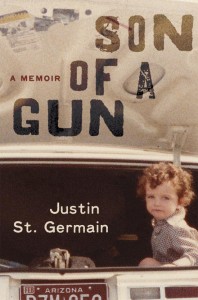

Son of a Gun: A Memoir

Son of a Gun: A Memoir

by Justin St. Germain

Random House, 2013

256 pages / $26 Buy from Amazon

As I read Justin St. Germain’s memoir Son of a Gun, I began circling all the times I came across the words “I wonder”: “I wonder why he never tried to call me, if he was ashamed, if he thought I was”; “I wonder where it is now, if she lost it, if I left it behind in the trailer”; “I wonder if she told him to say that, trying the same trick that worked on the judge who dismissed my case.”

The blurb on my copy’s back cover compares Son of a Gun to The Liar’s Club and This Boy’s Life, and while there’s certainly a likeness, St. Germain’s story isn’t so much as coming-to- age as it is remembering the moment he did—piecing together the events that led his step-father, Ray, to murder his mother with a shotgun.

At a cemetery, when St. Germain and some of his extended family fly to Philadelphia to bury Barbara, he mourns not the passing of his mother but the passing of his memory:

She fades a little more each day: I can’t picture her face, can’t remember a time when she was alive. I don’t know her story, because I’ve tried to forget, and because there was so much I never knew… Nearly a decade now since she died, and all that’s left of her are a few relics and my own suspect memories.

St. Germain opens, though, with perhaps the clearest memory he has: the afternoon he learned of the killing. Riding his bike home, he stares up at the expansive Arizona sky. It’s only been “nine days since the towers fell,” and he’s “newly conscious of planes.” When he arrives at his house, his brother, Josh, tells him the tragic news: “‘She got shot.’”

At a bar later that night, unsure of what to do next (“‘Wait, I guess’”), St. Germain drinks with his friends, watching President Bush address the nation on television: “He said that life would return to normal, that grief recedes with time and grace, but that we would always remember, that we’d carry memories of a face and a voice gone forever.”

Remembering “a face and a voice gone forever”—rounding out his “own suspect memories”—is what St. Germain hopes to solidify ten years later through his writing, and his struggle is not one of coming to terms with the tragedy (who can ever do that?) but of realizing that his recollections, his “truth” about his mother’s life, is what’s most important. That he starts with her death—that when he hears about what happened he doesn’t experience “shock” or “grief” but rather “a recognition, as if [he] had always known this moment would come”— presents an apparent contradiction: that one of his most vivid memories was formed even before it materialized.

Growing up in New Jersey, not far from Manhattan, most people I know can say what they had been doing on September 11th, while many also claim a counter-narrative, what they should have been doing, what they weren’t doing: they missed work because of a last minute disease; they didn’t get on one of the flights because of traffic; they decided not to take a day trip into New York that morning. I always thought there was a slight self-centeredness to such thinking—it could have been me, but wasn’t—and likewise, invoking such a large concept at the start, his mother’s death in the wake of 9/11, runs the risk of the same solipsism. St. Germain, however, does this so skillfully and so deftly that he’s completely changed my thinking, especially on the first matter. It’s not a selfish act for the could-have-been-victims of the terrorist attack to imagine if it had been them, or a loved one, or somebody they knew; instead, it’s a way to try and make sense of something insensible, even if it’s not completely shocking, or even, perhaps, if it’s already been there as a likelihood in one’s mind all along.

How St. Germain achieves such a feat—proving how his subjective memories supersede any “facts” about his mother and the culture of guns, violence, and abusive men that probably killed her—deserves the highest praise. As the narrator of his own story, St. Germain succeeds in blending his personal account with broader historical frameworks—most notably, Wyatt Earp’s famous duel at the OK Corral in the author’s native Tombstone, Arizona—by playing various roles.

First, of course, St. Germain wants to tell the story of his mother, and he does so with a restraint and a force and a particular beauty that’s all his own. For the most part, St. Germain remains an almost journalistic tone and method: he returns to the scene of the crime, at his mother’s trailer in the Arizona boondocks; he interviews all of his step-fathers, asking them their memories; he attends her funeral and church service, a scrap-booking support group, a gun show (in the hopes of buying the weapon Ray used); he drives around Tombstone, the small town America he left, and writes about the businesses and restaurants and stores his mother and her many boyfriends operated. There are overarching themes, ones of domestic violence, gun control, and the failure of the American Dream, that he can’t ignore, and he addresses them with a knowledge and a familiarity and an objectiveness that shows his tale is both personal and universal. That he finally recognizes “how it feels to live in a place like [Tombstone], the grinding poverty, the lack of opportunity, all the kinds of self-defeat—alcohol, drugs, gossip— the gnawing fear that you haven’t gotten away from the world, it’s gotten away from you” shows that he escaped a nightmarish fate. Because what he doesn’t go as so far to write is that the “world” in Tombstone didn’t get away from his mother, but that it bred the man who pulled the trigger.

St. Germain’s a journalist, then, but also a gifted writer (a former Stegner Fellow), one with a grounding of place and characters and conversation, and one, too, with a reliance on the old masters. When first writing about his mother, in these diary-like entries he entered on his computer, St. Germain quotes Henry James’s “The Beast in the Jungle”—“My mother is dead. The Beast has sprung.”—and later, he thinks of Hemingway’s “A Clean, Well-Lighted Place,” a dialogue-driven story that revolves around a failed suicide, written by an author who ultimately committed suicide. To say St. Germain is suicidal might be stretch, but to say he often feels an overwhelming sense of loneliness, like the deaf old man in Hemingway’s short story, would be nearer the truth.

Much as Hemingway’s deaf old man, too, St. Germain hides in the shadows of his tale— as a well-read researcher, an investigative journalist, a fiction writer, a mythologizing historian— so when he does step into the light, so rarely, it’s a blaring display. In one telling anecdote, St. Germain shares a time his mother “flew into a summer storm on a solo flight” (she went to airborne school at thirty, after being in the Army) and fearing a crash, she had sent her sons “a message through the air: Boys, be strong. I love you.” Later, when asked if he “heard her message,” St Germain tells her the truth: “I hadn’t heard anything.”

He may not have heard anything at the time, and he’s the first to admit that he won’t actually ever hear anything, but that’s not the same as imagining “one day [he] would hear her voice again, and know that she had never left [him].” It’s not the same as never knowing what really happened: that, despite the interviews and research and the historical scopes that preoccupy him, St. Germain will never know Ray’s last thoughts, just as we’ll never know those of the men who hijacked the planes.

What matters, in the end, is when St. Germain steps into the light, when we wonder, when we think what happened if that was us—what happened if it had been our mother, or our son, or our friend—and everything else fades into the shadows: the old man walks home drunk, and we’re left not with any sort of understanding but a voice, an image, a moment, that never fails to shine.

***

Alex Norcia is a writer living in Brooklyn. He has words in Word Riot, The Rumpus, and The Florida Review, among others.

Tags: Justin St. Germain, Son of a Gun