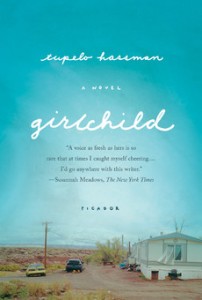

Girlchild

Girlchild

by Tupelo Hassman

Picador, Feb 2013

288 pages / $15 Buy from Amazon

Rory Dawn, the screaming sunrise, is third generation in a line of women who grew up too soon, and grew up to grinding poverty. She lives with her mother in a trailer park outside of Reno called the Calle. The Calle is a dumping ground for all the usual white trash suspects: drinking and gambling and smoking and teen pregnancy. There is also plenty of literal garbage (popsicle sticks, beer cans, homework assignments) swirling around in the Nevada dust. The kind of place where people regularly have to choose between paying the water bill to keep the toilet running, or buying a tank of propane to keep the heat going.

Rory’s mother, Jo, tends bar when she’s not sidled up to one. She lost her teeth young, and Rory’s greatest joy in life is seeing her smile wide, without her hand hiding her dentures. Rory’s grandmother lives in the trailer down the way, and spends her time gambling, knitting, and trying to make things grow in the harsh dirt. Both women want nothing more than for Rory Dawn than to grow up and “get out,” without making the mistakes they did. Neither has the first idea how to help her achieve this goal.

Growing up is a dangerous journey for Rory. At school, she performs off the charts on standardized tests, and scrawls “I hate Rory Dawn” on the bathroom wall. On the Calle, predators like the Hardware Man won’t even wait until a girl like Rory starts to fill out.

Girlchild works hard to rid us of any notion that the point of the story is whether or not Rory will “get out.” Calle life is a circle, and it’s impossible to draw the line where the past meets the future. They call poverty a vicious cycle, after all. To this end, Girlchild is told in a disjointed, highly metaphorical narrative, jumping around among all the most mundane and most heartbreaking moments of Rory’s childhood. Much of the story is in 1-3 page mixed genre vignettes, many of them sad and clever, like the word problems that make no sense and have no real answers.

A man with 9 fingers has 4 times as many male grandchildren as female, and 3 times as much regret. The amount of regret is equal to the number of times his shoulder has been dislocated from the recoil of a shotgun blast at 21 foot-pounds of force per bullet multiplied by the number of times he has been called a dirtbag to his face. Given the number of shell casings littering the bedroom floor and the number of shells ready in the box, how many of his original 4 daughters have been deafened by gunshot? (Show all your work)

A) The jar holds 5 times as many pennies as nickels

B) Each team will need to load 12 bags of dirt

C) The mother will purchase 22.4 yards of gingham fabric

D) The shotgun blast echoes for at least 3 generations

[188]

Others are tedious: one wonders what value three sets of blacked out pages offers that one would not. Rory fills in the backstory of her mother’s life with reports from social worker V. White, and letters from her Grandmother (who eventually moves off the Calle and back to her native California). But the V. White sections are downright expository compared to Rory’s touching, inventive ones.

Overall the mixed genre vignettes do escalate GirlChild’s literary merits, especially the ones that take their forms from the Girl Scout Handbook Rory treasures as her most prized possession. “How to:” Rory tells us, for a series of impossible tasks. How to be a Girl Scout without a troop. How to ignore what the Hardware Man is doing to his daughter on the other side of the bed. How to mix an American Dream cocktail (“Equal parts sweat and heedless disregard, dash of bitters, lucky twist” [177]). Her voice is unlike any other. Her descriptions and turns of phrase are like a smoking gun, loaded as they are with such heartbreaking meaning.

She doesn’t speak to us in terms of socioeconomics or character flaws, or any of those usual suspects when it comes to poverty. Such things are inadequate to truly understanding the Calle. Rory is acutely aware of her place in this world, far beyond her years.

Girlchild is not about what poverty is, it’s about what it means. This is not a straightforward question, and Tupelo Hassman gives us no straightforward answers. The best we can do is admire the bittersweet beauty of it all.

***

Claire Blechman is from one frozen hinterland or another. She is an honorable-mention-winning writer, thanks in part to her MFA from Emerson College. Her work has appeared in The Fiction Desk, Gargoyle, Interrobang, the Ploughshares review blog, and the Vault Guide to the Top 100 Law Firms. She wrote her whole website by herself, then unimaginatively named it claireblechman.com.

Tags: Claire Blechman, Girlchild, Tupelo Hassman

tinyurl.com/lr69xbu