Herschel Hoffmeyer, Dinosaur Enthusiast

“I’ve been learning about and drawing dinosaurs since I was a kid,” explains Herschel Hoffmeyer, creator of the Apex Theropod Deck-Building Game, now on Kickstarter. “I even won a dinosaur art contest at a local library when I was very little. I was made to create these guys and bring them to life.”

“I’ve been learning about and drawing dinosaurs since I was a kid,” explains Herschel Hoffmeyer, creator of the Apex Theropod Deck-Building Game, now on Kickstarter. “I even won a dinosaur art contest at a local library when I was very little. I was made to create these guys and bring them to life.”

Apex Theropod looks like a dinosaur-lover’s nocturnal emission…and Herschel himself might be the biggest dino-enthusiast you’ll ever meet. “I have National Geographic’s The Ultimate Dinopedia and the super-sized book Dinosaurs by David James. I really love what the indie company Lukewarm Media has done with their game Primal Carnage,” he gushes, adding as an afterthought that he hasn’t actually been able to play said game yet.

According to his Kickstarter bio, Herschel is an 8-year Army veteran and Game Art and Design student at the Arts Institute International in Kansas City. Intrigued about how his Army life segued into his current saurian pursuits, I contacted Herschel for an interview. “Apex started as a simple prototype dinosaur-themed game used for an assignment in one of my game design classes at the Arts Institute International of Kansas City,” he explained. “After seeing my game concepts compared to others, I knew I had a knack for game design. Shortly after, I worked on many different prototype games under the same dinosaur theme, game goals, and playable class ideas.”

“The dinosaur theme was definitely the theme from the beginning, just because I thought it would be really fun to play.” As for the mechanics, they were inspired by the Legendary: A Marvel Deck-Building Game, published by Upper Deck Entertainment. Like other deck-building games, Legendary starts each player with a small deck of relatively weak cards (in this case, S.H.I.E.L.D. agents). However, over the course of the game, they can use these cards to “recruit” more powerful, iconic Marvel heroes into their deck, and the winner will be the player who builds the cleverest deck in the shortest time. This evolution from humble beginnings is a potently addictive formula, which explains the explosion of popularity deck-builders have experienced since they were popularized by Donald X. Vaccarino’s Dominion in 2008. Herschel isn’t naive to the economics of the situation: one reason he selected the deck-building format is that, since the bulk of their contents are composed of duplicate cards, deck-builders are relatively inexpensive to manufacture.

This evolutionary gameplay is also the perfect complement to the theme of becoming the world’s top saurian predator. Herschel explains, “Most of the game’s mechanics are shaped around the theme, and three are really unique to the game. The first is the territory-based decks. With the environmental deck affecting those territories, that drives a sense of environment immersion. The second is that each player has a nest. The nest is separate from your playing deck and unique to whatever dinosaur you’re playing as. In the nest, you hatch cards that consist of just your dinosaur, and you also bring any prey hunted back to your nest to eat later. The third unique mechanic is the unforgiving boss battles. To dominate each territory, you have to fight off the other competing apex predator of that territory, and that is the boss. In a 5-player game, you have eight total bosses, and in a single-player game, you have three bosses and one ultimate boss.”

This evolutionary gameplay is also the perfect complement to the theme of becoming the world’s top saurian predator. Herschel explains, “Most of the game’s mechanics are shaped around the theme, and three are really unique to the game. The first is the territory-based decks. With the environmental deck affecting those territories, that drives a sense of environment immersion. The second is that each player has a nest. The nest is separate from your playing deck and unique to whatever dinosaur you’re playing as. In the nest, you hatch cards that consist of just your dinosaur, and you also bring any prey hunted back to your nest to eat later. The third unique mechanic is the unforgiving boss battles. To dominate each territory, you have to fight off the other competing apex predator of that territory, and that is the boss. In a 5-player game, you have eight total bosses, and in a single-player game, you have three bosses and one ultimate boss.”

