CENTERPIECE

CENTERPIECE

by Daniel Muehlmeier/Lee Mothes

Warm Wax Inc., 1991

2 players / 30 minutes / $19.99 from eBay

CENTERPIECE is a board game designed by Daniel S. Muehlmeier, self-described “unlocker of secrets,” with art by Lee Mothes. It was taken off a Goa’uld mother ship.

You won’t find CENTERPIECE in the Toys & Games section of your local Barnes & Noble. The game, originally published in 1991, is a notoriously tough sell. “I do well in the twenty-dollar range,” said the author in his recent Kickstarter campaign, which managed to raise only $615 of funds from 23 backers. “I keep a few game boxes in my cars back-window. Creating sales proved tough for me.”

“One restaurant placed five games. Near where people pay. All five disappeared, I never even restock them. Example of really bad-marketing skills. Yet I’m really looking forward, to direct mail to customers.” Following the close of the Kickstarter, the game is now being listed on eBay under the heading “tradition game, toys and Hobbies.” Yet this is just a stepping stone for Muehlmeier, who would eventually like to see his game displayed in a contemporary art museum.

Nor is this a delusionary ambition. Bad-marketing skills aside, Muehlmeier’s creation intrigues; in fact, it’s best approached from the vantage point of art (as opposed to game) criticism. Even taken as a game, CENTERPIECE is an answering shot to the pet theory that the whole of a game’s value rests within its mechanical core, for which the superficial elements of theme and appearance serve as mere window dressing.

CENTERPIECE‘s mechanisms of play are invitingly familiar. In fact, CENTERPIECE could accurately be called a pastiche of several games known to all American children: Monopoly, Parcheesi, Chutes and Ladders. Pastiche in both senses of the word, since CENTERPIECE‘s core mechanisms walk a tricky line between quotidian simplicity and schizophrenic montage, made no more easily reconciled by the often indecipherable rules, which read like an antique riddle. “Players are encouraged to use common sense,” the single-leaf rules advise. “For example, if both players are sent to the Bird Cage; because a player rolled a two, while visiting the Honey Jar space. The player who rolled snake-eyes would roll for doubles first. Both player would stay for three turns, unless doubles were rolled.”

Once mastered, CENTERPIECE is an almost fully luck-driven affair, a roll-and-move game destined to be despised by the modern board game community, who have become spoiled by worker placement, economic engines, asymmetric player roles, and all the other innovations the last two decades have brought to the medium (remember, CENTERPIECE is a time capsule from the early ’90s, although aesthetically, it hearkens to an even earlier era). Yet the game’s “superficial” elements are not to be discounted, for they create a metaphorical frame or structure as the game plays out, turning a simple reimagining of Monopoly into something that far exceeds the sum of its parts.

