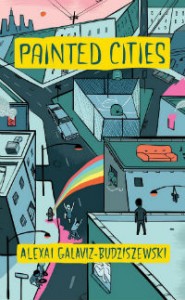

Painted Cities by Alexai Galaviz-Budziszewski

Painted Cities

Painted Cities

by Alexai Galaviz-Budziszewski

McSweeney’s, March 2014

180 pages / $24 Buy from Amazon

Painted Cities is the kind of book that gives me hope. This isn’t the best thing I can say; the best books I read take away my hope altogether, blow me away so thoroughly that I can’t imagine ever writing anything that can even appear in the same medium as them. The best books crush me, leave me in awe.

But hope is not the worst thing I can say, either. The stories in Painted Cities are loose and optimistic. As promised by the sticker plastered to the back of the book, they chart a (usually) first-person narrator’s coming of age in the Pilsen neighborhood of Chicago, where illicit trysts are as likely to happen in the adjacent apartment as shootings are to take place just down the street. The first full story in the collection—it’s preceded by a three-page short, the likes of which are peppered throughout the collection—works in the continuous past, out of scene, for ten pages. The narrator and his sister used to pan for gold in the gutter; they would find 7UP tops and cut their hands on shattered glass. We hear about the neighborhood in an almost endless series of sentences like these, this one describing the parties neighborhood kids had around unscrewed fire hydrants: “From where our pump was, the kids down the block looked like miniature figurines, pet people running about, yapping, like windup toys.” It is only in the final three pages that a nearby apartment building burns down, and the narrator’s family piles into the street to reflect on the ruin that almost seems built in to the tightly-packed Pilsen apartments.

This is what I mean when I say loose. The stories here don’t seem overly concerned about developing a plot. They seem unworkshopped, something that bothered me at first and later, when I thought about it, turned into a virtue. It’s clear that the point of Painted Cities, like its presumable namesake, Calvino’s Invisible Cities, is more the environs than the action that occurs therein. It strikes me as victorious—it gives me hope—that a debut story collection can survive, even thrive, on the sheer, naked power of wonder at the neighborhood the author grew up in.

Some other cases in point. In “Freedom,” the narrator and his newfound friend Buff climb to the top of an old pierogi factory and build a fortress out of scrap wood, imaginatively thriving there until some gangbangers climb up and tear it down. “Maximilian” proposes, “I want to tell you three memories of my cousin Maximilian,” and goes on to do just that. “Blood,” in the guise of a barroom narrator speaking to a second-person listener, riffs on bar etiquette and interpolates events that took place in the bar and the surrounding neighborhood. The five-page “Supernatural” describes the uncanny light that wafts from a polluted river at sundown, and the crowds that are drawn to it.

Even the titles here give off a sort of pleasant naiveté, the possibility that experiences might be reduced to a single salient buzz-word. Of course, the stories’ depiction of a world that is self-consciously less than perfect puts the tongue of titles like “Growing Pains” and “Ice Castles” fairly well in cheek. But still, you see an almost overly earnest impulse in Galaviz-Budziszewski to redeem Pilsen, to make something brighter emerge from its grittiness. At the end of “Blood,” we get:

You got a good friend, that means you do anything for them. That’s being stand-up….A friend’s all you got, they’re family, and once you don’t got family, tell me, motherfucker, what do you got? (128)

At times I’m skeptical. Galaviz-Budziszewski’s biography in the back of the book is self-consciously external not only to the academy many of us are used to but to the publishing world at large. It reads in full:

Alexai Galaviz-Budziszewksi grew up in the Pilsen neighborhood on the south side of Chicago. He has taught in the Chicago public school system and is currently a high school counselor for students with disabilities. In his spare time he builds and repairs motorcycles.

I worry that Galaviz-Budziszewski is trading on his worldliness here, trying too consciously to cultivate a persona that is qualified to speak about the struggles of inner-city life. But when you get the object in your hands, you’ll forgive him quickly. Painted Cities is a beautiful, short book, 180 pages between hardcovers (no dust jacket) that are illustrated wonderfully by Joel Trussel. Galaviz-Budziszewksi is so trusting with his narration, so endearingly willing to pull a thin yarn the length of twelve pages, that you can’t help but like the guy.

And when you get stories like “God’s Country,” the longest in the collection by far at thirty pages, you begin to think that you might be able to do this too. This is where the hope comes in. The story follows a boy who discovers one day that he is able to bring dead creatures back to life. He and his friends spend a summer reviving pigeons, finally bring an OD’d gangbanger back from the beyond.

The end of the story felt like too much to me at first, the kind of sweet wrap-up that a young writer wants to give their stories to cauterize frayed ends. Even today, the retrospective narrator says, when he finds a dead bug in his bathroom he’ll pretend to be his supernaturally powerful friend:

And just for fun I’ll close my eyes, open them, and touch the dead body. I’ll hope that my finger will give life, that I’ll feel again what I felt when I was fourteen, when, in this whole damn neighborhood, among all this concrete, all these apartment buildings, church steeples, and smoke stacks, we were somebody.

But then I let go of my skepticism and let the story be what it is. What is it? A guy remembering what it was like to grow up and wishing, despite the turmoil, that he was still there. That’s something I can appreciate, long string of nostalgic commas or not. And it’s something—this is my favorite part—that I think I might be able to do someday too.

***

Dennis James Sweeney‘s writing appears in recent issues of Word For/Word, Harpur Palate, Unstuck, and Fjords Review‘s Monthly Flash Fiction. He lives in Corvallis, Oregon. Find him at dennisjamessweeney.com.

May 19th, 2014 / 10:00 am