Innovation by Carl Chudyk

Innovation

Innovation

by Carl Chudyk

Asmadi Games, 2010

$25 Buy from Amazon or Asmadi Games or try online at Isotropic

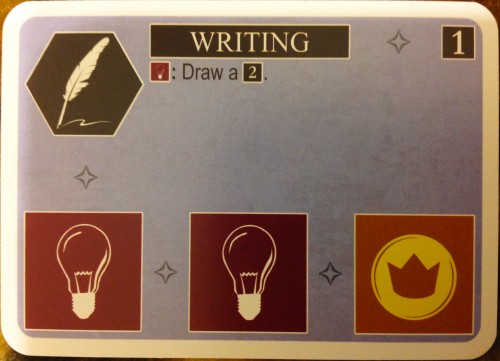

Writing [Blue/Age 1/Bulb]: Draw a 2.

It doesn’t look like much on its own, but that small amount of information tells you everything you need to know about one of the most monumental achievements in human history. It’s just one example of 105 concepts and technologies represented in Carl Chudyk’s clever (and occasionally revelatory) minimalistic card game Innovation.

Of course, being as it is an exploration of the march of human progress from Prehistory through the Information Age, Innovation is minimalistic only on its surface. The goal of the game, reduced to its simplest format, is to harness these advancing concepts to steer your culture (represented by a tableau of cards in front of you) toward monumental achievements—specifically, more and faster achievements than the other players. Ideas from The Wheel to The Internet are represented by the intersection, on a single card, of four very simple elements: a color (one of five, which might be thought of as the card’s suit); a value (the age, 1-10, that the invention hails from); a “dogma” effect, which can be called upon once the card has been “melded,” or put into play; and three icons, of one or more of 8 types, arranged around the bottom-left borders of the card like a supine L.

In play, the clipart-style icons and mostly solid colors make Innovation redolent of a child’s educational toy. From the outside, that is. In play—that is, to those actually experiencing the game—Innovation‘s minimalistic trappings hide a maximalistic struggle as epic as history itself.

Let’s take another look at Writing, for example. It’s an Age 1, or Prehistoric, technology. During setup, stacks representing all 10 Ages of history, each holding roughly 10 cards, are arranged in order. All players begin in Age 1, and can only begin drawing cards from the later ages once the Age 1 draw pile is depleted or if they have melded (added to their tableau) a technology from a later age. Since cards from later ages are almost universally more valuable than earlier ones, this makes that simple Writing technology, whose only effect is “Draw a 2”, the key to unlocking a host of strategic choices for the lucky player who draws it early in the game. While the other players are stuck in the Stone Age, discovering important but rudimentary technologies like Sailing, Pottery and Domestication, you can be drawing Age 2 (Classical era) technologies such as Mapmaking, Currency and Mathematics.

Let’s take another look at Writing, for example. It’s an Age 1, or Prehistoric, technology. During setup, stacks representing all 10 Ages of history, each holding roughly 10 cards, are arranged in order. All players begin in Age 1, and can only begin drawing cards from the later ages once the Age 1 draw pile is depleted or if they have melded (added to their tableau) a technology from a later age. Since cards from later ages are almost universally more valuable than earlier ones, this makes that simple Writing technology, whose only effect is “Draw a 2”, the key to unlocking a host of strategic choices for the lucky player who draws it early in the game. While the other players are stuck in the Stone Age, discovering important but rudimentary technologies like Sailing, Pottery and Domestication, you can be drawing Age 2 (Classical era) technologies such as Mapmaking, Currency and Mathematics.

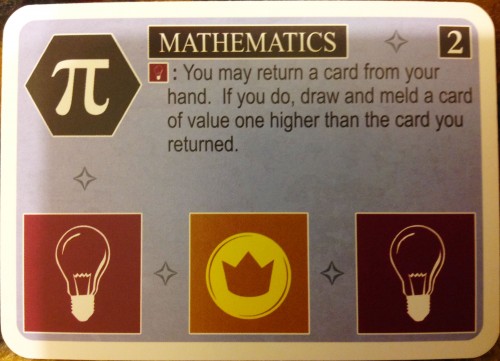

And once you have Mathematics in hand…oh, the places you’ll go then. Like Writing, Mathematics is a blue card with 2 bulb icons and 1 crown icon. Unlike Writing, it is an Age 2 technology, which means that as soon as it’s melded into your culture, you can draw from the Classical era’s suite of concepts even without Writing’s culture-advancing abilities. In fact, you couldn’t use Writing anymore if you wanted to; when you put Mathematic into play, you placed it on top of a stack of all other technologies of the same color you had previously discovered, burying them and making their dogma effect unusable. You could say that the advent of Mathematics pushed Writing out of the limelight. It’s still a part of your culture, but for now, its effects are dormant.

