Random

Ad as friend

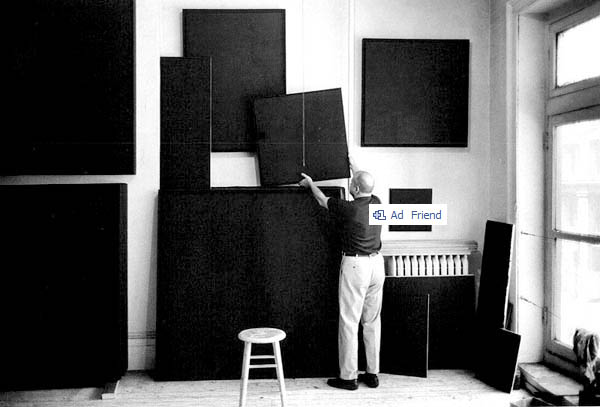

That Ad Reinhardt (1913 – 1967) is considered an abstract expressionist is odd, considering his paintings don’t drip, splatter, or explode the way his peers Jackson Pollock, Franz Kline, Willem de Kooning’s paintings did. Of peers, we may follow our way back to Malevich (quote, “I felt only the night within me”) and the Russian Suprematists during the first world war. As Stalin grew in power, the Russian avant garde’s anti-state realism inaugurated much of art’s underlining antagonism today. Ad found himself in the final stages of modernity. Warhol was already making the rounds, and times were a’changing…every 15 minutes or so. Dressed like a dad waiting at the mall, he Tetrises his studio with essentially the same painting, filling up the patches in his quest for night during daytime. A philistine might call it bunk, then go on to watch Judge Judy, as if then, the world made sense again.

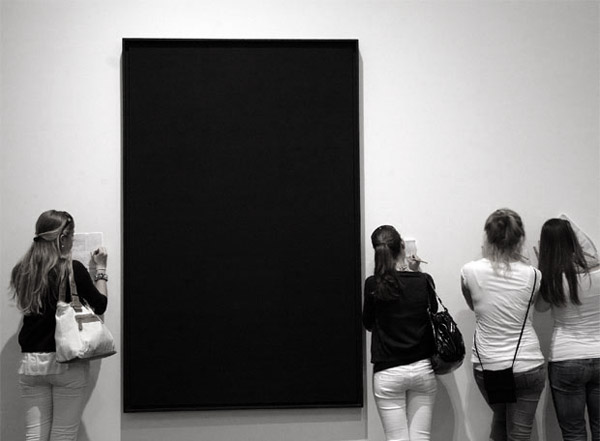

Ad’s paintings borrow the room’s light in which they hang to portray their space, and part of this room is you, whose migration from one end to the other receives different hologramed angles of light by which the canvas is seen. Ad paints his black paintings in a grid, applying the paint with alternating direction, brush strokes, and alchemy (e.g. medium, glaze, varnish) such that the spacial assertions are defined not by differing color or tone, but at what degree they are seen. Art theorists could attribute this philosophy: perception mistaken for intrinsic form. Painting, ever archaic, thrives off its very constraint; it’s amazing what people will do to a canvas. It’s amazing how much they can cost.

Ad’s paintings borrow the room’s light in which they hang to portray their space, and part of this room is you, whose migration from one end to the other receives different hologramed angles of light by which the canvas is seen. Ad paints his black paintings in a grid, applying the paint with alternating direction, brush strokes, and alchemy (e.g. medium, glaze, varnish) such that the spacial assertions are defined not by differing color or tone, but at what degree they are seen. Art theorists could attribute this philosophy: perception mistaken for intrinsic form. Painting, ever archaic, thrives off its very constraint; it’s amazing what people will do to a canvas. It’s amazing how much they can cost.

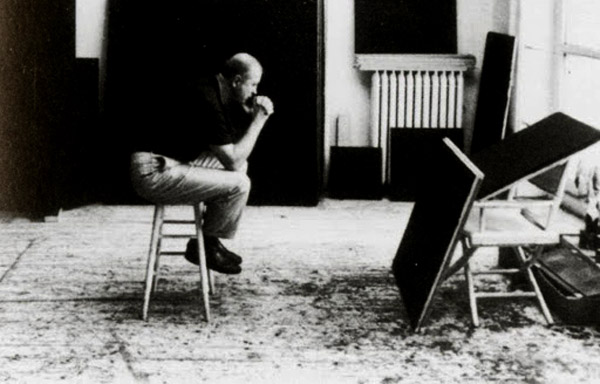

Every painting class has a moody guy who isn’t nice — not to say he’s effectively mean, in fact he’s relatively bearable compared to many of this classmates — just that he’s, well, literally “not nice.” He may wear nothing but black t-shirts, just a jagged logo short of being in a death metal band. Let me say here that I was not that guy, whew. Friday and Saturday nights — profound possibilities of collegiate experience augmented by their very indiscretions — found us both in the painting studio, an incandescent box of light situated deep in a redwood forest, some blocky tumor of youthful hubris. When my dad dropped me off at the dorm the first day of my freshman year, he somewhat indignantly told me to enjoy my four year vacation. I guess I did. I was in my de Kooning phase, juvenile anger confused for modernist solemnity, slicing away with my palette knife at a gooey-goopy woman I was trying to both render and deconstruct. Mister moody had been working on a large (6×6 ft.) canvas, and by working I mean painting over in mars black over and over again. Mars was a perfect name for a color; this guy was clearly not happy on earth. His favorite thing to do was ponderously sit in his chair and stare at his large canvas. Most of me thought it was ridiculous, but part of me envied him: his commitment to a delusion that this black thing meant something.

