All Movies Love the Moon: Prose Poems on Silent Film

All Movies Love the Moon: Prose Poems on Silent Film

By Gregory Robinson

Rose Metal Press, March 2014

96 pages / $14.95 Buy from Rose Metal Press or Amazon

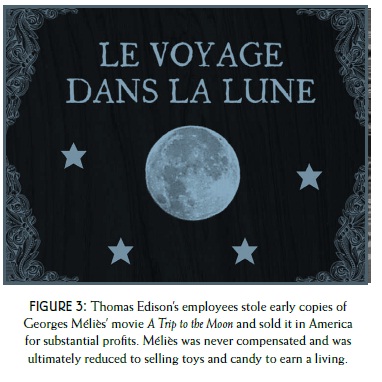

“In 1894, Fred Ott sneezed. Thomas Edison’s cameras were there to transform the event into a motion picture, appropriately named Record of a Sneeze,” So begins moving pictures, and Gregory Robinson’s brilliant new meditation on silent film, All Movies Love the Moon, out now from Rose Metal Press. In this work, he juxtaposes frames from silent pictures with musing prose poetry. He explores works by the Lumière brothers, Georges Méliès, and Fritz Lang. Just the filmography he provides is fascinating, especially if you’re like me where these films have always chiefly evoked classic Smashing Pumpkins music videos: Méliès (Tonight, Tonight) and Lang (Stand Inside Your Love).

Like Simic’s treatment of Joseph Cornell, Robinson brings a poet’s eye to the project. He employs information,misinformation,history, and histiography; and the result is often very funny, offering up strange errata and juxtapositions.

He tells the story of Ralph Spence, a “film doctor” responsible for taking unfunny early films and making them watchable, by writing witty title cards.

And he catches the chimerical, and hysterical aspect of the early theater experience:

Before you, a dirt road. A carriage passes, then a cyclist, both stirring a cloud of dust that settles on an automobile. The car is far angrier, making mad s shapes in the road, darting forward like a shark. Logic says move, but you have grown too heavy in this dream and the car is impossibly close. It breaks out of its world into yours, a pharaoh crossing over, a moth errant unto light, and Oh mother will be pleased.

A pause. Here is death, an old woman whispers over popcorn. I knew it would happen like this. In movies mortality makes your acquaintances, inscripting your bones.

Early films held terrible and novel power. Scenes of disasters and tragedies, captured in irreproachable fidelity via telescopic lens, brought viewers closer than ever before to the spectacle of ritualized death. And with the transference of Gothic / and German Expressionist aesthetics into cinema, this horror only deepened. Film became a playground for the supernatural:

“Of their own volition, creepy knives cut sausage and stack it neatly. Magic scissors cut hair, magic razors shave chops. Director Segundo de Chomon had a single trick: stop the camera, move something, start it again…Over the course of a hundred years, the house of wise-cracking, self-aware objects grows less funny and more unsettled. Ghosts skip beats and travel in bursts, finding horror in the familiar, language in motion.”

One hundred years later as Robinson revisits these films, fear of death remains, but Robinson highlights a very different death.

“Imagine Death distracted, lost in nostalgia, watching Netflix, or momentarily dazzled as the hidden spirit of beauty breaks her blossoms all about his chamber.”

By evoking Death awash in the immortality of film images (they are immortal as commodities), Robinson expresses his central criticism: Like the New Sincerity, or any contemporary poetry worth its salt, Robinson rejects the precious simulacra of nostalgia, underlining the inherently timeless aspect of all media commodities today. Critics refer to this as a loss of historicity. So when Robinson revisits these films, it isn’t nostalgia he’s interested in, but reinterpretation. For him, timelessness is the specter of death/undeath on the celluloid, the inevitable homogenization and incorporation of human endeavors into the service of a repressive status quo. By calling out this timelessness, and reinterpreting the art, he stages a sort of intervention. And he restores some of the vibrancy of these images that, “broke free, first from stillness, and then from their creators.” In the face of eternity, Robinson begs a brief interruption for fresh air.

When I was sixteen, McDonald’s did not call me back, even to say no. The sweaty-browed manager instinctively knew I was not McDonald’s material…Burger King took me in with the grace of a neglected mom, and put me beside Glen, who had stolen a lawnmower not once but thrice and now had a lopsided back tattoo of a skull…For joy, Mr. Sarcastic in the Drive Thru, I messed with your food. The last laugh is mine.

You are not your job, there are no dividing lines in the soul. For whatever I am, I am also Burger King and Di Nappoli Pizza, Ponderosa Steak House and grocery stores and bookstores and café sinks filled with dishes. I am a human sign for companies with inexcusable indifference to human suffering.

In a great essay published by those geniuses at Sentence Magazine (#3), Maxine Chernoff meditates on the essential politics of poetry, and especially prose poetry, “As a young writer, I remember reading Christian Morgenstern, whose Palmstrom was like me, noticing absurdities everywhere, relishing them with the intensity of a dog finding a fine red fireplug. I discovered Max Jacob, Blaise Cendrars, the “travel journal” of Osip Mandelstam…The prose poem was a tone poem, the tone often the same because the prose poem of the 1970s was the chosen vehicle for both amazement and disillusionment with the world.” Robinson shows this same mix of amazement and disillusionment, and his poetry explodes magical, lyrical, and urgent.

***

Joseph Houlihan lives and works in Minneapolis, MN.

Tags: All Movies Love the Moon, Gregory Robinson