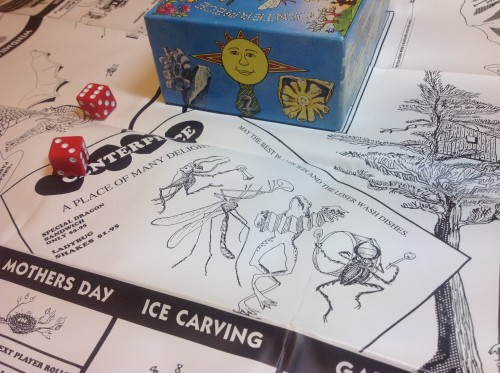

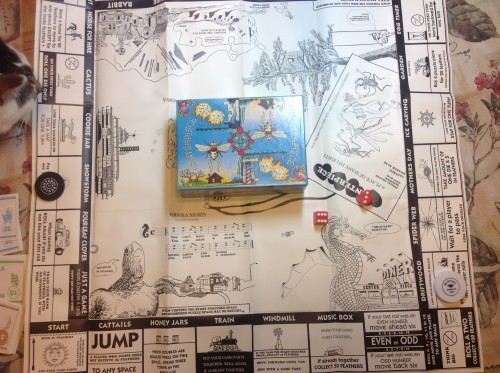

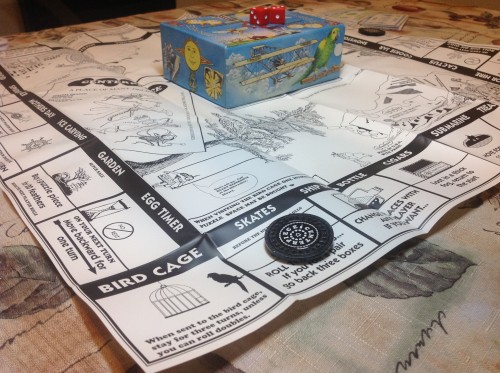

As if to embody this very statement, the first bread crumb along CENTERPIECE‘s allegorical trail is the fact that the game’s box, colorfully illustrated by artist Lee Mothes, is also central—both literally and figuratively—to its gameplay. Once the board has been unfolded, the box top is placed at its center, a mechanically unimportant gesture that receives special emphasis in the game rules—and is hammered home with every turn, as the dice pounding off of its cardboard surface speak testimony to its substance (that the dice must be rolled off of the box top is another apparently superficial but ritualistically significant gesture). As the eponymous centerpiece, this raised rectangle of cardboard naturally draws the eye—it is the only spot of color in an otherwise black-and-white composition—while hiding the game’s deepest secrets. A display of puzzle pieces nestled beneath track the players’ scores, and it is to Muehlmeier’s infinite credit that he keeps this indispensible information hidden away until the moment that the box is lifted, a moment that always coincides with a change in the data under scrutiny. It is the uncertainty principle actualized.

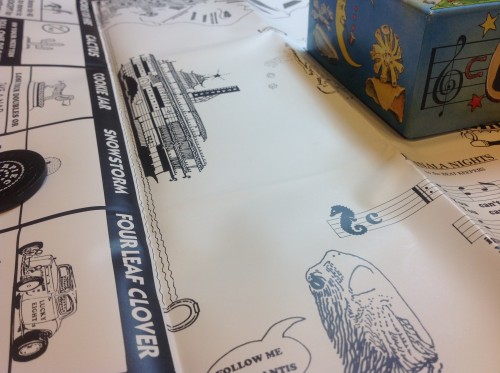

In his bio, Muehlmeier cites inspiration from Kit Williams and Paul Hoffman, both famous for authoring literary puzzles pointing the direction to real-life treasure. Perhaps it was this that inspired him to print CENTERPIECE‘s playing “board” on map paper, so that “it folds forever”–”like a new book,” the accompanying video explicates. This makes possible the recursive trick mentioned above, by which the structure containing CENTERPIECE is folded fractally into its own center. This cyclical immanence forms a bounding structure—not rigid, like the game box, but something soft and fluid, cocoon-like, that enwraps the players within the experience of the game.

Is CENTERPIECE a treasure hunt, along the lines of Kit Williams’ golden hare? A metaphysical one, if nothing else. Artist-collaborator Mothes has made a career out of painting dreamed oceanscapes from his Wisconsin home, as well as sundry other artifacts of the (wholly imagined) Commonwealth of New Island. This shared yen for legendary treasures and uncreachable spaces is more than apparent in the game’s lexicon, which ditches Monopoly‘s worldly materialism in favor of a set of evocations. Circling the board, the players collect feathers in lieu of money, in three denominations: seagulls, duck bills and eagles. They land on spaces marked Mother’s Day and Ice Carving, Cattails and Honey Jars. They can be submerged in a Submarine on one turn and trapped in a Spider’s Web the next. A literal description of the gameplay, from Muehlmeier’s Kickstarter page, reads like verse: “Dice fall off box, the game travels in. White and black poker-chips get pulled apart and put together.”

Even the white spaces of the board are rich with detail for the wandering eye to unearth between turns. From musical score (“Ishnala Nights” by the Beat Keepers, with lyrics such as “You can’t have fun or eat / an Iguana, unless you wanna”) to mountain trails to an oddly bug-centric menu, CENTERPIECE has more than enough to tantalize. And if it is no great evolution of tabletop gaming—even if its juxtapositions do not hide the secret to Muehlmeier’s next great discovery, a 36-digit number that is a possible new home for artificial intelligence—CENTERPIECE is no less worthy because of it. It is a transportative piece, a composition and a map that draws new connections between old ways of playing. And the less strategically minded the game, the more the players are free to simply be within its folds.

Muehlmeier’s own words, lifted from his Quora account: “I’m not sure where Puzzle Logic fits in the world. I do know that the more one puts it to use. The better a person gets at thinking that way. Its a freedom to use logic, to conect like objects, and see where they lead.”

***

Byron Alexander Campbell is a writer, editor and intermittent game critic. His fiction has appeared in Polluto, [out of nothing] and the Interactive Fiction Archive. Follow him at theyearisyesterday.

Tags: board game, Byron Alexander Campbell, CENTERPIECE, Daniel S. Muehlmeier

This is amazing.

There should be more game reviews at HG.

I might be able to help with that. ;)

[…] case you missed it, this is my second HTMLGIANT review of the month. The first was of Daniel S. Muehlmeier’s art object/board game CENTERPIECE, the subject of a failed and […]