Thoughts on Masha Tupitsyn’s LACONIA, cultural criticism, the excesses of a text, minimalist critique, and living vicariously through film

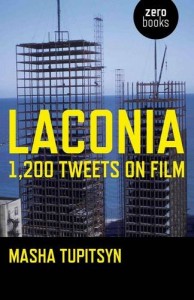

When I first read Masha Tupitsyn’s hybrid-genre book Beauty Talk and Monsters (Semiotexte), I was completely floored by it. So I was excited to read her new book LACONIA: 1,200 Tweets on Film (Zero Books)—a book of aphoristic film and media commentary written in the spirit of cultural observers like Chris Marker. There is something beautiful about Masha’s way of “reading” culture, how she honors the connections and resonances of the media she encounters, the way it is processed, assimilated and re-invented when it is filtered through her perception; intermingling with specific memories and preoccupations. Masha integrates the subjective and the critical in a way that demonstrates the specificity of our encounters with media. Both Beauty Talk and LACONIA could be described as a literary approach to film criticism, but it’s also fitting to describe the works as a cinematic approach to literary writing. In Beauty Talk, narrative and a criticism are tightly interwoven. As stories, the essays are stunning; as critical analysis, sharp. Masha’s recent book LACONIA reminds me of the ways in which the viewer is also a meaning-maker, a participant critic.

When I first read Masha Tupitsyn’s hybrid-genre book Beauty Talk and Monsters (Semiotexte), I was completely floored by it. So I was excited to read her new book LACONIA: 1,200 Tweets on Film (Zero Books)—a book of aphoristic film and media commentary written in the spirit of cultural observers like Chris Marker. There is something beautiful about Masha’s way of “reading” culture, how she honors the connections and resonances of the media she encounters, the way it is processed, assimilated and re-invented when it is filtered through her perception; intermingling with specific memories and preoccupations. Masha integrates the subjective and the critical in a way that demonstrates the specificity of our encounters with media. Both Beauty Talk and LACONIA could be described as a literary approach to film criticism, but it’s also fitting to describe the works as a cinematic approach to literary writing. In Beauty Talk, narrative and a criticism are tightly interwoven. As stories, the essays are stunning; as critical analysis, sharp. Masha’s recent book LACONIA reminds me of the ways in which the viewer is also a meaning-maker, a participant critic.

#481. IN AMERICA, WHEN YOU ATTACK THE CULTURE INDUSTRY, YOU ARE CALLED CYNICAL. BUT IT SHOULD BE THE OTHER WAY AROUND. *

“Postmodern irony means never having to say you are sorry. Or that you are serious.”

–Suzanne Moore, Looking for Trouble

Cultural studies is on the rise. The canon is dying, or at least is seriously ill. Critics are now turning their attention to the media that surrounds them—sitcoms, Hollywood films, magazines, pop music, kitsch, reality TV, fashion trends, internet memes. Repulsed by the academic elitism of cultural criticism as well as the notion that there are certain texts that are unworthy of the critic’s attention, the proponents of cultural studies have launched a vitriolic attack on the hierarchical distinction between high culture and low culture. The exclusion of “low” and popular culture and the privileging of refined culture and art that caters to a specialized/trained audience has its problems: it reinforces the idea that art is an “autonomous” institution while implicitly promoting classism, eliminating the perspective of lower class folk and ignoring subaltern cultural production and engagement (Adorno famously denounced jazz music).

So, now renegade writers and academics want to express their allegiance to the masses by talking about the stuff “normal” people like. This rebellion against the inherited values of good taste is a gesture of distain toward institutionalization, often borne out of intellectual ennui and a desire to push buttons and smash boundaries. So what you often get is hyper-intellectual readings of Lady Gaga that bring in Lacan and Butler to talk about how really-fast-cars represent the lesbian phallus. Undoubtedly, these critics are examining the media that dominates our society, but how populist is this gesture really when it’s inscribed within the same theoretical discourse? While this new cultural criticism has produced thoughtful readings of popular media, the reactionary tendency causes some critiques to lose their critical edge, generating a mindless, celebratory attitude toward media that focuses solely on, say, the queerness of so-and-so’s outfit, while ignoring the circuits of production that surround the text being considered. (How do audiences assimilate media? Who produced/distributed the film? Who were the laborers who made the dresses worn by the celebrities? Was there a target audience? In other words, how does the text exist in the world, how did it come about, what are the material realities of its production/consumption, how does it move through bodies, what bodies does it touch, what does it do?)