That doesn’t matter, though, because Mathematics’ dogma effect is even more powerful than Writing’s. It reads: “You may return a card from your hand. If you do, draw and meld a card of value one higher than the card you returned.” Again, this might not look like much at first. But let’s not forget the reason you melded Mathematics in the first place: you always get to draw from the age matching the highest-value card (determined by the card’s Age) in your culture. So you can use Mathematics to discard another Age 2 technology, like Monotheism (who needs religious mystery in the age of rationalism?) and replace it with something from Age 3 (the Medieval era)—say, Engineering. On your next turn, you can draw a new Medieval card, then immediately exchange it for something from Age 4, the Renaissance. And you can keep doing this to rocket through the ages, one turn at a time, discovering Banking and Refrigeration and Quantum Theory while your rivals are still puzzling out Road Building.

Tread cautiously, though. While early technologies are slow but stable, later technologies can be volatile. Even Writing, while it doesn’t provide the same rocket boost as Mathematics, has the advantage of being somewhat more contemplative and circumspect. With Mathematics, you must meld the card that you drew, even if it buries another technology you would rather have. Writing is slower, but it allows you to examine and judge for yourself exactly how and when to put your ideas into action.

February 17th, 2014 / 11:00 am

Little Inferno Review

Little Inferno

Little Inferno

Available on PC, Wii U, iOS, Android

Buy on Steam

The world is getting colder. Up past your chimney, the snow is coming down thick and fast. It’s been this way for years, but nobody seems to know, or really care, why. Whatever the reason, weather like this…it can’t possibly last forever. So why bother trying to figure it out?

Why bother going outside at all when you’ve got your very own Little Inferno Entertainment Fireplace, courtesy of Tomorrow Corporation? It’ll keep you warm and entertained forever, or as long as you’ve got stuff to burn, which is basically saying the same thing. Thanks to the many letters and catalogs that keep arriving mysteriously on your fireside mantel, it will be a long while before you run out of stuff to burn. Of course that, too, can’t possibly last forever. But why worry about the future, or the past, when you can live in an eternally incandescent present?

The aptly named Tomorrow Corporation is more than just a faceless, philanthropic corporate entity within the world of Little Inferno; it’s also the name of the independent game development studio made up of former World of Goo developers Kyle Gabler and Allan Blomquist, along with Henry Hatsworth‘s Kyle Gray. Combining elements of Seussian satire, Tim Burton-esque morbidity, and religious awe, Little Inferno (now available on multiple PC and mobile operating systems, as well as Wii U) delivers a harsh but winking upbraiding of the gaming industry, the wider entertainment, and industry as a whole; so harsh, in fact, that many critics at the time of its November 2012 release just couldn’t stomach it, finding the game unplayable and impossible to recommend. As the most important selling season of the year reaches its climax, however, and the various app stores flood with millions of Christmas and post-Christmas shoppers, this weird, cozy anti-game is worth revisiting—if nothing else, as a cautionary tale.

I call it an anti-game because, while there are moments of effervescent joy to be found in the playing, Little Inferno‘s best elements sit just outside the frame of its purposefully limited gameplay canvas, which tends closer to “toy” than “game.” To describe Little Inferno‘s design philosophy as “one note” would be to severely underrepresent its monocular POV and single-minded sense of purpose. In a rare example of truth in advertising, the Little Inferno Entertainment Fireplace does exactly and only what the packaging suggests. The player is offered only three ways of interacting with its cheerfully bleak world: click through Tomorrow Corporation’s various themed catalogs to send items to your mailbox, drag items out to stack them just so in the fireplace, and click anywhere within the fireplace to ignite that pile of old toys, correspondences, binding contracts or personal memories. And until its horizon-expanding conclusion, Little Inferno provides you only one view of the world, staring into the bright heart of the fire itself. As your neighbor, Sugar Plumps, writes, “I can stare into the fire forever, but not backwards… .”

