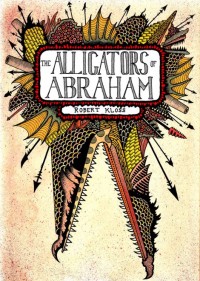

The Alligators of Abraham

The Alligators of Abraham

by Robert Kloss

Mud Luscious Press Novel(la) Series, 2012

214 pages / $15 buy from SPD or Amazon

1. Alligator: Non-commissioned submarine, completed Spring 1862 by Union Navy. Length: 14.3m. Speed: 2-4 knots. Crew: 8. Missions: Five, failures. Abandonment: Its tow ship, the U.S.S. Sumpter, cut it loose during a storm off Cape Hatteras, NC. Remains lost.

2. Abraham Lincoln visited the Alligator during its testing phase. Brutus de Villeroi’s initial design required paddle propulsion, which was later replaced by a central screw propeller.

3. (The American Annual Cyclopedia and Register of Important Events of the Year 1891): “One steamer, the ‘Louvre of Paris,’ was built and put on service [using a central screw] between Paris and London. She made a very good record for herself for nearly a year, but was unfortunately wrecked, through no fault, however, of her peculiar construction.”

4. When the alligators finally appear and begin devouring people about halfway through RK’s novella, I did one of those disorienting Google/library searches on whether a plague of alligators really followed the Civil War anywhere in the coalescing Union. I found the Alligator instead, and I couldn’t separate it from the flesh gators in the book. A plague of hungry submarines.

5. Matt Kish’s drawings are toothy reptilian sprawls of overlapping flesh and machine, gaping mouths in the process of being perfected.

6. The General, Alligators of Abraham’s marauding patriarch, shifts his bloodlust, augmented by grief over a son dead from typhoid and a suicided wife, into (self-)mutilating industry. Into a necrophilic fixation on embalming his body while still alive, and living inside the bloated corpses of alligators. Into pathetic need: “I need you here by my side. I fear I may destroy us all” (to his second son, after a second wife has left him). Into merging his sons’ identities, never naming the composite dead/alive child he (and the book) regards as you except to call him by the dead boy’s name, Walter.

7. Old Testament-fueled American novels of war rage relegate women to drawing rooms, brothels, graves, sanitariums, rumors, away. The second wife inspects a private room the General has customized for her, and says to son and husband, “Will the both of you just leave?” As if I can’t be in this room if you’re watching. And after she has packed and gone, the General says to his son, “If she weren’t gone already, I would kill her.”

8. “And your father lit kindling beneath his tin tub while infant alligators darted within, and soon the slow boil of water, and your father said into the absence, ‘I believe their hide impervious.’ And when these alligators bobbed lifeless in the bubbling, your father said, ‘They must become stronger with time.’”

9. (This Republic of Suffering: Death and the American Civil War): “Redemption and resurrection of the body were understood as physical, not just metaphysical, realities, and therefore the body, even in death and dissolution, preserved ‘a surviving identity.’ Thus the body required ‘sacred reverence and care’; the absence of such solicitude would indicate ‘a demoralized and rapidly demoralizing community.’ The body was the repository of human identity in two senses: it represented the intrinsic selfhood and individuality of a particular human, and at the same time it incarnated the very humanness of that identity—the promise of eternal life that differentiates human remains from the carcasses of animals, who possess neither consciousness of death nor promise of either physical or spiritual immortality. Such understandings of the body and its place in the universe mandated attention even when life had fled; it required what always seemed to be called ‘decent’ burial, as well as rituals fitting for the dead.”

10. Nobody in this book is decent.

11. Kloss structures time to allow peculiar slanted depictions of violence—overheard crunch of bone, blood flowing from open wounds, rats nesting in or birds/flies feeding on corpses—while frequently avoiding direct applications of force. Violence often is imminent or has just occurred, and violent actions are dreamlike and off-center. The things being done to human and animal bodies are atrocious, but his sentences slide past these atrocities: Mary Todd Lincoln holds Lincoln’s blood-spattered clothes (while readying them to be sold); a soldier writes home about being pinned under his horse, a “house of meat,” while bullets were filling its body (the letter does not appear); “And veterans fired rifles from their windows while their wives and sons lay maimed and rotting and disappearing into the bloody gullets of alligators.” Firing at what?

12. Robert Lincoln and the “millionaires” who seem to operate as extensions of Abraham collectively resemble Satan from Luis Buñuel’s Simon of the Desert, plucking you out of time in the third book and employing him in the endgame of a much more ancient scheme.

13. The use of “unpaid” and “paid” as nouns to designate slave and free is the book’s most pointed compression. “Slave” or “free” status in the United States is latched to a particular historical period and racial split. But the book glides past the moment of the 13th Amendment, and does not stop distinguishing between unpaid and paid. Multiple and persistent lines of mistreatment converge on the extreme compensatory unfairness that contradicts “defeat” of all forms of slavery.

14. War prepares the way for alligators.

15. Biblical/Torahic fragments contort the narrative. The epigraph is Job 14:1—“Man that is born of a woman is of few days, and full of trouble.” Another voice’s oblique intrusion at King James altitude churns with longing, death, wrath, ambition. Nearly too on-the-nose is the ominous repetition of a line from the Gettysburg Address after the Lord has appeared to Lincoln in a dream and demanded his boy Willie as a sacrifice: “This Union shall not perish from the earth.”

16. Perverse reaffirmation of the Abrahamic covenant: Lincoln walking between the ruined bodies of battle dead and the completed sacrifice of his beloved son.

17. The intruding voice as a chorus of the dead, but unlike dead voices still tethered to character corpses. The intruding voice that says Let us build a city and a tower, whose top may reach into heaven stands outside time, asking this to happen again and again until we are exhausted.

18. (Invisible Cities): “The catalogue of forms is endless: until every shape has found its city, new cities will continue to be born. When the forms exhaust their variety and come apart, the end of cities begins.”

19. Wars end when death exhausts its variety and comes apart.

20. (Wieland): “‘How almost palpable is this dark; yet a ray from above would dispel it.’ ‘Ay,’ said Wieland, with fervor, ‘not only the physical, but moral night would be dispelled.’”

21. The only answer to a prayer for mercy is Not enough death yet.

22. And if the voices of the dead untether from their bodies, no intrinsic selfhood nor individuality nor humanness bound up in a promise of redeemed eternity has any bearing on the body, before or after death.

23. Though each could be a Spirit, hovering over the waters.

24. Ready to speak the next Creation.

25. “And in the still of the vacant room, your father uttered, ‘I have been strange, I know,’ and he said, ‘I have not always been as I should,’ and he said, ‘There is something within that seeks to destroy me,’ and he gestured to the lawn of alligator parts, saying, ‘But I will cure our ailments.’”

Tags: 25 Points, mud luscious press, Robert Kloss, The Alligators of Abraham

yay peter!

Can I have your copy now that you’re done with it?