Random

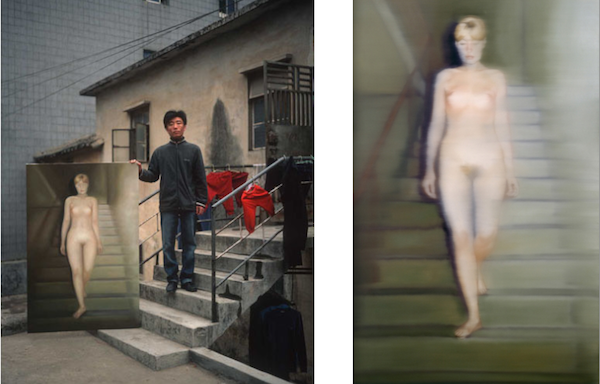

Nue Descending a Staircase, No. 1

When photographer Michael Wolf, as part of his “Real Fake Art” (2006) series, asked our Chinese copy artist to pose next to his copy of Gerhard Richter’s “Ema (Nude on a Staircase)” while being on a staircase himself, we might wonder if accidents are wonderment. The original painting (1966), shown right, is “better” in its purposeful degradation of oil paint’s capacity, by way of demoting it to flaws of the photograph: the blurriness, the bleached colors, the overexposure from the camera’s unconscious flash. For Richter, paint was a dumb thing, like toothpaste, whose only remaining relevance could be to pay tribute to photography. Of course, when he was in the mood. And his moods often changed. Short of any more research, I wonder who Ema is — his wife perhaps. The staircase is institutional-like, i.e. not domestic, and, if wonderment is still this siren’s call, I wonder where the hell they are. As for Ching Chong, should that be his name, may his time spent with Ema be clouded with the toxic high of turpentine, alone in his no doubt ventless studio, turning fake into real, or the other way around, for commerce, the sad advanced stages of Warhol’s once silly threat. Dude needs to take a large fan brush and go back and forth over the canvas left to right, wax on wax off, obscuring Ema into flatness like the shallow lens of a disposable camera.

Richter may have been nodding to Marcel Duchamp’s “Nude Descending a Staircase, No 2.” (1912), and yes, so much nodding in art history at times feels like nodding to sleep, but a bed is a boring place, especially for Regan, a 12-year-old girl possessed by Satan. The Exorcist (1973) was released seven years before Reagan’s election, so we’ll have to accept that Regan as Satan is merely an auspicious premonition. The still from the “spider walking” scene, at first cut out but included in the digitally remastered 25th anniversary special (1998), has been flipped in agreement with Duchamp’s orientation — left to right, the unconscious Western vector of forward progress — as coincidences matter less than this aggressive collation of moments into coincidences. Our siren, what was her name? Wonderment. Maybe she is dead. Maybe I’m thinking too hard, or not hard enough. Regan descending a staircase wasn’t originally included because of the visible suspension wires a contortionist stunt double used. Years later, CGI would give the devil its long awaited glory. It takes an asshole to honor himself, the auto-eroticism of being one’s sole contained muse (I am not talking about me). Duchamp gladly photographed himself (c/o photojournalist Eliot Eliofon for Time, 1952) descending a staircase, a multiple exposure marking the segment of time, the minutiae of moments, downward as a chill Sisyphus, until he turns his back on the camera, which any porn actress POV-ing head will tell you, is you.

“Nude Descending a Staircase, No. 1” exists only as an invocation of linear necessity, we counting on our ability to count. Duchamp understood this, his pawn always one square in front of us, one at a time, in its steady promotion to a Queen. It is little to say that chess is not just a metaphor, but a microcosm for life. With origins in the Islamic world for teaching infantry tactics, the invariable lessons of bloodshed went both directions to China and the Western world. If there are only 64 squares, and each opponent is forced to move after the other, then conflict is inevitable. Advanced chess players tend to group their pieces into islands, irregardless of the board’s initial orientation. They see the board from all four sides. The more sides you can see things from, the smaller the sides have to become, and you’re closer to a circle. Mediocre chess players, such as myself, will simply move forward, somewhat blindly, offering a bishop for a knight [3:3], or a bishop and pawn for a rook [4:5], if I think I’m getting to where I want. That the king is King is, of course, of the patriarchy; but the Queen is most powerful in her agility. I imagine her with blood dripping down her chin, a carnivorian menstruation from the mouth. This may be an unkind image — but unkind, unnamed, undressed, under my body, our worlds seem to get by. There is a general rule that the better player, he should, if given the chance, always trade Queens [9:9]; that without her on the board, the better player will win. The idea is that she is too easy too use, giving bad players a shot at the game. This is why I hold on to my Queen at all costs when threatened by a trade, retreating her into the crowded crevices of my side of the board. There’s something about a woman that makes you want to hold on to her for as long as possible. The oddly shiver-inducing world outside my body needs more than fleece or a cashmere sweater, but a large placenta on which to lean for the rest of my imbalanced life, she my bloody faceless conjoined twin. I would call her Nue, and she would have no choice but to walk down the stairs when I do.

bobbyroll: http://www.chessgames.com/perl/nph-chesspgn?text=1&gid=1008419

*Nude Descending a Staircase, No. 1

“I would call her Nue, and she would have no choice but to walk down the stairs when I do.”

http://vimeo.com/15959762