So, now renegade writers and academics want to express their allegiance to the masses by talking about the stuff “normal” people like. This rebellion against the inherited values of good taste is a gesture of distain toward institutionalization, often borne out of intellectual ennui and a desire to push buttons and smash boundaries. So what you often get is hyper-intellectual readings of Lady Gaga that bring in Lacan and Butler to talk about how really-fast-cars represent the lesbian phallus. Undoubtedly, these critics are examining the media that dominates our society, but how populist is this gesture really when it’s inscribed within the same theoretical discourse? While this new cultural criticism has produced thoughtful readings of popular media, the reactionary tendency causes some critiques to lose their critical edge, generating a mindless, celebratory attitude toward media that focuses solely on, say, the queerness of so-and-so’s outfit, while ignoring the circuits of production that surround the text being considered. (How do audiences assimilate media? Who produced/distributed the film? Who were the laborers who made the dresses worn by the celebrities? Was there a target audience? In other words, how does the text exist in the world, how did it come about, what are the material realities of its production/consumption, how does it move through bodies, what bodies does it touch, what does it do?)

Finding and projecting transgressive narratives onto popular culture can become a game, an intellectual exercise divorced from a more socially contextualized consideration of the text. On the flipside, Marxist-inflected cultural criticism from countries such as the UK and Germany tends to offer more politicized readings (expressing both positive and critical perspectives on popular culture). It’s no surprise that Masha’s book, given its socially-oriented approach to film criticism, is published by Zero Books, the UK publisher of some of my favorite theorists and commentators, such as Mark Fisher, author of Capitalist Realism.

#510-511. I’m certainly not interested in the apolitical and empty critiques that dominate most film criticism today.

Good cultural criticism is difficult to do. On one hand, you don’t want to sound like a dogmatic Frankfurt School elitist decrying the baseness of all things popular. But you also don’t want to lapse into a mindless valorization of capitalism-guised-as-subversion. Both types of readings use a highly “motivated” (dare I say, ideologically-driven) lens to look at culture in ways that reduce, schematize, and mold texts, allowing for the loss of nuance or the jamming of media into certain theoretical frameworks. It’s true—there are no unmotivated readings, but there are readings that are more thoughtful than others, and I strongly feel that Masha’s commentary on film accomplishes what a lot of contemporary cultural criticism fails to do— it’s accessible while still being complex, philosophical while being specific; it strikes a balance between the subjective and the social in its approach. Her perspective is totally singular and specific to her way of looking without making you feel bludgeoned by some kind of Critic Ego. By the end of the book, you actually do get a feel for the architecture of Masha’s thinking.

MICROCRITICISM AND MINIMALIST CRITIQUE

“LACONIA is in part a lament of the over-production of language, a communication overload we’re incapable of keeping up with or making sense of. Where non-stop ideas and a cacophony of “innermost” thoughts scattered all over the Web are often likely to be unread and unheard—the proverbial tree in the forest. […] I use laconic language, or micro-criticism, to restore (at least for myself) some of the concentration, economy, and attention to language we’ve lost. […]What is it that we need to say and what is it that we don’t?”

–From the introduction of LACONIA

“The notion of silence, emptiness, and reduction sketch out new prescriptions for looking, hearing, etc. […] Consider the connection between the mandate for a reduction of means and effects in art and the faculty of attention. In one of its aspects, art is a technique for focusing attention, for teaching skills of attention.”

–Susan Sontag, “The Aesthetics of Silence”

As someone who tends to lean toward the side of excess, I am intrigued by this notion of compression—of aphorism and concision, and how an aesthetic of reduction might be considered alongside the technological transformation of our historical moment. To be totally honest, I have never followed a twitter in my entire life. I sometimes peek… but mostly, I feel confused when I look at them. I know that twitter, like Tumblr and other web 2.0 platforms, lends itself to rapid “updates,” quotidian exhibitionism, fragmentation and “connectivity.” In other words, brevity, speed, and immediacy, all of which very well could be antithetical to a project of economy and concentration. Speaking of the media in an interview, filmmaker Chris Marker said, “…the noise, in the electronic sense, just gets louder and louder and ends drowning out everything.” Rapid-fire sound bites, the unending buzz of commerce and transaction. But as a Tumblr user who steps outside its intended purpose (posting long-winded commentaries rather than creating an index of media), I would also agree with Chris Marker when he says, “It’s not so much the technology that’s important as the architecture, the tree-like branching, the play.”