“There is no such thing as a good painting about nothing,” goes Rothko, oddly, since some may see his paintings as nothing, just a pretense of light, which gets us into the hairy problem of what something and nothing is, the subject and object, the subjective and objective, the form vs. content thingy which has sustained liberal arts eduction for generations. I remember looking intensely at an Ad Reinhardt (titles are less important than their creators) at the Whitney Museum in New York, a ponytail (back then, and sorry), some evocatively paint splattered shoes, thin legs smugly crossed, and one haunted hand over lips tightened in deep concentration, as if unleashed into some black hole, the beginning or end of the universe itself. A touristy midwesty man stood there looking at my museum theatrics like he wanted to slap me. I believe he actually shook his head in disbelief. Who do you think you are, his hard-working American eyes on vacation said, almost wet with pain. Oh, I’m just another art asshole, I in turn said. We both felt better. The world, having judged and been judged, made sense again.

Every summer art colleges release precocious creative people with artist statements in chronic revision into this world. The biggest lesson you learn in college is its graduation, the fine punch in the face you receive — the suburban overweight moms standing in grocery lines you unfairly resent, the town you grew up in which hasn’t changed, its stagnancy an indictment of perhaps your own, at least you fear, so you dive head first and money last into the nearest city, to become nothing more than a mouth to feed and rent suction. Buy food, pay rent is a true manifesto, yet sadly unworthy of a pre-coup trip to Kinkos. Still, you dress like an artist, so that’s good. A year or two later the rock shows you go to seem to begin later and later; the people sweaty next to you more and more annoying; the cool people on stage just kind of noisy and dramatic. You get a job that pays more with more responsibilities. What you thought you loved, who you thought you loved, these things still reside in you, just more pallid, almost cordial. One day you buy something from Pier 1 imports. One day you aren’t special anymore, despite what your relatives, instructors, and even friends said. One day you wear beige pleated slacks. One day you fucking look like Ad Reinhardt. All the boring people you once pitied getting excited over some television show you now despise, for that is you. Turns of the holy triangle is a rectangle, and it’s not a canvas, but the TV. I was once convinced I would die in a tiny apartment with syphilis, one ear, and 10,000 paintings in my closet. I saw my name in the Modern Museum of Art. Turns out it was just my ass in the gift shop.

When an attractive woman looks at a great painting, or heralds a great novel, or holds her hands in tween prayer doing that little happy bounce of excitement in the front row of a show at the first chord she recognizes, a million young boys with no chance will know what they want to do with their lives. (If this seems reductive, well, that’s what I’ve been reduced to.) Mr. Moody wasn’t crazy for covering a large flimsy rectangle with a canvas wrapped around it in black oil paint over and over, over the course of three months, the redwood rain tapping as light percussion from above. He wasn’t crazy for wanting what I wanted. We simply wanted attention, the best kind, in its most austere form: on a huge wall adorned with a plexiglass placard parenthetically citing the year of our death. If a novel is a man’s overwritten elegy, a canvas is his flappy tombstone. Immortality is a mortal man’s mindfuck. All the girls we never kissed those nights, their vodka in red plastic cups, in their bellies, finally back up on the carpet, the parties we were too scared or arrogant to go to, ensconced in our freezing studio, the gentle brass whine of Kind of Blue…kind of over it dude…I would never say; the wayward smiles given on streets, but unseen, our faces buried in cups of coffee; all that simple love, however stupid, that makes a human being simply feel wanted and accepted. These things owed him, owed us, would be ultimately marked and commemorated, first in pencil, then in an MS .doc, then in black toner, and stapled two hours before Art History 101, set in 12 pt. Times New Roman and double-spaced to make room for errors. Imagine a red pen excising with an angry loop a young girls’ impulsive “he was a genius,” the professor smirking at such pretension, maybe even a tad jealous. Imagine two guys in a studio, miles from Miles in his studio, themselves kind of blue, trying to win at art where they were failing at life, falling into the weave of their canvases as a replacement for someone’s arms. Something tells me we hated each other, for being each other. As for my women, I kept moving them around in a slow motion dance until they dried. Old and ugly, they were now ready for Dorian’s attic, but instead I hung them in a cafe → they didn’t sell → and I gave them to friends. If you have an artist’s not-so-settling-to-look-at painting hanging in your home, one that may frighten a guest or two — or a large black square whose creation meant for its creator so much that its very blackness may indeed be the unbound starless universe meant to contain all those feelings, all that love, and all that loss he would slowly come to realize — then you are a beautiful person. A real friend, someone who may even dust the canvas once a year. Thank you for keeping the dream alive.

Tags: ad reinhardt

“What you thought you loved, who you thought you loved, these things still reside in you, just more pallid, almost cordial.” <– That is some assassin quality word choice right there. Nice work, sir.

I was in art school with the guy in the black t-shirt except he was actually 59 nice, intelligent rich people who now live in large metropolitan areas and either make art or don’t but run their lives like businesses. So I still want to be him. Good work, though. Art school for real.

More like this, please!

This was absolutely beautiful. “A million young boys with no chance” and I thank you. Truest words I’ve read all week.

jimmy chenny is my own favorite write today, i have been that father waiting at the supermall, and I am a fan of oddity painting like chenny, i feel we are similar and both alive in the same century