Mean

Arthur Krystal and Everyone’s Favorite Genre Fiction Fallacy

It seems perhaps in poor taste to post today with all of Sandy’s madness, but the way people talk about genre fiction and literary fiction has long been a sore subject for me. In graduate school (though not in my undergraduate program, where the faculty were both more open-minded and more emotionally mature), I struggled with instructors and students for reasons relating to this limp distinction. As a writer trying to make a career for himself, I struggled for a long time to find venues that would not reject my blended approach out of hand, and sometimes I still do.

Don’t cry for me, Argentina: I’m doing just fine, and in the long term I expect to do better. But it never feels good to see the things you love to make, and the things you often love to read, dismissed out of hand. Arthur Krystal thinks he’s being a brave truth-teller when he takes to The New Yorker to restate his opposition to including genre fiction in the category of literature, but he’s not being brave. Instead, he comes off as weirdly incapable of reflection. There have been a thousand articles like Krystal’s, and they always make the same very basic mistake: their conclusion (genre fiction’s inferiority to literary fiction) is also their premise. That is to say, they are begging the question. Click below the fold to see what I mean!Near the beginning of his piece, Silver uses self-deprecation to smuggle in the substance of his conclusion as a beginning to the argument. Watch how he does it:

Apparently, the dichotomy between genre fiction and literary fiction isn’t just old news—it’s no news, it’s finis, or so the critics on Slate’s Culture Gabfest and the folks who run other literary Web sites informed me. The science-fiction writer Ursula K. Le Guin, for instance, announced that literature “is the extant body of written art. All novels belong to it.” Is that so? A novel by definition is “written art”? You know, I wrote a novel once, and I’m pretty sure that Le Guin would change her mind if she read it.

See what Krystal does here? The choice of his own novel as an example is crucial: if he had chosen any other text, it would be self-evident that he should have to demonstrate that the novel wasn’t literature. This strategy is so nearly clever that it’s easy to think he might have known what he was doing; by giving up his own novel for dead, he makes himself appear humble and self-effacing even as he dodges the most significant problem of his argument: if we are to exclude genre fiction, then how will “literature” be defined? This allows him to say, without saying, what the definition will be: if Arthur Krystal likes a novel enough, then it’s literature. If he doesn’t, then it’s not.

Of course Krystal can’t say this in so many words, because as definitions of literature go it’s useless. Either Arthur Krystal alone gets to make these decisions (which I’m going to generously assume would not be his preference) or we all get to make these decisions for ourselves. We know that Krystal definitely won’t accept the latter argument because there would be little reason for him to write an article thumbing his nose at genre fiction if it were all relative anyway. The third obvious possibility, and the one to which Krystal most likely comes closest to believing, is that there are some people whose opinions about this distinction matter (people like Krystal, I guess) and some whose opinions do not. Again, he doesn’t explicitly espouse any of these arguments, because each is distasteful in its own way, or possibly because he hasn’t actually put sufficient thought into his position. But it really has to be something like one of these three.

Anyway, Krystal’s premise is clearly this: genre fiction is not literary fiction because literary fiction is good and genre fiction, though there’s “nothing wrong” with it, is not very good. The rest of his argument amounts to repeating this claim again, and again, and again, without ever quite coming clean that this is what he’s saying. For instance:

A good mystery or thriller isn’t set off from an accomplished literary novel by plotting, but by the writer’s sensibility, his purpose in writing, and the choices he makes to communicate that purpose. There may be a struggle to express what’s difficult to convey, and perhaps we’ll struggle a bit to understand what we’re reading.

No such difficulty informs true genre fiction; and the fact that some genre writers write better than some of their literary counterparts doesn’t automatically consecrate their books. Although a simile by Raymond Chandler and one by the legion of his imitators is the difference between a live wire and a wet noodle, Chandler’s novels are not quite literature. The assessment is Chandler’s own, tendered precisely because he was literary: “To accept a mediocre form and make something like literature out of it is in itself rather an accomplishment.” So it is.

Again, Krystal thinks that what he’s saying withstands scrutiny because he can find an example of another self-deprecating author agreeing that his output is not literature. And I should concede this much: some of Chandler’s writing, especially that which deals in one way or another with race, is pretty much garbage. But if the word “literary” is not merely a synonym for “good,” then there are countless examples of literary garbage. So the fact that some of Chandler’s work is not very good doesn’t prove it isn’t literature. It can’t. If, on the other hand, “literature” really does mean “good fiction,” then the distinction between genre and literary fiction doesn’t come into it: there is good and bad in each, perhaps more in one than the other (don’t ask me which: I haven’t read every book in existence) and we can leave it at that. Of course, if we did, then Krystal wouldn’t have any nerds to bully.

“Genre, served straight up, has its limitations,” writes Krystal, “and there’s no reason to pretend otherwise.” Okay, but what are the limitations? This is one of many opportunities to actually define our terms, to describe the differences between genre fiction and literary fiction. But surely we’re not going to hang our hat on the idea that genre fiction has limitations: again, this is equivalent to saying that genre fiction is that which Krystal doesn’t like. Either literary fiction is itself a genre (and therefore has its own limitations) or literary fiction is, again, anything really good, in which case we’re still confusing premises and conclusions.

This isn’t — or it shouldn’t be — hard to understand. But Krystal can’t stop, writing of “our” expectations of genre writing:

But one of the things we don’t expect is excellence in writing, although if you believe, as Grossman does, that the opening of Agatha Christie’s “Murder on the Orient Express” is an example of “masterly” writing, then you and I are not splashing in the same shoals of language.

I don’t expect excellence in writing from genre or literary fiction, because, again, both have plenty of terrible stuff. I expect excellence in writing, perhaps rather predictably, from excellent fiction.

