I. On January 13, 2011 a 6-year old boy was killed in downtown St. Petersburg by a giant icicle. This happened a block away from the apartment building where my grandmother used to live, two blocks away from the identical apartment building where my parents still live. The boy was an orphan, living with his grandparents. His grandmother was taking him to an outpatient clinic for a check-up after a recent cold. When he stepped outside his apartment building, the icicle became dislodged from the roof of the building and cracked the boy’s head. His grandmother, emerging from the building directly behind him, collapsed with a heart attack.

I. On January 13, 2011 a 6-year old boy was killed in downtown St. Petersburg by a giant icicle. This happened a block away from the apartment building where my grandmother used to live, two blocks away from the identical apartment building where my parents still live. The boy was an orphan, living with his grandparents. His grandmother was taking him to an outpatient clinic for a check-up after a recent cold. When he stepped outside his apartment building, the icicle became dislodged from the roof of the building and cracked the boy’s head. His grandmother, emerging from the building directly behind him, collapsed with a heart attack.

The next day, the press was astir trying to establish the party responsible for this incident. Who was to blame: the building, the block, the district, or the city administration? For a city located at the latitude of 60°N, St. Petersburg has been criminally poorly prepared for snow. Snow somehow always comes as a surprise in St. Petersburg. A few days after the death of the boy, as a bomb exploded in Moscow’s airport, St. Petersburg had another snow-related disaster: the roof of a mega-market “O’Key” caved in under a giant pile of snow. One person died and seventeen were injured.

Counter to its reputation, St. Petersburg doesn’t enjoy long, cold “Russian” winters. Instead, the flashes of cold weather alternate with periods of thaw, when snow melts forming ice on the ground and ice on the roofs of the buildings, from which snow has not been cleaned off. The last two years saw unusually high levels of snowfall—and the icicles have also grown to massive proportions. Theoretically, cleaning the roofs of the apartment buildings is a daily job. Practically, who is going to pay for it? And where to find workers willing to do the job? Money in the city’s budget allocated toward infrastructure needs has a tendency to mysteriously dematerialize. In the aftermath of the recent deaths, St. Petersburg’s governor Valentina Matvienko has proposed using the homeless as the workforce to clean the snow, and also developing laser technology to get rid of the snow “scientifically.”

II. The news of St. Petersburg’s latest battles with snow gather in my inbox as I’m in the middle of reading and rereading Clark Coolidge’s book-length poem This Time We Are Both, published in 2010 by Ugly Duckling Presse. The title is the first thing that grabs my attention. “This Time We Are Both” implies a previous meeting: when, where, how? And who are the two united in “both”? And how does this proposition end—what are “both” going to do this time? This book, completed in 1991, loosely traces Coolidge’s 1989 tour of the Soviet Union with Rova Saxophone Quartet. The musicians performed in the large halls of Baltic cities—Leningrad, Vilnius, Riga, Tallinn, Tartu—and Moscow. The structure of the book resembles a travelogue, a diary of the trip to the “Second World” on the eve of its collapse. In light of this context, “This Time We Are Both” suggests geopolitical events—the U.S. and U.S.S.R. coming closer together. But I don’t want to rush to any conclusions.

Leningrad is identified by name only in the second of the sixteen sections of the book, but I get a whiff of the familiar air from the first lines. The city of my childhood is dark and smells of industrial factory smoke and cigarettes.

Dark hands pass

dark with no silence

lights in the smoke

hands that start, that light

pass the particles, link penetrations

to an amphitheater smell…

The single word “dark” appears nine times on the first page alone. The season is January, and Leningrad is a dark, dark, dark, dark, dark, dark, dark, dark, dark place: “The never rest dark” “tastes more than dark” “I live dark in particular waiting” “so dark the hands to cross with” “grant dark its plain airs” “dark has its corners” “darkness hurdles the people sleep on showing / off all dreams.” Throughout the poem, the colors of the natural phenomena in this world are browns and greys: “A brown dawn,” “the grey days,” and if one is not careful, “the scald you don’t see can / make your veins steel.” It’s depressing: “all this / cement hurries the sun down.” The smoke from the factories contributes to this darkness, dulls all other colors: “we woke in here on a beam of smoke,” “the field of no light/ backed with smoke,” and after a train trip that allows a rare glimpse of blue sky, the city landscape comes to bear with new force: “I’d forgotten about / the overwhelming factory smoke.”

