Tall, Slim & Erect: Portraits of the Presidents

Tall, Slim & Erect: Portraits of the Presidents

by Alex Forman

Les Figues Press, 2012

131 pages / $15 Buy from Les Figues Press

James Monroe was the third president to die on the fourth of July. Franklin Pierce was arrested for running a woman over with his horse. James Buchanan carried his head cocked to the side like a poll parrot (whatever that is). These and other trivial-pursuit answers are drawn from Tall, Slim & Erect: Portraits of the Presidents, Alex Forman’s compelling and often very funny book of short presidential biographies. With text appropriated from dozens of sources, Forman presents us with a surprisingly dishy view of our first thirty-seven leaders that, through her light touch, still manages to bring up some highly relevant questions about our expectations of history and our chaotic construction of public figures.

In his introduction to the text, Ben Ehrenreich characterized Forman’s effort as one to humanize the presidents, and the portraits are, indeed, deeply human, with a heavy emphasis on personal foibles and physical oddities. The Presidential body is essential to these portraits. Of course we might claim that the presidential body is essential to a great deal of political discourse—from Obama’s smoking and Cheney’s beat-less heart to that final dictatorial accessory, the glass coffin—but what Forman gives us is something different, not the body as symbol or the body as tool of power, but the body as body. Grant “had unusually small hands and feet,” Coolidge was “deficient in red corpuscles,” and while Washington’s famed wooden teeth don’t make an appearance, his pockmarks and bouts of dysentery do. The bodies depicted here are intimate bodies, embarrassingly physical, and not fit for public perusal—which makes it especially striking that this book is, in large part, a compilation of public perusals. Drawn from a few centuries worth of news, diaries, histories, speculations, Wikipedia articles, and gossip, Tall, Slim, & Erect is a distillation of the public gaze.

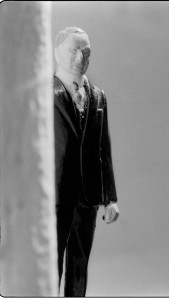

Making this formulation of presidential physicality all the more beguiling is the way the text is paired with images. Each textual portrait is accompanied by a photographic one of the Louis Marx presidential playset—a set of figurines the famous toymaker began marketing in the mid-1950’s. Each presidential body, so fully explicated and worked-over in the text, is reduced to a sixty millimeter plastic figure. The likenesses are fairly good, but there is a kind of necessary uniformity. Madison (our shortest president) stands sixty millimeters, as do Lyndon B. Johnson and Lincoln (our tallest). Taft, with his famous, bathtub-sticking rotundity appears only a bit thicker than anorexic FDR (who is shown standing, despite his polio). The faces are different, but the bodies are the same. In effect, these presidents have no bodies, the pictures remind us, at least none that we can see through the haze of time and expectations. The president as person means something different and perhaps something less than the president as figure, and the attempt here to humanize is less interesting for its success or failure than as a catalogue of what it might mean to humanize a public figure. A president is, after all, a human, but one who has been so denatured by his role that we must embark upon these kinds of recuperative missions to see him as such. Do we become more human in one another’s eyes through the workings of our bowels or the oddities of our forms? Perhaps these are the very things we need to strip from our leaders in order for them to lead, fearful that too much body will leave them mired in the petty and personal. Or perhaps in confronting the truthlessness of history, these are simply the easiest elements to give back to our presidential figurines. Knowing about Truman’s bad eyes stands in for knowing what it means to be the man who dropped the bomb. Unable to comprehend the Cuban missile crisis, we muck around in the brain and bone of Kennedy’s head. Perhaps in our search for presidential humanity, we are just naïve phrenologists, asking the body for answers it does not have.

Making this formulation of presidential physicality all the more beguiling is the way the text is paired with images. Each textual portrait is accompanied by a photographic one of the Louis Marx presidential playset—a set of figurines the famous toymaker began marketing in the mid-1950’s. Each presidential body, so fully explicated and worked-over in the text, is reduced to a sixty millimeter plastic figure. The likenesses are fairly good, but there is a kind of necessary uniformity. Madison (our shortest president) stands sixty millimeters, as do Lyndon B. Johnson and Lincoln (our tallest). Taft, with his famous, bathtub-sticking rotundity appears only a bit thicker than anorexic FDR (who is shown standing, despite his polio). The faces are different, but the bodies are the same. In effect, these presidents have no bodies, the pictures remind us, at least none that we can see through the haze of time and expectations. The president as person means something different and perhaps something less than the president as figure, and the attempt here to humanize is less interesting for its success or failure than as a catalogue of what it might mean to humanize a public figure. A president is, after all, a human, but one who has been so denatured by his role that we must embark upon these kinds of recuperative missions to see him as such. Do we become more human in one another’s eyes through the workings of our bowels or the oddities of our forms? Perhaps these are the very things we need to strip from our leaders in order for them to lead, fearful that too much body will leave them mired in the petty and personal. Or perhaps in confronting the truthlessness of history, these are simply the easiest elements to give back to our presidential figurines. Knowing about Truman’s bad eyes stands in for knowing what it means to be the man who dropped the bomb. Unable to comprehend the Cuban missile crisis, we muck around in the brain and bone of Kennedy’s head. Perhaps in our search for presidential humanity, we are just naïve phrenologists, asking the body for answers it does not have.

Ultimately, all these attempts to get a glimpse of the presidents as they were, as men, only serve to highlight the impossibility of sorting out truth from speculation. Forman’s selection process, wide-ranging as it is, cleverly sates us with a glut of information while withholding any means by which to judge its veracity or, more importantly, its meaning. There is a nine-page bibliography, but no attributions within the collaged text, so we cannot say whether any given tidbit is from The American Heritage Book of Presidents or from snopes.com. We begin to wonder if it matters. This is the biographer’s dilemma writ large; in the end it is not the words that are bafflingly contradictory, but the people themselves. Forman’s poetic and inscrutable bits-and-pieces portraits give us as much as any history truly can: a series of discreet and questionable revelations, a public figure in figurine.

***

A native of a decaying Pennsylvania steel town (the one from the Billy Joel song), Emily Kiernan writes about islands, vaudeville, implacable but unjustified feelings of abandonment, the West, and places that aren’t the way she remembered them. Her fiction has appeared in Pank, The Collagist, Atticus Review, Cobalt, and other journals. More information can be found at emilykiernan.com

Tags: Alex Forman, Emily Kiernan, Slim & Erect: Portraits of the Presidents, Tall

this book sounds awesome, thanks for the review