Again, he begs the question:

Hybridization has been around since Shakespeare, and doesn’t really erase the line between genre and literary fiction. Nor should it.

I still don’t see where we’ve actually defined the distinction. Okay, sure, hybridization doesn’t erase the line. But what, precisely, is the line?

This next paragraph is the closest Krystal ever comes to telling us:

What I’m trying to say is that “genre” is not a bad word, although perhaps the better word for novels that taxonomically register as genre is simply “commercial.” Born to sell, these novels stick to the trite-and-true, relying on stock characters whose thoughts spool out in Lifetime platitudes. There will be exceptions, as there are in every field, but, for the most part, the standard genre or commercial novel isn’t going to break the sea frozen inside us. If this sounds condescending, so be it. Commercial novels, in general, whether they’re thrillers or romance or science fiction, employ language that is at best undistinguished and at worst characterized by a jejune mentality and a tendency to state the obvious.

This is really just another example of Krystal’s profound failure to understand his own argument, but it comes the closest to giving us a sense of how Krystal sees the distinction. He thinks that maybe the better term for “genre” novels is “commercial” novels, and then he goes on to describe what commercial novels are: they are “born to sell,” they are “trite and true,” they rely on “stock characters whose thoughts pool out in Lifetime platitudes.” Those are certainly bad qualities, and I definitely recognize them as applying to many “commercial” novels. But they’re a poor match for a great number of genre novels. Le Guin’s novels have been commercially successful in the fullness of time, but can we really say that they were “born to sell”? What about Stanislaw Lem? Some of his characters are perhaps a bit stock (though no less so than those of your average literary novel, I think) but they hardly think in “Lifetime platitudes.” There is nothing comforting or obviously commercial about Solaris, and yet you can’t credibly claim that it isn’t very much a genre book. Not even a hybrid, but pure genre.

Krystal hedges ineffectively with references to “standard genre” novels and “true genre fiction.” This is meant to imply that whatever counterexamples we can raise are irrelevant — our favorite books probably aren’t “standard” or “true” genre. And yet when it comes to literary fiction, Krystal gets to define it by the best of the pack (emphasis mine):

Which is not to say that some literary novels, as more than a few readers pointed out to me, do not contain a surfeit of decorative description, elaborate psychologizing, and gleams of self-conscious irony. To which I say: so what?

One reads Conrad and James and Joyce not simply for their way with words but for the amount of felt life in their books. Great writers hit us over the head because they present characters whose imaginary lives have real consequences (at least while we’re reading about them), and because they see the world in much the way we do: complicated by surface and subterranean feelings, by ambiguity and misapprehension, and by the misalliance of consciousness and perception.

This “so what” reads as terribly snotty to me, and the way that Krystal chooses to follow up on this rhetorical question tells you just about everything you need to know about the quality of his thinking on genre. “Sure, there are shitty literary fictions,” he concedes, “but so what? Conrad and James and Joyce are really, really good. Therefore, literary fiction wins.” If you feel like his thumb is in your eye, you’re not alone. If the best genre writers don’t prove that genre fiction can be as good as literary fiction, (that they can be “literature,” i.e., good), then why do the best literary writers work as support Krystal’s argument? Why is genre fiction represented by its worst elements while literary fiction gets to be represented by its best? Well, because Krystal began with the confidence that he was right, and then he tried to work backwards toward a reason.

If Krystal stops begging the question for even a second, he’ll fall to pieces. So naturally, he closes in the same way (again, emphasis mine):

Writers who want to understand why the heart has reasons that reason cannot know are not going to write horror tales or police procedurals. Why say otherwise? Elmore Leonard, Ross Thomas, and the wonderful George MacDonald Fraser craft stories that every discerning reader can enjoy to the hilt—but make no mistake: good commercial fiction is inferior to good literary fiction in the same way that Santa Claus is inferior to Wotan. One brings us fun or frightening gifts, the other requires—and repays—observance.

Presumably people say otherwise because they believe otherwise. Then many of these same people offer examples of beautiful genre fiction that does indeed struggle to “understand why the heart has reasons that reason cannot know.” (Is this going to be our ludicrously specific definition of “literature” then? Does Krystal also exclude from the category of literature any literary fiction with a different philosophical/aesthetic/political agenda from this one?) These examples are what one calls “evidence,” and Krystal has surely seen plenty since he started this argument. You don’t respond to evidence by repeating your claim and asking why anyone would ever say otherwise. They’re trying to tell you! The fact that you don’t know how to listen doesn’t mean you’ve won.

As I’ve written a thousand times before, we already have a name for “shitty no-good fiction.” It’s “shitty no-good fiction.” Why would we want to use the word “genre” that way? What did genre ever do to Krystal?

From the sounds of things, I guess that sometimes it was fun, and sometimes it sold well. (And of course, its readers were NNNNEEEEEEERRRRDDDDSSSS.) For trolls like Arthur Krystal, I guess that’s enough.

Tags: Arthur Krystal, genre fiction, literary fiction, shitty no-good fiction

yeah that dude can catch a dick.

The genre fiction/literary dichotomy

vonnegut, phillip k dick

david foster wallace

‘speculative fiction’

william gibson

far closer related to burroughs and postmodernisdm than George Lucas

The ‘no true Scotsman’ fallacy always seems to come up in these discussions. Kurt Vonnegut, Phillip K. Dick, William Gibson, DFW’s “Infinite Jest” and McCarthy’s “The Road” are all undoubtedly science fiction in my opinion, yet owe far more to Burroughs than to Star Wars (which itself is just an amalgam of westerns, WW2 movies, and samurai films, proof that the genre’s label focuses on its most superficial features).