(Masha: “For, LACONIA is, in essence, an architecture of thinking.”)

In other words, you must make-do with the technology that is available to you, subvert its logic process if it does not suit your project. Chris Marker knew a lot about that—he made La Jetée out of still photographs when he was too broke to shoot film. Speaking of the media codes and film technology, he wrote,

I found the Medvedkin syndrome again in a Bosnian refugee camp in 1993 – a bunch of kids who had learned all the techniques of television, with newsreaders and captions, by pirating satellite TV and using equipment supplied by an NGO (nongovernmental organization). But they didn’t copy the dominant language – they just used the codes in order to establish credibility and reclaim the news for other refugees. An exemplary experience.

In LACONIA, Masha uses aspects of the twitter platform (like consolidation) while transgressing the limitations that don’t suit her project (like when she writes a comment across multiple tweets). Overall, her project is to slow things down rather than speed them up, reduce rather than accumulate. While brevity often connotes generality for many, Masha’s micro-criticism is anything but general. Nor is it facile. It’s a zoomed-in view, a way of meditating on big cultural questions through a series of frames, a gesture, a projected facial expression, a quote. If we agree with Antonio Gramsci that a society’s ideology is reflected in the culture produced within it, then film criticism is one possible point of departure for social theorizing.

THE EXCESSES OF A TEXT IS ANOTHER TEXT

“Composition channels; reading, on the contrary (the text we write in ourselves when we read), disperses, disseminates; or at least, dealing with a story (like that of sculptor Sarrasine), we see clearly that a certain constraint of our progress (of “suspense”) constantly struggles within us against the text’s explosive force, its digressive energy: with the logic of reason (which makes this story readable) mingles a logic of the symbol. This latter logic is not deductive but associative: it associates with the material text (with each of its sentences) other ideas, other images, other significations.”

“Again, ‘game’ must not be understood here as a distraction, but as a piece of work…”

–Roland Barthes, “Writing Reading”

If we are to adopt a Barthesian ethos, it could be said that the act of reading is also a form of writing, that a new text is generated between the text apprehended and the person apprehending the text. Perceiving and processing a text produces an excess of meaning, igniting associations while putting disparate ideas and lived experiences into contact with each other. While it’s common to conceptualize cultural critics as “readers” and analyzers of culture, perhaps there is reluctance to include criticism in the rubric of creation…the generation of a new work itself, which, in the words of modernist poet Laura Riding, seeks “an incentive not to response but to initiative.” In an essay about Riding and the lineage of experimental modernist criticism titled “Creating Criticism,” Lisa Samuels writes, “The model Anarchism is Not Enough [Riding’s book of essays] provides for our interdisciplinary age is partly one of generative indeterminacy, a script for further process. […] Riding wants the creative act to generate other creative acts.” In other words, to inspire. To gather up the excess of one work and create something new, a parthenogenetic offspring bursting into existence.

Every encounter is combustible, poised to explode, capable of erupting into countless other “ideas,” “images,” and “significations.” Barthes asks us, “Has it never happened, as you were reading a book, that you kept stopping as you read, not because you weren’t interested, but because you were: because of a flow of ideas, stimuli, associations?” (This has always been my dilemma: there is always too much, and I feel as if I must bracket the raw outpouring that characterizes my encounter with a work.)

Within the poststructuralist milieu we are beyond the notion that such a thing as a “clean” transmission of meaning is possible, but the danger of this is that people lapse into a kind of postmodern nihilism that emphasizes the absence of meaning. If the work under consideration is an absent referent that is only activated by the viewer (as opposed to the idea of a work doing something to the viewer), then it becomes impossible to be critical of anything because everything is essentially what we make it. But Masha’s way of reading and writing about film transcends this opposition by approaching her encounters with media as an interaction. Masha’s criticism strikes an important balance: it holds that the creator is not absolved of ethical responsibility for their work, but, at the same time, they are not the sole arbiters of meaning and there is room for the viewer to creatively interpret and integrate a work.

