|

The Cantos of Ezra Pound

by Ezra Pound

New Directions, 1996

896 pages / $25.95 buy from Amazon

|

1. In the Middle Ages, as a practice of divination, as a method of drawing lots and to soothsay, to learn what might be the wrath to come, to draw out a linear progression from a dark mass of chaos, those with access to Virgil’s Aeneid might practice Sortes Vergilianae. The instructions were simple: fetch a copy of the epic poem, let the weary spine fall where it may, and whatever passage the eye lighted on the reader interpreted as indicative of prophecy.

2. My copy of The Cantos of Ezra Pound is a fresh New Directions paperback with the spine still intact. Regardless, it looks ominous. The backdrop black with serifed white letters stamped down on the cover. At twelve years old and knowing nothing of Ezra Pound, I picked the book up because it looked Biblical and heavy, like תֹהוּ וָבֹהוּ, the waters of Genesis 1:2.

3. The Cantos present chaos before the Spirit of God levitates over the deep. Although Pound principally brings forward “light” as his favorite element of spirituality and mysticism, darkness pervades the poem. It’s universally acknowledged that the work turns on an axis based more on Inferno than Paradiso.

4. Interviewed by Donald Hall in The Paris Review, who spent three days with Pound in Italy during the early 1960s, a restless and writer’s block-inflicted Pound comments, “It is difficult to write a paradiso when all the superficial indications are that you ought to write an apocalypse. It is obviously much easier to find inhabitants for an inferno.”

5. After publishing Thrones de los Cantares, the penultimate section of the Cantos, Pound admits, “Okay, I am stuck.” One imagines him gazing out the window, sunlight revealing a Roman street where, if you dig far enough, discoveries of pagan rites abound. He continues, pulling at his beard, “The question is, am I dead.”

6. The aforementioned Hebrew typically translates as “without form and void” (KJV). It can also mean “utter confusion,” a feeling most readers share when tackling the Cantos. Pound’s classic outline for his epic poem, from a letter to his father (who was appropriately, I kid you not, named Homer), begins, “Live man goes down into world of Dead.”

7. Pound, like his hero Odysseus, descended into Hell and still lived to see daylight. Kept outdoors for many weeks near Pisa, Pound was a caged panther, captive of the US military in 1943. During this time or immediately afterwards, he promptly went insane, dubbed mentally unfit to stand trial, housed in the “bughouse” of St. Elizabeths Hospital for thirteen years. As the story goes.

8. To draw lots, to soothsay out of an inferno, is simply not done. It reminds one of the Faust legend, or Robert Johnson’s railroad deal with the devil. Like a Oujia board for literary nerds (or, more properly, “bibliophiles”), a variety of sortes tempt many.

9. But The Cantos beckon. Suck a poor poet into their orbit. They are sirens. Robert Frost mentions, in a 1960 interview with the Paris Review, how Ezra Pound practiced jujitsu on him in a restaurant. “So I stood up, gave him my hand. He grabbed my wrist, tipped over backwards and threw me over his head.” Like its writer, the poem practices a similar sort of action on the reader.

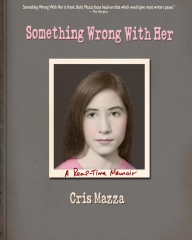

Something Wrong With Her

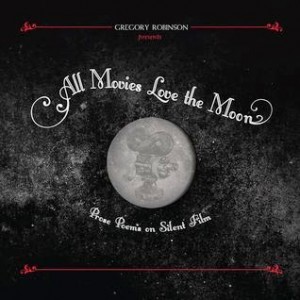

Something Wrong With Her All Movies Love the Moon: Prose Poems on Silent Film

All Movies Love the Moon: Prose Poems on Silent Film