You’ll not see me defending romance or mystery novels, but sci-fi doesn’t at all deserve to be lumped in with genre fiction. If we could agree on one defining characteristic of genre fiction, it would probably be a stagnant dependence on tropes and cliches, which is certainly present in fantasy and the two aforementioned genres. Sci-fi, however has been one of the most rapidly evolving and transgressive forms of literature in the last century.

Krystal’s attempted redefinition of this false dichotomy with the idea of a ‘commercial novel’ does nothing to improve the situation, because his criterion for a commercial novel as “[employing] language that is at best undistinguished” has nothing to do with a book being commercial, and once again if it appeals to his preconceived notion of what literature should be.

was ‘drafting’ thoughts during a conference call and accidentally posted this

I love reading about this question but hate the question itself — somehow that is possible.

Might the dispensation you give to sci-fi be due to the very ambiguity you describe? (i.e. If it is already clearly defined, then it has already been done.) What then makes all those writers sci-fi? Is it simply something to do with non-existent technology and ‘science’ ot the future? What is essentially about that from a creature-feature horror book?

damn I botched that all up.

ot -> or

What is essentially [different] about…

of course, there is another side to this coin: a lot of genre writers and fans hate any genre fiction that falls into the literary/experimental side of things. Show a David Eddings fan some messed up surreal thing and say, “hey that’s genre too!” and they’ll turn their nose up at you and say it’s not real genre. They also refuse to read literary novels (unless it has a bit of genre sprinkled in it…and even then…well, maybe not). Both sides of this have assholes and both sides claim to be shut out in the dark by said assholes. Whatever.

Been thinking about genre lately from ‘the other side’

This article has a really red state/blue state vibe to it, like snobby literati vs good ole-fashioned storytellers:

http://www.theatlantic.com/magazine/archive/2001/07/a-readers-manifesto/302270/

also saw this the other day

http://www.themillions.com/2012/10/literary-fiction-is-a-genre-a-list.html

But I kind of <3 this comment the way it is!

Yeah there’s a lot of d-bags. But, Brian Evenson has said that in his experience, most genre fans (or at least, most who are writers or very invested in reading) will also read good literary fiction if you suggest it to them. Whereas a lot of literary dudes just won’t do it.

Thanks for writing this, Mike! I agree with you; Krystal’s just flat out wrong. I wonder where this attitude comes from? It makes no sense to me. Like I wrote in this post, I’m so happy film studies doesn’t operate under this assumption:

“Just think about it: A Trip to the Moon, The Great Train Robbery, The Birth of a Nation, Nosferatu, Metropolis, Love Me Tonight, Trouble in Paradise, Duck Soup, Bringing Up Baby, The Maltese Falcon, Cat People, Heaven Can Wait, The Seventh Victim, Out of the Past, The Third Man, Sunset Blvd., The Asphalt Jungle, Johnny Guitar, Kiss Me Deadly, The Night of the Hunter, The Searchers, Written on the Wind, Touch of Evil, Vertigo, Sweet Smell of Success, North by Northwest, Rio Bravo, Some Like It Hot, Breathless, Yojimbo, La jetée, Charade, Point Blank, 2001, Rosemary’s Baby, McCabe & Mrs. Miller, Two-Lane Blacktop, Solyaris, Don’t Look Now, The Godfather Part II, Night Moves, The Man Who Fell to Earth, The Empire Strikes Back, The Shining, Blade Runner, Blue Velvet, Goodfellas, Dead Man, Babe: Pig in the City, The Thin Red Line, The Limey… all widely regarded as great works of art, and all indisputably genre films. I mean, no one in cinema ever says anything as laughable as, ‘2001, great movie—but of course it’s not really science-fiction…’”

I don’t trust anyone who doesn’t read widely.

My fiction workshop told me that the Millions article was a joke, but I read it seriously. Seemed right to me.

I’m not sure why Krystal dismisses “bad literary fiction” with a “so what?” Now there’s a topic ripe for further exploration. The “literary” genre is flooded with plodding, safe, commercially-appealing work that lacks any style or originality whatsoever, which was sort of the point behind William Giraldi’s takedown of Alix Ohlin’s style. The fact that the self-righteous, morally outraged-at-everything pitchfork crowd missed the point and even downplayed his attention to language speaks volumes. I don’t care if a novel is sci-fi or literary as long the writer has a unique and original voice, yet the predominant voice in mainstream literary fiction is Weatherman’s Voice

Mike, have you (or anyone else here) seen Cloud Atlas yet? Jeremy was visiting last Sunday and we wanted to go, but couldn’t quite find the time.

I haven’t. Was going to go Sunday but the friend I wanted to go with didn’t have time. Wish we could see it together! I assume I will like it much less than the book (I don’t like the idea of a focus on all the souls moving through time, and I really don’t think Tom Hanks makes sense in some of those roles, or that Halle Berry is ever good in anything) but I want to love it anyway.

I want to love it, too. I’m actually a pretty big fan of the Wachowskis. I adore the Matrix films (irrational of me, I know). I love the idea of them adapting Cloud Atlas—and with Tykwer! It seems to me the biggest cinematic gift of the year. Even if it’s no good, I feel I have to admire the attempt…

Depends, Brian Evenson’s genre base leans more towards the literary side of genre anyway. That’s like saying I know some literary people that really read widely and like genre fiction- it’s not a truth it’s an anecdote. There are a lot of people who cross the bridge on both sides, but there are even more people who yell and hate at each other. One side: it’s not literature. The other side: there all elitist bastards who think they’re smarter than us and their books are just confusing on purpose to make us stupid.

Not that there aren’t awesome people on both sides of the fence, either. I just kind of think it’s strange that we hear all the time about genre being ghettoized, and yet the same kind of arguing happens on the other side too.

Weatherman?

I liked the first Matrix movie okay, and I am very much on their side for the sheer ambition. But they made the V for Vendetta adaptation, which should have been pretty easy, such a limp, silly political argument about liberalism vs. conservatism when the original graphic novel was so much more interesting, and that makes me nervous.

