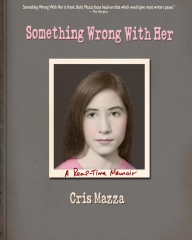

Something Wrong With Her

Something Wrong With Her

by Cris Mazza

Jaded Ibis Press, 2014

388 pages / $18 Buy from Jaded Ibis or Amazon

This amazing “real time” memoir by Cris Mazza deserves a love-letter, and also a review or maybe six, written at different points while the reviewer is reading. Some would be awed and respectful, some would be infuriated, or in tears. I was obsessed, and ended up forming intense bonds to the characters, the love story, and the way of telling. It’s such a complex book, it’s taken me months to try to write about it, and even now….

The basic format is that Mazza sets out to explore what she characterizes as her sexual dysfunction, which she intends to both confess and try to explain (to herself and to us), through an examination of her sexual and emotional history. But as she’s working on the book, she gets back in touch with a high school boyfriend, and the story she thinks she remembers starts to change. She begins to include the story of their current emailing, along with old journal entries, earlier draft versions of the same chapters, and excerpts from her previous published books, which have fictional versions of real events, remembered and re-created at different points in time.

A strange note: The book was supposed to come out in fall 2013, and a cover was released and some advance reviews came in, but due to problems with the publisher, it was finally published with a different cover in April 2014.

Most of the other writing on the book has addressed its feminism and sexual politics—Mazza is a well-respected writer of experimental literary fiction with 17 books to her name, known for graphic sexual content and a feminist bent. A previous novel was titled Is it Sexual Harassment Yet? She edited a collection of “chick lit” before that was a term that meant a pink-shoe. And yet in this book she confesses that she has or had vaginismus (a spasming condition that makes penis-in-vagina sex painful) and has never had an orgasm. She also admits to many un-modern-feminist thoughts, like considering herself to be frigid, and thinking her body is dirty.

Her honesty is brave, rare, and hopefully might be helpful to other women who suffer from the same problems. Mazza found talk-therapy to be useless and something called Pelvic Floor Therapy helpful in decreasing the pain during sex. It’s refreshing to hear a woman—especially an older woman—speak honestly about sex, especially when she’s admitting to the uncoolness of not liking it. As she points out, we usually hear from women who are having too much sex, and though this is presented as a flaw, “isn’t the unspoken aura that these women are—for the same reasons—exotic, worldly, exciting, charismatic, provocative…or just plain cool?”

But for all its frankness and willingness to tell-all, Something Wrong With Her isn’t self-help book or a statement of sexual politics. The quest as Mazza writes it is not medical or feminist-political, or even psychological, but historical. She wants to know what’s wrong with her (in her own words) and embarks on “a memory-search for the reasons my sex life had been set on a path towards dysfunction or complete failure….” She looks at her early sexual experiences, her feelings about her body, and most of all, a handful of relationships where she felt violated or controlled by men. Early boyfriends pressured her or were rough. She was a band geek in college, and worked in the office for a band leader who she had a hero-worship crush on, which she feels was obscurely damaging. A later boss was sexually inappropriate. All of this is explored on an infinite loop of repetition and re-visiting, in obsessive detail.

Were these events damaging, or just normal? Mazza, looking back, concludes that no real crimes were committed and that her problems are no one’s fault (but her own). I recognized many of the events as “normal” occurrences from my own adolescence, from the creepy and insinuating boss to the unpleasantly groping dates; for me, these were sexual wrong-things that happened along the way to discovering sexual right-things. For Mazza, they were something more. At one point she writes, “Mark, why don’t I ‘stand things’? Why have I never? Why am I not ‘over’ anything that’s ever happened or not happened?”

Perhaps that’s the right question, but it made me wish for a wider cultural interrogation. Nothing “bad” really happened to her, but on many levels the whole stew is bad. Our culture’s focus on “sex” as the act of heterosexual penetration is ridiculous. There is no one sex act that fits everyone; there is no correct assemblage of parts. Mazza’s sexuality bears this out, but she can’t say “I don’t like that; I want this instead,” so she considers that she’s a failure at sex. She also writes about her sense of failure at being a desirable woman, since she’s uncomfortable with femininity and dislikes her female parts. (At one point Mark asks her, “When did you start thinking of your body, there, as a wound?”) Is she a failure as a woman, or do we as a culture have an idea of “woman” that doesn’t fit everyone? If your assigned gender role makes little sense to you, maybe it’s more difficult to roll with the usual small violations and humiliations of adolescence. Mazza is in her late 50s, and the feminist theory she quotes is second-wave Erica Jong, but I’d imagine there are young women like her today, still feeling like failures because they don’t live up to “sex” and “woman” as commonly described.