Put simply, this collection concerns the person, not just the work, for as Joe Baltlake writes on his blog, “The Passionate Moviegoer,” “The way a person connects the lines; the way he or she responds to a movie, says a lot about them.”

–From the introduction of LACONIA

The only criticism I find really compelling is the kind that incorporates subjectivity, the kind that is built around the idea that the reader-writer of culture is a conduit through which media is filtered. The body that the media travels through, the marvelous specificity of her entire being and the sum of her lived experiences, cannot be ignored. What is to be gained from disregarding the relationship between the artist and their art? In tweets 1024-1027, Masha writes, “…it is a privilege not to consider or, in some cases even acknowledge, the filmmaker behind the film. To suggest that representation is isn’t part of a larger system. Like Foucault, White is saying that the privilege of aestheticization, of being ‘apolitical;’ of orphaning cultural production, is just that, a privilege.”

*

The scope of LACONIA is immense—so immense that I have been struggling to write this review for several months (when there is too much to say it becomes difficult to say anything at all). I could write infinitely about the many topics that Masha brings up in her book.

For example, David Lynch, female masochism, and the unaccountable auteur:

#273-281. Suzanne Moore on David Lynch’s representation of women and sexual politics: “To complain or even to raise questions about Lynch’s treatment women means you have been caught in the Lynch mob’s favorite noose. ‘Oh, God, you didn’t take it seriously, did you? How frightfully unhip to think a scene about torturing women is really ABOUT torturing women…’ I wouldn’t ask [Lynch] for sanitized sexual politics, yet he constantly refuses to analyze what he is doing…Thus he pulls off the remarkable feat of being both the ultimate auteur and yet somehow not responsible for the content of his work. So who is responsible?…What bothers me about Lynch is that the innate death wish of the American Dream is carried out literally on the bodies of women…Like the surrealists. However, Lynch uses women to represent the unconscious itself… What once looked like a critique of sexual relations between men and women, now looks more and more like a superbly constructed reinforcement of them. Sadism and masochism may underlie all our relationships, but Lynch is not interested in asking why. Evil is not explained socially, but in morally vague terms as a presence ‘out there in the woods.’

Subjectivity under late capitalism:

#407-408. Personality is now synonymous with brand. Being alive means being for sale.

And a lot more…everything from the assholery of Noah Baumbach to the screen mythology of John Cusack to cinematic representations of gentrification to mid-flight reflections on Night at the Museum 2: Battle of the Smithsonian (which she hilariously describes as a “signifying mess. A paean to a culture of non-differentiation”).

Night at the Museum 2: Battle of the Smithsonian

THE THEATER OF MYSELF

#686-692. Whenever I rode my bike down Provincetown’s Commercial Street as a kid, I was dressed in tomboy wardrobe and makeup: short hair, plaid shirt, jean jacket, jeans, Adidas sneakers, walkman; a gender-bending, outsider ensemble I had self-consciously assembled based on the movie boys I’d seen. At a young age, I understood the power and theater of clothing. In Provincetown, where I was allowed to drift relatively unsupervised, I added music (a score) to much of what I did, building a mood around my excursions, cruising around a town full of adults, and was aware, even then, that I was enacting a dramatized (cinematic) image of aloneness. The story of girl solitude, which I thought I could only play as a boy. I screened the image of aloneness for other people’s benefit, which was my benefit. I was both in and outside the theater of myself.

Are we cinema’s shadow or is cinema our shadow? Is humanity’s image reflected back to us on the screen, or do we emulate what we see, live out our lives performing cinematically? Maybe Baudrillard would say that, within the “sacramental order” of postmodernity, the simulation is considered the originary point of reference: the film precedes the lived experience, the map precedes the territory, real geographic locations are the reflections of the Disney World miniatures. What would it mean to disrupt the sacramental order? Perhaps it would entail de-naturalizing the “sign” or the representation by not mistaking it for the real. I can remember being duped into conflating the representation with truth of a higher order, of conceptualizing of my life as some kind of faint reflection of cinematic reality— when in many ways, I was making it real.