That’s pretty much what I was trying to say above. Sometimes I call genre fans the tea party of fiction for a reason…

They didn’t direct V, though.

I adore the Matrix sequels. I know, I know. I’m delusional.

But I’m bonkers for them.

I read it seriously. The precious/cutesy long title entry is dead-on: a preposition (like “when” or “if”) + second-person or first-person plural + and some pseudo profound declarative that tells me how I’m supposed to read your twee book before I open it. Right away, you’ve lost my trust as a reader. Give me a simple, subtle title that’s about the book, not you.

The difference is that literary writers use the university and other positions with cultural power (i.e., The New Yorker) to pick on genre writers. Genre writers can’t really do that or anything like it. The worst most of them can do is write angry stuff on blogs and not buy books they don’t want. Literary writers complain that genre writers get all the money, but a) that’s not their fault, b) most of them don’t, actually, and c) of course they do.

I could pick on you over this, but it would be too easy.

Awesome point, and I think it really highlights just how silly the genre-snobbishness is in the lit world. I wonder when the war on genre started?

I’ll take it if you do. I was thinking earlier that it was finally time for me to write my post on why I love Keanu Reeves…

I have a huge crush on the Matrix sequels. Right there with you.

I have absolutely no idea. I’d guess it was in the 1970s, though, when everyone and their mother started attending/graduating from MFA programs, and major press funding for less commercial lit started drying up…

I responded to them by going to Kenyon Review Online and picking the very first piece of fiction I could find.

Which turns out to have a barking dog (well, the waves lapping the side of the boat— scenic description of a sound used to “show” the passing of time”), and follow the “scene, exposition, scene, flashback, scene, cue epiphany” pattern exactly.

I really love romance novels. I tried to write a “good” one for a long time. It was pretty fun. I think romance gets dumped on so unfairly.

Excellent! There are two of us, then! I watch them once a year! Join me next go-round!

See my very next post! I’m a huge fan of romance, too, and am currently trying to write a good one myself…

Meh. That’s about all I got right now. Meh. I’m sick of the fighting on both sides. It’s annoying.

Wha? You trust a writer? Pfah. Never trust writers. They lie for a living. (also side note: I like long titles. I also like one word titles. And three word titles. And titles that are just letters. And titles that are the same word repeated over and over again.)

All of my favorite “realists” borrow from genre (Dickens, FOC, Joy Williams,etc.). Poe, a genre writer, basically invented the modern literary short story. In my PhD program, I studied the fin de siecle Victorian writers–like Conrad and Stevenson–and studied how they borrowed, cut, and spliced multiple genres (horror, thriller, detective) and modes, how they played with form. It was liberating. I’ve learned more from British and American classics like Jekyll and Hyde, Country of Pointed Firs and Winesburg, Ohio than most contemporary books.

So yeah, I’ll never understand why some writers eschew wildness, or, as Barthelme famously said, “wacky mode.” Much of what’s labeled “realism” today is nothing like the loopy realism of Dickens and FOC, which angers me most, because history has shown that the best realism isn’t “realistic.” Historically, the best realism has been free and open, not a parody of itself.

Of course I trust a writer who is asking me to devote several hours reading his or her book. Would I trust a writer outside of writing? To work on car? Operate on my brain? Take my daughter to the prom and return her home safely? Well, those different questions entirely and have nothing to do with the kind of artistic trust a writer is obligated to establish on the page with her reader.

I don’t dislike all long titles, either. I dislike long, insincere, cutesy titles of the Eggers/McSweeney’s/Twee variety. We all know those titles when we see them.

I haven’t enjoyed a fictional romance in a long time. But I want to! And the idea that it’s an inferior genre is pretty clearly one with sexist, rather than logical, roots.

The mistake is to think that literary quality resides solely on the (self-proclaimed) literary fiction side.

Barry N. Malzberg is as good a writer as anybody. So is Patricia Highsmith. So is Jim Thompson. So is Agatha Christie. If people can’t recognize that fact, if they think that the only good writers are the ones who are taught in MFA programs and published in Best American, then fooey on them!

They can pry my Frank Miller comics from my cold, dead fingers.

J. Y. Hopkins, I love your gravatar; it looks like a happy cat’s face.

Agreed. See my post tomorrow morning? Will be curious to hear your thoughts…

abysmal, despite my quibble over the romance and mystery genres, I generally agree with you…

Harry Mathews’s great novel Cigarettes (1987) is both a great romance novel and a great mystery novel.

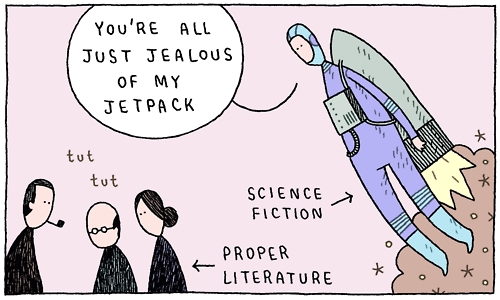

Incidentally, the image you put at the top of this, I first saw it at the used bookstore Uncharted here in Logan Square, taped to the sci-fi section’s bookshelf.

I think that most genre hacks are offended because they confuse the term “literary fiction” with literature. Literary fiction is a genre of its own, and it isn’t necessarily literature. Much of it is written, like genre fiction, to please a certain market segment. I would contend that no one who writes to please a defined market can be taken seriously as an artist, and his product, literary or not cannot be considered literature. To be literature it must be uncompromising, untainted by commercial considerations and the expectations of a defined category of readers. It must transcend those categories, not pander to them, as all genre fiction does. That is why good literature is usually found among the outliers, not among the mainstream lists “literary” or otherwise. I would venture that is the main reason why classics go unrecognized in their own time.

