I.

I.

Beginning

There is a small world nestled in a big sky. The small world has its own sky, land, people, animals, etc. etc., and although the world is small, if you take the world’s train, you begin to see that the world is vast, because the train travels a meandering route in a hypnotic motion.

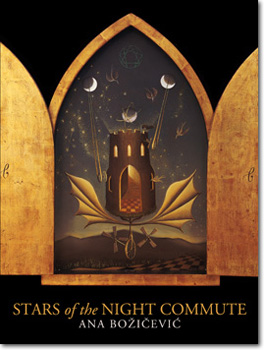

We get on this world’s train when we read Ana Božičević’s book, Stars of the Night Commute. The passengers are intimates, yet they are covered with a film of remoteness, and the commute at times bores through this remoteness, and at other times travels the periphery. The abiding mystery of this commute is presented through lines in an early poem, “Always the beast has a remote heart.” And then at the end of the same poem, “At the end of poetry the poem can no longer be remote.” This tension between remoteness of the beast’s heart and intimacy of the poem’s heart causes the whole of the book to ache in the way of a taut muscle stretching to span these disparate realms.

How do we get from point A to B when we are involved in the physics of a dream? Is there a point A and point B in the physics of a dream? In the Stars of the Night Commute, there is a starting point, where the window is opened and air flows in. And, at the end of the book, is the closed and summerless room. But, the route between the two also climbs and descends, skips and glides, as we are woven through memory’s scaffolding. And, on this same variegated route, we are led round and round the circular path, an endless mulling that causes a thought to be worn down to a “white pebble.”

The power of the book is that it captures you on the train, seating you by a window through which a stream of images lulls you to a drowsing that projects on your mind’s eye the strange acuity of a dream. Sometimes the train travels in the sky itself and you find a bit of peace in the expanse, but you can’t escape the haunted route, the ghosts of another’s memories arranging themselves into complex compositions somewhere nearby. It is a train that holds the passengers’ pasts so vividly that you are led to enact their memories in real-time. And then a part of you begins to believe it’s your past waiting at the next station.

(Sometimes my dreams will ache the way these poems ache. One of my intimates is covered by a film of strangeness and infused with an obscure breath. I try to connect with them as I would in my waking life, but I can see tiny tears in their corporeal familiarity, and I know that if I were to rip away the facade, I would find, within their inner chamber, the night sky floating its rootless stars.)

The ache is the axis around which the constellations of these poems revolve (stars as the ancient navigators; they place us and diminish us at the same time as they spin their carousel of stories). Here again the remoteness and the intimacy share an improbable space: the distance of stars, the axis that quarters the heart.

The ache in The Stars of the Night Commute is the journey of the poet commuting through an existence that can’t quite give her the substance with which to commiserate, so that her pain and grief become resigned to her internal voice, which searches out plaintively, over ever-shifting landscapes, for an absorbent surface.

II, III, IV

Immersion

(The non-italicized passages are poems and parts of poems from Stars of the Night Commute. The italicized parts are my responses to the passages.)

He showed me this book called “Discovering God.” And guys?

I nearly did choke on the swanning spray of insufferable light—

“Some people can only take seconds

of God’s voice,” he said. But for me

it was, like, the rubbery-awake I get after a slap,

or (not that I did that in a while) after I

write a poem, then open the window

to the naval dawn air.

I see a hawk being chased by sparrows.

And I won’t ever again write simply again

“cause I won’t ever feel

the simplicity of an again bloodthirsty

sparrows.

The air is filled with anomalies. You can catch the anomalies in a net, but as soon as they’re snared, they grow large jaws and haunches and are easily able to tear the mesh and bound, unstoppable, to their kingdoms.

Always the beast has a remote heart.

“Cross seven seas, beyond two hills as two

Lambs facing each other, in a meadow fine as my lady’s kerchief, a boar

Grazes:

Inside the boar’s a hound.

Inside the hound a rabbit.

Inside the rabbit a grey dove.

Inside the dove

At the end of poetry the poem can no longer be remote

(Each desire’s minutia: so complex that the archetypes chisel themselves out of each other, freeing their pent-up limbs.)

I pick up the flesh figurine that has emerged from the plastic beast and am amazed by its warm hands, a sign of good circulation.

And I pull the hand to the apex of my lens because it is the fingertip whorls I want to enter as a stone enters a pond.

And wouldn’t it be cool if Bloomberg was Prez?

Or wait, I know: Trump! (It would be

awesome. Now spit out those feathers—)

Rid your mouth of the sorrowing of sparrows

We cut into the contemporary and find veins that flow with crude oil, but along comes “sorrowing of sparrows” to show us how to cry our eyes out and onto

the socketed terrain.