The sun, when it appears, brings no color, no warmth to the Soviet cities. The sun is utilitarian, necessary to maintain life, “flats of sun fill blind vitamins,” the sun is a source of light, “sun reveals / twigs in bottles,” ultimately ineffective, “sun stalls in its own smoke,” “this smoke over Moscow blows / the sun to shreds.” Green is disassociated from the color of nature, and attaches itself to the notion of time, “the time-green neons,” time that is artificial and moldy, “green linoleum light,” time that greens metal and stone of monuments and bridges: “Green stones the mind wraps its skin in this,” “we are trapped because of bridges their nature / sometimes is to be, some of the time is paint green.”

Only once in a while, a flash of a bright artificial color disrupts this brown-grey world: “lozenge orange trolleys right out / yellow of headlamps show a grammar line to rid lemon / sodas of anciency.” The beginning of section “X” that takes place in Riga reads like a eulogy to the color orange—the orange stripe, all that remains of the orange paint on the wall of a building:

nor longer an orange stripe that once

did have the orange stripe but don’t

what was an orange stripe now isn’t

given the orange stripe no other

orange the stripe of this wall top missed

the orange stripe of a wall so gone

Perhaps the orange is not completely gone, but is still there under a layer of snow. But the prospects look dim:

But pocks of snow, every way

Everything was, over all

It will no longer be?

A little over midway through the trip, the poet erupts in a desperate plea: “will the grey / that’s really blue come through this brown that’s really white?”

III. It’s not common—and perhaps, not appropriate—to discuss Coolidge’s work purely in terms of its semantic meaning the way I’ve done above. Coolidge is an experimental poet, associated with the New York School and L=A=N=G=U=A=G=E poets. Commentators usually focus on Coolidge’s interest in highlighting the semantic distances between words and phrases, the absence of traditional syntax that allows him to create collages of word images, the importance of sound and rhythm to this musician-poet. As Reginald Shepherd commented in his article “On Difficulty in Poetry” (The Writer’s Chronicle, May/Summer 2008), “Clark Coolidge’s poems appear as gibberish to many readers: they present both semantic and modal difficulty. In the case of modal difficulty, a reader asks, ‘What makes this a poem?'” This is particularly true of Coolidge’s earlier poems, for example, the 1973 cycle “Oflengths” with poems constructed almost exclusively of prepositions:

with in been

was

as a this and

was in so in there

The critics of Coolidge’s later works have noted the change in the poet’s usage of language, in his approach to poetry. David Antin, in his 1986 review of Solution Passage, traces the evolution in Coolidge’s work from the “wordscapes, sparse arrangements of single words” in the 1960s to the assembly of “larger units, phrases, phrase groups and sentences in lines to form longer sequences that occasionally seemed to produce bursts of apparently connected speech” in the 1970s to the introduction of a “fairly consistent speaker, an ‘I’ that lasts nearly long enough to govern the entire speech act of the poem” in the 1980s. This Time We Are Both certainly continues this trend: this poem is driven by the speaker’s voice, traces the speaker’s experiences during the concert tour. It appears to have all the attributes of a lyric poem.

Reading Coolidge makes me acutely aware of my own reading practices: my need for sense-making, my attempts to construct a coherent narrative. “So, what was it like to be in Leningrad in 1989?” I interrogate the poem, and then pick a line from the end of the poem for the answer that suits me: “anyway back always to hell out of it all / and never come back.” Never come back, that’s right, never come back to this dark, airless world. Of course, I could’ve picked another line: “Or is it more nuclear to make a mistake?” The speaker is intentionally egging me on: “if you are reading this thinking this is a code, it is / but only to be read up into further codes.”

IV. This is certain: I read Coolidge in the context of my experience, and my experience is grounded in 20th C Leningrad-St. Petersburg poetry.

Here’s Alexander Blok on St. Petersburg in a poem “Snow Maiden”:

Где ветер, дождь, и зыбь, и мгла,

С какой-то непонятной верой

Она, как царство, приняла.

And my iron-gray city,

ridden by wind, rain, and choppy waves, and darkness,

She accepted, with mysterious faith,

like her own kingdom.

Fyodor Sologub:

Ржаво-серым и хмельным.

Петербург с его обманом

Весь растаял, словно дым.

The day wrapped itself in fog,

rust-gray and intoxicating.

Petersburg with its illusion

disappeared completely, like smoke.

Osip Mandelshtam:

Рыбий жир ленинградских речных фонарей,

Узнавай же скорее декабрьский денек,

Где к зловещему дегтю подмешан желток.