Film makers and film buffs seem to have a better appreciation of how things “work”and how to create effects that seems not to exist in the writing world (careful non-use of literary ie lit world). Perhaps it is because there is a stronger acceptance of using techniques/tricks within film, perhaps there is a greater acceptance that film is primarily to entertain whereas ‘lit’ is supposed to inform and be profound in some way. But then there are excellent filmmakers who use techniques/tricks splendidly and creatively, compare that with pap filmmakers who use them dishonestly, eg the preponderance of fake handheld cam shakiness, or frequent jump cutting a la Nolan. Perhaps that is the similar difference between high lit and pulp novels. Note that pulp wouldn’t work with the stories peddled as mainstream literature–they just aren’t entertaining enough.

In both arts 99% of all of it is crap, let’s be brutally honest. I read and watch movies as an appreciater as well as to be entertained, so there will always be those of us who want high art. But the more shallow will entertain, it will sell. Can’t fight it.

Said all that, I proudly peddle fantasy novels. At least, that’s how they’re dressed.

I don’t think he’s really wrong. He’s mistaken his opinion for a fact. Generally, genre fiction is more focused on plot while literary fiction is more focused on style. Whether a reader prefers one over the other depends on their taste.

I’ve always wondered why genre films are thought of so differently than genre books: more respected/mainstream. Speculative fiction authors and readers refer to literary fiction as “mainstream.” I thought that was really odd when I was working for a genre magazine and hearing it occasionally considering most genre fictions seems just as mainstream to me as literary fiction.

That may be true, although I think it’s easy to see where Krystal thinks the real quality lies.

I will never understand the plot against plot. Plot is just a literary element. It is neither good nor bad. It is a tool. Focusing on plot does not make a work a piece of genre writing, or bad. Nor does it make it good. Plenty of classic works of literary fiction whose value is not in doubt are heavily plotted: Gilgamesh, Beowulf, Sir Gawain and Green Knight, Paradise Lost, Hamlet, Don Quixote. The Portrait of a Lady, The Sheltering Sky, The Recognitions, Gravity’s Rainbow, Watchmen, Cigarettes. I could name countless others.

What’s more, there is so much that can be done with plot. Consider Rudy Wurlitzer’s beautifully strange novel Nog. A great deal happens in that novel. (I recently rewrote the Wikipedia plot synopsis for it.) And the novel’s effect depends on a great deal happening. At the same time, the novel’s presentation makes it very difficult to tell precisely what is going on at any given time. That’s how it comes across as psychedelic. If nothing much happened, it wouldn’t have anywhere near the same effect.

Of course, a book having a plot is no guarantor of anything. It really all comes down to what the work’s ambitions are, and how the plot is used.

Don’t get me wrong. I love plenty of plotless works that focus instead on rich portrayals of character psychologies. I love Carver, Beattie, Cheever, Yates. I love static works where very little happens—Marguerite Duras and Alain Robbe-Grillet are two of my all-time favorite writers. I also love writers like Donald Barthelme, who privilege language over plot, over even character psychology. Fiction is richer for having all those magnificent writers. But at the same time I also love Carl Barks‘s Uncle Scrooge comics. How could I not? They are brilliant works of literature.

Fiction is vast, bigger than all of our tastes combined. There is so much to love. What I hate more than anything is when someone with very narrow tastes comes in and declares some corner of the literary landscape superior to the rest of the field. How ignorant and insecure of them.

Agreed, but genre fiction authors still generally focus more on plot than style. I think most readers would agree with me when I say the best writing focuses equally on both plot and style.

I don’t think I’ve read Carl Barks, but The Life and Times of Scrooge McDuck was pretty great.

Is that really true, though? I don’t know. I have to wonder. It may be, but I don’t think I’ve been convinced yet.

I think the problem is that when people make that argument, they’re speaking so very generally. What does “most genre writers” mean? What is the scope of the field? Can a claim like that even be true? How does one measure a focus on plot as opposed to other literary elements?

Here’s a little of what I mean. It is very common to hear someone say, “genre fiction is all about plot.” (Or mainstream Hollywood blockbusters.) But at the same time, it is also very common to hear someone say, “The plot is ridiculous, and doesn’t really matter.” (And, again, the same is true of mainstream Hollywood blockbusters.) How can both of these claims be true? I think there’s more than a little cognitive dissonance going on here.

I’ve read all of Dan Brown’s novels, and it’s true that plot is a focus in them, in that part of the reason for reading them is to find out what happens next. But at the same time, the plot is so ridiculous throughout—almost farcically so. It’s an interesting question to ask, what’s the most important thing in those books? Is it the invented historical details? The puzzles? The suspense? I think those three elements, while held together by the plot, surpass the plot in terms of importance. A plot synopsis of Angels & Demons is actually quite boring.

(Do people really read comics for their plots? I’ve read the first 300 issues of Uncanny X-Men, and found the overall lack of plot to be the worst part of it—it’s almost unbearable how it never goes anywhere, except for a few issues at a time. But then everything resets, over and over again. Characters die and come back to life. Different couples form. Prof. X loses the use of his legs, then can walk again, then loses the use of his legs again. It’s not really what you’d call “plot.” It’s just stuff happening. Meanwhile, by way of comparison, Dave Sim’s 300-issue comic Cerebus is extremely heavily plotted. But it’s not what you’d call a genre work. It’s massively strange and experimental and challenging—a real investigation into how time and narrative work in comics. I don’t think it’s unrealistic to compare it to Proust. And a lot of comics are like this—usually it’s the “more serious” indy ones that are invested in plot, whereas the superhero ones really treat plot as something disposable.

All of this is to say that I think the issue is far more complicated than it’s commonly presented as being. I really have been spending a great deal of time—too much time, probably—thinking about this.