Is the poet free from tyranny or complicit as she bears each

word

the body-source of each rivulet.

Because you can’t touch cloud.

What you want to say is cloud.

Peak light on the mountain

at high noon it is easy to forget the abilities of night’s

apex

like how it can lend

a blind ear

to a disarray of pleas.

Out of the body of a dead dachshund A mountain of luxury. Asleep in its branches was luxury, badgers born blind into luxury—their crying was luxury, above all luxuries. But love was usury. It counted the pennies of the person, chanted Dog in the yard where there was no dog.

something lost inside us

the Dog

fights for the smallest

gulp of air

uneven breathing

righting itself, barking hollowed-out

to howl.

So sorry, dear star that came before the night

Sunset,

why are you so often forgotten? Why are we startled to move our eyes from screens

to windows to find

that, unbeknownst,

all has turned night?

first

Sadness plus finance equals luxury. Commerce plus treetops is travel. What then of the mountain? Once upon a time in a far off land, there lived a kind Louis Vuitton the Third. For a summer job he worked at the Dairy Barn on Broadway, and there, quite by accident, he fell in love.

later

Something was off. King looked and saw dachshund had ossified, and then walked around the still body, it was just a front, with a stick from behind. Where was Dog? King tore his stole in sadness and started walking.

later still

The clouds raced together to form a pretzel. It pointed to something dirty. The joke was something to laugh about – almost nothing, but he knew he made contact – like two flavors perfect together, the indoor palace everyone talked about Each little thing a luxury good Or the star he had read of, that shines in the sunset: a root. His status as leaf.

King without Dog—a familiar scenario

Atop the mountain with a cloud on either side of his leaf

(remember, this flat mouth was once a root)

King looks out at sunset and absorbs.

III.

I’m on a train with passengers

that all hold a menagerie behind

their plastic skin (plastic because this is the substance

given us

to mold the modern).

passenger1, your menagerie is by far the largest. And inside your menagerie is the Zoo, with the animals that say, “Why have we been trapped behind these translucent bars that surround us like a breeze?”

If the world’s time is God, and she’s birds

atwitter, then why must I go to work?

The answer writes itself:

left to my own devices I’d just sink into the soil.

That is, write, with dirt

as my pillow.

Sit under the mud-sky for long enough with the month’s stratum liquefying and pouring out from between your legs…

Show me the bouquet!

If you do, I won’t tell on you

to the rose of the world. She can make him hear you up there.

Besides, it’s not a cliff, it’s a chair.

And the rose is God.

Got it?

Gott it?

That is why women should be president.

When you pull a thorned bouquet from your mouth, is it the opposite of how the men eat fire?

The bleeding almost staunched…

face the rabbit that comes at the end

of autumn, meaning “nothing,” &disappears

among the leaves—

fertility of “nothing” :

The poet writes in pure snow with pure snow as ink The poet becomes frost bitten and frost gnawed, and then when the poet writes “frost” in the snow with snow-ink, we feel numbness set into our arms. We feel that frost multiplies like rabbits within our pores.

White

out

Rabbit-husband

are you scared

of this thing behind the wallpaper? It’s

silence

silence stored behind wallpaper

you

behind wallpaper affixed

with a thin skin.

Dearly beloved, we are re-gathered here today to carefully remove wallpaper from the castle, to free man and wife from utter silence, to bestow upon them rabbits and shadows.

The soul was painted over and over, like an outlet.

The Soul: its interchangeability makes it the perfect garment. Let’s gather the chairs around the soul and eat slugs.

passenger 2, open your shirt like a venetian blind so that we can see through your window to the interior weather.

It’s raining &

little-ones-of-rain

are talking to him.

“Color is torment.” Or:

“Fool, your book is getting wet.”—

cackling like peppercorns

from the bright green. (I

get now what he said about brick:

it’s relentless, eaten

by history. Eye-blue acidity

aging

all it’s touched.) O bomb

of the world seen and unseen!

If he told them to shut up,

the talking would cease.

But he’s in the room without decisions.

Stand below the leaves of ivy holding baubles of rain that you can touch and watch shake in their skin.

careful not to release them

that name’s an

empty

water bottle. Someday its sound

will be emblem

of my temperance. But now?

it’s sorrow.

passenger 3, we are constantly left wondering, who have our accidents maimed?

What poem will come from the wound?

my mind is simple, I’m just feeling these days, crying over my old dog

my mind’s just simple, it’s feeling my days, a dog crying out. These old

tablecloths

(Have you ever tried the trick where you yank something out from under something else and the something once on top merely wobbles in the wake of the absence of the thing that was yanked?)

But you needed something to shatter

Amy, Amy, at this distance you’re

the smell of liver,

tinnitus that keeps me up, afraid:

your fortressness must now be tested.