You have returned here, so eat up, quick,

the fish-oil of Leningrad’s river lights

Recognize, quick, this December day,

ridden by the sinister tar mixed with yolk

And the poets of 1960s and 1970s: Leonid Aronzon: “не темен, а сер полусумрак [the gathering dusk is not dark, but gray].” Sergei Stratanovsky: “Дым заводской живет в канале [Factory smoke lives in the canal].” Elena Shvartz: “Так погибель здесь все превзошла [Death has risen here above all else].”

The myth of St. Petersburg, a romantic city in the popular imagination, presents a problem for contemporary poets. After the years of the Stalin’s terror campaigns, the Brezhnev-era stagnation and the Perestroika collapse of infrastructure, it has become impossible for poets to perpetuate the idea of Leningrad-St. Petersburg as a modern, forward-looking city—or, at least, to do so in good faith. The mythical gray of St. Petersburg has lost its mysterious, romantic qualities that characterize Blok’s and Sologub’s verse, has become sinister in Mandelshtam’s poetry, and by the second half of the century came to signify the brutal, inhospitable city, an environment incapable of sustaining human life. Coolidge’s work seems to feed from the same source of poetic imagination as the work of his Russian contemporaries; and if he’s searching for escape routes from the dark world he stumbled into, well, everyone else was looking for exits, too.

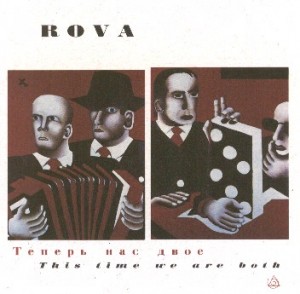

V. The 1989 tour was Rova Saxophone Quartet’s second journey to the USSR, Coolidge’s first. Unlike their unofficial 1983 tour, when the group performed in semi-legal venues, this time, Rova’s appearances were sponsored by Goskontsert, a department of the Ministry of Culture responsible for live shows. Introductions were made to many local musicians, writers, artists. This Time We Are Both, the title of Coolidge’s long poem, was the title of the live record Rova recorded during the 1989 tour. Their concerts during the 1983 tour had been called Saxophone Diplomacy.

The essay accompanying Rova’s live record This Time We Are Both describes a scenario fairly characteristic to most publicized encounters between foreigners and locals at the time. The musicians remember

being escorted by young Russian guides who were openly critical of both their government and the havoc wreaked on their society by 70 years of state socialism. We heard frank stories about black market car lots, ten-year waiting lists for apartments, the cultivation of ‘connections’ for special favors, and the failure of Leninist ideal. ‘Next they are going to run out of electricity,’ quipped our tour leader, Misha, when our bus transportation was jeopardized by a gasoline shortage in Latvia.

The overtones of these conversations and experiences are clearly audible in Coolidge’s poem-travelogue. Coolidge witnesses bribery: “continue to roll / the policemen of their pretense, so threadbare it is.” He reflects on the gas incident: “the advantages of the Soviets / withholding lousy car gas, can’t run, can’t fly, cow out of hand.” He reflects on the tension between Moscow and the Baltic republics: “the red army should come short in Lithuanian time / coats on, shopping over, go home, what else? / it says here in red, it cuts here in slab.”

Like a diary, Coolidge’s poem documents the difficulty of performing everyday activities in the Soviet Union. Having coffee in the morning: “The coffee’s hard and so is the cream, in layers / so is this morning, all I had to head away from / frozen.” Taking a ride in public transportation: “these people become violent on streetcars” or in an elevator, whether it is “the elevator that snaps” or “the elevator / which burned.” Coolidge records his nightmare—or is this a nightmarish incident?—clearly inspired by the stories of government agents spying on everyone: “we got home we found / a turned room and whole house further long / shaken the cement to pink fists.” He describes trips to the museums in Moscow: “the museums roll by, it’s all kept / believing, stained and leaning, the wave of huge blocks / and I’m stumped, deride, assay, Pushkin with Impressionists.”

Reading the track list of Rova Quartet’s album provides another contextual clue to the tight code of Coolidge’s poem. The lines “Terrains tonight rose / so was found space around every / time the globe integers whistle feeler meaning/ no explanation but penetration in a natural / light” most likely refer to the band’s performance of a composition titled “Third Terrain.” The verse: “I imagine chaired by / what was lost stops / what regained stays” clearly has something to do with another track on the album, “What was Lost Regained.” “The unquestioned answer rose tonight too, through / the twins’ mesh into furthers of a whole other two / an unexplored life in that territory hallway” suggests the track “The Unquestioned Answer.” These details of concert appearances are interspersed throughout the book as they were during the tour. What interests Coolidge in these experiences seems to be the interactions of the band members and their music with the audience, the way music penetrates the space of the concert halls and meshes with the lives of the listeners. By the time the group gets to Moscow and the tour nears the end, Coolidge clearly becomes impatient with the desire to rouse the locals to action: “want to stand on ledges, bare fangs, make people/ then raise them loose, make them do things.”

