like those bodies in cryogenic storage, waiting to be thawed when their disease becomes curable.”

Compare that to a slurred sex scene from Coming Thru Slaughter:

“We give each other a performance, the wound of ice. We imagine audiences and the audiences are each other again and again in the future…As if everything in the world is the history of ice.”

Both writers succeed in othering the real, doctoring a dissociative realm that’s neither here nor there, both fuck and actual.

10. Todd Edwards is a producer of house and garage music who won a Grammy this year for his contribution to Daft Punk’s Random Access Memories. He’s known for cutting up existing vocal samples, often monosyllabic, and creating new pitch-shifted melodies as acts of musical dissection or collage. Sometimes new phrases are created from the old vocals. Making a track or remix involves pulling from 8-12 banks of collected samples, a minimum of 25 per bank, and moving the samples from key to key as needed. Edwards’ originals and remixes move elusively, irrespective of beats per minute. A kind of neuralgia is injected; the reconstituted vocal parts and found chord progressions call out for their missing pieces. Toothache, earache, jaw pain, cheek pain: echoes of lost nerves. Edwards discussed his technique with the blog Little White Earbuds: ‘Making a cut-up track, at least the way I’ve been doing it, is different than working on a regular track ‘cause you’re not just layering piano. I’m actually working from left to right–you’re filling gaps. It’s like you’re putting together puzzle pieces.’ The idiot phrases moved east across the page.

11. Ondaatje’s output has been called ‘verbal cinema’. A book that would qualify as deep Ondaatje is The Conversations, a collection of talks with the film editor Walter Murch. Ondaatje’s juxtapositions and jump cuts do acquire a filmic quality, although it’s not exceptionally visual writing. You are always alert to the text, its arrangement; the sensation of reading is always felt. Murch edited The English Patient;those are his moves as much as Minghella’s. The process of film editing is natural catnip to someone like Ondaatje, who has never stopped writing abt craft as applied to others–bombmakers, bridge-builders, barbers, jazzmen, gamblers.

‘I love the performance of a craft, whether it is modest or mean-spirited, yet I walk away when discussions of it begin – as if one should ask a gravedigger what brand of shovel he uses or whether he prefers to work at noon or in moonlight. I am interested only in the care taken, and those secret rehearsals behind it.’

Divisadero (2007)

In an interview for BOMB, writer/intellectual Guiliana Bruno relates a fascination with film production:

“The film being produced in a factory resembles a sheet of fabric being industrially made. It unfolds continually from a roll, like a thin layer of cloth. There’s a material and historical connection from the skin to the textile, to the fabric and to the making of film. I am very interested in the fact that, at the origin of film, the editing suites were basically rooms full of women–most editors were women–sitting at these tables doing something that could have been sewing. If you look at old pictures of ‘film manufactures’ as they were called at the time, you realize they were like manufactures of clothing. The strip of film was like a ribbon–to be cut and spliced together, practically sewn.”

Surfaces and interstitial reckonings are all over Ondaatje’s affinity for maps. A map is a collage of arbitrary endpoints, as is most of human love.

B. “This is the strange life of books that you enter alone as a writer, mapping an unknown territory that arises as you travel. If you succeed in the voyage, others enter after, one at a time, also alone, but in communion with your imagination, traversing your route. Books are solitudes in which we meet.”

The Faraway Nearby

***

Anthony Strain is a writer based in Los Angeles, where he writes odd bedroom jams.

Tags: michael ondaatje