I’ve read some interesting books and magazines over the past couple weeks so I’m going to talk about them in one big post. Also, I’m giving several books away.

They Could No Longer Contain Themselves

I don’t care for the term flash fiction. I understand the etymology but I often think, “Why not call it a story?” There are so many terms now for different kinds of fiction. There is an obsession with naming, creating taxonomies so we can better understand the nature of a thing. Flash fiction. Very short stories. Sudden fiction. Microfiction. Nanofiction. All these terms strive to categorize the nature of stories that fous on brevity and compression. Ask five different writers how to define flash fiction and you will likely hear five different definitions. I read an article in the most recent issue of The New Yorker about tiny houses, and the writer talks about the article’s main subject, this guy named Shafer who designs tiny houses and the writer says, “What makes Shafer’s houses different from others is the classical elements of form and proportion and the graceful compression of his design.” I kept thinking about that line as I thought about the stories in They Could No Longer Contain Themselves. They each contain the classical elements of good fiction and the compression in each story is also graceful like a tiny house that holds everything you need to feel at home.

In They Could No Longer Contain Themselves, the latest book from the reliably excellent Rose Metal Press, five writers offer five unique interpretations of flash fiction in chapbooks by Mary Miller, Elizabeth J. Colen, John Jodzio, Tim Jones-Yelvington, and Sean Lovelace (I reviewed his chapbook in 2009, here).

I am always excited to reading anything by Mary Miller so I read her chapbook, Paper and Tassels, first. Although I had read many of the stories in the magazines where they originally appeared, the writing in the sixteen stories from Paper and Tassels was still fresh. I am intrigued by the way Mary Miller writes women–they often have this affect, this muted relationship with emotion I find endlessly readable. She’s an elegant writer and I love the control in her stories, how the women she writes are often in these awkward relationships. Her characters are women who understand their circumstances, the impossibility of them, and endure those circumstances anyway. Elizabeth J. Colen’s chapbook, Dear Mother Monster, Dear Daughter Mistake, was also outstanding, the stories evoking that graceful compression I mentioned earlier, detailing the complex relationships between mothers and daughters, the inner conflicts of women. The writing here was crisp, not a word or idea out of place. I often found myself holding my breath as I read these stories because they held so much tension. In “Natural Selection,” a mother asks the narrator, a mother herself, to look after her daughter for a moment. When the girl kicks her legs, the narrator drops the child and as the child cries, the narrator takes her husband’s hand and walks home. It’s a perfect terrible moment. In Terminal, the mother is older. Her daughter is older. She is picking up her child, Carrie, at the airport, having returned from her father’s and an illicit trip to Mexico where she slept with three boys. The mother laments that her daughter didn’t tell her about the trip, “That she let them fuck her because she liked the way they smelled after swimming, when the salt water replaced their boy smells and made them taste like men.” Tim Jones-Yelvington’s Evan’s House and The Other Boys Who Live There worked really well as a fully realized project. Jones-Yelvington does a fine job of capturing young boyhood and, in particular, young boys who don’t yet understand what they want. This book was a welcome surprise.