VI. After I discovered the connection between the titles of Coolidge’s book and Rova Quartet’s live album, the line “This Time We Are Both,” became my primary clue in uncovering other literary and extra-literary connections that establish new contexts for reading Coolidge’s poem. Searching for more information, I stumbled across two other books published in 1991 written by people associated with Coolidge’s and Rova’s 1989 tour of the Soviet Union.

In August 1989, a few months before Rova’s winter tour, Leningrad saw an international conference of avant-garde writers. Two years later, in 1991, four American writers who had attended this conference, composed a book of essays, Leningrad: American Writers in the Soviet Union published by Mercury House. The writers were Michael Davidson, Lyn Hejinian, Ron Silliman, and Barrett Watten. Lyn Hejinian was married to saxophonist Larry Ochs, the “O” in “ROVA” Saxophone Quartet, one of the group’s original co-founders. In Russia, Lyn Hejinian developed a very fruitful working relationship with a counter-culture poet and writer Arkadii Dragomoshchenko, whose own work is closely related to the work of American Language School poets. In later years, Hejinian translated two of Dragomoshchenko’s poetry collections to English, and he translated her work to Russian.

Coolidge’s This Time We Are Both is dedicated to Lyn and Arkadii. In interviews, Coolidge cites meeting Dragomoshchenko as one of the highlights of the trip to the Soviet Union. A footnote in the collection “Leningrad” explains that the line “This Time We Are Both” was the title of a painting by Ostap Dragomoshchenko, Arkadii’s son. I think it’s likely that this is the painting that became the cover illustration of Rova’s live album, “This Time We Are Both.” The cover provides the Russian version of the title, “Теперь нас двое.” The Russian and the English titles are printed together visually suggesting that they mean the same thing in different languages. But the Russian words don’t translate into “This time we are both”—not exactly. I would render them in English as “And now we are two.” The phrase is something of a romantic cliché—it implies that before “we” didn’t know each other, “we” were going about our separate ways, but something happened—”we” met—”And now we are two.” It implies a state of arrival, the happy ever after, and perhaps a future union with even more friendly parties—the makings of a group. One can imagine that “we” might become three or four or many more. The two phrases are distinctly different. This line that Coolidge took for the title of his book— is it a case of mistranslation, of miscommunication? Is the confusion, the semantic distance between the two phrases intentional? Where the Russian title suggests a happy end, the English title is a beginning of a new phase in a long and complicated history.

VII. In a 1991 interview, Dragomoshchenko said: “Ленинград—деревня. Ну, может быть, каменная деревня. … И люди тоже себя ощущают каменно. … И вода каменная. [Leningrad—is a country village. Well, maybe a stone village. … And the people also experience themselves as made of stone. … And the water is stone].”

Lyn Hejinian used the words “This time we are both” in a long poem of her own. In 1991—clearly a very productive year for this group of people—she published a book called “Oxota: A Short Russian Novel.” (Oxota is transliteration from Russian for “a hunt.”) According to the commentator Marjorie Perloff, the book opens when “the narrator (“Lyn”) arrives in Leningrad to stay (as we know from later poems) with Russian poet Arkadii Dragomoschenko, whom she is translating.” “This time we are both” are the opening words to this book in the stanza as follows:

The old thaw is inert, everything set again in snow

At insomnia, at apathy

We must learn to endure the insecurity as we read

The felt need for a love intrigue

There is no person—he or she was appeased and withdrawn

There is relationship but it lacks simplicity

People are very aggressive and every week more so

The Soviet colonel appearing in such of our stories

He is sentimental and duckfooted

He is held fast, he is in his principles

But here is a small piece of the truth—I am glad to greet you

There, just with a few simple words it is possible to say the truth

It is so because often men and women have their sense of honor.

Hejinian’s reflection on the locals who are “very aggressive and every week more so” resonates with Dragomoschenko’s assessment of Leningrad residents who “experience themselves as made of stone.”

This text provides another context for reading Coolidge’s poem: that of complicated personal relationships between the protagonists of Hejinian’s “Short Russian Novel.” Coolidge himself was perhaps one of the minor characters, and yet affected by the experience strongly enough to return to it in his own poetic text, the relationship signified by the same line, “This time we are both.”