Letters from Sugar Plumps and a few other key characters, including Miss Nancy, CEO of Tomorrow Corporation; and The Weatherman, “reporting from the Weather Balloon, over the smoke stacks, over the city,” form the core of Little Inferno‘s narrative—a narrative that seems at times absurd, at times ominous, but always serves to reinforce the critiques leveled by the game’s structure. Textual elements, such as the refrain of “it can’t last forever,” repeated references to a relentless, irreversible march forward (Sugar Plumps’s typography is idiosyncratic at best; the reason, as we find out later, is that her keyboard has lost its Delete key, so that “The possibilities go FORWARD forever! But can’t ever go back.”), and the forbiddingly cold weather (Sugar Plumps writes in another letter: “The city is fillllled with people! … I can see theeeir chimneys…and smell the smoooke! … But even though they are everywhere…they are far away like leeetle burning galaxies…with leeettle smoking chimneys on their heads! Ooooo it makes me cooold!”)—even if their meaning is not immediately clear, these all form the emotional backdrop for the player’s activities…which, as mentioned previously, revolve almost exclusively around burning things.

As any young pyro can attest, combustion is an exciting but brief event; like everything else in this game, it can’t last forever. And once you’ve burned something, it’s gone; you can’t ever go backwards. This element made Little Inferno a difficult game for critics to review. On the one hand, all burnable objects react in often surprising and always entertaining ways. Heavenly bodies (in miniature, naturally) exert a very localized gravity that causes other objects to orbit around them; “Kitty Kitty Poo Poo” releases massive quantities of fast-burning cat excrement; mysterious wooden idols sing in three-part harmony; and a floppy disc containing the Little Inferno beta causes the fire effects to briefly tranform into blocky, low-resolution pixels. Combining these objects in different ways can cause chain reactions and emergent situations, increasing the entertainment value further.

As any young pyro can attest, combustion is an exciting but brief event; like everything else in this game, it can’t last forever. And once you’ve burned something, it’s gone; you can’t ever go backwards. This element made Little Inferno a difficult game for critics to review. On the one hand, all burnable objects react in often surprising and always entertaining ways. Heavenly bodies (in miniature, naturally) exert a very localized gravity that causes other objects to orbit around them; “Kitty Kitty Poo Poo” releases massive quantities of fast-burning cat excrement; mysterious wooden idols sing in three-part harmony; and a floppy disc containing the Little Inferno beta causes the fire effects to briefly tranform into blocky, low-resolution pixels. Combining these objects in different ways can cause chain reactions and emergent situations, increasing the entertainment value further.

December 23rd, 2013 / 11:05 am

CENTERPIECE by Daniel S. Muehlmeier

CENTERPIECE

CENTERPIECE

by Daniel Muehlmeier/Lee Mothes

Warm Wax Inc., 1991

2 players / 30 minutes / $19.99 from eBay

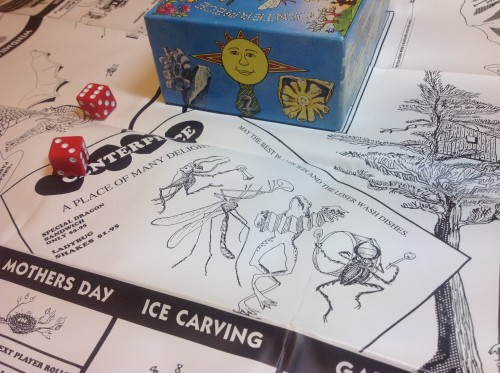

CENTERPIECE is a board game designed by Daniel S. Muehlmeier, self-described “unlocker of secrets,” with art by Lee Mothes. It was taken off a Goa’uld mother ship.