One Story Issues 148, 149, 150, 151

The great thing about One Story is that each issue is very manageable. They only publish one story at a time. The issues also fit nicely in a pocket. The writers published in One Story generally tell great stories and that’s probably what I like most about the magazine. I am confident I will read an impeccably written, engaging story when I pick up an issue. The magazine can be uneven and I am not always excited by the stories as I would like to be but there’s a lot to be said for competence. One Story 148, “A Picture With Yuki,” by Miroslav Penkov, tells the story of a Bulgarian man and his Japanese wife, Yuki, visiting his family in Bulgaria while also seeking fertility treatments. There’s a lot of story packed into the thirty pages of this story–how the couple met, who they are with each other, the conflicts they share. What I loved about this story is that I actually was surprised because it did not end up being a story about marriage or fertility even though that was how the narrative was set up in the early going. The couple goes to the home of the husband’s grandparents and they settle into a quiet rhythm as he relives childhood memories. Then, there is an accident and I don’t want to give too much away, but the ending is subtle and devastating. In “Partisans” (149) by Karl Taro Greenfeld, there is also subtlety by way of a thick, suffocating but slow building horror in a story about mostly unprepared, conscripted soldiers at a remote outpost in a desert protecting unknown ideals in an unknown land from unseen partisans, themselves, the wild around them. We’re given just enough information to make sense of the terrible circumstances in this story and that spareness really works to elevate the fear and tension and impossibility. The ending could have been bloody and disturbing but instead, it was quiet and that was a really smart choice. “Tigers,” (150) by Nalini Jones is a story about an Indian mother who finds a lump in her breast just as her daughter, son-in-law, and grandchildren are nearing the end of their visit with her in India. This story hits all the right notes about children who live far away from parents in different countries, the loneliness of aging, the desperation of love. Essie, the narrator’s wry observations are really wonderful. She doesn’t care for her son-in-law, a man whose “pale, pinkish skin reminded Essie of chicken not cooked long enough,” and for whom, “She had adjusted her speech in his presence, talking loudly and slowly, using smaller words. But her efforts had no effect and eventually she realized that conversation with her son-in-law would always have a shapeless quality, like sinking her fingers in a lump of dough.” I did not love “Water Party” (151) by Kristi Reilly. The writing was fine but the story made little sense to me. An American woman works for an NGO in Ethiopia. Her hair is dirty all the time. She and her roommate decide to throw a water party. She’s having an affair with a married man who breaks her heart (as they always do). I’m being sort of pithy here but that’s the gist of the story. The ending was strong but the story building up to that ending lacked something to make it feel unique. I kept feeling I had read this story before. The American abroad trope feels a bit worn sometimes.

Fugue 40

After the intense discussion about the Fugue “Play” issue, I wanted to read it for myself. The issue, on the whole, is fantastic, one of the better issues of a magazine I’ve read in a while. That said, the Martone piece as footnotes inserted into the writing of others did not work. It was distracting until it became inconsequential. By the middle of the issue, I ignored the footnotes entirely. There was no sense of play to the conceit and in certain pieces, the footnotes really did alter the texts and not in a playful way. I am baffled by what the editors were thinking. If they were going for play, I would have loved to see the footnotes at the top of the page or on the side or center margins, or hell, inserted into pages as drop quotes. If you’re going to play, play.

The great stuff in this issue, though, is really great.

Anne Panning’s “On Personal Frictions & Discontinuities, or, How Reading Montaigne Temporarily Messed With My Mind,” is a witty poem as list as accounting as non sequitur. The strangeness and how the writer plays with form works really well.

Ander Monson has a fantastic essay about books and remixing and more. The essay starts by talking about the Finally Fast commercial, the terribleness of it, and how people have parodied the commercial. He writes, “We like to mock things, to make things, to shock things into understanding, as long as we can share what we (re)make with others.”

Monson also talks about how we’ve forgotten about how it feels to actually produce a book, saying:

What I’m saying is that we’ve forgotten how it can feel to make a book. I don’t mena just how it feels to write a book, but how it feels to make one. Our experience with the codex has been so long and largely mediated—through programs designed to process words like Microsoft Word through which we are able to apparently produce virtual words on virtual pages with virtual drop shadows suggesting the depth of a physical page, which are then saved in ones and zeroes encoded magnetically or optically on hard drives or flash media. We would do well to reconnect with what books feel like in the hands, what they smell like, what the pages sound like when they flex, friction and turn, what they are or can be. We’ve allowed our publishers to do the thinking about a lot of this. We’ve let our editors do the editing; our word processors, the word processing; designers the designing; production mangers, the production; marketers, the marketing; eight maids-a-milking, a typewriter lodged high in a dead tree. The bad news is that many, if not all of these roles are devolving back to writers.

The entire essay is required reading for anyone thinking about books, how and why we make books and what the future of books might look like.

I also loved S.L. Wisenberg’s “Where Is It Written The Sadness of the World?” which does some interesting things with multiple narratives all leading toward the same place. The primary story is about a girl who becomes a woman and her brother who kills himself but it’s also a story about Simone Weil, Joseph (biblically, coat of many colors), Judaism, choices, sex, and all these themes are interwoven in a fascinating way.

