Easy To Get Here, Hard to Leave

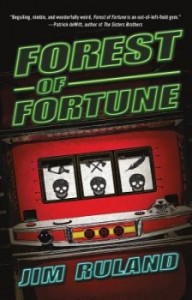

Forest of Fortune

Forest of Fortune

by Jim Ruland

Tyrus Books, July 2014

288 pages / $24.99 Buy from Amazon

In his 1998 documentary Advertising and the End of the World, Sut Jhally defines culture as the stories we tell ourselves about ourselves. He further points out that the primary storytellers in our culture—the ones who have the most prominent voice in articulating our value and belief systems—are advertisers. It’s an elegant point, so seemingly simple that its depth can be lost without a few moments to meditate on it.

Most discussions of advertising itself in our culture are limited to the question, “Did that particular advertisement inspire me to purchase that particular commodity?” It’s a feckless question. Jhally notes that the answer to it may be relevant for the people selling the commodity, but it has little relevance to everyone else. Instead, we should be asking ourselves, “What’s the deep-seeded impact of the overwhelming wave of advertising that crashes on us every day?”

What we, as readers and/or writers of novels, don’t discuss much is the relationship of our medium to advertising. Novels are the one contemporary media that is not and can not be saturated with ads. (At least that’s true for the paper ones.) This is one of the reasons I read so many novels. This also leads to one of the great challenges for novelists: to wedge their little story into a culture besieged by several thousand daily advertisements.

Jim Ruland’s recent novel Forest of Fortune is one of those little stories consciously wedging itself into the conversation about advertising. It treads upon similar ground as Jhally’s documentary, yet does so in a tone that allows the reader a bit more freedom in her interpretations. Jhally’s tone is clear from it’s very title: Advertising and the End of the World. Nothing spells doom like that. Ruland also demonstrates his approach early, but in a much more subtle fashion. One of his protagonists, Pemberton, checks into a rundown motel with weekly and monthly rates below the forty-dollar nightly rate. The clerk gives him a sales pitch about one of the rooms. Pemberton is hyper-aware of what’s going on. “A copywriter by trade, [he] knew brochure copy when he heard it, yet was seduced all the same.”

Again, it’s a simple, elegant way of introducing a deep point. Pemberton’s reaction matches a very common one in our culture. We’re often seduced by advertising, untroubled by the knowledge that we’re being lied to, uncritical of the alternate reality it sells. We want the story regardless. In almost every case, it’s the story we purchase. The commodity is just the bi-product, something we’ll keep around until the story loses its luster.

The setting of novel further illustrates this relationship with advertising and consumer commodity culture. It takes place in a fictional California town called Falls City. The name is probably more literary play then heavy handed symbolism. Pemberton arrives there and thinks, “False City, indeed.” It’s a fun way of sending a reader away from the falsity promised by the more specific setting of the novel, Falls City’s Thunderclap Casino.

August 25th, 2014 / 10:00 am