Because I am extremely interested in where this perception comes from. Why do so may critics and readers consider plot a bad thing? I wrote about that somewhat in this essay (on Harry Mathews’s extraordinarily carefully plotted experimental mystery/romance novel Cigarettes), and plan to write more about it, no doubt write far too much about it…

Cheers,

Adam

Yeah, it’s true. When I say “most genre writers,” I mean I have read more genre writers that don’t focus on style than genre writers who do. A typical speculative fiction book has prose that competently written, but not great. A lot of the books read as if they were written by the same author. I guess people have the same complaint about literary fiction books as well as far as the “MFA style,” but I don’t really notice it, except for years ago when I read a lot of literary journals.

The Da Vinci Code is a pretty terrible book. I think what kept people from “putting it down” was the suspense and all the interesting (although false) ideas Dan Brown ripped off from Holy Blood, Holy Grail.

I don’t know why people read superhero comics. I think I read them for the same reason people watch soap operas. I love serial narratives. It’s pretty amazing that I’m reading about the same characters who I followed in elementary school. That appeals to me. Seems like comics were for kids back then and more for adults these days. Unlike now, there were no superhero comics that were written exclusively for children. I sort of feel like the comics and I grew up together.

I’ve never really noticed critics and authors considering plot a bad thing. Instead, they consider genre fiction plots a bad thing. Perhaps because there’s more of a sense of escapism, and maybe they think escapist entertainment is juvenile. It’s really easy for them to notice the tropes of genre fiction and ignore that literary fiction has tropes as well.

I’m thinking another difference between genre fiction (with the exception of romance) and literary fiction may be that genre tends to focus on external conflict while literary often focuses on internal conflict. And once again, the best fiction focuses on them both equally.

Really, nearly every work of fiction has a plot, although some authors focused less on it while writing.

[…] on Mike’s earlier post, I have long found it curious that the romance novel is the one genre no one wants to defend. (See, […]

But I like those long titles, enough to not call them twee and wonder why you have to be so condescending towards something. I mean, you don’t like it, cool that’s fine.

And I never trust a writer when reading their book. Why should I trust them? I mean, some of the best books out there have unreliable narrators (Pale Fire, etc) and that’s what makes them so great, because you can’t trust the narrator and you can’t trust the writer.

Writers manipulate emotions, right there, that should say, don’t trust any damned thing they’re about to say on the page.

Yeah, it’s not “genre hacks” who confuse the terms. Instead, that’s the basis of Krystal’s bullying, and that of others as well — the convenience of confusing literary fiction with literature.

Also disagree with, like, everything else you write here. It’s not a choice of being “uncompromising” and “pandering” to readers. “Pandering” (i.e., thinking about what your readers might want) is the only path to any kind of greatness most of us have; usually, ignoring your readers only makes tripe, and when we pretend otherwise, it doesn’t make us better writers, it makes us lazy children.

On the genre side you have the exact same issues though, exactly the same. They have their own MFA- style program (Clarion- it’s been around since the 60’s) that pretty much gives the writers they go there a leg up on everything, and you hear all the time how great it is and how it gets people out there, etc.

I mean, how is that any different? How is “the best writing” being in the Years Best Fantasy and Horror any different than the best writing being in the Best American Short Stories? How is any side any worse or better about this thing?

Of course, since the genre writers think they’re just gosh writing for the common blue collar man and telling ripping yarns and cracking stories and (insert cheesy adjective here found in a million Amazon reviews) they wouldn’t call it literary quality, but they look down on literary quality.

Both sides are wrong.

” I thought that was really odd when I was working for a genre magazine and hearing it occasionally considering most genre fictions seems just as mainstream to me as literary fiction.”

That’s because they want to see themselves as the underdog.

I’ve read copious amounts of amateur fiction of every genre on Authonomy and elsewhere. And plenty of “literary fiction” openers that went back on the bookstore shelves for being cliche. It’s rare that a book will grab me and hold my attention. That is why I think of published fiction as being on the slush pile of literary history. But to equate formulaic fiction, or fiction that is all about the gadgetry, as in the cartoon above, with work that is truly inspired may do wonders for one’s self esteem, but as a writer, I care more about producing something artful than jonesing my self-esteem.

I think you’re being needlessly over-genreal (“the genre writers think they’re writing for the common blue collar man”?), but if those genre writers think that they’re the best, and writing the only books worth reading, then I think they’re wrong, and they all deserve spankings.

It’s definitely possible to find differences between, say, Dan Brown and Tao Lin. We could make a whole list of them. So I don’t disagree with that. The question, though, becomes how to describe that. Richard Yates is all about physical conflict, for instance—Haley Joel Osment and Dakota Fanning are constantly struggling with others and their situation and, while they may not always recognize it, one another. (They’re an updated version of Frank and April Wheeler,) In Shoplifting, meanwhile, the struggles are arguably more internal, though there is that fistfight in the jail cell :)

What I always keep coming back to, though, is why one side gets privileged over the other, and why one literary element keeps getting thought of as better. Like, I know a lot of people who think literary depictions of internal struggles, psychological struggles, are more valid or artistic than literary depictions of physical or external struggles. Or that ornate prose is superior to plain prose. Or a lack of plot, stasis, superior to lots of plot. (At the same time, they’ll often then privilege character arcs and epiphanies over flat, static characters—go figure. Like I said, there’s a lot of cognitive dissonance on these issues.) (And I’m not accusing you of any of this!)

I myself don’t agree with those binaries, but I know a great many people who endorse them. I hear them all the time, in workshop and in conversations at readings.