It is worth buying the issue for Rachel Yoder’s “Some Really Disgusting Essays About Love.” I had a chance to hear Rachel read this piece at the Mission Creek Festival in Iowa City earlier this year where we read together for Defunct so there is a little bias, perhaps, but that doesn’t negate the excellent writing. The piece is an odd series of little essays about writing but not in the way you think. For example, “The Non-Story is a story with no climactic moment and no point, usually told with gestures of great enthusiasm. It’s what happens sometimes when writers become happy: their forms fall apart and they must find new ways of expressing this strange and uncomfortable way of feeling.” Also: “I write everything in the fourth person point of view. To master this technique, simply imagine you’re a writer and then write from the perspective of that imagined writer about a self you imagine the imagined writer to imagine herself to be.” There is some great commentary about writing and life and unicorns amidst the absurdity.

Whenever I know an issue takes on a theme, I often spend more time than necessary trying to understand how each story, poem, and essay connects to the theme. With this issue, I didn’t really have to do that. I was able, in considering how the issue worked as a whole, to see how the editors were commenting on and interpreting this notion of play. At the beginning of the issue, the editors offer a brief note that the issue was designed to “show how writers are beautifully and smartly playing with genre, form, content, and idea.” They succeeded with only one confusing exception.

Short Dark Oracles by Sara Levine

I wasn’t familiar with Levine’s writing before picking up this book. Her writing reminds me of Amelia Gray in many ways–imaginative and elegant, often darkly humorous. Every story in this small collection is wonderful. My favorites were, “Baby Love,” about a mother realizing that her baby is becoming less a part of her as he grows and also realizing that this significant experience of having a baby is only significant within her domestic sphere, and not as much in the world beyond the one she has created for her family. “More and more, the baby exhibited a personality neither wholly pliable nor designed to reflect the fact that life, as his mother orchestrated it, was perfection itself.” In “The Good Woman,” a woman starts giving all her extra things to the Salvation Army and her generosity becomes a compulsion until she gives away everything in her life. A working mother realizes she can bring small fortunes to herself, in “The Promise,” by telling her young daughter things, great and small, about life. In all of these stories, Levine treats the extraordinary and nearly implausible with calm and control but more than that, these stories speak in unique ways to modern life but do so without the tedious gravity of sermons.

darkly humorous. Every story in this small collection is wonderful. My favorites were, “Baby Love,” about a mother realizing that her baby is becoming less a part of her as he grows and also realizing that this significant experience of having a baby is only significant within her domestic sphere, and not as much in the world beyond the one she has created for her family. “More and more, the baby exhibited a personality neither wholly pliable nor designed to reflect the fact that life, as his mother orchestrated it, was perfection itself.” In “The Good Woman,” a woman starts giving all her extra things to the Salvation Army and her generosity becomes a compulsion until she gives away everything in her life. A working mother realizes she can bring small fortunes to herself, in “The Promise,” by telling her young daughter things, great and small, about life. In all of these stories, Levine treats the extraordinary and nearly implausible with calm and control but more than that, these stories speak in unique ways to modern life but do so without the tedious gravity of sermons.

Damascus is a bar in San Francisco owned by Owen, a middle-aged man who drinks too much and has a terrible birthmark on his upper lip that makes him resemble Hitler so he starts wearing a Santa costume fulltime to create a new focal point in his appearance. He has a niece, Daphne, his only family and Daphne has a friend, Syl, who creates an art installation in the bar involving dead, rotting fish and portraits of fallen soldiers, to protest the war. The year is 2003. George Bush is still president. The world is changing. The wars in Iraq and Afghanistan are only just beginning and this really fast, engaging novel, tells the story of the denizens of Damascus—Owen, Daphne, Syl, Shambles, a divorcée and “the patron saint of handjobs,” No Eyebrows, a man with Stage 4 lung cancer who has abandoned his family to die, Revv, the bartender who works with Owen, and Byron Settles, an honorably discharged Marine who was injured on his first day in Iraq. This novel has a lot of heart and the writer shows real tenderness toward these damaged and imperfect people who are lonely and desperate but still clawing forward from one day to the next. There are many ways to write about war and I like how Mohr approaches the topic through art as protest and what the consequences of such protest might be. The only misstep in this novel was an omniscient, unnamed narrator who inserted himself into the narrative occasionally in a way that made no sense to me. The story did not need that narrative device and I wonder about that choice . An interview with the author is forthcoming and I’ll be asking him about that.