The line makes one more appearance, this time as a line in the body of Coolidge’s long poem. It’s sandwiched near the end of a stanza, between two bird images, a parrot and a crow—a parroting of the words of others, and a sinister crowing:

that and a carrot juice

to fall over forward, gypsum, famous

and yet find a different route, a parrot

this time we are both

By the things that the man had brought to his cell

I learned that the grey and black birds are crows

there was a guy back there in a long coat

A “cell”? “A guy back there in a long coat”? Perhaps the Soviet colonel from Hejinian’s poem. He’s clearly up to no good, a sinister presence, someone who always hangs around in the background.

VIII. I started this review with St. Petersburg of today and its battles with snow and ice that, like everything in St. Petersburg, begin and end with local and national politics. In the days I’ve been working on this, the local news have reported yet another snow-related incident: a large chunk of snow cleaned from the roof of a building fell on a baby carriage. By chance, the baby was not hurt other than a few head scratches, and the terrified mother alerted all the authorities and news media. Will this do any good? Today, witnesses from a central city district are reporting seeing workers cutting ice and snow from the streets with gasoline-powered saws—making an effort at cleaning the streets for the first time this winter. Will these workers come back to continue the job tomorrow?

Of course, Leningrad and the Soviet Union of Coolidge’s long poem is a world of different order from the St. Petersburg of this news reel; it signifies primarily by being read in the context of American, English-language poetics, and by its relationship to Leningrad and the Soviet Union of American popular imagination. And yet what makes Coolidge’s text particularly remarkable is the richness of its connection to the contemporary Russian culture, its ability to signify within the Russian contexts of reading. This Time We Are Both is not a work of a cultural tourist, and neither is it a work of an artist whose sole interest is in creating wordscapes. In this long poem, Coolidge is a mature poet who is aware not only of the deep cultural contexts of his words, but also is aware of his poetry being read in political contexts. To inaccurately paraphrase him once again, when “snow goes on the overblown way” and “the planet of hinges [is] buried to its edges,”—”use your icicles.”

***

February 12, 2011

Olga Zilberbourg is a fiction writer and editor traveling between San Francisco, CA and St. Petersburg, Russia. Her second Russian-language collection of stories was published in September 2010 by St. Petersburg-based Limbus Press. In English, her stories have appeared in Narrative Magazine, Alligator Juniper, J Journal, and other publications. She blogs about travel and writing at www.zilberbourg.com.

“This time we are both” can mean ‘this iteration, we two are, together, going to do the same thing’, as you suggest.

I think the “this time” must mean there was/is at least one other time, and usually we use the “this” to refer to the subsequent time – the other time was an earlier one.

But the “we” can refer to any number of (let’s say) people greater than one, and “both” might introduce states of being, adjectives, rather than actions. For example: ‘This time, we (each of ten) are both late and wet (arriving at the bar).’ – Not so much that a duality is “united” in some activity, but rather, that a multitude experiences or participates in the same two conditions.

—–

You quote the record sleeve (?) concerning “the havoc wreaked on [the citizens of the Soviet Union] by 70 years of state socialism“. Why do the musicians put the hat on “socialism”??

Lots of us – some following Dunayevskaya, to some extent – think of Soviet “socialism” as General Motors with its own terror-enabled police force.

When I read “Money in the city’s budget allocated toward infrastucture has a tendency to mysteriously dematerialize.”, I thought: Gee, that never happens here! – ha ha ha.

But I also wondered if there are people in Russia who have bags of tea tied in their hair, people who don’t ‘believe’ that socialized infrastructure exists.

A favorite scrap of Petersburg/Leningrad poetry, for me, is the “Instead of a Preface” to Requiem:

Petersburg is an important topos in Akhmatova’s poetry. Her “Poem Without a Hero” is almost entirely dedicated to it. Here are a couple of Russian-language essays about it: http://www.akhmatova.org/articles/stepanov1.htm, http://www.akhmatova.org/articles/articles.php?id=25, http://literatura5.narod.ru/ahmatova.html

Dear customers, thank you for your support of our company.

Here, there’s good news to tell you: The company recently

launched a number of new fashion items! ! Fashionable

and welcome everyone to come buy. If necessary,

welcome to :===== www. soozone.com========

italy pride bracelet

Use Your Icicles: A Review of This Time We Are Both by Clark Coolidge | HTMLGIANT

[…] “Use Your Icicles”: A Review of This Time We Are Both by Clark Coolidge […]