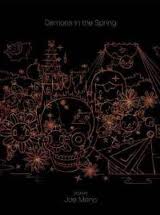

When I was charged with the task of contributing to this superneat project hyping Akashic Books’ redux of Joe Meno’s short fiction collection, Demons In the Spring, I felt entitled. For years I’d been a pestering cheerleader for Meno’s novels, The Great Perhaps and The Boy Detective Fails. Although the former got a fat, excellent review in the Times, I still felt Meno was somehow criminally under-heralded, a vital voice in need of a louder advocate. So when I got the chance to be that advocate, to ruminate on one of the collection’s stories, “Get Well, Seymour!”—a sad, excellent tale about cruise ships, inevitability, and psychosomatic parrots—here’s what I did:

When I was charged with the task of contributing to this superneat project hyping Akashic Books’ redux of Joe Meno’s short fiction collection, Demons In the Spring, I felt entitled. For years I’d been a pestering cheerleader for Meno’s novels, The Great Perhaps and The Boy Detective Fails. Although the former got a fat, excellent review in the Times, I still felt Meno was somehow criminally under-heralded, a vital voice in need of a louder advocate. So when I got the chance to be that advocate, to ruminate on one of the collection’s stories, “Get Well, Seymour!”—a sad, excellent tale about cruise ships, inevitability, and psychosomatic parrots—here’s what I did:

I sat on the assignment for five months.

Similar to when I discovered Soul Coughing in high school, or watched Chris Smith’s American Movie in college, or saw Donald Antrim read in grad school, I felt from the moment I read Meno’s fiction that it pulled off the rare coup of capturing in full, vivid form the kind of voice and spirit that drew me to want to write in the first place. Which is to say, the voice and spirit I wished, desperately, was my own. His manner was playful but heartfelt, inventive but tough-shouldered; yearning, swift and relentless. He used drawings. He included, on the back flap of Boy Detective—a dark, YA spoof that shoved an Encyclopedia Brown-like boy genius into a far less genius adulthood—an actual secret decoder ring. Meno wrote with tender wit about the lonely burdens of an over-ripened intellect, the frightening promise of adolescence, and its cruel ability to solder itself onto adulthood in hilarious, disorienting ways.

So why then, couldn’t I get it together to give the man’s work a proper appreciation? I knew when I read it that “Get Well, Seymour!” was a slick, potent distillation of what I’d read in Meno’s novels. The narrator is a dejected Princeton sophomore left by his parents on a luxury cruise ship to watch after Alexandria, his awkward, hypersmart tween sister whose “features seem both mismatched and regrettable.” The pair soon find themselves under the thumb of a third party: Sabine, a sly, commanding teen girl with equal capacity to bewitch and destroy. What happens after twists each character’s perceptions of one another in the ways good fiction does. Sabine may or may not have leveled a crushing insult at Alexandria, which sends our alienated narrator out to confront Sabine’s cruelty. What he encounters, though, is a cursed opportunity to betray the sullen parts of himself that bond him so strongly to his sister, and instead experiment with a hopefulness he neither anticipated nor knows what to do with.

I loved it. But what I loved about the story was different than what I loved in Meno’s novels. Rather than trigger me to grab someone and say Dear lord, read this, “Get Well, Seymour!” made me fiercely proprietary. I wanted it all to myself, probably because for the first time, Joe Meno’s work was no longer speaking for me. It was speaking to me.

I’m mostly an essayist and memoirist, and as a reader I’m pulled to those genres for the ways in which they position me as a secret witness, a voyeur to another’s deeply reflective moments. I enjoy the addictive viscera of being a spectator. Yet I’ve always been in terrible awe of the short story’s ability to present but not solve; to walk a reader to the precipice of reflection then abandon them there to discover introspection on their own. Sometimes that work is harder than reading essay or memoir, and sometimes its more rewarding, but almost always more personal. When it came to “Get Well, Seymour!” here’s the exact passage where I knew I was a goner:

“I wish I was in college already,” Alexandria says. “I wish I could study whatever I wanted and not have to worry about whether people liked me.”

“It will happen soon. Someday you will find yourself surrounded by people with the exact same interests as you, and you will never feel out of place again,” I say, already weary of the lie I am telling.

Since I’ve been both young, smart and pissed on, as well as older, dumb and callous, I became at once the narrator and his doomed little sister (and even somehow the troubling Sabine). The story’s greatest gift was leaving me with the task of figuring out how.

Look: it took a while. Five months, in this particular instance. I’d walk away from the story and come back to it weeks later, only to find that my relationship with the thing had complicated more, that the conversation had deepened, the parts of me it exposed had matured. Almost half a year later, “Get Well, Seymour!” is still speaking to me, and I still like listening to it.

So my appreciation of the Joe Meno’s story, I’m afraid, comes late and with apologies. Because I know that appreciation is half-baked at best; that in a few weeks I’ll come back to the story again, waiting to hear what else it will tell me. But I’m also betting that was Meno’s goal all along.

Tags: demons in the spring, joe meno

holla hairstyles of the damned & tender as hellfire — haven’t read the shorts…

I’m actually reading this collection now. Thanks for this.

Man I loved soul coughing in high school.

ta.gg/4vh