Damascus is a bar in San Francisco owned by Owen, a middle-aged man who drinks too much and has a terrible birthmark on his upper lip that makes him resemble Hitler so he starts wearing a Santa costume fulltime to create a new focal point in his appearance. He has a niece, Daphne, his only family and Daphne has a friend, Syl, who creates an art installation in the bar involving dead, rotting fish and portraits of fallen soldiers, to protest the war. The year is 2003. George Bush is still president. The world is changing. The wars in Iraq and Afghanistan are only just beginning and this really fast, engaging novel, tells the story of the denizens of Damascus—Owen, Daphne, Syl, Shambles, a divorcée and “the patron saint of handjobs,” No Eyebrows, a man with Stage 4 lung cancer who has abandoned his family to die, Revv, the bartender who works with Owen, and Byron Settles, an honorably discharged Marine who was injured on his first day in Iraq. This novel has a lot of heart and the writer shows real tenderness toward these damaged and imperfect people who are lonely and desperate but still clawing forward from one day to the next. There are many ways to write about war and I like how Mohr approaches the topic through art as protest and what the consequences of such protest might be. The only misstep in this novel was an omniscient, unnamed narrator who inserted himself into the narrative occasionally in a way that made no sense to me. The story did not need that narrative device and I wonder about that choice . An interview with the author is forthcoming and I’ll be asking him about that.

This Is Not Your City by Caitlin Horrocks

This is the short story collection I’ve been recommending most lately. This Is Not Your City is a tight, tight collection of short fiction. As I read through this collection I noticed that nearly every story adopts a unique narrative style. You rarely find this much range in a collection because many writers find a certain style or thematic approach and stick to that. My favorite story was “Embodied,” about a woman is living her 127th life as an auditor in Des Moines and when she gives birth to her first child, she recognizes him as someone who wronged her in a previous life. We know early on that she no longer has her son, Jacob, and as the story unravels, we learn why as well as who she was in her 126 previous lives. She explains why she doesn’t attend church, saying, “They’re just Catholics with no pope, and I haven’t died for five separate faiths just to turn around and attend a church that only exists because some English king wanted to trade up on wives.” Horrocks is a really talented writer. She clearly puts a lot of time and research into her stories and is not afraid of exploring diverse circumstances–a single woman in Greece who has an affair with a young drug addict, a teenage girl who befriends an Amish woman, an older couple with a disabled child on a cruise ship that has been pirated by Somalis, a mother and Russian mail-order bride in Finland who helps her only child hide a terrible accident. Regardless of the circumstances in these stories, there are consistencies. The women she writes are often displaced, often struggling to find or understand themselves, often learning that love is complex and requires unexpected sacrifices, sometimes great, sometimes small.

this collection I noticed that nearly every story adopts a unique narrative style. You rarely find this much range in a collection because many writers find a certain style or thematic approach and stick to that. My favorite story was “Embodied,” about a woman is living her 127th life as an auditor in Des Moines and when she gives birth to her first child, she recognizes him as someone who wronged her in a previous life. We know early on that she no longer has her son, Jacob, and as the story unravels, we learn why as well as who she was in her 126 previous lives. She explains why she doesn’t attend church, saying, “They’re just Catholics with no pope, and I haven’t died for five separate faiths just to turn around and attend a church that only exists because some English king wanted to trade up on wives.” Horrocks is a really talented writer. She clearly puts a lot of time and research into her stories and is not afraid of exploring diverse circumstances–a single woman in Greece who has an affair with a young drug addict, a teenage girl who befriends an Amish woman, an older couple with a disabled child on a cruise ship that has been pirated by Somalis, a mother and Russian mail-order bride in Finland who helps her only child hide a terrible accident. Regardless of the circumstances in these stories, there are consistencies. The women she writes are often displaced, often struggling to find or understand themselves, often learning that love is complex and requires unexpected sacrifices, sometimes great, sometimes small.

