CENTERPIECE by Daniel S. Muehlmeier

CENTERPIECE

CENTERPIECE

by Daniel Muehlmeier/Lee Mothes

Warm Wax Inc., 1991

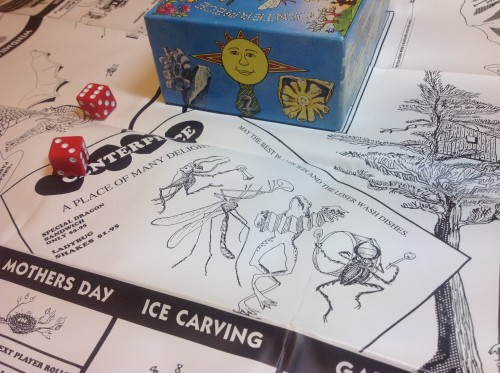

2 players / 30 minutes / $19.99 from eBay

CENTERPIECE is a board game designed by Daniel S. Muehlmeier, self-described “unlocker of secrets,” with art by Lee Mothes. It was taken off a Goa’uld mother ship.

You won’t find CENTERPIECE in the Toys & Games section of your local Barnes & Noble. The game, originally published in 1991, is a notoriously tough sell. “I do well in the twenty-dollar range,” said the author in his recent Kickstarter campaign, which managed to raise only $615 of funds from 23 backers. “I keep a few game boxes in my cars back-window. Creating sales proved tough for me.”

“One restaurant placed five games. Near where people pay. All five disappeared, I never even restock them. Example of really bad-marketing skills. Yet I’m really looking forward, to direct mail to customers.” Following the close of the Kickstarter, the game is now being listed on eBay under the heading “tradition game, toys and Hobbies.” Yet this is just a stepping stone for Muehlmeier, who would eventually like to see his game displayed in a contemporary art museum.

Nor is this a delusionary ambition. Bad-marketing skills aside, Muehlmeier’s creation intrigues; in fact, it’s best approached from the vantage point of art (as opposed to game) criticism. Even taken as a game, CENTERPIECE is an answering shot to the pet theory that the whole of a game’s value rests within its mechanical core, for which the superficial elements of theme and appearance serve as mere window dressing.

CENTERPIECE‘s mechanisms of play are invitingly familiar. In fact, CENTERPIECE could accurately be called a pastiche of several games known to all American children: Monopoly, Parcheesi, Chutes and Ladders. Pastiche in both senses of the word, since CENTERPIECE‘s core mechanisms walk a tricky line between quotidian simplicity and schizophrenic montage, made no more easily reconciled by the often indecipherable rules, which read like an antique riddle. “Players are encouraged to use common sense,” the single-leaf rules advise. “For example, if both players are sent to the Bird Cage; because a player rolled a two, while visiting the Honey Jar space. The player who rolled snake-eyes would roll for doubles first. Both player would stay for three turns, unless doubles were rolled.”

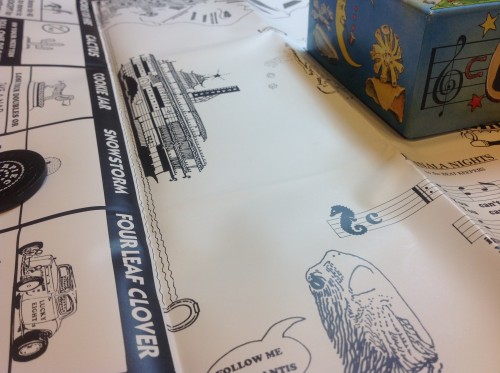

Once mastered, CENTERPIECE is an almost fully luck-driven affair, a roll-and-move game destined to be despised by the modern board game community, who have become spoiled by worker placement, economic engines, asymmetric player roles, and all the other innovations the last two decades have brought to the medium (remember, CENTERPIECE is a time capsule from the early ’90s, although aesthetically, it hearkens to an even earlier era). Yet the game’s “superficial” elements are not to be discounted, for they create a metaphorical frame or structure as the game plays out, turning a simple reimagining of Monopoly into something that far exceeds the sum of its parts.

As if to embody this very statement, the first bread crumb along CENTERPIECE‘s allegorical trail is the fact that the game’s box, colorfully illustrated by artist Lee Mothes, is also central—both literally and figuratively—to its gameplay. Once the board has been unfolded, the box top is placed at its center, a mechanically unimportant gesture that receives special emphasis in the game rules—and is hammered home with every turn, as the dice pounding off of its cardboard surface speak testimony to its substance (that the dice must be rolled off of the box top is another apparently superficial but ritualistically significant gesture). As the eponymous centerpiece, this raised rectangle of cardboard naturally draws the eye—it is the only spot of color in an otherwise black-and-white composition—while hiding the game’s deepest secrets. A display of puzzle pieces nestled beneath track the players’ scores, and it is to Muehlmeier’s infinite credit that he keeps this indispensible information hidden away until the moment that the box is lifted, a moment that always coincides with a change in the data under scrutiny. It is the uncertainty principle actualized.

December 4th, 2013 / 12:00 pm