#10-11. In The Savages the erosion of the line between onscreen and offscreen is the result of dementia. The senile father can’t tell the difference because he can’t remember the difference, making our inability to differentiate between reality and representation a form of derangement.

There are times when the truth of the image seemed to be affirmed by what I have lived. I was living in China when I thought of Bergman, of the film Scenes from a Marriage. A foreigner, I was living on the edge of extreme alienation, and I sought friendship in unlikely places, developed obsessive relationship with people I would never have even been friends with in the US. A manic depressive, vulgar Korean girl cartoonist; a macho-flamboyant Hungarian philosophy student with a penchant for argument and over-rationalization. My friendship with the Hungarian guy M. was trying; we were perpetually yo-yoing between moments of intense intimacy and outright war.

Walking around the streets of Kunming in the rain, my feet went numb. He was fucking terrible. Always trying to cut me out of his life without a reason and in the cruelest way imaginable, only later to want to come back in, to make up. But without asking. He always had too much pride to initiate reconciliation. He had too much pride to say, “I’m sorry” and I was always so quick to forgive. I forgave him, over and over. He didn’t even have to ask. I asked him: tell me you are sorry. He refused. He said that demanding an apology was fucked up because people are subjects—not objects that exist for other people—and that by asking him to apologize I was not accepting him on his terms; I was turning him into an “object” by trying to change him. Fucking philosophers. You think you can be a shithead to everyone around you and get away with it because of some convoluted ethical argument you concocted in your head? One time we argued about “the meaning of friendship.” Am I your true friend? He said the question was stupid. “It’s not about the feeling or the label. I show my care for people in my actions.” Your actions? You’re an asshole. You’re the only one I can talk to here and you’re an asshole. In your fits you were always saying, “The only thing which I think I could do is separate more from the outside world and you.”

I was meeting him at the cafe to tell him how terrible he was. I wanted to be mean to him. I wanted to yell at him and tell him to fuck off and cut him out of my life forever. But I couldn’t. When we sat down I just started laughing and said, “I’m never sad, haha!” I wanted him to give me my letter back so I could rip it up.

Johan: You need to put a lot of effort into not caring.

—Scenes from a Marriage

I wanted to be cruel to him but when I saw him I couldn’t do it. He was nervous and I was nervous, touching everything and compulsively drinking water and I asked him if he thought we should still be friends and he said yes, and in those moments of silence—moments imbued with so much tension—he would say the most morbid shit. Things like, “If you were to kill yourself how would you do it?” and a conversation about suicide or life would ensue. Him talking about leaning over the edge but being physically unable to move the body toward certain death—some biological life-force stopping him, halting his muscle functions. Maybe he wanted me to pity him. I told him that I wanted to be mean to him, but that I’m just too fucking forgiving. I can’t stay pissed. He insisted that it was a good thing, and I insisted that it was a bad thing. I asked him when it was a good thing and he said, “in situations like this one.” I imagined my relationship with M. to be living evidence of a Bergmanian truth about human relationships. The pulsions of cruelty and tenderness between Marianne and Johan in Scenes from a Marriage bore an uncanny resemblance to the dynamic between M. and I.

Marianne:

I’m not angry, but I’m on the verge of tears. The trouble with me is that I can’t get angry. I wish that for once in my life I could really lose my temper, as I sometimes feel I have every right to. I think it would change my life. But that’s not the point. You spoke earlier about loneliness. That bit about being strong on your own. I don’t believe in your gospel of isolation. I think it’s a sign of weakness.

My life, a pale reflection of a Bergman film? Or perhaps I was living out the trope of strangers drawn together by their mutual alienation, a trope found in movies like Lost in Translation (a crappy film, I might add). Unlikely connections were forged on foreign lands, emotions amplified by the temporary nature of the encounter. We would both eventually leave; would scatter and return to our “homes.” And while he was there—in China—he wasn’t actually there; he was displaced by the awareness that he would leave. Kunming is a trap, he said. Afraid, made vulnerable by attachments that would inevitably end in ruin and departure. He was always trying to get away from everyone. After returning to Hungary he would refer to Kunming as his home. After all that resistance to feeling any affection toward the city and the people living in it.