Increasingly, the book turns into the love story between Cris and Mark. The reveals on this story are so brilliant (one happens, unbelievably, in a footnote, about halfway through) that I don’t want to say anything more about the plot here. Except maybe, Oh Cris, Oh Mark, Oh Cris, Oh Mark. You are killing me. We’re all waiting to see if Mark can cure her. We all want to know if it ever turns out like the fairy-tale.

(My contribution to posterity here, in case I happen to be reaching any masturbation-shy, non-orgasmic women in my humble blog post, consists of two words: bathtub faucet. You will need to find one with decent water pressure. Try it. Please.)

I had long wondered if the quality of an Internet affair (Mark is married when then story starts) could be recreated in a book, if the tension of the correspondence could be made narrative. Mazza has done it, which is funny since she’s a pre-Internet age writer often using handwritten diary entries from a time long before e-mail. Yet those diary entries capture something quintessential about how people connect online, when we so often turn other people into our diaries, when the relationship is as much an exploration of self as it is of the other. The whole book is a diary, and a correspondence, and it played for me nearly as effectively as I were part of the affair, in real time.

Some of the most poignant and beautiful lines in the book concerned that morphing between writing and life. “Basically: while I wrote this book something happened. Something happened while I was writing the book I thought I was going to write, which turned it into another book altogether.” Or, “Oh Mark, what am I going to do when I finish this book? It’s the only life I’m living. How does a person who only lives when she writes, write a memoir?”

The aura of dreamy, self-absorbed storytelling that many of us recognize from obsessive e-mail correspondence pervades the book. Mazza jokes in several places that she’s going into way too much detail. “Why include this barely significant vignette of a heartbreak?” she says at one point. And in another she mentions something that (I’m paraphrasing) “no one would care about—but Mark I know you do.” I loved her for it, and Mark too, for caring, but I would be remiss if I didn’t note that there were times I couldn’t believe what I was reading—and couldn’t believe I was still reading it—like, the time the school band went on a trip and Cris’s boss, who she had a crush on, “betrayed” her by not riding on the bus, and not calling to make sure everyone was OK after the bus broke down. Sometimes I just had to laugh. The humor was deepened by Mazza’s inclusion of comments from her writing group, who rightly point out the many reader expectations that she seems bent on frustrating. Go, writing group! One particularly funny part was someone telling her that having a crush on a high school band teacher was itself humorous. (She was indignant, and didn’t agree.)

I thought she got away with it all, partially through sheer commitment and partially because she’s a great writer with an excellent grip of pacing and suspense. Anyone wanting to write a deconstructed memoir, or include e-mail and text in a book should use this as a guide. As testament to her prose abilities, here’s a snippet from her fiction, from a story quoted in the book called “Let’s Play Doctor,” that seems representative of her lucid, risky, bold approach:

“She has a magazine in her hands and Dr. Shea moves behind her, very close, his cheek against hers. The smells from the bakery at the back of the bookstore become potent. She sees a whole pan of buttery cinnamon rolls coming from the oven. She doesn’t let go of the magazine; she can feel the slick heavy pages in her hands. Dr. Shea kisses her neck. ‘Let’s check your wounds,’ he murmurs. She’s looking at the magazine but doesn’t see anything. Dr. Shea lifts her shirt and runs his finger along the line where he had cut her open.”

I’ve written all this and not mentioned the explosive political content. Is it rape if we change our minds about it later? Can we call teenage grappling “rape games”? Do we dare admit to eroticizing our traumas? Is it sexual harassment if we want it? Mazza’s experiences with authority figures, and the men in her life, raise all of those questions in ways that aren’t always comfortable. She admits to calling situations that were or turned out to be ambiguous “sexual harassment” and “sexual excessive force.” I don’t like a world where ambiguous shit like that is legislated, and at the same time I think it right and necessary that sexual harassment and rape are illegal. It’s a mess, and this book does not help clear it up (not that it’s supposed to).

What it does—wonderfully, agonizingly—is look at one woman and her experiences with sex, in a deeper, more real, more fascinating, more exposed, more sexual way than I can recall having read anywhere, and all that in the middle of a firebomb of an Internet affair. What you want in a sex memoirist, it turns out, is not a blogger with a cute Instagram, but a hard-core old lady who has written 17 well-regarded literary books and never had an orgasm. I am only pretending to be surprised by that. I am not surprised. And I love you, Cris Mazza.

***

Valerie Stivers is a freelance writer, who blogs about her reading list at An Anthology of Clouds.

Tags: Cris Mazza, jaded ibis press, Something Wrong With Her

Great review of a terrific writer’s book.

[…] (The following review is cross-posted today on HTML Giant) […]

[…] actually had to go back to my past to find him. He was back there waiting for me. That’s a longer story. I’m not sure I would trade it in, now, for a complete and normal sex life. But that shouldn’t […]