You won’t find CENTERPIECE in the Toys & Games section of your local Barnes & Noble. The game, originally published in 1991, is a notoriously tough sell. “I do well in the twenty-dollar range,” said the author in his recent Kickstarter campaign, which managed to raise only $615 of funds from 23 backers. “I keep a few game boxes in my cars back-window. Creating sales proved tough for me.”

“One restaurant placed five games. Near where people pay. All five disappeared, I never even restock them. Example of really bad-marketing skills. Yet I’m really looking forward, to direct mail to customers.” Following the close of the Kickstarter, the game is now being listed on eBay under the heading “tradition game, toys and Hobbies.” Yet this is just a stepping stone for Muehlmeier, who would eventually like to see his game displayed in a contemporary art museum.

Nor is this a delusionary ambition. Bad-marketing skills aside, Muehlmeier’s creation intrigues; in fact, it’s best approached from the vantage point of art (as opposed to game) criticism. Even taken as a game, CENTERPIECE is an answering shot to the pet theory that the whole of a game’s value rests within its mechanical core, for which the superficial elements of theme and appearance serve as mere window dressing.

CENTERPIECE‘s mechanisms of play are invitingly familiar. In fact, CENTERPIECE could accurately be called a pastiche of several games known to all American children: Monopoly, Parcheesi, Chutes and Ladders. Pastiche in both senses of the word, since CENTERPIECE‘s core mechanisms walk a tricky line between quotidian simplicity and schizophrenic montage, made no more easily reconciled by the often indecipherable rules, which read like an antique riddle. “Players are encouraged to use common sense,” the single-leaf rules advise. “For example, if both players are sent to the Bird Cage; because a player rolled a two, while visiting the Honey Jar space. The player who rolled snake-eyes would roll for doubles first. Both player would stay for three turns, unless doubles were rolled.”

Once mastered, CENTERPIECE is an almost fully luck-driven affair, a roll-and-move game destined to be despised by the modern board game community, who have become spoiled by worker placement, economic engines, asymmetric player roles, and all the other innovations the last two decades have brought to the medium (remember, CENTERPIECE is a time capsule from the early ’90s, although aesthetically, it hearkens to an even earlier era). Yet the game’s “superficial” elements are not to be discounted, for they create a metaphorical frame or structure as the game plays out, turning a simple reimagining of Monopoly into something that far exceeds the sum of its parts.

As if to embody this very statement, the first bread crumb along CENTERPIECE‘s allegorical trail is the fact that the game’s box, colorfully illustrated by artist Lee Mothes, is also central—both literally and figuratively—to its gameplay. Once the board has been unfolded, the box top is placed at its center, a mechanically unimportant gesture that receives special emphasis in the game rules—and is hammered home with every turn, as the dice pounding off of its cardboard surface speak testimony to its substance (that the dice must be rolled off of the box top is another apparently superficial but ritualistically significant gesture). As the eponymous centerpiece, this raised rectangle of cardboard naturally draws the eye—it is the only spot of color in an otherwise black-and-white composition—while hiding the game’s deepest secrets. A display of puzzle pieces nestled beneath track the players’ scores, and it is to Muehlmeier’s infinite credit that he keeps this indispensible information hidden away until the moment that the box is lifted, a moment that always coincides with a change in the data under scrutiny. It is the uncertainty principle actualized.

December 4th, 2013 / 12:00 pm

Mass Effect and The Self-Imposed Strictures of Interactive Storytelling

In an era of broad canonical redefinition, when more and more previously marginalized forms, from comic books to slash fiction, are receiving the literary attention they have always deserved, one storytelling medium remains stubbornly difficult for anyone, even its devotees, to take too seriously. That medium is gaming, and I’m afraid that it’s all my fault.

I am a gamer. I have, admittedly, much more passion reserved for gaming’s potential, its Platonic ideal, than for any of its present, more or less imperfect incarnations. Sadly, my attitude toward such an ideal waxes cynical of late. Ten years ago, electronic gaming was just starting to emerge from its reflex-test swaddling clothes and make faltering baby steps in a dozen directions exciting new directions, each a distant promise of something previously unseen in the world of art and literature. Today, the bloated man-child of mainstream gaming has all but sunk into a quagmire of the same stories repeated like a tattoo, with more flash and less substance as each year passes, as the intersection of “game” and “story” becomes increasingly cemented in a model that leaves little room for the kind of progressive storytelling originally promised. Its syntax, the language of player interaction in which its message is couched, has become lazy and predictable. The once promising child’s development may be permanently arrested, and I, as a gamer, am to blame.