I believe, perhaps falsely, that everything I saw in the Bergman movies was true. That people were cruel and intense. One minute people are so tender and loving, the next they’re violent and hostile. In the end you don’t know if it was love, hatred, or indifference that you felt for the other person.

#425. “It seemed real. It seemed like us.” Raising Arizona

And I thought, this is how people are. This is how they relate and communicate with each other. It was only later that I could recognize that the cinematic cruelty wasn’t a universal characteristic of interpersonal dynamics—I was just hanging out with someone who acted like a jerk.

#755-763. Last night, while watching Whatever Happened to Baby Jane?, a film I find both interesting and infuriating, I thought about what the film scholar Robin Wood said about Ingmar Bergman: “Bergman has constantly and consistently confused ideology with something like the human condition. The misery in which his characters generally live is seen as something unchangeable, but there is no criticism of the culture that has produced these people. It’s as though everything is eternal—life has always been like this, life is always going to be like this. I’m always annoyed at the way in which you reach a point in several of [Bergman’s] films where the relationship between the characters seems to be going rather well, and then, suddenly, there’s a jump—everybody’s miserable again, and you hardly know what’s happened…We never know why everything [goes] wrong; it’s just assumed that everything must.” It seems, as Wood points out, that a lot of pain and confusion could be avoided or transcended by simply having characters (and people in real life) communicate vital information, not only at key moments of conflict and danger, but as a way of maintaining daily harmony and intimacy.

*

We watched Jim Jarmusch’s Stranger Than Paradise while sitting upright on my bed. I thought it would be a funny thing to watch, as it brought together both of our “homes”—Hungary and Florida. You translated the hilarious jabber of the old Hungarian woman Aunt Lotte while I told you about the tackiness of Old Time Florida, the anti-paradise, and about working in a decaying beach hotel that now serves as a hub of criminal activity. I knew that you couldn’t imagine my “real” life the way I couldn’t imagine yours, so we exchanged images with each other to try to convey what we could not with words. I would sometimes pander to your image of Florida the way I would with J., who always asked me about bikinis and tans.

You were the type of guy who liked directors like Lynch, Cronenberg, and Jodorowsky. I would sometimes cynically think to myself, TYPICAL! And, THAT’S SO MALE AVANT-GARDE OF YOU. When you bought a bootleg boxset of Tarkovsky’s films I thought, that’s an improvement….

You asked me about marshmallows. You literally said, “What are those weird things Americans are always eating in the movies? The puffy things they burn over campfires?” I bought you a bag of Chinese marshmallows and you refused to eat them. You claimed I was trying to poison you with unhealthy American junk food.

* All numbered quotes correspond to the tweet number in LACONIA and is by Masha Tupitsyn unless otherwise noted.

Tags: aphoristic critcism, capitalism, Chris Marker, cultural studies, experimental criticism, Film, Ingmar Bergman, Jean Baudrillard, LACONIA, Laura Riding, Masha Tupitsyn, memoir, resisting postmodernity, roland barthes, Stranger than Paradise, susan sontag

i think jimmy could have put you in the “academic” circle. it’s just a feeling.

Really enjoyed reading this, Jackie. Your perspective often makes me reconsider my own perspective, which I appreciate.

Zero Books is publishing some fantastic stuff. It’s quickly become one of my favorite publishers. Glad to see you shine such a bright light on one of their titles. I’m going to put Tupitsyn’s book on my to-get list. Thanks!

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=E_8dv-lM4ho

“Riding wants the creative act to generate other creative acts.” In other

words, to inspire. To gather up the excess of one work and create

something new, a parthenogenetic offspring bursting into existence.”

I love this!

& I love Riding.

& Jackie Wang.

More please!!!

rude

i was on that list and was not in the academic….sadddd hahaah

masha’s beauty talk and monsters is also a must-must-read for folk interested in experimental film criticism…more narrative than laconia, but aphoristic criticism is good too.

laura riding is my fav modernist wing-nut <333 one day i will have the courage to be as misanthropic and biting as she was.

friendlllyy

Writing things in 140-character units is an interesting intellectual and literary process, and surely aphorisms are by now a familiar literary and philosophical form. –and a critical form? why not experiment with a convention.

