Random

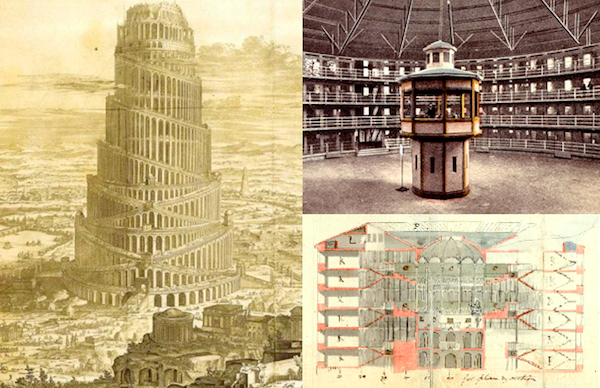

Babble on Babylon

“Go to, let us go down, and there confound their language, that they may not understand one another’s speech,” says the ticked off voice from above in the Book of Genesis (11:7) — though modern versions prefer confuse to confound, retroactively auspicious, since Babel sounds like the revised “confuse” (bālal) in Hebrew — thereby scattering our tongues into various, um, babbles, from the harshest Cantonese, bluntest Ebonics, to the always DTF-French. Regarding the etymology of babble, “no direct connection with Babel can be traced; though association with that may have affected the senses,” attests the Oxford English Dictionary. Near bizarrely, the original English word for babble was babeln (c. mid-13th century), that helpful -n a kiss away from Babylon, just for funnies, where this all supposedly took place, meaning “gateway to God.” Early 19th century philosopher Jeremy Bentham conceives the Panopticon, an institutional building (usually prison, though also applicable to hospitals, daycare, etc.) in which authorities at an omniscient center have a 360° view of the entire perimeter. Mr. metaphor Foucault (in Discipline and Punishment, 1975) is moved by the idea of “permanent visibility,” a form of power whose construct was more imperative than its actually being possible: the prison guards, while having access to the sweeping perimeter could only look at one area at a time, their backs turned to everything else. The habitual possibility of being watched was just as effective as actually being watched. Hence, religion as security cam.

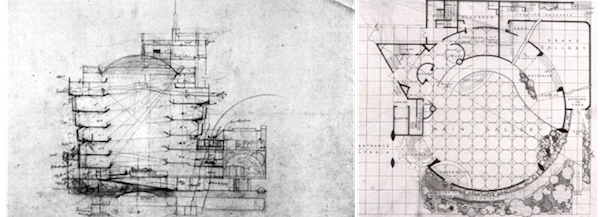

Frank Lloyd Wright, who was commissioned to design the Guggenheim Museum in 1939, conceived it with Babel-esque human hubris as a “temple of the spirit,” its structure ribboning upward and outward, each level wider than its base. (Those of you who hung around Fifth avenue/88th St. in the upper east side may have heard a handful of languages.) The Guggenheim Foundation at first dedicated it as “The Museum of Non-Objective Painting”; meaning, in a simplistic sense, paintings without objects in them i.e. abstract. Though it gets tricky since abstraction posits the objective (truth; form) over the subjective (senses; content), so in a way it sh-/c-ould’ve been The Museum of Objective Painting. Wright comes up with the word “Usonia,” to describe a New World-y American landscape and architecture, which likely came from “Usono,” the name for the United States in Esperanto, from Latin, with an extra c, g, j, and u (2nd versions accented) in their 28-letter alphabet; it belongs to a group of International Auxiliary Languages (IAL) including Arabic, English, and Spanish, the waft of past imperialisms taken for granted in their universal speech.

Solomon R. Guggenheim initially made his money in Alaskan gold and becomes butt-rich after a handful of good business moves. In that classic $-doesn’t-buy-happiness maybe art will, he drops everything, starts collecting objective paintings w/o objects done by grumpy 50-year-old men that probably could have been done by merry 5-year-old girls. The building shares the logic of multi-level parking lots, basically an ongoing gigantic ramp save the color coded floors. I went there once and felt like fecal matter contributing to its colon-like constipation. (Speaking of piece of shit, Matthew Barney, using wall climbing apparatus, climbs the Guggenheim in 2003 in unison with Cremaster 3, bringing in the new aesthetics of varsity art-bro.) It’s easy to get lost there despite the watchful eye of other patrons checking out your taste by the objects or paintings you stand in front of the longest. Taste is a prison. The museum security guard — minimum wage immigrants whose intense almost emphatic disinterest in the art they’re protecting is thrilling to watch — is perhaps the greatest “cultural artifact” in any museum. The sincere hell of their chronic boredom is at once existentially profound, socioeconomically upsetting, and quite contagious. I too almost fall asleep. I want to buy of postcard of them and take them home.