“Prose” seems to me the biggest one. Time and again people tell me things like, “I couldn’t read Harry Potter because the prose is so awful.” They’re upset that it doesn’t read like, I dunno, Cormac McCarthy, or Sam Lipsyte. But it shouldn’t read that way. J.K. Rowling’s prose is perfectly fine; it gets cliched/repetitive at times, and it’s rarely beautiful, but it has its own charm (it certainly is distinct in its own ways—I can recognize her “voice” right away), and it serves those novels pretty well. Could it have been “better”? Sure, but it still would have been plain. Ornate loop-dee-loops would not help The Half-Blood Prince. And meanwhile, there are other elements in all the Harry Potter novels that are very skillfully rendered (especially from the third installment on). Rowling’s a master of complex, almost Byzantine plotting, and she’s great at creating indelible characters of type, and good at pacing and suspense. And she found a way to refresh fantasy, to yank it away from an endless sea of Tolkien imitations. Those are all very real and very literary accomplishments, in my mind, and Rowling is worth reading because of them.

No one element in fiction is more important than any other, and it shouldn’t have a litmus test.

Yes, but aren’t all the conversations we’re having on this general? I mean we’re just lumping into two camps, right?

I guess in a way we’re just talking about the circular arguments that get repeated a lot that have become straw men dressed up as memes.

Spankings all around!

Well, there’s general, and then there’s over-general!

I’ve been trying to push toward some actual texts.

I don’t know if all genre fiction can really be lumped together so readily. There’s a world of difference between J.R.R. Tolkien and J..K. Rowling. And a world of difference between them and Barry N. Malzberg, and Philip K. Dick. And Jim Thompson and Patricia Highsmith and Agatha Christie. And a dying earth’s world of difference between all of them and Jack Vance. To name my very favorite “genre” writers.

I think the problem, whenever this issue comes up, is that people tend to focus on a lot of bad writing. They pick the worst aspects of a genre, and extrapolate that all of it is like that. There is, to be sure, a lot of bad fantasy writing. But Jack Vance and Tolkien and Rowling are not bad writers, and their work is interesting and innovative in a variety of ways.

… But you’re speaking to someone who’s getting a PhD in English, but who grew up reading X-Men comics and Hardy Boys novels. And who graduated to Michael Crichton and Star Trek novels and Tom Clancy.

I, too, deserve spankings.

LOL, guess you responded while I was editting my post above. Either way, we’re both picking at popular versions of both fictional forms.

If you *do* like genre fiction than you need to explore the crevices to find some outstanding writers that are great prose stylists and combine a literary aesthetic to a strange hybrid genre mold. Like, for example, Jeff Vandermeer. Or Lavie Tidhar’s Osama. Or Ekaterina Sedia’s books. Or Kelly Link. Or…well, I could go on and on.

I mean, I can understand you wanting to defend the genre you like, and that’s cool and okay and everything, but there is a lot of writers out there trying to take genre to the Nth level, and to see them ignored by both sides of this debate makes me wonder what the debate is even about. Other than the pro genre people wanting to like their comfort food and lit people liking their comfort food and both ignoring the crazy, extreme experimental stuff in the fringes of both.

I know Jeff VanderMeer’s work, and Kelly Link’s. I once had the privilege of publishing an excellent short short by Jeff (“The Mimic”) in a small zine I once helped put out. And I’ve also had the privilege of seeing one of my own stories, “The Wolves of St. Etienne,” being published by Kelly, in her Lady Churchill’s Rosebud Wristlet.

Lavie Tidhar and Ekaterina Sedia I’ve been meaning to check out for a while now; many of my friends have especially recommended Sedia’s work to me. I shall redouble my efforts!

I will say, though, that I don’t think one has to go to the fringe or the Nth level to do strange things. I used to think that myself—I spent a long while being interested only in the most bizarre writing and art out there—but I eventually realized that innovation is everywhere, and a lot of very strange stuff passes for “normal.”

I’m interested in work being done everywhere, above-ground and underground, popular and fringe, genre and “literary.” Indeed, I think it makes more sense to look at traditions and lines of influence than at genres. For instance, “O’Henry was a huge influence on Donald Barthelme.” Or, “Kurt Vonnegut was very influenced by Céline.” (It’s crossovers like these that put another lie to the mainstream genre/underground lit divisions. As I always point out, Barthelme wrote a piece of Batman fanfiction—and a really excellent piece, at that!)

The only reason I brought up those writers because I felt like, somehow, they get sidelined when people discuss this sort of thing- and both sides seem to dwell on *NAMES* like Tolkien and Rowling and etc.

What zine did you take part in?

LCRW is good stuff. I used to have a subscription to it for awhile. But I think I mispoke above, because really I don’t think Link and Vandermeer et al are in the fringe, you know. I just meant, it seems like everyone mentions big namey names and ignores all these other current contemporary writers doing interesting things that are different things. I didn’t just mean it can only be done outside of this and all that, but it seems odd that when people bring up and defend genre fiction to a literary audience they always defend names that have mediocre at best writing, dwell on plot, and are in the end basically comfort fiction of sorts.

Now I’m rambling. Anyway, I didn’t mean to take shots at what you like or whatever, I’m just saying some of the stuff out there is all about being hybrid and they’re doing really interesting things and not being normal or anything like that at all. I’m starting to feel like some writer somewhere who said he’d rather shoot himself in the face than talk about genre anymore. Mostly because this argument is all the same argument on both sides, and it never changes, so why do keep feeling the need to repeat it?

Argh. Again, rambling.

You seem to be in desperate search of an argument. Okay, I’ll oblige you:

*Good for you that you like “those long titles,” but it’s not “condescending” to call many of them “twee.” Miranda July and Dave Eggers are largely responsible for the popularity of those titles, and I’m not the first person to suggest that both writers are twee and in fact embrace tweedom.