Lucky Fish by Aimee Nezhukumatathil

In Nezhukumatathil’s third collection, written in three parts, she takes on motherhood, marriage, race, politics, and culture. I am not much of a poetry reader but I really enjoyed this collection and especially Parts Two (Sweet Tooth) and Three (Lucky Penny), where the writing takes on a stronger emotional quality. There are two standout poems in a collection of strong poems–“Dear Betty Brown” and “Birth Geographic.” In the former, Nezhukumatathil takes on Texas representative Betty Brown who in 2009 suggested Asian Americans should change their names to make them more pronounceable for Americans: If I didn’t change my name for my husband,/I’m certainly not going to change it for you./You can take the time & earn it like/everyone else. I know five-year olds/who can say it without a stutter or hiccup./ In “Birth Geographic,” the poem sequence tells the story of the birth of her child interwoven with stories about birth in the countries of her parents–India and the Philippines. There is a lot going on in this poem in terms of language, syntax, the use of space as stanzas spread across each page–truly unforgettable. An interview with the poet is also forthcoming.

In Nezhukumatathil’s third collection, written in three parts, she takes on motherhood, marriage, race, politics, and culture. I am not much of a poetry reader but I really enjoyed this collection and especially Parts Two (Sweet Tooth) and Three (Lucky Penny), where the writing takes on a stronger emotional quality. There are two standout poems in a collection of strong poems–“Dear Betty Brown” and “Birth Geographic.” In the former, Nezhukumatathil takes on Texas representative Betty Brown who in 2009 suggested Asian Americans should change their names to make them more pronounceable for Americans: If I didn’t change my name for my husband,/I’m certainly not going to change it for you./You can take the time & earn it like/everyone else. I know five-year olds/who can say it without a stutter or hiccup./ In “Birth Geographic,” the poem sequence tells the story of the birth of her child interwoven with stories about birth in the countries of her parents–India and the Philippines. There is a lot going on in this poem in terms of language, syntax, the use of space as stanzas spread across each page–truly unforgettable. An interview with the poet is also forthcoming.

American Masculine by Shann Ray

I did not love American Masculine. I will be writing about this book in greater depth elsewhere but here, I’ll say the writing is fine (lots of gorgeously crafted sentences) but the book fell flat. The collection prioritized form and craft over function. Too many of the stories seemed too similar–the same landscape, the same tense, tightly drawn emotional quality to the stories, the same pacing, the same themes. I don’t even mind that so much, but few of the stories really grabbed me in my gut so it was hard to forgive the similarities across many of the stories. The collection’s title was curious given that “American Masculine” is not a title of a story in the book. Sometimes titles really shape how a book will be read so I went into this story thinking about those two words and wondering if the title was thematic foreshadowing, wondering if the stories were making some kind of commentary on Americanism or masculinity. I don’t think the writing was making a statement even though the stories certainly tried. That might be my primary frustration. The men in these stories are rugged and tall. Their size comes up over and over again and I’m not sure why but suffice it to say, most of the men in this book are over six feet tall. There are many hard drinkers and brutal fathers and lost men. Ray captures the modern American West quite nicely–the lanscape in this collection is a character unto itself, perhaps too much of a character because it doesn’t leave enough room for anything else. There are a few notable stories–“Rodin’s The Hand of God: A Triptych,” is a masterful story about a father who keeps trying to save his daughter after her two children die in a car accident and she survives. The daughter tries to commit suicide multiple times, is merely existing between attempts, and the father is trying to redeem himself as a father too late for his efforts to really matter. The way he loves his child so deeply, so carefully, is perfectly written. The narrative form of three panels works well. I also appreciated “Mrs. Secrest,” about a husband and wife at the point in their marriage where the wife is considering an affair with her boss and the husband knows. “How We Fall,” tells another story about a troubled marriage, about lost people struggling with addiction who eventually find each other again. It was interesting that many of these stories were hard stories about hard circumstances but also had happy endings. That was an unexpected choice. This is one of those collections where I know the writer is talented and can see the intelligence of the collection but still want more. In this case, I wanted more depth and texture and range from the stories. I’d love to know what others thought of this book.

