Random

A little street

A rare Vermeer painting “The Little Street” (c. 1658) shows the side of a street in Holland spotted with a cast of the painter’s usual subjects, who may be taking a break from their role at the windows above. His sole painting of this nature, nobody knows why, that day, he decided to leave his room and paint from outside. Some art historians suggest that the scene in entirely imagined. I imagine the daylight, however dimmed by the clouds, entering the black windows — the soft angular light, the new shapes presented, and the intricate narratives unfolding inside. Neutral Milk Hotel’s “Holland, 1945,” which begins the only girl I’ve ever loved/was born with roses in her eyes/but then they buried her alive/one evening 1945 may well be about Anne Frank, her legacy one of edifice: of her building, of the bookshelf that led to her secret annex, the published cover of her diary proposing how one might look at it. This one sees her in her room, the way Vermeer would have imagined, reading a letter from a boy, or writing one; and while history congratulates composing letters, decomposing bodies has the final say. Buildings haven’t changed much in Holland, at least I’m guessing. I’ve never been. Who needs Amsterdam when you have rush hour traffic jam in front of you. At a red light, I imagine things in a glass room moving in an anthropologically sound way. We list our wars I and II, as if we were counting on something.

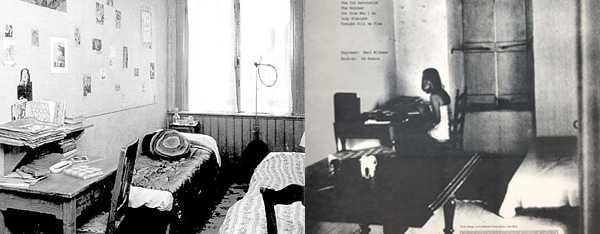

After I graduated from college, I moved into a rooming house shared by Asian students abroad, and one elderly man whose children, if he had any, either didn’t care or couldn’t afford senior housing. I’d often see him in torn ratty underwear coming out of his room with a tupperware drinking container full of piss, on his way to empty it out in hopefully the toilet, not the sink I brushed my teeth in. He’d stare at me viciously, in retaliation for the shame my gaze unwittingly incited, and I would lower my eyes. My window faced west towards the ocean, on Hwy. 1; it was a month-to-month lease which went that way, one barely noticed month at a time, for four years. The plan was to make more money, get a better place, have a better life, but I was quickly tossed into the lower-rung ladder limbo of the corporate world. I answered phones, quit, got fired, then answered them again. I would have preferred not to, but Bartleby might have sued (probably not). Black car exhaust mixed with salted fog embedded itself in the window screen, then gradually into my room. A crack in the wall between the tiled shower and my room birthed black mold which my lungs soon hosted, and I developed an odd guttural cough whose resonances seemed offered from the heart, as if finally breaking its silence.

One may choose the preserve things they way they were, behinds panes of thick glass — as they do the Mona Lisa (c. 1519, Louvre, Paris) or Guernica (1937, Reina Sofía, Madrid). Tourists desperately take pictures, drowned by their own reflections. Glass, being fluid, is a rain in front of you that never ends. Beauty may be the impossibility behind the tempest. Anne’s array of photos on her wall are displayed like the latest smart phone commercial showing off all their apps. Our idea of her, as some asexualized historical muse, is never completed. If one’s room is a spacious luxury coffin, then, to borrow from my favorite zen saying: live life as though you are already dead. In vivo post mortem, I listened to Leonard Cohen’s Songs from a Room (1969) on constant those years, borrowing Marianne, gently seated at the typewriter, for my own use. Every night I lit one candle, emptied a bottle of wine glass at a time, and sang my lesser version of the album. Empty green wine bottles aligned my window sill, displayed for the north- and south-bound world, until a note under the door from my landlady advised me to take them down. She wasn’t running some harem, it implied. If only she knew the whores were only in my mind.

The letters in Vermeers have narrative significance. They are either being composed, sent, received, or read. Texting killed the email and email killed the letter, but the letter lives on, the one you wrote to the one you loved, slid in the slit of their locker, waiting for the jury of unsmiling teeth. Some have offered that Vermeer’s letters are the discourse of courtship; others say they are the solemn correspondence between distant loves. Lustful love brings a patter to the heart; love, real love, is exhausting. Marianne sits at Cohen’s typewriter, and I imagine what she might have been typing, in courier 10 pt no doubt. And the letters to herself that Anne wrote, for publishing’s greatest posthumous account. Certain “eager” historians, oddly, argue that many of Vermeer’s women are pregnant, attributing this to their vague puffy apparel. It’s kind of sad how life continues, how the massive searing pain of birth isn’t a hint of what’s to come.

Hwy. 1 goes through 19th avenue in the Sunset district (named such for the theoretical setting sun, which you can’t see through the fog). I didn’t have a fridge or any food in the room, so when I got hungry, I walked down to the gas station for a bag of “original” Lay’s (this was my only way of getting laid). I would think of Van Gogh’s first serious work, “The Potato Eaters” (1885), of a humble peasant family under a dim light eating the potatoes they just spent 10,000 calories harvesting, and how easy and undeserved my imminent 600 calories were. As life gets better, it gets worse. One night, I passed the old man on my way down to the gas station. He had just gotten off the train, miraculously dapper in a 3-piece suit still redolent of the moth balls which kept it safe. He looked at me viciously, and I lowered my eyes. Sometimes a truck hauling redwoods from Oregon roars down 19th avenue as a kind of angry tied-up forest, shaking my room, and the little black spores inside my lungs. It’s like the beginning of WWIII, so loud, of planes overhead. “I lived on a fucking highway,” I say whenever lack-of-cred calls for it, but really it’s just six lanes and two directions to nowhere fast. It may have been raining that night, or the fog so thick, a clammy frozen slow-motion tempest, low as the under belly of a whale. The ways we accept how we live. After we passed each other, I turned back at a safe distance and looked at him. He had unzipped his fly, taken out his shriveled penis, and was pissing in the street. Finally, I got a smile.

the thing about Anne’s photos on the wall and iphone apps startled me

I like these pieces where you mix famous paintings, your life, music (often enough Leonard Cohen) and sadness/inescapable suffering of life. Don’t know if you read an LA Weekly article abt one of Cohen’s muses who was homeless in LA later in life. Here is a link to a random blog I googled that pasted the content from the article. http://drhguy.posterous.com/what-happened-to-suzanne

Nice job, Jimmy Chen. Loved this.

That’s a hell of a story, and Immediato wrote it well. A nice companion to mister jimmy’s vermeeriana (though I think each of his paintings is pretty dense).

“A crack in the wall between the tiled shower and my room birthed black

mold which my lungs soon hosted, and I developed an odd guttural cough

whose resonances seemed offered from the heart, as if finally breaking

its silence.”

“Sometimes a truck hauling redwoods from Oregon roars down 19th avenue

as a kind of angry tied-up forest, shaking my room, and the little

black spores inside my lungs.”

Yes and yes. Nothing but net here, Jimmy.

TYPICAL MISOGYNISTIC CRAP YOU ADOLESCENT PIMP

Uh, I think you should stop–you’re making us look bad.

Its beautiful JC