The way you took me in without

a surfeit click or

gesture: seagull kerchief

binding my gut to safety

on the swimming haul

among night-images. I went to the place I was born

and it plainly was a bride. So I ran after her.

When she turned into a star I swallowed her.

And out of this uneasiness will come

an aster.

These are the ways to speak: tightly woven around an object, trailing a verb like wake, the tongue-language of bitch-ass, through a mini-book opened to seagull written with seagull ink.

Passengers 4 &5, I see that your plastic undershirt protects you, but the empty leash hangs from your heart…

Carried you this far. Dachshund in the snow. Lights

wink, now— I can’t take another step— Why

push against me with your little red foot, so? For

tens and tens of blocks, & belly-up, and wheezing

later

we’re at the gate. Say, Mother! This is John I carry. A thing

drilled him invisibly—and now he make a hollow sound, a little like

a bathtub. Is it alright to bring him in? He’s heavy, and I—Oh. I see.

No. What, leave him here

for nuns to find? Walk back? (O I won’t make

it back)—we’d passed some hundred

restaurants—I have no money—and it rains—

You are gathering sleet that someone said was rain,

keeps insisting, “it’s rain”

but we hold our black gloves out and they are spotted with constellations.

You are taking wheezing dogs to gates and we are still married to them, still sporting the matching rings, although one is thinner, like a reed.

Walk hand-in-hand with your dog for so far and then, suddenly, your dog is gone and your empty hand is a paddle against the air, turning you in circles.

(When I had one thought

for months at a time. When I wore it

to white pebble.

Like a young horse

of a single color—)

IV.

Now, all of us sit with our tableaus arranged behind our wispy breastbones

and we are slowly drawn forward

Swept many thin things are

sideways in blue and pink

with whose broom, the evening sky

grand not speaking not a question

The rose thorn punctures the throat

she says, war, and plugs the small hole with tar

swallow a rose bouquet and then

swallow a war. What color

blooms inside?

And look: roses wait, the widowers.

Their brief terms are Nordic, a violin concerto.

Each is a number: an ardor in order.

Like them he is measured against pearly histories.

Releases that rudder. A little bit lower—

(You’ve almost forgotten–): There, we’ve both signed it.

He plays at being a thorn.

endurance is felt as the thorn inches deeper. What has been withstood, stood within the hour of emptied-out asters.

(the poem knows its limits, that is the Thing of the poem.)

On the shore of blue/pink sauntering in: We’ll find small, bleeding objects nestled in the sand, We’ll say, “My beloved, from which war did you arrive over waves?”

(The memory of a book of plastic cadavers and their innards, lovingly crafted and rested on black felt. An exquisite room, many chambered, dark red, blue/black, dappled by light through skin, latticed by light through ribs)

The caption: The heart laid open.

the sea and the sky and the stars, yet I keep collapsing inward.

(In our garden the vagrant would sleep

like this, under a low tree

in the center of a circle of cobbles.

I was turning circles like a weather vane. You nudged me from sleep and said, “Check your pockets to see if you are that vagrant…”

I’m almost crying, sewing, barking: almost slowing

down. What’s slain? Your name: a large curvy

European key. The hall door opens. Hall smells

of an old lion’s thoughts in a Zoo. You enter, close

opened windows. Your room’s summerless.

V.

End

“Always the beast has a remote heart.”

These poems equip us with all kinds of eye-pieces, micro to macro to mercurial.

They help us remember the kind of hearing that no one has been able to draw in anatomy books.

They open a nose that parts the stale ocean with fragrance and incise a tear duct within our third eye.

These poems inflate from our hearts like airbags that keep going out, past our collision and into the atmosphere.

They wear our hearts down to a small stone that we can skip across the sea.

They put us on a train that takes us to cold mountains, to hell’s orchard of chairs, to the gate, to blue washes over stars, to the master trailing the Dog-star, to the sunset before stars, to the stale and summerless room…and when we look out the window, we see, at the edge of the outermost regions of our sight, enveloping the whole commute, the dense inner petals of the rose.

“At the end of poetry the poem is no longer remote”

***

Kim Parko lives in Santa Fe, NM with her husband and dog. She is the author of Cure All (Caketrain Press, 2010)

Tags: ana bozicevic, kim parko, stars of the night commute, tarpaulin sky press

“At the end of poetry the poem is no longer remote”

We never arrive intellectually. But emotionally we arrive constantly […]. –Wallace Stevens

[…] Stars of the Night Commute by Ana Božičević | HTMLGIANT. […]

Kim, thank you for this response, it awes me! You rock.

Love, Ana B

Hi. how doi I get a copy? Sue Amy’x mum