Circa 1563, Pieter Bruegel the Elder — not to be confused with his two sons Pieter the Younger and Jan the Elder; also his grandson Jan the Younger, all worrisome and tedious painters — paints “The Tower of Babel” and “The ‘Little’ Tower of Babel” (not qualitative, merely of smaller dimensions). The larger and implicitly more formal painting seems carved out of bedrock, of quarry in nature, as if excavating our intrinsic hubris. Little men in tents and on ladders going into secretive doors in which plans for heaven were being made. Most renditions of the tower of Babel are pristine, perfectly symmetrical as an inward fractal moving up. Pieter’s is rugged, seemingly made in error. On September 11, 1941, just a few months before Pearl Harbor and Roosevelt’s WWII response, the United States began construction of the Pentagon. Comprised of five facades A-E, going inward, E is the least accessible and most secretive. The idea was to have a shrinking correlation, despite being the same shape, between floor space and exclusion; outdoor courts separating the facades were connected by a complicated system of corridors to which only senior officials were granted access. The conspiracy theories on 9-11’s attack on the Pentagon ask WTF happened to the plane, the edifice’s virgin hole of apparent immaculate conception. A senseless world — its history perennially chiseled by senseless acts — oddly begets the placating tyranny of sense: the reasonable argument that tells you you’re a whack job if you watch youtube 9-11 conspiracy videos until 2:00 a.m. on Saturday nights, just sayin’. Things which may have happened are demoted into myths. Back in Arlington VA, little firemen comb the grass looking for evidence. News cameras, as vultures, arrive while the dead are still warm.

Babylon was in modern day Iraq, in the city Hillah some 5o mi south of Baghdad. It lies between what was the fertile crescent, between the Tigris and Euphrates. From the Ottoman and British Empires, to Saddam Hussein’s rule, to U.S. Militia, Hillah has seen its share of death. It’s a mass grave. “Allāh” seems more intuitive than the harsh Germanic “God,” the former’s alliteration with Mama almost infantile, as one imagines lips puckered at a swollen nipple the size of a gummy drop. Stanford neuroscientist Robert Sapolsky describes religion as “organized schizophrenia” (hearing voices, answering them) and OCD (ritualistic prayer; preoccupation with numbers; anal retentive food preparation), what he terms “metamagical thinking,” going on to say that diagnosed schizophrenics and charmers Marilyn Man卐on, D✡vid Koresh, and Jim Jones simply failed at the PR. Cults just need a greater ad budget. “Al-lāh” actually means “The God,” whose definite article is so certain may it rise above the rubble. We all remember — and eerily mock, with a tinge of contradictory racism — Rodney King’s “can’t we all just get along?”, a rhetorical question which simultaneously operates as earnest. King would be awarded $3.8M in a civil suit against the LAPD, marrying one of the jurors Cynthia Kelly, who allegedly found him just two months later dead in his swimming pool from accidental drowning. Those who think Kelly had a hand in it are told to consider the marijuana, cocaine, and alcohol found in his blood, substances which evidently can’t just get along.

An infidel’s journey (mine) into the Bible is full of weird life lessons. Genesis 11:8, next line, goes “so the lord scattered them abroad from there over the face of the whole earth; and they stopped building the city,” and I imagine the internet as a kind of Mesopotamia, a land “between two rivers” i.e. facebook and twitter — selective facial expressions as emotional braille for the blind; the self-exile of hotmail or AOL; the permanent visibility of a green “available” gchat icon as the updated light of “orgastic future” which Gatsby saw across the waters. I don’t understand you anymore, you tell the anthropomorphized internet whose social entropy you take personally. This may be spiraling out of control, pokes from strangers and unfriends from in real life friends. How could a building collapse so perfectly, almost peacefully resigned — asks any reasonable person of the twin towers. Given the expectation of chaos, sudden harmony is confounding. The buildings puff like a bong hit, then fall into retroactive reverie, as if we never dared trade in multiple currencies whose foreign exchange rates — of numeric systems immune to language — still ebb and flow with uncanny emotion. I’ve always enjoyed looking at the office paper falling from the towers, wondering what was writ on them: a desperate resume printed out on low toner; a cassoulet recipe for that evening; a bad poem after a good date; an inconsequential threat from an obsolete job. Google translate can “detect language,” but only in verbatim. Idiom, it seems, is the game of idiots. If there is such a thing as eternal peace, it can probably be viewed from every angle at once. The cubism of heaven. Bruegel, formerly Brueghel, drops the “h” in 1559 because what the ell. He and his sons, each one less and less famous, die. A painting as a postcard pierced by a thumbtack to a wall. To trace it through pixelated falling debris is to grasp for a pattern so uncertain, so unique to itself, it may as well just be falling.

babble on, babylon

highly-charged political think-piece

i always enjoy your writing, but i kept wondering where you were going with it. was this like ‘start with genesis and see where it takes me?’

but anyway jimmy chen i love you and wanna make sweet love to your gilded prose

i enjoyed this; thoughtful and good and fun and smart