I did not love American Masculine. I will be writing about this book in greater depth elsewhere but here, I’ll say the writing is fine (lots of gorgeously crafted sentences) but the book fell flat. The collection prioritized form and craft over function. Too many of the stories seemed too similar–the same landscape, the same tense, tightly drawn emotional quality to the stories, the same pacing, the same themes. I don’t even mind that so much, but few of the stories really grabbed me in my gut so it was hard to forgive the similarities across many of the stories. The collection’s title was curious given that “American Masculine” is not a title of a story in the book. Sometimes titles really shape how a book will be read so I went into this story thinking about those two words and wondering if the title was thematic foreshadowing, wondering if the stories were making some kind of commentary on Americanism or masculinity. I don’t think the writing was making a statement even though the stories certainly tried. That might be my primary frustration. The men in these stories are rugged and tall. Their size comes up over and over again and I’m not sure why but suffice it to say, most of the men in this book are over six feet tall. There are many hard drinkers and brutal fathers and lost men. Ray captures the modern American West quite nicely–the lanscape in this collection is a character unto itself, perhaps too much of a character because it doesn’t leave enough room for anything else. There are a few notable stories–“Rodin’s The Hand of God: A Triptych,” is a masterful story about a father who keeps trying to save his daughter after her two children die in a car accident and she survives. The daughter tries to commit suicide multiple times, is merely existing between attempts, and the father is trying to redeem himself as a father too late for his efforts to really matter. The way he loves his child so deeply, so carefully, is perfectly written. The narrative form of three panels works well. I also appreciated “Mrs. Secrest,” about a husband and wife at the point in their marriage where the wife is considering an affair with her boss and the husband knows. “How We Fall,” tells another story about a troubled marriage, about lost people struggling with addiction who eventually find each other again. It was interesting that many of these stories were hard stories about hard circumstances but also had happy endings. That was an unexpected choice. This is one of those collections where I know the writer is talented and can see the intelligence of the collection but still want more. In this case, I wanted more depth and texture and range from the stories. I’d love to know what others thought of this book.

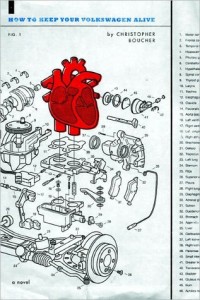

How to Keep Your Volkswagen Alive by Christopher Boucher

This novel plays with language and form and at times, the level of experiment is overwhelming but I can truly say I’ve never read anything like How to Keep Your Volkswagen Alive. It is not often I can say that about a book. The structure follows that of the maintenance manual by the same name. The very first chapter offers instructions on how to use the book replete with a list of preliminary tools: “One book about Volkswagens (a buildings-roman-itself; a coming of age and highwaying; an okay, if you say so, yes), at least two good hands, one driving forward, a missing you can’t meet, one reading heart, twelve gallons of liquid Haymarket-invention chai (No substitutions. you can taste it yourself—there is no replacement for the Haymarket!), one basement kitchen, set for cold and dark and buggy, and as many Volkswagen Beetles as you can find. Oftentimes I struggle with experimental writing because I love emotional writing and the two rarely seem to be able to co-exist. Such is not the case in this book which is a story about a single father of a 1971 Volkswagen Bettle who is mourning the death of his father and trying to keep his son car alive. This book creates its own language that is dense and, at times, frustrating but there is so much intelligence and heart in this book that you won’t regret sticking with this book. Boucher’s first novel is one of the most original books you will read this year.

This novel plays with language and form and at times, the level of experiment is overwhelming but I can truly say I’ve never read anything like How to Keep Your Volkswagen Alive. It is not often I can say that about a book. The structure follows that of the maintenance manual by the same name. The very first chapter offers instructions on how to use the book replete with a list of preliminary tools: “One book about Volkswagens (a buildings-roman-itself; a coming of age and highwaying; an okay, if you say so, yes), at least two good hands, one driving forward, a missing you can’t meet, one reading heart, twelve gallons of liquid Haymarket-invention chai (No substitutions. you can taste it yourself—there is no replacement for the Haymarket!), one basement kitchen, set for cold and dark and buggy, and as many Volkswagen Beetles as you can find. Oftentimes I struggle with experimental writing because I love emotional writing and the two rarely seem to be able to co-exist. Such is not the case in this book which is a story about a single father of a 1971 Volkswagen Bettle who is mourning the death of his father and trying to keep his son car alive. This book creates its own language that is dense and, at times, frustrating but there is so much intelligence and heart in this book that you won’t regret sticking with this book. Boucher’s first novel is one of the most original books you will read this year.