But in tweets 273-281, 686-692, and 755-763 – at least as they’re excerpted here – , it doesn’t look like the 140-character pieces are actually tweets, but rather, are coherent paragraphs broken into sentences–as paragraphs normally are–and merely presented as “tweets”. (Indeed, the quotations in 273-281 (which I can’t see the end of (?)) and 755-763 (where the last sentence is quite longer than 140 characters) are quoted as >140-character units.)

I understand that what can be done formally with tweeting is still wide open–why not flow over from one tweet to another . . . a week later?

–but it does seem that ignoring the constraint is hardly a way to explore it. (One aspect that’s calcified like a skeleton within the ‘aphorism’ is that it not only can stand alone, but must be able to stand alone.)

WY IZ DIS A BOOK

WY NOT JUS TWEET DA TWEETS

AN HOW CUM REAL TWETERS DON GET BOOK DEALZ

Canis zipppius

“So what you often get is hyper-intellectual readings of Lady Gaga that

bring in Lacan and Butler to talk about how really-fast-cars represent

the lesbian phallus.”

if this was Gawker I would say “+1″…if this was Jezebel I would say “yay, this!”…

thankfully HTML is neither of those. i’m Greek so i’ll just say “bravo”…

huh? i specifically mention how masha writes across multiple tweets, how she still uses an aphoristic mode while not adhering to the rigid 140-character format. there is a brief discussion abt it in the intro to the book.

yessss thanx for reminding me to read beauty talk and monsters. i needed to read a post like this today, thank you, wish there was more.

Yes, in a flurry of summary remarks obvious (“a society’s ideology is reflected in the culture within it”, pointlessly ascribed to Gramsci) or contradictory (“brevity […] which very well [hi, DFW] could be antithetical to a project of economy and concentration”), you “specifically mention” that “Masha uses aspects of the twitter platform […] while transgressing the limitations that don’t suit her project”.

Well, okay, your piece is a “slow” “accumulat[ion]” (why are these predicates set in (indirect) opposition?), where you’re not interested in advance-defending each assertion, but rather in building a sense of Tupitsyn’s book that is formally ‘like’ the book: both fragments and coherence.

–and I think, well, that’s fine, forget about myriad arguments, but what is “twitter” about the feed? the quotations on Lynch and Bergman, the reminiscence about being a kid in Provincetown: are these paragraphs actually re-engineered as “tweets”, or are they just being called “tweets”?? –and if the former case reasonably obtains, what’s the effect of “transgressing the limitations” of tweeting – other than to put old wine in old bottles labeled ‘new’?

I think you’re saying that the effect is that the “compression” and the (I think it has to be cumulative here) “slowing down” of Tupitsyn’s “tweets” cause or perform or at least disclose the interactivity self-consciously essential to all her reactions to movies.

–but that quotation of a Lynch discussion, that P-town self-characterization – both chosen by you – : to me, they’re not “aphoristic”, nor are they twitteristic. (They seem formally like a couple of Evan S. Connell books (?).)

So what do you think gives, Jackie? Why call this book “1,200 Tweets”, if that’s not what it is?

Notes from a Bottle Found on the Beach /

Points for a Compass Rose / my guess is you don’t write do you / not really / but you are annoying

good googling / my guess is that you tell people you are a reader / those are books that you can safely tell people are good books

here are some lines of what some readers call ‘poetry’ :

my guess is that you like to entertain concepts about aesthetic difference / and about the effects of an object’s form on one’s interaction with it / are these 5-7-5-syllable stanzas haiku

&

I will quote from The Adventures of Captain Underpants: An Epic Novel –

/ wank away Deaddog

wank on the beach / here lies poor dogsbody’s body

–in case you weren’t already aware, both Gawker and Jezebel are programmed in HTML….

i’m gay

i’m gay so i’ll just say “kill yourself”…

^ colostomy bag deposit ^

[the actual deadgod did not know this and isn’t quite sure what it means]

all the world looks pseudo to a lonely fist

do you think there is literature or intellection specific to the twitter format / come now guest / work that smallish thinking organ

^ small d colostomy bag / borrowed run-off ^

tinyurl.com/429zubp

http://tinyurl.com/3tnmjr8

http://tinyurl.com/3tnmjr8

[…] today, which I am now attempting to do, albeit indirectly. I particularly liked the review of it on HTML Giant. But it was in a review from The Big Other that I came across this quote from an interview with the […]