In a McCluhanian nod, that syntax, rather than the literal story being told, is the true carrier of gaming’s message. It’s the push-pull between the intentionality of the game designer, as expressed in the structure (digital or physical) presented to the player as “game,” and the player’s own investment and empowerment within the narrative. It is, in many ways, a revival of the call-and-response communal storytelling of folklore and early theater, except that, in a gleefully postmodern twist, the storyteller hopped a jet out of town months before the audience even arrived. The “story” is the sealed and packaged structure left behind, its white spaces carefully measured, the player’s responses anticipated and, in many cases, artfully curtailed. The syntax encompasses both the (always limited) means by which the player is allowed to respond to the piece—say, by rotating the camera, jumping, pulling levers, pushing boxes, et cetera—and the degree to which the storyteller has correctly anticipated, and provided appropriate responses to, the player’s interactions. Games that employ the same syntax cannot help but deliver the same message, over and over, no matter what the “story” appears to be on the surface.

Critically, the syntax is always imperfect (otherwise, the game would be a perfect simulation of real life, which would negate the game designer’s authorial intentionality and, in any case, be unplayably boring). A great deal of gaming’s storytelling potential lies in the allowed-but-unanticipated interactions, the frontier spaces wherein the player becomes more than a marionette acting out canned responses and takes on a more active, improvisational role. Not that this always occurs within the game itself.

Theoretically, games could be as broad in their form and intention as the written word. However, the vast majority of mainstream games occupy a stiflingly narrow syntactical space, forcing the player to repeat the same deeply worn gestures ad infinitum. First- and third-person shooting games—often, the only difference is whether the protagonist’s legs are visible—dominate the home console market, with action-adventure titles in the style of Devil May Cry and God of War picking up most of the slack. On computers, the preferences differ, but the tropes are no less ingrained. With 90%-plus of a game’s syntax devoted to the art of war, you can imagine the narrative range allowed.

The gating factors of syntax aside, there is a deeper problem preventing mainstream gaming from establishing itself firmly in the realm of serious storytelling: the interests of gamers, even those who look toward the horizon, are simply counterproductive to good storytelling. Put another way, people don’t play games, even story-driven games, with the same expectations and motivations as they would read a book. Gaming attracts and rewards certain personality types and behaviors; in fact, it trains those behaviors, in a Pavlovian sense. Gamer’s want to win, they want to win completely, and the act of playing the game reinforces those desires and expectations.

When I play games, I want to talk to, collect, and do everything that the game allows. I am not a competitive person; rather, I’m driven by a desire to fully appreciate the game’s construction. If there are multiple endings, branching options, I want to see them all, and I want to see my time and effort rewarded. The problem is, these desires just don’t make for very interesting or effective stories; I am incapable of acting in my own best interests in this regard. Even those games that attempt to push the envelope ultimately have to succumb to the gamer’s demands, or they will not get played.

And worse, as a gamer, I do not actually want what I think I want. For the past decade, video game publishers have consistently pushed choice-driven storytelling as a key feature in their major releases, and it is clear from consumer response that this is something most gamers think they desire. From Fable to The Walking Dead, Deus Ex to Dishonored, the message is clear: gamers desperately want a part in the story being told; they want to feel as though their interactions matter.

EA and Bioware’s Mass Effect series lives up to this promise better than most. From the first release of this space epic trilogy in 2007, the series has placed an emphasis, almost to excess, on player-defined storytelling that is both novelistic in its scope and cinematic in its execution. The series offers a roughly even split between kinetic over-the-shoulder shooting and loquacious story content, during which the player is bombarded by constant dialogue choices utilizing a “conversation wheel,” via which players can select the tack, though not the actual content, of their in-game avatar Commander Shepard’s responses.