*Once again you misunderstand my use of “trust.” Your unreliable narrator example doesn’t work because an unreliable narrator is separate from its author. An unreliable narrator’s effectiveness also depends on how convincingly it’s drawn, and artistic effectiveness (or the willingness to suspend disbelief) depends on an assumed trust between reader and writer. You conflate narrator with author. Why? And yes, of course writers manipulate rhetoric in order to charm readers through fictional devices–your point? That’s not breaking a reader’s “trust.” That’s called, “fiction writing.”

I think it’s “funny” that you have to “resort” to “air quotes” in order to “express yourself” online. If, however you “meant” to use these “quotes” as ways of signifying “importance” there is always the “italics” or “bold” to make a correct point without “implied” “sarcasm” strewn “throughout” your “text”.

I think it’s “funny” that you can’t even get the common criticism of air quotes right, which is that they are usually “unnecessary” and my points would be just as “clear” without them. See edited post.

So…someone writes a stupid article filled with assumptions and lazy generalizations, a writer for this site critiques the article, everyone basically agrees with the second writer–people on “both sides”–and yet people are taking sides. Troll much?

Yes. YEEEES

Or that they’re annoying, which is kinda my point. Air quotes are implied sarcasm…so removing them does change your meaning and makes it less clear, if you were using them for that purpose. If, on the other hand, you were using them to emphasize your point then you were doing it wrong.

Here’s the evil one.

Air quotes do not always imply sarcasm online, especially when one isn’t familiar with Disqus’s boldface and italics function. My points are as clear as they were with the air quotes, Mr. Intentionally Obtuse. Keep trolling.

High-lit stuff is still paid for. And a market is just an audience. I see no reason why commercial/market considerations should chafe against the goal of making art. People buy art. People are audiences.

The market demographic for a Great Book could be something as simple as “people who like innovative writing.” “People who want writing to change the way they think about things.” “People who read discriminately ” “People who are made horny by words.” “People who want books that defy their expectations of books.”

There are so many people in the world that if you are writing a book that you yourself genuinely like to read, in all likelihood you are writing for a decent-sized audience. Because there are just too many people out there for your tastes to be quite that esoteric.

Do classics really go unrecognized in their own time? There are exceptions, but I feel like most of them sell moderately well.

You know, a novel about marketing would be pretty cool. Are there any awesome novels about marketing?

sure, or you could, you know use something less confusing like *this* which can’t be confused as “sarcastic scare quotes” in text.

Are you still nitpicking my scare quotes [that I edited several hours ago] because you have not substantial to say or add?

Um. I guess not. Why? You want to fight or something? Fisticuffs I say! At dawn!

Shit. Why can’t I stop posting and just leave you the hell alone…

I think Krystal’s use of the term “genre”–from his examples (Christie, Chandler, Leonard, etc)– indicates a novel based on reproduction of a previous novel for the sake of cloning an effect. This accounts for minute variations in the otherwise formulaic constructions of romance and mystery novels. I doubt he would classify Le Guin or Lem as strictly “genre” writers, as both are generally regarded as being “literary” in the sense that they turn the genres in which they write toward the conceptual (you don’t get this in “Ten Little Indians”, which is genre “served straight up”); Solaris, for instance, both charts a limit of its characters’ ability to study something extraterrestrial and shows how people just leave signs of themselves where they go (in other words, science really tells a human story, because humans are the ones conducting and writing it). Writers like Leonard and Hammett don’t take chances like these hybridizing authors do: they tell stories made of stock characters, phrases, and situations, in which good and evil are drawn clearly as reflections of a usually dominant political point of view, with just enough variation on form to introduce some tension into the text. I assume that Krystal does not point this out because he expects his reader to know what he means by “genre”; the Chandler quotation late in the piece serves as his support for asserting that Highsmith and others have elevated genre to literature.

It still comes down to using the word genre to mean “shitty and formulaic” when we already have words for “shitty and formulaic,” and, in the process, whether he means to or not — and I’m confident that he does — tarring a lot of good and great authors who self-identify as genre writers (such as myself).

I disagree. I think he uses the term fairly and in a manner consistent with the way it has been used for quite some time, academically, commercially, and generally; it’s difficult to escape the fact that the word “genre” derives its meaning largely from the tension it shares with the word “literature”, in that it indicates a kind of literature heavily invested in emphatically formulaic techniques (such as the explication of the crime in a mystery). Nor do I think Krystal sets the bar that high for what it takes for genre to make Team Literary, given the list he sets out. Perhaps you disagree. But that is fine. It doesn’t make much of a difference to argue about this–as Krystal’s relatively relaxed tone suggests (check out his other essays to see him in a more assertive mode)–because good books stand out, genre fictions or not.

Response from a genre writer…worth a read:

http://rsbakker.wordpress.com/2012/11/03/the-anxiety-of-irrelevance-an-open-letter-to-arthur-krystal/

Yes, somebody else knows Barry Malzberg!!! such a good writer

[…] “Arthur Krystal and Everyone’s Favorite Genre Fiction Fallacy“ by Mike Meginnis (from HTML Giant) Mike bends and blurs genre; such as his recent “Navigators” originally published in Hobart and then included in the Best American Short Stories 2013. He also defends and defines genre as way to compel plot, while also still being a good story. Have a read and then weight in on the conversation in the comments section. […]

[…] “Arthur Krystal and Everyone’s Favorite Genre Fiction Fallacy“ by Mike Meginnis (from HTML Giant) Mike bends and blurs genre; such as his recent “Navigators” originally published in Hobart and then included in the Best American Short Stories 2013. He also defends and defines genre as way to compel plot, while also still being a good story. Have a read and then weigh in on the conversation in the comments section. […]

[…] genre author Lev Grossman, followed by Krystal publishing a rebuttal to that. A plethora of other blog posts, articles, and essays stemmed from this […]