Free Books:

I have multiple copies of books. I would like to share those books. If you want one of these books, say so in the comments, and if you’re the first to claim a book, e-mail me your name/address at roxane at roxanegay.com. US Residents only because international shipping is crazy expensive.

How to Keep Your Volkswagen Alive (2 1 copies) by Christopher Boucher

Silver Sparrow by Tayari Jones (signed)

Fog Gorgeous Stag by Sean Lovelace

Luminarium by Alex Shakar

Tongue Party by Sarah Rose Etter

Us by Michael Kimball

Re: Telling: An Anthology of Borrowed Premises, Stolen Settings, Purloined Plots and Appropriated Characters

Hard to Say by Ethel Rohan (4 2 copies)

The Heyday of Insensitive Bastards by Robert Boswell

Witz by Joshua Cohen

An Island of Fifty by Ben Brooks

Firework by Eugene Marten

The Convert by Deborah Baker

Green Girl by Kate Zambreno

Tags: Christopher Boucher, Fugue, rose metal press

Can I have Fog Gorgeous Stag please?

I’d like Green Girl.

“Us” by Michael Kimball

I totally want Tongue Party.

An Island of Fifty by Ben Brooks, please.

How to Keep Your Volkswagon Alive?

Hard to Say, Fog Gorgeous Stag. Is it OK to ask for two? I pick Hard to Say if not.

Can I have The Convert?

firework!

Can I please have Hard To Say?

No you can’t ask for two.

Whoops, e-mailed you already, but can I still have the copy of Witz?

I want This Is Not Your City!

It’s great. Sadly, I’m not giving a copy of that away.

Yes.

I would like the second copy of How to Keep Your Volkswagon Alive, please! Thanks!

Katy Perry.

Yes.

Yes.

Yes.

Will do.

Okay.

Yours.

Yes.

Oh, you are not giving that away. Embarrassing. I think I need to have How To Keep Your Volkswagen Alive, too.

Okay.

Send me your address. I’ll send you a copy of This Is Not Your City anyway.

Nice post, by the way. I’ve been curious about Damascus. And Sara Levine’s book has a fantastic cover.

Re: Telling: An Anthology of Borrowed Premises, Stolen Settings, Purloined Plots and Appropriated Characters?

I want silver sparrow!

and retelling! Pleaseeeeeeee

Hey Roxane. If you have anymore copies of Hard To Say, I’d love one.

Can I get a copy of “Hard To Say”?

Luminarium?

I’d like all of them.

Re:telling is great, y’all, Imma vouch for it.

I’d love the Tayari Jones novel. I followed her blog a little bit but haven’t picked it up yet!

I love Sara Levine’s BABY LOVE, it is one of my favorite things Ive read in the internet.

Luminarium

Silver Sparrow?

oh, just realized I forgot to say please.

Please, Roxane…maker of all things good and goddess of beauty!

can i have a copy of ‘hard to say’

Yes.

Yes.

Yes.

No.

Yes.

Yes.

The second copy was already taken when you responded.

The second copy was already taken when you responded.

I like when you say please Corey.

I like when you say please Corey.

Someone claimed it before you, sorry.

Yes.

Yes you can.

Already taken.

That was already taken.

Send your address.

Thanks. Please send me your address.

You need to send your address.

Awesome. Thanks, Roxane.

and that “finally fast” commercial is really, really bad.

Can I have The Heyday of Insensitive Bastards?

Yes. Please e-mail your address.

It really is.

Thanks!

Thanks!

Tongue Party was the most recent thing I read that she was giving away, and you are very lucky! It rules!

http://tinyurl.com/23963mg

do you have any more books you want to give away?

It’s been two days and I haven’t said “thank you.” I feel bad. So I’m finally getting out my gratitude: thanks!

It’s been two days and I haven’t said “thank you.” I feel bad. So I’m finally getting out my gratitude: thanks!

[…] Roxanne Gay on They Could No Longer Contain Themselves. […]